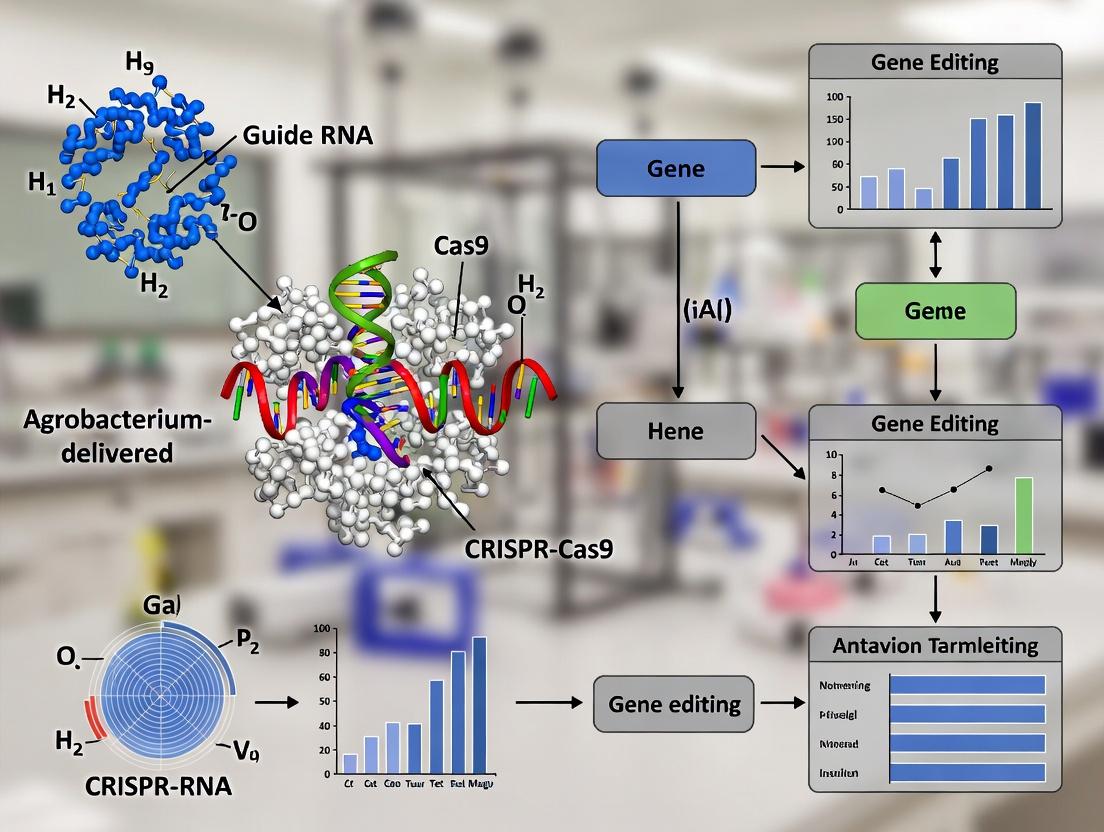

Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery: A Comprehensive Guide for Genome Editing in Plants and Beyond

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and biotechnologists on utilizing Agrobacterium tumefaciens as a vector for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing.

Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery: A Comprehensive Guide for Genome Editing in Plants and Beyond

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and biotechnologists on utilizing Agrobacterium tumefaciens as a vector for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. It explores the foundational biology of Agrobacterium's natural gene transfer mechanism, details step-by-step protocols for vector design and plant transformation, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and compares this method to alternative delivery systems. The focus is on practical application and achieving high-efficiency, heritable edits in plants, with implications for crop improvement and foundational research.

Agrobacterium and CRISPR-Cas9: Understanding the Synergy for Plant Genome Engineering

Agrobacterium tumefaciens, the causative agent of crown gall disease, has been repurposed as a premier vector for plant transformation. Its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid-derived T-DNA transfer mechanism represents a natural genetic engineering process. This whitepaper deconstructs this mechanism in depth, framing it within the context of delivering CRISPR-Cas9 components for advanced genome editing research. Understanding this natural process is critical for optimizing its application in creating precise genetic modifications in plants and other eukaryotic cells, with direct implications for agricultural biotechnology and drug development.

The T-DNA transfer system is a highly sophisticated interkingdom DNA delivery mechanism. For contemporary researchers, it provides a proven chassis for delivering multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 constructs, base editors, and prime editors into plant cells. The system’s ability to transfer a defined DNA segment (T-DNA) from the bacterium into the host nucleus, where it integrates into the genome, mirrors the desired outcome of modern genome editing. This guide details the molecular machinery behind this process to empower its exploitation for next-generation editing tools.

Molecular Machinery of T-DNA Transfer

The transfer process is mediated by genes within the Virulence (Vir) region of the Ti plasmid and chromosomal genes, activated by plant-derived signals.

Key Virulence Proteins and Their Functions

The following table summarizes the core Vir proteins involved in T-DNA processing and transfer.

