A Comprehensive Guide to Validating CRISPR Edits: From Sanger to NGS Sequencing Methods

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a definitive guide to validating CRISPR-Cas9 gene edits.

A Comprehensive Guide to Validating CRISPR Edits: From Sanger to NGS Sequencing Methods

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a definitive guide to validating CRISPR-Cas9 gene edits. It covers the critical transition from basic DNA analysis to advanced RNA-seq, detailing robust sequencing methodologies for confirming on-target efficiency, detecting unintended transcriptomic changes, and troubleshooting low knockout efficiency. The content synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends, including the role of AI and clinical validation frameworks, to ensure reliable and comprehensive analysis of gene editing outcomes for both research and therapeutic applications.

Why DNA Sequencing Alone is Not Enough: The Critical Need for Comprehensive CRISPR Validation

While PCR amplification followed by Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for confirming targeted CRISPR edits due to its accuracy and low cost, this method faces significant limitations in scalability, sensitivity, and ability to detect complex modifications. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of PCR+Sanger against emerging sequencing technologies for CRISPR validation. We present quantitative data demonstrating how next-generation sequencing (NGS) and specialized computational tools are overcoming these limitations, enabling researchers to comprehensively assess editing efficiency, detect off-target effects, and characterize complex editing outcomes with unprecedented resolution.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, providing an easily programmable platform for precise genome editing. However, accurately validating these edits remains a critical bottleneck in the research pipeline. For years, PCR amplification coupled with Sanger sequencing has served as the primary validation method, offering a seemingly straightforward approach to confirm intended edits. This method involves amplifying the target region via PCR and subsequently determining its nucleotide sequence through Sanger's chain-termination method.

Despite being considered the gold standard for detecting single nucleotide variants and small insertions/deletions, this approach faces inherent technological constraints. As research progresses toward more complex editing strategies—including multiplex editing, large knock-ins, and therapeutic applications—the limitations of PCR+Sanger become increasingly problematic. This guide examines these limitations through experimental data and presents viable alternatives for comprehensive CRISPR validation.

Experimental Comparison of CRISPR Validation Methods

Methodologies and Protocols

PCR + Sanger Sequencing Protocol The standard protocol for validating CRISPR edits begins with PCR amplification of the target region from purified genomic DNA, followed by Sanger sequencing. Critical steps include:

- DNA Extraction: Purify genomic DNA from edited cells or tissues.

- Target Amplification: Design locus-specific primers flanking the edit site (typically generating 500-1000 bp amplicons).

- PCR Purification: Clean amplified products to remove primers and enzymes.

- Sanger Sequencing: Prepare sequencing reaction with fluorescent dye-terminators.

- Capillary Electrophoresis: Separate termination products by size.

- Data Analysis: Interpret chromatograms for sequence variants [1] [2].

NGS-Based Validation Protocol Next-generation sequencing provides a comprehensive alternative:

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA and ligate with platform-specific adapters.

- Target Enrichment: Use hybridization baits or PCR to enrich for target regions.

- Cluster Amplification: Bridge amplify fragments on flow cell (Illumina).

- Sequencing by Synthesis: Parallel sequencing with fluorescent nucleotides.

- Data Analysis: Map reads to reference genome, call variants [1] [3].

High-Throughput Genotyping Protocol Specialized NGS approaches like genoTYPER-NEXT offer optimized workflows:

- Direct Submission: Submit CRISPR-edited cells in multiwell plates.

- Cell Lysis & Barcoding: Lyse cells and amplify with barcoded primers.

- Pooled Sequencing: Multiplex thousands of samples on Illumina platforms.

- Interactive Analysis: Visualize results via dedicated browser [3].

Performance Comparison Across Key Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of CRISPR validation methods across critical performance metrics

| Metric | PCR + Sanger | T7 Endonuclease Assay | NGS (Amplicon) | High-Throughput Genotyping |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | ~15-20% allele frequency [4] | ~5% [4] | <1% allele frequency [3] | <1% allele frequency [3] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | 1 target per reaction [1] | 1 target per reaction | 1 to >10,000 targets [1] | Up to 10,000 samples per run [3] |

| Edit Characterization | Limited to predominant variants [4] | Indel frequency only [4] | Full sequence resolution | Full INDEL resolution, frameshift analysis [3] |

| Quantitative Capability | Not quantitative [1] | Semi-quantitative | Quantitative [1] | Quantitative with allele frequency [3] |

| Turnaround Time | ~8 hours sequencing + analysis [1] | ~3-4 hours | Days (library prep + sequencing) [1] | Varies with scale |

| Cost Per Sample | $ (Low) [1] | $ (Low) | $$ to $$$$ (Medium-High) [1] | Varies with scale |

Table 2: Accuracy assessment of computational tools for analyzing Sanger sequencing data of CRISPR edits (based on artificial templates with predetermined indels) [4]

| Tool | Simple Indels (1-3 bp) | Complex Indels | Knock-in Sequences | Indel Sequence Deconvolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIDE | Good accuracy | Variable estimation | Limited capability | Limited |

| ICE | Good accuracy | Variable estimation | Limited capability | Moderate |

| DECODR | Best overall accuracy | Most accurate for complex indels | Limited capability | Best among tools |

| SeqScreener | Good accuracy | Variable estimation | Limited capability | Moderate |

| TIDER | Not specialized for knock-ins | Not specialized for knock-ins | Best for knock-in efficiency | Specialized for HDR events |

Limitations of PCR and Sanger Sequencing in CRISPR Validation

Limited Sensitivity and Inability to Detect Mosaicism

PCR+Sanger sequencing requires a homogeneous template for clear interpretation, limiting its ability to detect mosaic populations where editing efficiency is below 15-20% [2] [4]. The method struggles to resolve complex mixtures of editing outcomes, as evidenced by chromatograms becoming indecipherable with overlapping traces when analyzing amplicons from heterogeneous samples [1]. This poses significant challenges in detecting off-target effects, which typically occur at low frequencies across the genome.

Lack of Quantitative Capability

Unlike qPCR or NGS, Sanger sequencing provides no quantitative information about editing efficiency or allele frequency [1]. While computational tools like TIDE and ICE can estimate indel frequencies from trace files, their accuracy varies considerably, particularly with complex indels or extreme (low or high) editing efficiencies [4]. This limitation prevents accurate assessment of editing efficiency in polyclonal populations.

Low Scalability and Throughput

Sanger sequencing is fundamentally low-throughput, limited to analyzing one target per reaction without multiplexing capability [1]. This creates a significant bottleneck in large-scale projects requiring analysis of multiple targets or samples. As CRISPR applications expand to genome-wide screens and therapeutic development, this scalability limitation becomes increasingly prohibitive.

Inability to Resolve Complex Editing Outcomes

While Sanger excels at confirming specific intended edits, it provides limited resolution of diverse editing outcomes within a population. In studies comparing computational tools, the ability to deconvolute complex indel sequences varied significantly, with most tools struggling to accurately characterize more complicated indel patterns [4]. This is particularly problematic for CRISPR applications where heterogeneous editing outcomes are common.

Restricted Sequence Context

Sanger sequencing read lengths typically max out at approximately 500-1000 base pairs per reaction [1] [2], limiting the genomic context that can be assessed in a single assay. This constraint hinders comprehensive analysis of large knock-ins, deletions, or rearrangements that may result from CRISPR editing. Furthermore, the technology cannot reliably detect structural variations or complex rearrangements that may occur at off-target sites.

Advanced Solutions for Comprehensive CRISPR Validation

Next-Generation Sequencing Approaches

Targeted NGS methods address nearly all limitations of Sanger sequencing by providing:

- Ultra-sensitive detection of low-frequency edits (<1% allele frequency) [3]

- Multiplexed analysis of thousands of targets or samples simultaneously [1] [3]

- Complete sequence resolution of all editing outcomes in a population [3]

- Quantitative measurement of allele frequencies [1]

These approaches enable researchers to simultaneously assess on-target efficiency, characterize editing profiles, and detect off-target effects in a single assay. While NGS has higher per-sample costs and longer turnaround times, its comprehensive data output often makes it more cost-effective for large-scale studies [1].