Table 1: Core Virulence (Vir) Proteins and Functions

| Protein | Primary Function | Quantitative Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VirA/VirG | Two-component signal transduction system. VirA (sensor kinase) perceives signals (e.g., phenolics, sugars, low pH) and phosphorylates VirG (response regulator), which activates transcription of other vir genes. | VirA detects acetosyringone at nanomolar concentrations (≈50 nM). Optimal induction occurs at pH 5.0–5.5. |

| VirD1/VirD2 | Endonuclease complex. VirD2 introduces site-specific nicks at the 25-bp T-DNA border sequences. VirD1 is a topoisomerase-like accessory protein. | Nicking occurs at the bottom strand of each border repeat. VirD2 remains covalently bound to the 5' end of the single-stranded T-DNA (T-strand) via a tyrosine residue. |

| VirE2 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein. Coats the T-strand in the plant cytoplasm, protecting it from nucleases and facilitating nuclear import. | VirE2 binds ssDNA non-specifically and cooperatively. A single VirE2 monomer covers ≈30 nucleotides. |

| VirE1 | Chaperone for VirE2. Keeps VirE2 inactive in the bacterial cell, preventing premature binding to ssDNA. | VirE1-VirE2 complex formation is essential for VirE2 stability and transport. |

| VirB1-VirB11, VirD4 | Form the Type IV Secretion System (T4SS), a transmembrane pilus structure that transports the T-strand/VirD2/VirE2 complex into the host cell. | The T4SS is an 11-component (VirB1-B11, VirD4) ATP-dependent transporter. VirD4 is the "coupling protein" that recruits the T-complex. |

| VirF | Host-range factor. Ubiquitin ligase that targets host proteins for degradation, facilitating T-DNA integration. | More critical for transformation of certain plant families (e.g., Nicotiana). |

T-Complex Formation and Transport

The process initiates with VirD1/D2-mediated nicking at the right border (RB) and left border (LB), generating a single-stranded T-DNA molecule (T-strand). The VirD2 protein remains attached to its 5' end. The T-strand-VirD2 complex, along with VirE2 (exported separately), forms the mature T-complex within the plant cell.

Diagram 1: Induction and T-complex Formation

Experimental Protocols for Studying T-DNA Transfer

These protocols are foundational for researchers validating and optimizing the system for CRISPR delivery.

Protocol: β-Glucuronidase (GUS) Reporter Assay forvirGene Induction

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the induction of the vir genes in response to specific plant signals. Materials: A. tumefaciens strain carrying a vir promoter (e.g., virB or virE) fused to the uidA (GUS) reporter gene, induction medium (e.g., AB minimal medium at pH 5.5), acetosyringone stock solution (100 mM in DMSO), X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronic acid) substrate buffer. Procedure:

- Grow Agrobacterium to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5-0.8) in rich medium.

- Wash cells twice with induction medium to remove nutrients.

- Resuspend to OD600 = 0.5 in induction medium ± inducer (e.g., 100 µM acetosyringone).

- Incubate with shaking (200 rpm) at 20-25°C (optimal for vir induction) for 12-24 hours.

- Harvest cells. Perform GUS assay: Add cells to substrate buffer containing 1 mM X-Gluc. Incubate at 37°C for 1-4 hours or until blue color develops.

- Quantify: Visually assess blue color intensity or quantify enzymatically using a spectrophotometer (measure A415 after cleavage of p-nitrophenyl β-D-glucuronide). Key Controls: Include a non-induced control (-AS) and a strain with a constitutive promoter driving GUS.

Protocol: T-DNA Border Nicking Assay (In Vitro)

Purpose: To demonstrate the specific endonuclease activity of the VirD1/VirD2 complex on T-DNA border sequences. Materials: Purified His-tagged VirD1 and VirD2 proteins, supercoiled plasmid DNA containing a T-DNA border repeat (25 bp consensus), reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT), Proteinase K, agarose gel electrophoresis equipment. Procedure:

- Set up a 20 µL reaction containing 500 ng of supercoiled plasmid, 50-100 nM each VirD1/VirD2, and 1x reaction buffer.

- Incubate at 30°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Stop the reaction by adding Proteinase K (0.1 mg/mL) and SDS (0.1%) and incubating at 55°C for 15 min to remove proteins.

- Analyze DNA products by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Expected Result: Supercoiled plasmid (fastest migrating) will be converted to nicked open circular (slower migrating) and possibly linear form if two nicks occur. A control plasmid without the border sequence should remain supercoiled.

Diagram 2: vir Gene Induction Assay Workflow

Integration with CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Systems

The modern "agroinfiltration" and stable transformation protocols rely entirely on the native T-DNA transfer mechanism.