Computational Tools for Enhanced Sanger Data

Specialized algorithms can extend the utility of Sanger data for CRISPR validation:

- TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition): Estimates editing efficiency and indel distribution by decomposing Sanger trace data [5] [4]

- TIDER (Tracking of Insertions, Deletions, and Recombination events): Specialized for analyzing homology-directed repair events and small edits using an additional donor sequencing trace [5]

- DECODR (Deconvolution of Complex DNA Repair): Shows superior performance for complex indel patterns according to comparative studies [4]

- ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits): Provides reliable estimation of editing efficiency for simple indels [4]

These tools enable more quantitative analysis from Sanger data but still face limitations with highly complex editing outcomes.

Integrated Workflows for Comprehensive Validation

Leading laboratories are adopting tiered validation strategies that combine multiple methods:

- Rapid screening using T7E1 or similar mismatch detection assays

- Initial confirmation of editing with PCR+Sanger and computational analysis

- Comprehensive characterization using targeted NGS for off-target assessment and precise quantification

This integrated approach balances speed, cost, and comprehensiveness while addressing the limitations of any single method.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for CRISPR validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Providers |

|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Chain-termination sequencing with fluorescent detection | BigDye Terminator kits (Thermo Fisher) [2] |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries for high-throughput platforms | Illumina Nextera, Swift Biosciences Accel-NGS [1] |

| Computational Analysis Tools | Deconvolute complex editing outcomes from sequencing data | TIDE, ICE, DECODR, CRISPResso [5] [4] |

| High-Throughput Genotyping Services | Large-scale validation of edited cell lines | genoTYPER-NEXT [3] |

| Digital PCR Systems | Absolute quantification of editing efficiency | Bio-Rad QX200, Thermo Fisher QuantStudio [1] |

| CRISPR Validation Panels | Targeted sequencing for on- and off-target assessment | Custom hybridization panels (Illumina, Agilent) |

The limitations of PCR and Sanger sequencing in characterizing CRISPR edits beyond the immediate target site are becoming increasingly apparent as applications advance toward therapeutic development. While Sanger remains valuable for confirming specific intended edits in small-scale studies, its inability to quantitatively assess complex editing outcomes and off-target effects necessitates complementary approaches.

Next-generation sequencing technologies provide the comprehensive profiling capability required for rigorous therapeutic development, enabling sensitive detection of off-target effects and complete characterization of editing outcomes. As the field progresses, integrated validation workflows that combine the cost-effectiveness of Sanger for initial screening with the comprehensiveness of NGS for final characterization will become standard practice.

Future advancements in long-read sequencing, single-cell technologies, and computational analysis will further enhance our ability to fully characterize CRISPR editing outcomes, ultimately supporting the safe and effective translation of CRISPR-based therapies into clinical applications.

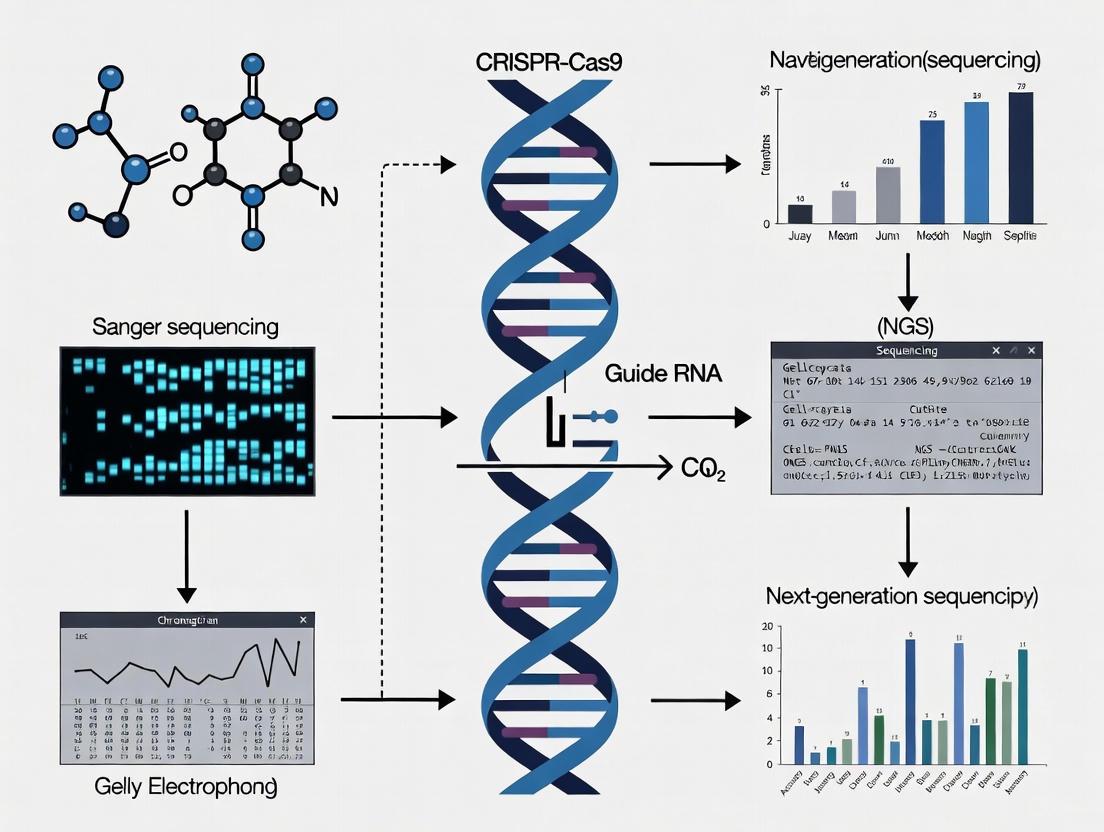

Methodological Diagrams

CRISPR-based genome editing technologies have revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development by enabling precise, programmable modification of the genome [6]. However, traditional validation methods focusing solely on DNA-level analysis provide an incomplete picture of editing outcomes. Emerging research demonstrates that RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) reveals a hidden landscape of transcriptional changes that remain undetectable through conventional PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of target DNA sites [7] [8]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates RNA-seq against established CRISPR analysis methods, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data to inform their validation strategies.

The Limitations of Traditional CRISPR Validation Methods

Standard approaches for validating CRISPR edits typically examine only the immediate target site, potentially missing substantial unintended consequences. DNA-based methods can confirm intended mutations but fail to detect transcriptome-wide alterations that significantly impact gene function and cellular phenotype [7].

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Validation Methods

| Method | Detection Capability | Unanticipated Change Detection | Throughput | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | Target site mutations | Limited | Low | Low |

| T7E1 Assay | Editing efficiency (indels) | None | Medium | Low |

| TIDE Analysis | Indel spectrum | Limited | Medium | Low-medium |

| ICE Analysis | Indel spectrum and efficiency | Moderate (large indels) | Medium | Low-medium |

| RNA-seq | Transcriptome-wide changes | Comprehensive | High | Medium-high |

Traditional DNA-focused methods like T7E1, TIDE, and ICE provide valuable data on editing efficiency and small indels at the target site [9]. However, these approaches cannot detect the full spectrum of transcriptional alterations occurring beyond the immediate target locus, creating significant blind spots in validation protocols [7].

RNA-Seq Reveals the Hidden Transcriptional Impact of CRISPR

RNA-seq provides a comprehensive view of CRISPR-induced changes by capturing the entire transcriptional landscape rather than just target DNA sequences. This approach has uncovered numerous unexpected consequences of genome editing that would otherwise remain undetected [7] [8].

Documented Unanticipated Changes Detected by RNA-Seq

Analysis of RNA-seq data from multiple CRISPR knockout experiments has revealed several categories of unintended transcriptional alterations:

- Inter-chromosomal fusion events: Chimeric transcripts connecting genes from different chromosomes

- Exon skipping: Complete exclusion of exons from mature transcripts

- Chromosomal truncation: Large-scale deletion of chromosomal segments

- Neighboring gene alterations: Unintentional transcriptional modification and amplification of genes adjacent to the target site [7]

These findings highlight a critical limitation of DNA-focused validation methods. As one study concluded, "The inadvertent modifications identified by the evaluation of 4 CRISPR experiments highlight the value of using RNA-seq to identify transcriptional changes to cells altered by CRISPR, many of which cannot be recognized by evaluating DNA alone" [8].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies in CRISPR Validation

NF1 and SUZ12 Knockout Experiments

In CRISPR knockout experiments targeting Neurofibromin 1 (NF1) and SUZ12 in immortalized human Schwann cells, researchers employed Trinity software for de novo transcript assembly from RNA-seq data [7]. This approach identified numerous changes at the transcript level that escaped detection by standard DNA amplification methods, including:

- Small indels that avoided nonsense-mediated decay

- Alternative splicing events

- Potentially functional N-terminal truncated proteins resulting from alternative start codon usage [7]

SRGAP2 Multi-Copy Gene Knockout

When targeting multiple copies of SLIT-ROBO Rho GTPase Activating Protein 2 (SRGAP2) in human osteosarcoma cells, researchers discovered that RNA-seq analysis provided crucial information about the knockout completeness across all gene copies [7]. Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blotting complemented RNA-seq findings, demonstrating how multi-modal validation strengthens experimental conclusions.

Comparative Experimental Protocols

RNA-Seq Workflow for CRISPR Validation

Diagram 1: RNA-seq CRISPR validation workflow (6 words)

Trinity-Based Analysis for Novel Transcript Discovery

For detecting unanticipated transcriptional changes, the Trinity platform enables de novo transcript assembly without a reference genome [7]. This method proves particularly valuable for identifying:

- Novel fusion transcripts

- Alternative splicing variants

- Previously unannotated transcripts arising from CRISPR editing

- Chimeric RNA species resulting from inter-chromosomal rearrangements [7]

The protocol involves:

- Isolating RNA from CRISPR-treated and control cells

- Preparing sequencing libraries with sufficient depth for transcript characterization

- Running Trinity assembly on processed reads

- Comparing assembled transcripts between experimental conditions

- Validating unexpected findings through orthogonal methods

Advanced CRISPR Validation Technologies

CRISPRgenee: Enhanced Loss-of-Function Screening

A recent innovation called CRISPRgenee addresses limitations in conventional CRISPR knockout and interference systems by combining simultaneous gene knockout and epigenetic repression [10]. This dual-action system demonstrates:

- Improved depletion efficiency over individual CRISPRi or CRISPRko

- Reduced sgRNA performance variance

- Accelerated gene depletion kinetics

- Enhanced consistency in phenotypic effects [10]

Single-Cell CRISPRclean (scCLEAN)

The scCLEAN method utilizes CRISPR/Cas9 to selectively remove highly abundant transcripts from single-cell RNA-seq libraries, redistributing sequencing reads toward less abundant transcripts [11]. This approach:

- Targets the top 1% of the transcriptome while redistributing approximately half of reads

- Enhances detection of low-abundance biologically relevant transcripts

- Improves signal-to-noise ratio in single-cell experiments

- Uncovered inflammatory signatures in coronary artery cells relevant to disease pathogenesis [11]

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data Analysis

Table 2: Detection Capabilities of CRISPR Validation Methods for Various Alterations

| Type of Change | DNA Methods | RNA-seq | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small indels | Yes | Yes | Confirmed by both methods [7] |

| Large deletions | Limited | Yes | RNA-seq detected chromosomal truncation [7] |

| Exon skipping | No | Yes | Identified in multiple experiments [7] |

| Fusion transcripts | No | Yes | Inter-chromosomal fusions detected [7] |

| Neighboring gene effects | No | Yes | Unintentional modification of adjacent genes [7] |

| Alternative splicing | No | Yes | Multiple splicing alterations identified [7] |

| Expression changes | No | Yes | Genome-wide differential expression [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Validation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Trinity software | De novo transcript assembly | Identifies novel transcripts and fusion events [7] |

| Synthego ICE | Indel characterization from Sanger data | Provides NGS-comparable results without high cost [9] |

| scCLEAN reagents | Abundant transcript removal | Enhances detection of low-abundance transcripts in scRNA-seq [11] |

| CRISPRgenee system | Dual knockout and repression | Improves loss-of-function efficacy and reproducibility [10] |

| OptiType v1.3.5 | Cell line authentication | Confirms sample identity through HLA typing [7] |

| 10X Genomics platform | Single-cell RNA sequencing | Enables cellular heterogeneity analysis post-editing [11] |

| N1-Methoxymethyl picrinine | N1-Methoxymethyl picrinine, MF:C22H26N2O4, MW:382.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Phenoxy-1-phenylethanol-d2 | 2-Phenoxy-1-phenylethanol-d2, MF:C14H14O2, MW:216.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence demonstrates that RNA-seq provides an essential dimension in CRISPR validation by revealing transcriptomic changes inaccessible to DNA-focused methods. While traditional techniques retain value for assessing target site editing efficiency, comprehensive validation requires transcriptome-wide analysis to detect unintended consequences. The integration of RNA-seq into standard CRISPR validation pipelines represents a critical advancement for basic research and therapeutic development, ensuring a complete understanding of editing outcomes and their functional implications. As CRISPR technologies continue evolving toward clinical applications, robust validation methodologies incorporating transcriptomic analysis will be essential for establishing safety and efficacy.

While CRISPR-based genome editing has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development, the full spectrum of unintended structural consequences at the target site often goes undetected by conventional genotyping methods. Standard validation approaches relying on PCR amplification of the immediate target region followed by Sanger sequencing provide limited information, failing to reveal complex rearrangements and transcript-level alterations that can compromise experimental results and therapeutic safety [7] [8]. Advanced sequencing methodologies, particularly RNA-sequencing and specialized DNA-sequencing approaches, have uncovered a troubling prevalence of unintended on-target effects that escape conventional detection.

The most significant unintended effects include large deletions, exon skipping, and fusion transcripts – structural alterations that can disrupt gene function, create aberrant proteins, or eliminate therapeutic efficacy. These artifacts demonstrate that successful CRISPR editing requires moving beyond simple indel characterization to comprehensive structural analysis. This guide compares the detection capabilities of various sequencing methods for identifying these critical unintended effects, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to enhance their CRISPR validation strategies.

Comparative Detection Capabilities of Sequencing Methods

Table 1: Detection Capabilities of Sequencing Methods for CRISPR Artifacts

| Sequencing Method | Large Deletions | Exon Skipping | Fusion Transcripts | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | Limited to small indels near cut site | Undetectable | Undetectable | Limited by PCR primer placement; misses structural variants |

| Short-Read RNA-seq | Inferred from transcript absence | Detectable | Detectable if breakpoint within sequenced fragment | Cannot span complex rearrangements; alignment challenges in repetitive regions |

| Long-Read RNA-seq | Direct detection of large structural variants | Direct detection with full transcript context | Direct detection with phasing information | Higher cost; lower throughput; specialized expertise required |

| CRAFTseq (Multi-omic) | Targeted DNA sequencing with transcriptome correlation | Detectable via transcriptome | Detectable via transcriptome | Plate-based, lower throughput; requires customized design |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Unintended Effect Frequencies in CRISPR Experiments

| Study System | Target Gene | Large Deletions Detected | Exon Skipping Frequency | Fusion Transcripts | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSC1λ Schwann Cells [7] | NF1 | Chromosomal truncation identified | Confirmed in multiple clones | Inter-chromosomal fusion event | RNA-seq with Trinity assembly |

| 143B Osteosarcoma [7] | SRGAP2 | Large deletions confirmed | Not reported | Unintentional transcriptional modification of neighboring gene | RNA-seq, ddPCR, Sanger sequencing |

| SKOV3 Ovarian [7] | STAT3 | Not specifically reported | Identified in CRISPR clones | Not reported | RNA-seq analysis |

| Primary Human Cells [12] | Multiple loci | Not quantified | Not quantified | Not quantified | CRAFTseq (targeted DNA + transcriptome) |

Detailed Characterization of Key Unintended Effects

Large Deletions

Experimental Evidence: Analysis of CRISPR knockout experiments in HSC1λ human Schwann cells targeting the NF1 gene revealed a chromosomal truncation that was not detectable through standard PCR amplification of the DNA around the CRISPR target site [7]. This finding demonstrates that the cellular repair processes following CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks can generate substantially larger genomic rearrangements than typically assayed. Similarly, in the 143B osteosarcoma cell line targeting SRGAP2, large deletions were confirmed through RNA-sequencing analysis, highlighting that DNA-level assessments alone provide an incomplete picture of editing outcomes [7].