Table 2: Key Components of a CRISPR-Cas9 Binary Vector for Agrobacterium

| Component | Function in Editing | Replacement/Use of Native T-DNA System |

|---|---|---|

| T-DNA Borders (RB/LB) | Define the DNA segment to be transferred. | Directly uses the native 25-bp border sequences. |

| Cas9 Gene | Encodes the DNA endonuclease. | Inserted between T-DNA borders. Often codon-optimized for plants and driven by a plant promoter (e.g., 35S, Ubi). |

| sgRNA(s) | Guides Cas9 to target genomic locus. | Inserted between borders. Driven by Pol III promoter (e.g., U6, U3). |

| Plant Selectable Marker | Selects transformed plant cells (e.g., hygromycin, kanamycin resistance). | Inserted between borders. Replaces the oncogenes of the native T-DNA. |

| Vir Helper Plasmid | Provides Vir proteins in trans for T-DNA transfer. | A "disarmed" Ti plasmid (lacking T-DNA but with entire vir region) or a smaller "vir helper" plasmid is used in the Agrobacterium strain. |

Protocol: Agrobacterium-mediated Stable Plant Transformation (Leaf Disk) for CRISPR-Cas9 Purpose: To generate stably transgenic and edited plants.

- Vector Construction: Clone CRISPR-Cas9 expression cassette(s) into a binary vector between T-DNA borders.

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Transform the binary vector into a disarmed A. tumefaciens strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101). Grow a colony in selective medium, then subculture in induction medium with acetosyringone.

- Plant Material: Surface-sterilize and prepare leaf disks or explants from the target plant species.

- Co-cultivation: Immerse explants in the Agrobacterium suspension for 10-30 minutes, blot dry, and co-cultivate on solid medium for 2-3 days in the dark.

- Selection & Regeneration: Transfer explants to selection medium containing antibiotics to kill Agrobacterium and select for transformed plant cells (based on the T-DNA marker) and hormones to induce shoot formation.

- Rooting & Screening: Regenerated shoots are transferred to rooting medium. Genomic DNA from resulting plants is PCR-screened for T-DNA presence and sequenced for target site edits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for T-DNA/CRISPR-Agrobacterium Research

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Disarmed Agrobacterium Strains (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101, EHA105) | Various culture collections (e.g., NCPPB, lab stocks). | Provide the Vir machinery in trans for T-DNA transfer from binary vectors. Different strains have varying host ranges and transformation efficiencies. |

| Binary Vector Systems (e.g., pCAMBIA, pGreen, pCAS series) | Addgene, CAMBIA, commercial suppliers. | Modular plasmids containing T-DNA borders, multiple cloning sites, and selection markers for plants and bacteria. Essential for building CRISPR constructs. |

| Acetosyringone | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher, Cayman Chemical. | Phenolic compound used to induce the vir gene region, critical for maximizing T-DNA transfer efficiency during co-cultivation. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media (MS, B5 basal salts) | PhytoTechnology Labs, Duchefa Biochemie, Sigma-Aldrich. | Formulated media for growth, co-cultivation, selection, and regeneration of plant explants during transformation. |

| Selection Antibiotics (e.g., Kanamycin, Hygromycin B) | Various life science suppliers. | Used in plant culture media to select cells that have integrated the T-DNA (carrying the resistance gene). |

| GUS/Luciferase Reporter Assay Kits | Thermo Fisher, Promega, GoldBio. | For quantifying vir gene induction or transient/stable transformation efficiency via reporter genes encoded within the T-DNA. |

| T-DNA Border Oligonucleotides & Cloning Kits | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), NEB. | For constructing and verifying binary vectors. Kits for Golden Gate or Gibson assembly are crucial for modular CRISPR multiplexing. |

| Cas9-specific Antibodies & PCR-based Edit Detection Kits | Various suppliers (e.g., Diagenode, NEB for antibodies; Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition - TIDE analysis web tool). | For verifying Cas9 protein expression in transformed tissues and characterizing the mutation profiles at target genomic loci. |

Within the framework of developing robust Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 systems for plant genome editing research, the selection and optimization of molecular components are paramount. This technical guide details the core considerations for designing single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) and selecting appropriate Cas9 variants for delivery via Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA. The integration of these components into binary vectors, followed by stable transformation, enables precise genomic modifications for both fundamental research and trait development.

gRNA Design for Plant Genome Editing

Effective sgRNA design maximizes on-target activity and minimizes off-target effects. The process involves both sequence selection and expression cassette engineering suitable for Agrobacterium T-DNA integration.

Key Design Parameters

Target Sequence Selection:

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): For standard Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', located immediately 3' of the target DNA strand.

- Protospacer Length: Typically 20 nucleotides upstream of the PAM.

- GC Content: Optimal between 40-60%. Higher GC content can increase stability but may reduce efficiency if too high.

- Specificity: The seed region (8-12 bases proximal to the PAM) must be unique within the genome to minimize off-target cleavage.

- Positioning: For gene knockouts, target exons near the 5' end of the coding sequence to promote frameshifts and early stop codons.

sgRNA Expression Architecture: In plants, sgRNAs are commonly expressed via RNA polymerase III promoters (e.g., AtU6, OsU6) due to their precise transcription initiation and termination. The sgRNA scaffold must maintain the correct secondary structure for Cas9 binding.