Detection Methodology: The most effective approach for identifying large deletions involves long-range PCR followed by sequencing, which can capture deletions spanning thousands of bases. However, RNA-sequencing provides complementary evidence through the identification of transcriptional consequences, such as the complete absence of exons or altered expression of neighboring genes. For the SRGAP2 experiment, researchers employed droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) to precisely quantify copy number variations resulting from large deletions, providing absolute quantification of deletion frequencies [7].

Exon Skipping

Experimental Evidence: CRISPR-mediated editing can disrupt splicing patterns, leading to the exclusion of entire exons from mature transcripts. In the NF1 knockout experiment, RNA-seq analysis identified exon skipping events that would not be apparent from DNA-based genotyping [7]. This phenomenon has been particularly documented when CRISPR cuts occur near exon-intron boundaries, potentially disrupting splicing regulatory elements or creating new cryptic splice sites.

Detection Methodology: Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data using tools like Trinity enables comprehensive characterization of splicing variants [7]. This approach reconstructs transcript isoforms without reference genome bias, allowing identification of novel splicing patterns induced by CRISPR editing. For the NF1 model, this analysis confirmed the success of CRISPR modifications while simultaneously identifying unexpected transcriptional consequences that would affect functional interpretation.

Fusion Transcripts

Experimental Evidence: One of the most striking findings from RNA-seq validation of CRISPR edits is the formation of inter-chromosomal fusion events. In the NF1 knockout experiment, researchers identified an inter-chromosomal fusion that joined sequences from different chromosomes, creating a novel chimeric transcript [7]. Additionally, in the SRGAP2 model, CRISPR editing led to unintentional transcriptional modification and amplification of a neighboring gene, demonstrating how on-target editing can have cis-regulatory consequences extending beyond the immediate target locus [7].

Detection Methodology: De novo transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data is particularly powerful for identifying fusion transcripts, as it does not rely on existing transcript models and can reconstruct novel chimeric sequences. In the analyzed experiments, this approach successfully identified fusion events that connected the targeted gene with unexpected genomic regions, highlighting the potential for CRISPR to induce complex structural variations with potentially oncogenic consequences [7].

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Detection

RNA-sequencing with De Novo Transcript Assembly

Protocol Summary: This method enables comprehensive detection of transcript-level unintended effects without prior knowledge of potential outcomes [7].

- RNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality total RNA from CRISPR-edited cells and appropriate controls using column-based purification methods.

- Library Preparation: Prepare stranded RNA-seq libraries with ribosomal RNA depletion to ensure comprehensive transcriptome coverage.

- Sequencing: Perform paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp) on Illumina platforms to a minimum depth of 30-50 million reads per sample.

- Data Analysis:

- Perform quality control using FastQC and trim adapters with Trimmomatic.

- Conduct de novo transcript assembly using Trinity with default parameters.

- Align assembled transcripts to the reference genome using Minimap2.

- Identify aberrant transcripts, including exon skipping, novel exons, and fusion events through comparative analysis with control samples.

- Validate findings through PCR and Sanger sequencing of candidate aberrant transcripts.

Key Advantage: This approach identified an inter-chromosomal fusion event in the NF1 knockout experiment that was completely undetectable by DNA-focused methods [7].

CRAFTseq: Multi-omic Single-Cell Analysis

Protocol Summary: CRAFTseq (CRISPR by ADT, flow cytometry and transcriptome sequencing) enables simultaneous detection of editing outcomes and functional effects in single cells [12].

- Cell Preparation: Edit primary cells or cell lines using CRISPR RNPs or base editors via electroporation.

- Cell Hashing: Label different conditions with unique barcoded antibodies for multiplexing.

- Single-Cell Sorting: Sort single cells into 384-well plates containing lysis buffer.

- Library Construction:

- Perform nested PCR to amplify targeted genomic regions from single-cell lysates.

- Conduct full-length RNA-seq using a modified FLASH-seq protocol.

- Include antibody-derived tags (ADTs) for surface protein quantification.

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on Illumina platforms with appropriate index reads.

- Data Integration:

- Call genotypes from targeted DNA amplicons with high confidence using specialized pipelines.

- Cluster cells based on transcriptome and protein expression.

- Correlate specific editing outcomes with transcriptional and proteomic changes.

Key Advantage: CRAFTseq achieves approximately 58% alignment of RNA reads to the transcriptome and recovers a mean of 5,089 genes and 57,540 UMIs per cell, enabling high-resolution correlation of genotypes with molecular phenotypes [12].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) for Copy Number Validation

Protocol Summary: ddPCR provides absolute quantification of copy number variations resulting from large deletions [7] [13].

- Assay Design: Design TaqMan probes targeting the region of interest and a reference gene.

- Partitioning: Partition each sample into approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized droplets.

- PCR Amplification: Perform endpoint PCR on the droplet emulsion.

- Quantification: Count positive and negative droplets for target and reference assays.

- Copy Number Calculation: Calculate absolute copy number using Poisson statistics.

Application Example: In rice genome editing experiments, ddPCR successfully validated Cas3 nuclease-mediated reduction in OsMTD1 gene copy number, providing precise quantification of CNV modifications [13].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Detecting CRISPR Unintended Effects

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for CRISPR Validation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Trinity | De novo transcriptome assembly | Identified fusion transcripts and exon skipping in NF1 KO [7] |

| Droplet Digital PCR | Absolute nucleic acid quantification | Verified copy number variations in SRGAP2 and rice CNV studies [7] [13] |

| FLASH-seq Reagents | Single-cell full-length RNA-seq | Enabled CRAFTseq transcriptome analysis with 5,089 genes/cell [12] |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Multiplexed single-cell experiments | Allowed pooling of multiple conditions in CRAFTseq [12] |

| Long-Range PCR Kits | Amplification of large genomic regions | Detection of large deletions spanning multiple exons |

| Barcoded Oligo-dT Primers | Single-cell RNA-seq | Captured transcriptomes in CRAFTseq platform [12] |

| Cas3 Nuclease | Large-scale deletion generation | Created CNV variants in rice OsMTD1 gene [13] |

| PROTAC BRD4 Degrader-17 | PROTAC BRD4 Degrader-17, MF:C49H47N7O9, MW:877.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Chisocheton compound F | 20,21,22,23-Tetrahydro-23-oxoazadirone | Research-grade 20,21,22,23-Tetrahydro-23-oxoazadirone, a limonoid from Meliaceae. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The evidence from multiple CRISPR editing experiments demonstrates that conventional DNA-centric validation approaches are insufficient for capturing the full spectrum of unintended on-target effects. Based on comparative analysis of detection methods:

RNA-sequencing with de novo assembly should be implemented as a standard validation step, as it uniquely identifies fusion transcripts and exon skipping events that escape DNA-based detection [7].

Multi-omic single-cell approaches like CRAFTseq provide the highest resolution view of editing outcomes, enabling direct correlation of specific genotypes with transcriptomic and proteomic consequences [12].

Absolute quantification methods including ddPCR offer crucial validation for structural variants identified through sequencing, providing orthogonal confirmation of findings [7] [13].

As CRISPR technologies advance toward clinical applications, comprehensive characterization of unintended effects becomes increasingly critical for ensuring both experimental validity and therapeutic safety. The methods and data presented here provide researchers with a framework for moving beyond simple indel analysis to fully characterize the structural consequences of genome editing.

The revolutionary power of CRISPR genome editing is undeniable, but its true value in research and therapy is wholly dependent on the rigorous validation of editing outcomes. A comprehensive validation pipeline is crucial to confirm intended on-target modifications, detect unwanted off-target effects, and ultimately, define the success of an experiment. While numerous detection methods exist, their performance varies significantly in accuracy, sensitivity, and cost. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of CRISPR analysis techniques, framing them within a strategic validation pipeline to help researchers select the optimal methods for their specific applications.

Chapter 1: The Critical Need for Validation in CRISPR Experimentation

CRISPR-Cas9 functions by creating double-strand breaks in DNA, which are subsequently repaired by the cell's innate repair mechanisms. The primary pathway, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), is error-prone and often results in insertions or deletions (indels). However, the editing outcomes are not always predictable or clean. Beyond intended indels, CRISPR can introduce complex outcomes like large deletions, chromosomal rearrangements, and structural variations [14].

Furthermore, a significant safety concern in therapeutic applications is off-target activity, where the nuclease cuts at unintended sites in the genome, potentially leading to adverse effects, including oncogenic mutations [14]. Traditional validation methods that focus solely on DNA sequence at the target site can miss these critical events. RNA-sequencing has revealed unanticipated transcriptional changes post-editing, such as exon skipping, inter-chromosomal fusion events, and the unintentional modification of neighboring genes [7]. Relying on a single, limited method can thus provide a false sense of security, underscoring the need for a multi-faceted validation pipeline that interrogates the genome, transcriptome, and phenome.

Chapter 2: A Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Detection Methods

Numerous molecular techniques have been adapted to detect and quantify CRISPR edits. The choice of method depends on the required resolution, throughput, and available resources. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the most common approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Methods for Detecting CRISPR-Cas9 Edits

| Method | Detection Principle | Key Metric | Throughput | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) / SURVEYOR [15] [16] | Enzymatic cleavage of mismatched heteroduplex DNA | Indirect quantification of indel frequency via gel electrophoresis | Medium | Low cost; simple workflow; quick results [17] | Low accuracy and sensitivity; under-represents efficiency; no sequence information [15] [17] [16] |

| Sanger Sequencing + Deconvolution Software (ICE, TIDE) [15] [17] | Capillary electrophoresis of PCR amplicons deconvoluted via algorithms | Indel frequency and sequence context | Low to Medium | Cost-effective; provides sequence data; user-friendly software (e.g., ICE) [17] | Lower sensitivity for low-frequency edits (<5-10%); limited to small indels; results depend on base-calling software [15] |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) [18] | Amplification of target DNA sequence using specific primers | Cycle threshold (Ct) value indicating relative abundance | High | High throughput; low cost per sample | Fundamentally mismatched for KO validation; detects mRNA, not genomic DNA; poor detection of small indels [18] |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) [15] | Partitioned PCR enabling absolute quantification of target sequences | Copies per microliter | High | High sensitivity and accuracy; absolute quantification without standards [15] | Requires specific probe/assay design; limited information on edit identity |

| Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (AmpSeq) [15] [16] | Next-generation sequencing of PCR-amplicons covering the target site | Indel frequency and precise sequence of each read | Medium to High | Gold standard for sensitivity and accuracy; provides complete mutational spectrum [15] | Higher cost and longer turnaround time than other methods [15] |

| Single-Cell DNA Sequencing (scDNA-seq) [19] [14] | Targeted DNA sequencing of thousands of individual cells | Editing co-occurrence, zygosity, and clonality at single-cell resolution | Medium | Reveals unique editing patterns in every cell; measures zygosity and complex heterogeneity [14] | Specialized equipment and expertise required; higher cost than bulk methods |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

A 2025 systematic benchmarking study directly compared the accuracy of several quantification methods against targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) as the gold standard. The results provide critical insights for method selection.

Table 2: Benchmarking Accuracy of CRISPR Quantification Methods vs. AmpSeq [15]

| Method | Performance Characteristics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| PCR-Capillary Electrophoresis (PCR-CE/IDAA) | High Accuracy | Quantified edit frequencies showed strong correlation with AmpSeq data. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | High Accuracy | Demonstrated high sensitivity and accurate quantification compared to AmpSeq. |

| Sanger Sequencing (Deconvolution Tools) | Variable Accuracy | Accuracy was highly dependent on the base-calling algorithm and software used. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) | Low Accuracy | Consistently under-represented the true editing efficiency in a non-linear fashion. |

This data strongly suggests that for applications requiring precise quantification, PCR-CE/IDAA and ddPCR are reliable alternatives to AmpSeq, whereas T7E1 assays are not recommended for quantitative conclusions [15] [17].

Chapter 3: Building Your Validation Pipeline: A Strategic Workflow

A robust validation pipeline is multi-stage, employing different techniques at each step to balance rigor with practicality. The following workflow diagram and subsequent explanation outline a comprehensive strategy.

Stages of the Validation Pipeline:

Initial Rapid Triage: Immediately after generating a pool of edited cells, use a fast and cost-effective method like Sanger sequencing with ICE analysis or a T7E1 assay to confirm that editing has occurred [17]. This step is critical for deciding whether to proceed to single-cell cloning or re-optimize the transfection.

Comprehensive Bulk Characterization: For a detailed view of the editing landscape, use targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq). This provides the precise spectrum of indels at the target site and can be adapted to screen nominated off-target sites [15] [16]. This is the recommended method for thorough, publication-quality validation.

Advanced Single-Cell Resolution: For therapeutic development or when assessing complex, heterogeneous populations, single-cell DNA sequencing (e.g., Tapestri) is invaluable. It can determine the co-occurrence of edits, their zygosity (homozygous/heterozygous), and clonality, revealing heterogeneity that bulk methods miss [14].

Functional Quality Control: DNA editing does not guarantee functional knockout. Validation should include:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Validation

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| rhAmpSeq CRISPR Analysis System [16] | Targeted amplicon sequencing system for highly accurate, multiplexed on- and off-target quantification. | Includes optimized PCR technology and a cloud-based analysis pipeline. |

| Tapestri Platform [14] | Single-cell DNA sequencing platform for resolving co-editing, zygosity, and clonality. | Custom amplicon panels can be designed for on- and off-target sites. |

| Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) [17] | Software for deconvoluting Sanger sequencing traces to determine indel frequency. | Free, web-based tool; good balance of cost and accuracy for knockout validation. |

| Alt-R Genome Editing Detection Kit [16] | Kit for performing the T7E1 mismatch cleavage assay. | Provides a simple, gel-based method for quick confirmation of edits. |

| Validated sgRNA Libraries [20] | Pre-designed libraries of sgRNAs with high on-target efficiency, minimizing screening burden. | Libraries like "Vienna" (based on VBC scores) show superior performance in loss-of-function screens. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) Systems [15] | Platform for absolute quantification of editing efficiency with high sensitivity. | Accurate alternative to AmpSeq for quantifying specific edits. |

Establishing a rigorous validation pipeline is non-negotiable for credible CRISPR research. The data clearly shows that while simple methods like T7E1 have a role in initial triage, they lack the accuracy required for definitive conclusions. For most applications, Sanger sequencing with deconvolution software like ICE provides a strong balance of cost and information for routine knockouts, while targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) remains the gold standard for comprehensive, sensitive characterization of editing outcomes. As the field advances toward clinical applications, single-cell DNA sequencing is emerging as a powerful technology to ensure the highest safety standards by revealing the complex heterogeneity within edited cell populations. By strategically layering these methods, researchers can build a validation pipeline that truly defines—and ensures—the success of their CRISPR experiments.

A Practical Guide to Sequencing Validation Methods: From T7E1 to NGS

In the field of CRISPR-based genome editing, accurately measuring on-target editing efficiency is a critical step for both fundamental research and clinical application development [21]. Enzymatic mismatch detection assays provide a rapid and accessible method for initial screening of editing success. Among these, the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay has been a long-standing standard, while newer reagents like Authenticase have emerged with claims of enhanced performance [22]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two enzymatic methods, detailing their protocols, performance characteristics, and appropriate applications within a comprehensive CRISPR validation workflow.

Mechanism of Action and Detection Capabilities

Both T7 Endonuclease I and Authenticase function by recognizing and cleaving mismatched regions in double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), which arise when edited and wildtype DNA strands hybridize after PCR amplification.

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1)

T7E1 recognizes and cleaves at distorted DNA structures, including mismatches and small insertions or deletions (indels) [23]. It cleaves upstream of the mismatch site, generating discrete DNA fragments that can be visualized via gel electrophoresis [23]. A key limitation is that it may overlook single-nucleotide changes and its sensitivity is highly dependent on reaction conditions [16] [23].