Quantitative Guidelines for gRNA Design

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Optimal Plant gRNA Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Protospacer Length | 20 bp | Standard length for SpCas9 recognition and binding. |

| GC Content | 40% - 60% | Balances stability and efficiency; <20% or >80% often reduces activity. |

| Off-target Mismatch Tolerance | ≤3 mismatches in seed region | Predicts high specificity; tools like CRISPR-P or CHOPCHOP assess this. |

| Target Site Position (for KO) | Within first 50-75% of coding sequence | Maximizes probability of disruptive frameshift mutation. |

| Poly-T Tracts | Avoid 4+ consecutive T's | Can act as premature termination signal for Pol III promoters. |

Experimental Protocol: In Silico gRNA Design and Selection

Methodology:

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the FASTA format genomic sequence of the target gene from databases like Phytozome or Ensembl Plants.

- PAM Identification: Scan both DNA strands for all 5'-NGG-3' sequences within the target region.

- Candidate Listing: Extract 20 nucleotides immediately 5' of each PAM as candidate protospacers.

- Specificity Check: Input each candidate into a plant-specific gRNA design tool (e.g., CRISPR-P 2.0, CHOPCHOP). Use the tool’s genome-wide alignment to identify potential off-target sites. Rank candidates by the number of off-targets, prioritizing those with zero or minimal off-targets, especially in coding regions.

- Efficiency Prediction: Use the tool's scoring algorithm (which factors in GC content, sequence features, etc.) to predict on-target efficiency. Select the top 2-3 candidates with high predicted efficiency and high specificity.

- Final Selection: Verify the uniqueness of the selected sequence by performing a BLASTN search against the host plant genome.

Cas9 Variants for Agrobacterium Delivery

The choice of Cas9 variant influences editing efficiency, specificity, and compatibility with Agrobacterium delivery. The coding sequence must be codon-optimized for the host plant and placed under a strong constitutive or tissue-specific plant promoter (e.g., CaMV 35S, Ubiquitin).

Commonly Used Variants

- Standard SpCas9: The wild-type nuclease, effective but with potential for off-target effects. Size (~4.2 kb) is a consideration for vector capacity.

- High-Fidelity Variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9(1.1)): Engineered to reduce non-specific DNA binding, significantly lowering off-target activity while retaining robust on-target cleavage.

- Cas9 Nickases (D10A or H840A): Generate single-strand breaks (nicks). Paired nickases with offset sgRNAs create staggered double-strand breaks, dramatically increasing specificity.

- Base Editors (BE, e.g., BE3): Fusions of catalytically impaired Cas9 (nCas9, D10A) with a deaminase enzyme. Enable direct, template-free conversion of C•G to T•A (or A•T to G•C) without creating double-strand breaks, ideal for precise point mutations.

- VirD2-Cas9 Fusions: Experimental fusions of Cas9 to Agrobacterium VirD2 protein. Exploits the natural T-DNA integration machinery, potentially guiding Cas9 to the T-DNA integration complex to edit at the site of insertion.

Quantitative Comparison of Cas9 Variants

Table 2: Comparison of Key Cas9 Variants for Plant Editing via Agrobacterium

| Variant | Key Feature | Typical On-Target Efficiency | Relative Specificity | Primary Application | Size Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (WT) | Double-strand break (DSB) inducer | High (Varies by target) | Standard | Gene knockouts, large deletions | ~4.2 kb (Reference) |

| SpCas9-HF1 | Reduced non-specific binding | Slightly reduced vs. WT | Very High | High-fidelity knockouts | Similar to WT |

| nCas9 (D10A) | Single-strand break (nick) inducer | N/A (paired use) | Extremely High (paired) | Paired nicking for precise deletions | Similar to WT |

| BE3 (nCas9-D10A-cytidine deaminase) | C•G to T•A base editing | Moderate to High (for conversion) | High (no DSB) | Point mutations, precise amino acid changes | Larger (~5.6 kb) |

| VirD2-Cas9 Fusion | Targeted to T-DNA complex | Under investigation | Potentially high at T-DNA locus | Editing at site of T-DNA integration | Larger than WT |

Experimental Protocol: Assembling CRISPR-Cas9 Constructs in a Binary Vector

Objective: Clone selected sgRNA(s) and Cas9 variant expression cassettes into a T-DNA binary vector for Agrobacterium transformation.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Methodology:

- sgRNA Oligo Annealing: Design forward and reverse oligonucleotides corresponding to the 20-nt protospacer, with 5' overhangs compatible with your chosen cloning site (e.g., BsaI for Golden Gate).

- Resuspend oligos to 100 µM. Mix 1 µL of each, 1 µL of 10x T4 Ligation Buffer, and 7 µL nuclease-free water.

- Heat to 95°C for 5 minutes, then cool slowly to 25°C (ramp rate 0.1°C/sec) in a thermocycler.

- Golden Gate Assembly (Example):

- Set up a reaction: 50 ng linearized destination binary vector, 1 µL annealed oligo duplex (diluted 1:10), 1 µL Cas9 expression module entry vector, 1 µL of BsaI-HFv2, 1 µL T4 DNA Ligase, 2 µL 10x T4 Ligase Buffer, nuclease-free water to 20 µL.

- Cycle in a thermocycler: (37°C for 2 min, 16°C for 5 min) x 30 cycles, then 50°C for 5 min, 80°C for 5 min.

- Transformation and Verification:

- Transform 2 µL of assembly reaction into competent E. coli cells via heat shock or electroporation. Plate on appropriate antibiotics.

- Screen colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest. Validate final plasmid by Sanger sequencing across all cloned junctions.

- Agrobacterium Transformation:

- Introduce the verified binary vector into disarmed Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., GV3101, EHA105) via electroporation or freeze-thaw method.

- Select on plates with antibiotics specific for the bacterial strain and the binary vector.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: gRNA Design and Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: Generic Binary Vector Map for Agrobacterium Delivery

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Plant-Specific gRNA Design Tool (CRISPR-P 2.0) | Web tool for designing and scoring sgRNAs with plant genome databases. |

| Binary Vector System (e.g., pCambia, pCAMBIA1300, pHSE401) | Contains T-DNA borders, plant and bacterial selectable markers, and multiple cloning sites. |

| Golden Gate MoClo-Compatible Vectors | Modular cloning system for efficient, one-pot assembly of multiple expression cassettes. |

| BsaI-HFv2 Restriction Enzyme | Type IIS enzyme used in Golden Gate assembly to create unique, non-palindromic overhangs. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments with compatible cohesive ends during assembly. |

| Chemically Competent E. coli (DH5α, TOP10) | For plasmid propagation and cloning intermediate steps. |

| Electrocompetent Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101) | Strain for transforming plant cells via floral dip or tissue culture. |

| Plant Codon-Optimized Cas9 Gene | Synthetic gene with altered codon usage to maximize expression in plants (e.g., Arabidopsis, rice). |

| U6 snRNA Promoter Clones (AtU6-26, OsU6) | Source of Pol III promoters for driving sgRNA expression in dicots or monocots. |

| Sanger Sequencing Primers (e.g., 35S-F, T7 Term-R) | Verify sequence integrity of assembled T-DNA constructs. |

The development of efficient plant genome editing tools is a cornerstone of modern agricultural and pharmaceutical research. Within the framework of a broader thesis on Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 systems, the choice of binary vector backbone is critical. This guide provides an in-depth analysis of the two primary plasmid systems derived from Agrobacterium tumefaciens and A. rhizogenes—the Ti (Tumor-inducing) and Ri (Root-inducing) plasmids. We dissect their anatomy, compare their functional components, and detail protocols for engineering them into effective binary vectors for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 constructs into plant genomes.

Anatomical Comparison: Disarmed Ti vs. Ri Plasmid Backbones

The native Ti and Ri plasmids cause crown gall and hairy root diseases, respectively. For safe plant biotech use, they are "disarmed" by removing oncogenes (iaaM, iaaH, ipt for Ti; rol genes for Ri) while retaining essential DNA transfer functions.

Table 1: Core Components of Disarmed Binary Vector Systems

| Component | Function in T-DNA Transfer | Ti Plasmid (e.g., pTiBo542) | Ri Plasmid (e.g., pRiA4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virulence (Vir) Region | cis-acting proteins for T-DNA processing/transfer | ~25 kb, 7 essential operons (virA-G) | Homologous, functional compatibility with Ti Vir |

| T-DNA Borders | 25-bp direct repeats; recognition site for VirD2 | Left Border (LB), Right Border (RB) | LB, RB (often multiple in native Ri) |

| Origin of Replication (ori) | Plasmid maintenance in Agrobacterium | oriV (often RK2-based for broad host) | oriV (often pRi-specific) |

| Conjugative Transfer (tra) Region | Plasmid conjugation | Often present, can be removed | Often present |

| Selectable Marker | Bacterial selection | Spectinomycin, Kanamycin resistance | Kanamycin, Tetracycline resistance |

| Disarmed T-DNA Region | Replaced with MCS for gene of interest | Oncogenes removed, "empty" for user insert | rol genes removed, "empty" for user insert |

| Overdrive Sequence | Enhances VirD2 binding, increases transfer | Present adjacent to RB | Often absent or less effective |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison for CRISPR Assembly Applications

| Parameter | Ti-based Binary Vector | Ri-based Binary Vector | Implication for CRISPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical T-DNA Insert Size Limit | ~40 kb | ~20 kb | Both sufficient for Cas9+gRNA(s). Ti preferred for large multiplex arrays. |

| Transformation Efficiency (Model Plants) | High (e.g., 80-90% in Nicotiana) | Moderate to High | Ti often yields higher primary transformants. |

| Regeneration Ease | Standard, from callus | Can be challenging; prone to hairy root morphology | Ti vectors preferred for stable transformants. |

| Expression Stability | High | Can exhibit gene silencing | Ti offers more predictable CRISPR component expression. |

| Typical Cloning Strategy | Gateway, Golden Gate, standard MCS | Standard MCS | Both compatible with modular CRISPR assembly kits. |

Protocol: Engineering a CRISPR-Cas9 Construct into a Binary Vector

This protocol assumes a disarmed binary vector (e.g., pCAMBIA1300 from Ti or pRiA4::GUS) and an assembled CRISPR expression cassette (Plant promoter::Cas9, U6/Pol III promoter::gRNA).