Authenticase

Authenticase is described as a proprietary mixture of structure-specific nucleases that cleaves outside the mismatch and indel regions on dsDNA [24] [25]. It is reported to recognize a broader spectrum of mismatches, including single base mismatches (e.g., C/C, T/C, A/C, T/G, G/G, T/T, A/A) and indels ranging from 1 to 10 base pairs [24]. The formulation is also noted for having limited non-specific activity on perfectly matched homoduplex DNA [24].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of each assay based on available product information and comparative studies.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of T7 Endonuclease I and Authenticase Assays

| Feature | T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) | Authenticase |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Composition | Single enzyme [23] | Proprietary mixture of nucleases [24] |

| Recognition Site | Cleaves upstream of the mismatch [23] | Cleaves outside the mismatch/indel region [24] |

| Detection Range | Small indels; less sensitive to single nucleotides [16] [23] | Indels (1-10 bp) and specific single-base mismatches [24] |

| Primary Applications | Mismatch detection for genome editing validation [23] | Error-correction in gene synthesis; mismatch detection assay [24] |

| Advantages | Simple, inexpensive, and provides rapid results [23] | Broader mismatch recognition; reduced non-specific cleavage [24] |

| Limitations | Semi-quantitative; requires optimization; may miss single-nucleotide edits [21] [23] | Research use only; not for human or animal diagnostics [24] |

A recent comparative analysis of methods for assessing on-target gene editing noted that while the T7E1 digestion is quick, it is only semi-quantitative, "even when using densitometric analysis of DNA band intensities" [21]. The study highlighted that T7E1 assays lack the sensitivity of more advanced quantitative techniques like sequencing-based methods [21]. In its product documentation, New England Biolabs states that Authenticase "can replace T7 Endonuclease I in the mismatch detection assay" and that it "outperforms T7 Endo I in detecting CRISPR-induced on-target mutations across a broad range of mutations/wild-types" [24] [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay Protocol

The T7E1 assay is a well-established method for detecting CRISPR-induced indels. The following protocol is synthesized from published methodologies [23] [26].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target genomic region from both edited and control (wildtype) samples using a high-fidelity PCR master mix. The amplicon should be 400-800 base pairs in length, with the target site located such that the smallest expected cleavage product is >100 bp [23].

- Heteroduplex Formation: Purify the PCR products. To form heteroduplexes, mix the PCR products from edited and control samples, denature at 95°C for 5 minutes, and then reanneal by ramping down the temperature to 25°C at a rate of 0.1°C per second [26].

- T7E1 Digestion:

- Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis:

- Resolve the digestion products on a 1% to 1.5% agarose gel containing a DNA stain [21] [26].

- Visualize the gel and quantify the band intensities. The editing efficiency (indel frequency) can be estimated using the formula:

- Indel Frequency (%) = [1 - (1 / (a + b))] × 100

- Where

aandbare the integrated intensities of the cleavage bands, andcis the intensity of the undigested, parent band [23].

Authenticase Assay Protocol

The protocol for Authenticase shares a similar workflow with T7E1 but uses different reaction conditions optimized for the enzyme mixture [24].

- PCR Amplification and Heteroduplex Formation: This initial step is identical to the T7E1 protocol: amplify the target region and form heteroduplexes by denaturing and reannealing the PCR products.

- Authenticase Digestion:

- Set up the digestion reaction using the purified, reannealed PCR product.

- Use the supplied 1X Authenticase Reaction Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 100 µg/ml Recombinant Albumin, pH 8.0 @ 25°C) [24].

- Incubate the reaction at 42°C for the recommended time (refer to the product manual for specific duration) [24].

- Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze the cleavage products via agarose gel electrophoresis, similar to the T7E1 assay. Quantify band intensities to estimate editing efficiency.

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the shared workflow for both enzymatic mismatch detection assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of these assays requires a set of key reagents. The following table lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Enzymatic Mismatch Assays

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Product & Source |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Amplifies the target genomic region with low error rates to prevent false positives. | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (NEB M0494) [21] |

| Mismatch-Specific Endonuclease | Cleaves heteroduplex DNA at mismatch sites to reveal editing events. | T7 Endonuclease I (NEB M0302) [21] or Authenticase (NEB M0689) [24] |

| Specialized Detection Kit | Provides optimized, complete reagent sets for streamlined workflow. | Alt-R Genome Editing Detection Kit (IDT) [16] or EnGen Mutation Detection Kit (NEB E3321) [22] |

| Gel Visualization Stain | Stains DNA for visualization and quantification after electrophoresis. | Ethidium Bromide or GelRed [21] |

| DNA Clean-Up Kit | Purifies PCR products prior to heteroduplex formation and digestion. | Gel and PCR Clean-Up Kit [21] |

| [3,5 Diiodo-Tyr7] Peptide T | [3,5 Diiodo-Tyr7] Peptide T, MF:C35H53I2N9O16, MW:1109.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antitubercular agent-12 | Antitubercular agent-12, MF:C13H7BrN4O5, MW:379.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion: Position in CRISPR Validation Workflow

While enzymatic assays like T7E1 and Authenticase are valuable for initial, rapid screening due to their low cost and speed, their role in a comprehensive validation strategy must be considered alongside their limitations [21] [23].

The most significant limitation of both methods is that they are inference-based; they indicate that a sequence change has occurred but do not reveal the exact nucleotide composition of the edit [16]. They are semi-quantitative and may not detect all types of edits with equal sensitivity. Therefore, they are ideally used as a primary screening tool to identify candidate gRNAs or editing conditions with high activity.

For a complete understanding of editing outcomes, including precise sequence changes and off-target effects, these enzymatic methods should be followed by Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [16]. NGS provides the high resolution necessary to definitively characterize the spectrum of indels and base substitutions, making it the gold standard for confirmatory analysis [22] [16]. As one source concludes, "NGS is the recommended method for full investigation of CRISPR edits" [16].

Both T7 Endonuclease I and Authenticase offer efficient pathways for the initial detection of CRISPR-induced mutations. The classic T7E1 assay remains a widely used, cost-effective option. In contrast, Authenticase presents a potentially enhanced alternative with a broader recognition profile for mismatches and indels. The choice between them depends on the required sensitivity, the specific types of edits being screened for, and available resources. Crucially, neither method replaces the need for sequencing-based validation to obtain a complete and quantitative picture of genome editing outcomes, underscoring the importance of a multi-tiered analytical approach in rigorous scientific research.

Validating CRISPR edits is a critical step in genome engineering workflows, and the choice of analysis method directly impacts the accuracy and reliability of research outcomes. While next-generation sequencing (NGS) offers comprehensive detail, its cost and complexity often render it impractical for routine validation. This has established Sanger sequencing coupled with sophisticated analysis tools as a fundamental approach for indel characterization. Among available computational tools, the Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) method has emerged as a particularly robust solution, offering NGS-comparable quality with the accessibility and low cost of Sanger sequencing [27] [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of leading Sanger-based analysis methods, detailing their performance, experimental protocols, and appropriate applications to inform researchers in selecting the optimal strategy for their CRISPR validation needs.

Methodological Comparison: ICE, TIDE, and T7E1

Various methods have been developed to assess CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of three common techniques.

Table 1: Key Features of Common CRISPR Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Quantitative Output | Indel Sequence Data | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) | Computational decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces [27] | Yes (Indel %, KO Score, R²) [27] | Yes, including complex edits [27] | NGS-level analysis from Sanger data; user-friendly [9] | Accuracy may vary with highly complex indel mixtures [4] |

| TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) | Computational decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces [28] | Yes (Indel frequency, R²) [9] | Limited, best for simple indels [4] [9] | Established, widely-used method | Struggles with complex edits and large insertions [4] [9] |

| T7E1 Assay | Enzyme-based cleavage of heteroduplex DNA [28] [29] | Semi-quantitative [28] | No [9] | Fast, low-cost, and simple [9] | Lacks sequence-level detail; can underestimate efficiency [4] |

Performance and Experimental Data

A systematic 2024 comparison of computational tools using artificial sequencing templates with predetermined indels revealed important performance nuances [4]. While all tools estimated indel frequency with reasonable accuracy for simple indels, the estimated values became more variable among tools with more complex indels. DECODR provided the most accurate estimations for most samples, though TIDE-based TIDER was superior for analyzing knock-in efficiency of short epitope tags [4].

Independent research confirms that ICE analysis results are highly comparable to NGS, with a reported correlation of R² = 0.96 [9]. ICE also demonstrates capability to analyze edits from multiple gRNAs and non-SpCas9 nucleases like Cas12a and MAD7, a limitation of many traditional tools [27] [30].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of ICE and TIDE from Experimental Data

| Parameter | ICE | TIDE | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation with NGS (R²) | 0.96 [9] | Not specified | Demonstrates ICE's high accuracy |

| Analysis of Complex Edits | Supported [27] | Limited [4] | Complex edits include those from multiple gRNAs |

| Knock-in Analysis | Supported (Knock-in Score) [27] [30] | Limited, requires TIDER extension [4] | ICE provides a dedicated Knock-in Score metric |

| Typical Output Metrics | Indel %, KO Score, KI Score, R² [27] | Indel frequency, R² [9] | KO Score estimates functional knockout likelihood |

Experimental Protocol for Sanger Sequencing and ICE Analysis

Proper experimental execution from sample preparation to sequencing is fundamental for obtaining reliable ICE results. The following protocol outlines the critical steps.