Materials & Reagents:

- Disarmed binary vector (50 ng/µL)

- Purified CRISPR insert fragment

- Restriction enzymes (e.g., AscI, PacI) or Gateway BP/LR Clonase II

- T4 DNA Ligase

- Chemically competent E. coli (e.g., DH5α)

- Electrocompetent Agrobacterium tumefaciens (e.g., strain LBA4404, GV3101)

- Selection antibiotics (Kanamycin, Spectinomycin, Rifampicin)

Procedure:

- Linearization: Digest 2 µg of binary vector with appropriate enzymes to remove the placeholder fragment in the T-DNA region. Purify using a gel extraction kit.

- Ligation: Mix the linearized vector with a 3:1 molar ratio of the CRISPR insert fragment. Use T4 DNA Ligase (1 hour, 25°C). For Gateway cloning, follow the manufacturer's protocol for the LR reaction.

- E. coli Transformation: Transform ligation mix into competent E. coli. Select on LB agar with the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., Kanamycin 50 mg/L). Isolate plasmid DNA from colonies and confirm by colony PCR and Sanger sequencing.

- Agrobacterium Transformation (Freeze-Thaw Method): a. Aliquot 100 µL of electrocompetent Agrobacterium (e.g., GV3101) on ice. b. Add ~100 ng of verified plasmid DNA. Mix gently. c. Freeze in liquid nitrogen for 1 minute, then thaw at 37°C for 5 minutes. d. Add 1 mL of YEP broth and incubate at 28°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 2-3 hours. e. Plate on YEP agar with vector-specific antibiotics and Agrobacterium strain-specific Rifampicin (often 50 mg/L). Incubate at 28°C for 2 days.

- Validation: Ispect colonies and perform PCR to confirm the presence of the binary vector.

Protocol: Plant Transformation viaAgrobacterium(Leaf Disc -Nicotiana tabacum)

Materials: Sterilized leaf discs, Agrobacterium culture carrying CRISPR binary vector, Co-cultivation media (MS + 2 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA), Selection media (MS + antibiotics + 250 mg/L Cefotaxime), Regeneration media.

Procedure:

- Grow Agrobacterium overnight in YEP with antibiotics to OD600 ~0.8. Centrifuge and resuspend in MS liquid medium.

- Dip sterilized leaf discs into bacterial suspension for 10 minutes. Blot dry and place on co-cultivation media in the dark at 25°C for 48 hours.

- Transfer discs to selection media containing antibiotics to kill Agrobacterium (Cefotaxime) and select for transformed plant cells (e.g., Hygromycin). Subculture every 2 weeks.

- Once shoots develop (3-4 weeks), transfer to rooting media.

- After root development, transfer plantlets to soil and genotype by PCR and sequencing to confirm CRISPR-induced edits.

Visualization: Binary Vector System & T-DNA Transfer Workflow

Diagram 1: CRISPR binary vector assembly and T-DNA delivery path.

Diagram 2: Vir gene activation and T-strand production pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Binary Vector CRISPR Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Disarmed Binary Vectors (pCAMBIA, pGreen, pMDC) | Addgene, Cambia, TAIR | Backbone providing T-DNA borders, plant selection marker, and bacterial replication origin. |

| Modular CRISPR Assembly Kits (Golden Gate MoClo) | Addgene, Kit #1000000044 | Enables rapid, standardized assembly of multiple gRNA expression cassettes into binary vectors. |

| Agrobacterium Strains (LBA4404, GV3101, EHA105) | Various Culture Collections | Engineered disarmed strains harboring a helper Ti plasmid (with vir genes) for T-DNA transfer. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media (MS Basal Salts) | PhytoTech Labs, Sigma-Aldrich | Provides nutrients and hormones for in vitro plant growth, selection, and regeneration. |

| Selection Antibiotics (Hygromycin, Kanamycin) | Thermo Fisher, GoldBio | Selective agents in media to eliminate non-transformed plant tissues or bacteria. |

| PCR Enzymes for Genotyping (Phire, GoTaq) | NEB, Promega | Amplifies genomic regions flanking CRISPR target sites to screen for edits via sequencing or assay. |

| Restriction Enzymes (Type IIs, e.g., BsaI) | NEB, Thermo Scientific | Essential for Golden Gate assembly and linearization of vector backbones. |

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation remains the preferred method for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 components for plant genome editing due to its ability to generate stable, low-copy-number integration events. Understanding host range specificity is critical for designing effective transformation strategies. This whitepaper, framed within the broader thesis of deploying Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 systems, details the plant species amenable to this transformation and the underlying molecular mechanisms.

The Molecular Basis of Host Range

Agrobacterium tumefaciens transfers a segment of DNA (T-DNA) from its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant genome. This process is governed by a series of molecular signals and virulence (vir) genes. Host specificity is determined by:

- Chemoattraction and Attachment: Recognition of specific phenolic compounds (e.g., acetosyringone) released by wounded plants via the VirA/VirG two-component system.

- T-DNA Processing: The virD1/virD2 genes excise the T-DNA.

- Effector Protein Function: VirE2, VirF, and others interact with host proteins to facilitate T-DNA nuclear import and integration.

- Plant Defense Response: The plant's innate immune system can limit transformation success.

Spectrum of Amenable Plant Species

Based on recent literature and databases, amenable species are categorized below. Success is often genotype-dependent within a species.

Table 1: Model and Major Crop Species with Established Agrobacterium Transformation Protocols

| Species | Common Name | Family | Typical Efficiency (T0) | Key Genotype/Variety | CRISPR-Cas9 Demonstrated? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana tabacum | Tobacco | Solanaceae | >80% (leaf disc) | SR1, Petit Havana | Yes (Extensively) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Thale Cress | Brassicaceae | ~2-5% (floral dip) | Col-0 | Yes (Standard) |

| Oryza sativa | Rice | Poaceae | 20-40% (callus) | Nipponbare, Kitake | Yes (Routine) |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Tomato | Solanaceae | 15-30% (cotyledon) | Micro-Tom, Moneymaker | Yes |

| Solanum tuberosum | Potato | Solanaceae | 10-25% (internode) | Desiree, Russet | Yes |

| Zea mays | Maize | Poaceae | 5-15% (immature embryo) | B104, Hi-II | Yes |

| Glycine max | Soybean | Fabaceae | 5-20% (cotyledonary node) | Williams 82 | Yes |

| Triticum aestivum | Wheat | Poaceae | 5-15% (immature embryo) | Fielder, Bobwhite | Yes |

Table 2: Recalcitrant and Emerging Species

| Species | Common Name | Family | Status & Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinus taeda | Loblolly Pine | Pinaceae | Highly recalcitrant. Poor T-DNA integration, strong defense response. |

| Vitis vinifera | Grapevine | Vitaceae | Possible but inefficient. Genotype-dependent, requires vir gene inducers. |

| Coffea arabica | Coffee | Rubiaceae | Emerging protocols. Low regeneration efficiency post-transformation. |

| Many Monocots (e.g., Barley, Oat) | - | Poaceae | Historically difficult; improved using super-virulent strains (e.g., AGL1) and additives. |

Key Experimental Protocol: Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation of Rice for CRISPR-Cas9

This detailed protocol exemplifies the workflow for a major monocot crop.

1. Vector Construction:

- Clone a gRNA expression cassette (driven by a U3/U6 pol III promoter) and a Cas9 expression cassette (driven by a maize Ubi promoter) into the T-DNA region of a binary vector (e.g., pCAMBIA1300).

- Transform the recombinant binary vector into an Agrobacterium strain (e.g., EHA105, LBA4404).

2. Preparation of Explant:

- Surface sterilize mature rice seeds.

- Induce callus formation on N6D medium (N6 salts, 2,4-D) for 3-4 weeks. Select embryogenic, type I calli.

3. Co-cultivation:

- Suspend log-phase Agrobacterium (OD600 ~0.8-1.0) in AAM or MS liquid medium with 100 µM acetosyringone.

- Immerse calli in the suspension for 30 minutes. Blot dry and co-cultivate on filter paper overlaid on co-cultivation medium (with acetosyringone) for 2-3 days in the dark at 22-25°C.

4. Selection & Regeneration:

- Transfer calli to resting medium (with antibiotics to suppress Agrobacterium, no selection) for 5-7 days.

- Transfer to selection medium (containing hygromycin or bialaphos) for 2-3 weeks. Subculture surviving calli every 2 weeks.

- Move antibiotic-resistant calli to pre-regeneration and then regeneration medium to induce shoot and root development.

5. Molecular Analysis:

- Perform PCR on genomic DNA from putative transgenic plants (T0) to confirm the presence of cas9 and hpt transgenes.

- Use T7E1 or SURVEYOR assay, followed by Sanger sequencing, to verify target site mutations.

Key Signaling Pathway in Host Recognition

The initial step determining host compatibility is the sensing of wound signals by Agrobacterium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Product/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Super-virulent A. tumefaciens Strain | Contains a Ti plasmid with a constitutively active virG gene (e.g., virGN54D), enhancing T-DNA transfer in recalcitrant plants. | Strain AGL1, EHA105 |

| Binary Vector System | A T-DNA vector with plant selection marker, CRISPR-Cas9 expression units, and borders compatible with the strain. | pCambia, pGreen, pDIRECT vectors |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces the vir gene region. Critical for co-cultivation, especially for monocots. | Sigma-Aldrich, D134406 |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Basal salts and vitamins for explant growth, callus induction, and regeneration (e.g., MS, N6). | PhytoTech Labs |

| Selection Agent | Herbicide or antibiotic for selecting transformed tissue (e.g., hygromycin, glufosinate). | Gold Biotechnology |

| PCR Mix for Plant Genotyping | High-fidelity polymerase capable of amplifying GC-rich plant genomic DNA. | NEB Q5 Hot Start, Phire Plant Direct PCR Kit |

| Mutation Detection Kit | For initial screening of CRISPR-induced indels. | IDT Alt-R Genome Editing Detection Kit (T7E1) |

| Silwet L-77 | Surfactant used in floral dip transformation of Arabidopsis and to enhance infiltration in other species. | Lehle Seeds |

Strategies for Expanding Host Range

To extend transformation to non-host or recalcitrant species within a CRISPR research paradigm:

- Use of Hyper-virulent Strains: Employ strains like AGL1 (pTiBo542) or LBA4404 harboring a "super-virulent" helper plasmid.