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Genomic DNA Extraction: After CRISPR editing, harvest cells and extract genomic DNA. Use appropriate methods (e.g., phenol-chloroform for tissues, column-based kits for cells) to obtain high-purity DNA with OD260/OD280 ratios of 1.8-2.0 [31].

- PCR Amplification: Design primers flanking the target site to generate amplicons of optimal length (typically 300-500 bp). Use high-fidelity DNA polymerase to minimize PCR errors. Purify PCR products to remove primers and enzymes, ensuring a clean template for sequencing [31].

Sanger Sequencing

- Primer Design: Design a sequencing primer that anneals 50-150 bp upstream of the CRISPR cut site. Follow standard principles: 18-25 bases length, avoidance of secondary structures, and Tm ~50-60°C [31].

- Sequencing Reaction: Submit purified PCR products and the sequencing primer to a sequencing facility. Ensure adequate template concentration (10-50 ng/μL for PCR products) [31].

- Quality Control: Upon receipt, inspect sequencing chromatograms (.ab1 files) for quality. High-quality traces have low background noise, even peak spacing, and no signal degradation after the cut site [32].

ICE Analysis Workflow

- Data Upload: Access the ICE web tool (provided by Synthego or EditCo) [27] [30]. Upload the control (un-edited) and edited sample .ab1 files.

- Parameter Input: Enter the gRNA target sequence (excluding the PAM sequence) and select the nuclease used (e.g., SpCas9, Cas12a) from the dropdown menu [27].

- Analysis Execution: Initiate the analysis. For knock-in experiments, also provide the donor template sequence (up to 300 bp) [27] [30].

- Result Interpretation: Review the output dashboard:

- Indel Percentage: The overall editing efficiency [27] [30].

- Knockout Score: The proportion of edits likely to cause a functional gene knockout (frameshift or large ≥21 bp indel) [27] [30].

- R² Value: The goodness-of-fit; values >0.9 indicate high-confidence decomposition [27] [30].

- Indel Spectrum: Detailed breakdown of specific insertion and deletion sequences and their relative abundances [27].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process from sample preparation to final analysis:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful indel characterization depends on specific, high-quality reagents. The table below lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Sanger Sequencing and ICE Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies the target genomic region for sequencing | Reduces PCR errors that can be misinterpreted as indels [31] |

| PCR Purification Kit | Removes primers, dNTPs, and enzymes post-amplification | Ensures clean template for sequencing reactions [31] |

| Sanger Sequencing Service | Generates sequencing chromatograms (.ab1 files) | Provider should return high-quality, low-noise traces [31] |

| ICE Software Tool | Computational analysis of Sanger data for indel characterization | Web-based platform; requires gRNA sequence and nuclease type [27] |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Targets the Cas nuclease to the genomic locus | Sequence is critical input for ICE analysis [27] |

Sanger sequencing remains an indispensable tool for validating CRISPR edits, particularly when paired with advanced analysis tools like ICE. While TIDE offers a valid approach for basic editing assessments and T7E1 provides a rapid, low-cost alternative, ICE delivers superior detail, accuracy, and versatility for characterizing complex indel profiles. Its performance, which closely mirrors NGS at a fraction of the cost, establishes the Sanger-ICE pipeline as a powerful and efficient gold standard for most indel characterization workflows. Researchers should select their method based on the required level of detail, experimental complexity, and available resources, but can rely on the robust, data-rich outputs of ICE for the majority of their CRISPR validation needs.

The advent of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling precise modifications in genomic DNA across diverse organisms. However, verifying the accuracy and specificity of these edits remains a critical challenge. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides an powerful suite of tools for this validation, with amplicon sequencing and whole-transcriptome sequencing representing two complementary approaches. Amplicon sequencing focuses on deep sequencing of specific target regions to quantify editing efficiency and detect off-target effects at predicted sites, while whole-transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) captures the broader transcriptional consequences of genetic modifications, including unexpected perturbations in gene expression and splicing alterations. This guide objectively compares these methodologies, providing experimental data and protocols to inform researchers' validation strategies.

The critical importance of rigorous CRISPR validation stems from the potential for unintended effects. Off-target mutations with frequencies below 0.5% often remain undetected by conventional methods but can be identified with advanced NGS techniques [33]. Furthermore, CRISPR can cause unanticipated transcriptional changes—including inter-chromosomal fusion events, exon skipping, chromosomal truncation, and unintended modification of neighboring genes—that are not detectable by DNA-focused analysis alone [8] [7]. As CRISPR-based therapies advance toward clinical applications, comprehensive validation using these NGS methods becomes increasingly essential for ensuring efficacy and safety.

Technical Comparison of Amplicon and Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing

Amplicon sequencing (targeted amplicon sequencing) employs PCR to amplify specific genomic regions of interest, including CRISPR target sites and predicted off-target locations, followed by high-coverage sequencing [34]. This targeted approach enables ultra-deep sequencing—reaching coverage depths of thousands to millions of reads—allowing for the detection of very low-frequency mutations. In contrast, whole-transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) provides a global view of the transcriptome by sequencing all expressed genes, typically with lower per-transcript coverage but much broader scope [35]. While amplicon sequencing directly assesses DNA-level modifications, RNA-seq reveals the functional consequences of these edits at the transcriptional level, including changes in gene expression, alternative splicing, and the emergence of novel fusion transcripts.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each method:

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Amplicon and Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing

| Feature | Amplicon Sequencing | Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | Specific genomic loci (DNA) | Entire transcriptome (RNA) |

| Primary Application in CRISPR Validation | On-target efficiency, indel quantification, off-target validation | Transcriptional profiling, aberrant splicing, fusion transcripts, unexpected expression changes |

| Key Strength | High sensitivity for low-frequency mutations (<0.1%-0.00001%) [33] [36] | Hypothesis-free, genome-wide detection of functional impacts |

| Key Limitation | Limited to pre-determined targets; misses novel off-target sites | Does not directly detect DNA mutations; higher RNA input requirement |

| Typical Read Depth | Very high (>10,000x) | Moderate (20-50 million reads/sample) |

| Best Suited For | Validating predicted edits, quantifying editing efficiency, sensitive off-target screening | Comprehensive safety assessment, functional annotation of edits, discovery of unexpected effects |

Performance Data and Experimental Evidence

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Sensitivity is a critical parameter for CRISPR validation, particularly for detecting rare off-target events. Amplicon sequencing, especially when coupled with specialized enrichment techniques, demonstrates exceptional sensitivity. One study described a CRISPR amplification method that enriched mutant DNA over wild-type DNA, enabling the detection of indel mutations with a frequency as low as 0.00001%—significantly below the detection limit of conventional targeted amplicon sequencing [33]. This method detected off-target mutations at a 1.6 to 984-fold higher rate than standard methods. For standard targeted amplicon sequencing, the typical lower limit of detection is approximately 0.1% of alleles in a cell population [36]. Single-cell DNA sequencing approaches targeting predetermined loci can achieve a similar sensitivity of around 0.1%, with the potential for further improvement by increasing the number of cells analyzed [36].

Whole-transcriptome sequencing also offers advantages in detecting minority transcripts and quantitative expression changes. While typically not used for detecting very low-frequency DNA mutations, its ability to identify chimeric transcripts and allele-specific expression provides a different dimension of sensitivity to functional consequences that may affect only a subset of cells [7].

Comprehensiveness and Unbiased Discovery

While amplicon sequencing excels at targeted sensitivity, whole-transcriptome sequencing provides a comprehensive, unbiased view of CRISPR effects. A key advantage of RNA-seq is its ability to identify unexpected transcriptional changes that DNA-based methods miss entirely. Researchers analyzing RNA-seq data from four CRISPR knockout experiments identified numerous unanticipated events, including an inter-chromosomal fusion, exon skipping, chromosomal truncation, and the unintentional transcriptional modification and amplification of a neighboring gene [7]. These findings highlight that DNA confirmation alone is insufficient for a complete understanding of CRISPR outcomes.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) represents the most comprehensive DNA-based approach for unbiased validation. In one study, WGS of CRISPR/Cas9-engineered NF-κB reporter mice successfully validated the intended genetic modifications while also characterizing off-target effects across the entire genome [37]. This approach detected all CRISPR-induced variants without prior assumptions about their locations, though it comes with higher costs and computational demands than targeted approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Mutation Types Detected by Different Validation Methods

| Mutation Type | Amplicon Sequencing | Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing | Whole-Genome Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small indels (on-target) | Yes | Indirectly via transcript analysis | Yes |

| Small indels (off-target) | Only at predicted sites | No | Yes |

| Large structural variations | No | Yes (via aberrant transcripts) | Yes |

| Chromosomal translocations | No | Yes (via fusion transcripts) | Yes |

| Exon skipping/alternative splicing | No | Yes | No |

| Gene expression changes | No | Yes | No |

| Unexpected integration events | Limited | Yes | Yes |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Targeted Amplicon Sequencing for CRISPR Validation

The following workflow outlines a robust protocol for targeted amplicon sequencing to validate CRISPR edits, based on established methods [33] [34]:

Amplicon Sequencing Workflow for CRISPR Validation

Step 1: DNA Extraction and Amplification Extract high-quality genomic DNA from CRISPR-edited cells. Design primers to flank the CRISPR target site(s) and all in silico predicted off-target sites. Include partial Illumina sequencing adapters in these primers. Amplify target regions using a high-fidelity PCR polymerase [34].

Step 2: Optional CRISPR Enrichment For enhanced sensitivity to rare mutations, implement a CRISPR-based enrichment step. Incubate the initial PCR amplicons with the same CRISPR effector (Cas9 or Cas12a) and guide RNA used in the original editing experiment. The CRISPR complex will cleave wild-type sequences, thereby enriching for mutant alleles that resist cleavage. Perform additional PCR amplification after cleavage [33].

Step 3: Library Preparation and Sequencing In a second PCR reaction, add full Illumina sequencing adapters and unique dual indices to enable sample multiplexing. Quantify the final libraries using fluorometry, pool equimolar amounts, and sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., MiSeq) with sufficient read depth to achieve the desired sensitivity [34].

Step 4: Data Analysis Process raw sequencing data through a standardized bioinformatics pipeline: (1) Demultiplex reads by sample-specific barcodes; (2) Trim adapter sequences; (3) Align reads to the reference genome; (4) Use specialized tools like CRISPResso2 [38] to quantify indel frequencies, characterize mutation spectra, and determine frameshift proportions.

Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing for Functional Assessment

The protocol below details whole-transcriptome sequencing to evaluate transcriptional consequences of CRISPR editing:

RNA Sequencing Workflow for CRISPR Functional Assessment

Step 1: RNA Extraction and Quality Control Extract total RNA from CRISPR-edited cells and appropriate control cells using a method that preserves RNA integrity. Assess RNA quality using an instrument such as an Agilent Bioanalyzer; an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) greater than 8.0 is generally recommended for reliable sequencing results [7] [35].

Step 2: Library Preparation For standard RNA-seq: Deplete ribosomal RNA or select polyadenylated RNA to enrich for mRNA. Fragment the RNA or resulting cDNA, then add sequencing adapters. For targeted transcriptome approaches like AmpliSeq: Convert RNA to cDNA, then amplify targeted genes using a multiplexed primer pool [35].

Step 3: Sequencing Sequence libraries on an appropriate NGS platform. Illumina HiSeq or NovaSeq systems are commonly used for standard RNA-seq, while Ion Torrent Proton is compatible with targeted approaches like AmpliSeq. Aim for 20-50 million reads per sample for standard differential expression analysis, though deeper sequencing may be required for detecting rare transcripts or complex splicing events [35].

Step 4: Bioinformatics Analysis A comprehensive RNA-seq analysis pipeline should include: (1) Read alignment to the reference genome using splice-aware aligners like STAR; (2) Differential expression analysis with tools such as DESeq2; (3) Alternative splicing analysis using tools like rMATS; (4) Fusion transcript detection with tools like FusionCatcher; (5) de novo transcript assembly using platforms like Trinity to identify novel transcripts that may result from CRISPR editing [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of NGS-based CRISPR validation requires specific reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential components for establishing these workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for NGS-based CRISPR Validation

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | High-fidelity DNA polymerase | Amplification of target loci with minimal errors | GoTaq Flexi DNA Polymerase [39] |

| RNA extraction kit with DNase treatment | Isolation of high-quality, DNA-free RNA | High Pure RNA Isolation Kit [7] | |

| Reverse transcriptase kit | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit [35] | |

| Library Construction | Targeted amplicon panel | Multiplexed amplification of specific gene targets | Ion AmpliSeq Transcriptome Human Gene Expression Kit [35] |

| Sequencing adapters and barcodes | Sample multiplexing and platform compatibility | Illumina sequencing adapters, Native Barcoding Kit [34] [38] | |

| Sequencing & Analysis | NGS sequencing platform | High-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing | Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq, Ion Torrent Proton [34] [35] |

| CRISPR analysis software | Quantification of editing efficiency and indel characterization | CRISPResso2, nCRISPResso2 (nanopore-compatible) [38] | |

| Transcriptome analysis suite | Differential expression, splicing, and fusion detection | Trinity for de novo assembly [7] | |

| Validation & QC | Bioanalyzer system | Quality control of nucleic acids and libraries | Agilent Bioanalyzer for RNA IQC [35] |

| 1-Bromo-3-ethylbenzene-d5 | 1-Bromo-3-ethylbenzene-d5, MF:C8H9Br, MW:190.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 1-Bromo-4-chlorobutane-d8 | 1-Bromo-4-chlorobutane-d8, MF:C4H8BrCl, MW:179.51 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Amplicon sequencing and whole-transcriptome sequencing offer complementary strengths for CRISPR validation. Amplicon sequencing provides exceptional sensitivity for quantifying on-target efficiency and validating predicted off-target sites, with detection limits reaching 0.00001% using advanced enrichment methods [33]. Whole-transcriptome sequencing delivers comprehensive functional assessment, detecting unexpected transcriptional consequences that DNA-based methods miss, including fusion transcripts, aberrant splicing, and unintended effects on neighboring genes [7].

For researchers designing CRISPR validation strategies, the following evidence-based approach is recommended:

- For routine validation of editing efficiency: Implement targeted amplicon sequencing with tools like CRISPResso2 for cost-effective, high-sensitivity quantification of indels at specified loci.

- For comprehensive safety profiling: Combine amplicon sequencing with whole-transcriptome sequencing to assess both specific mutations and genome-wide functional impacts.

- When working with novel cell lines or therapeutic applications: Include whole-transcriptome analysis to identify cell-type-specific effects and unexpected transcriptional changes that could impact experimental results or clinical safety.

- For the most thorough unbiased assessment: Consider whole-genome sequencing when resources allow, as it provides the most complete picture of on-target and off-target modifications throughout the genome [37].

The integration of these NGS methodologies provides a robust framework for validating CRISPR edits, each contributing unique and essential information to fully characterize genetic modifications and their functional consequences.

The advent of CRISPR genome editing has revolutionized functional genomics, enabling precise manipulation of genes to study their function in disease development [40]. However, CRISPR interventions can cause many unanticipated transcriptional changes that are not detectable through DNA sequencing alone [8]. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides a powerful approach to fully characterize these transcriptional consequences, particularly when studying non-model organisms or systems where a reference genome is unavailable. In these contexts, de novo transcriptome assembly using tools like Trinity enables comprehensive transcript characterization without requiring a reference genome, making it an essential methodology for validating the full impact of CRISPR experiments [41] [42].

Trinity De Novo Assembly: Core Methodology and Workflow

Trinity is a novel method for efficient de novo reconstruction of transcriptomes from RNA-Seq data, combining three independent software modules that process large volumes of RNA-seq reads sequentially [42] [43]. Unlike genome-guided approaches that depend on reference genomes, Trinity's de novo assembly capability makes it particularly valuable for studying non-model organisms, cancer samples with altered genomes, or any system where a high-quality reference genome is unavailable [41].

The Trinity platform operates through three consecutive stages, each with distinct functions in the transcript reconstruction process [41] [42]:

Stage 1: Inchworm