- Chemical Enhancement: Addition of acetosyringone, cytokinins, or antioxidants (e.g., ascorbic acid) during co-cultivation.

- Host Gene Co-transformation: Transiently express Arabidopsis genes known to facilitate transformation (e.g., VIP1, histones) alongside CRISPR components.

- Nanoparticle-Assisted Delivery: Pre-treat tissue with pectinase or cellulose-degrading nanoparticles to weaken cell walls prior to Agrobacterium infection.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a soil-borne phytopathogen, has evolved to transfer a segment of its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid DNA (T-DNA) into plant cells, causing crown gall disease. The molecular dissection of this natural genetic engineering system revealed the essential components: the vir (virulence) region, the T-DNA borders (left and right repeats), and the chromosomal chv genes. Disarming this pathogen by deleting oncogenes from the T-DNA while retaining its DNA transfer machinery forms the cornerstone of its biotechnological application. This foundational technology is now pivotal for the precise delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components for advanced genome editing research.

Core Molecular Machinery and Signaling Pathways

The transformation process is a sophisticated, multi-step signaling cascade.

Diagram 1: Agrobacterium Transformation Signaling & Transfer Pathway

Evolution of Vector Systems: From Plasmids to Binary Vectors

The development of transformation vectors progressed from large, intact Ti plasmids to streamlined binary and superbinary systems.

Table 1: Evolution of Agrobacterium Vector Systems

| Vector Type | Key Components (Plasmids) | T-DNA Size Limit | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-integrate | Disarmed Ti plasmid + Intermediate vector | ~50 kb | Stable integration | Complex recombination, lower efficiency |

| Binary | Helper Ti plasmid (Vir genes) + Binary vector (T-DNA) | ~150 kb* | Simple, versatile, high copy in E. coli | Vir gene efficacy strain-dependent |

| Superbinary | Helper with extra vir genes (e.g., pTiBo542 virB, virC, virG) + Binary vector | ~150 kb* | Enhanced T-DNA transfer, broad host range | More complex helper plasmid |

| Miniature | Helper + Binary with minimal backbone ("Micro-T") | N/A | Reduced extraneous DNA, higher efficiency for large constructs | Specialized cloning required |

*Practical limit; theoretical limit is higher.

Agrobacterium-Delivered CRISPR-Cas9 Systems: Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Construction of a Binary Vector for CRISPR-Cas9 Expression in Plants

Objective: Assemble a T-DNA containing a plant codon-optimized Cas9 nuclease and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) expression unit.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Method:

- sgRNA Cloning:

- Design a 20-nt target sequence complementary to your genomic target, preceding a 5'-NGG-3' PAM.

- Synthesize two complementary oligonucleotides containing the target sequence with 5' overhangs compatible with your chosen sgRNA scaffold cloning site (e.g., BsaI sites for Golden Gate assembly into pU6 or pU3 promoter vectors).

- Anneal oligos and perform a Golden Gate assembly or standard restriction-ligation into the pre-digested sgRNA expression cassette vector.

Binary Vector Assembly:

- Using a multisite Gateway LR reaction or a advanced Golden Gate assembly (e.g., MoClo system): a. Mix the entry clones: pENTR-Cas9 (e.g., SpCas9 with plant nuclear localization signals), pENTR-sgRNA (from step 1), and pENTR-PlantSelectableMarker (e.g., bar or hptII). b. Add the destination binary vector (e.g., pB7m34GW, pCAMBIA series) and LR Clonase II enzyme mix. c. Incubate at 25°C for 1-16 hours. d. Transform the reaction into chemically competent E. coli, select on appropriate antibiotics.

Validation:

- Isolate plasmid DNA from colonies.

- Verify assembly by colony PCR and diagnostic restriction digest.

- Confirm the final T-DNA sequence by Sanger sequencing across all junctions.

Protocol: Agrobacterium Transformation and Plant Transformation (Floral Dip)

Objective: Introduce the binary vector into Agrobacterium and transform Arabidopsis thaliana.

Method:

- Agrobacterium Electroporation:

- Thaw electrocompetent cells of a suitable Agrobacterium strain (e.g., GV3101::pMP90) on ice.

- Add 50-100 ng of the validated binary vector plasmid to 50 µL of cells in a pre-chilled electroporation cuvette (1 mm gap).

- Electroporate at 1.8 kV, 200 Ω, 25 µF.

- Immediately add 950 µL of SOC or LB medium and incubate at 28°C with shaking (220 rpm) for 2-3 hours.

- Plate on LB agar with selective antibiotics for both the Agrobacterium chromosomal marker and the binary vector (e.g., rifampicin + spectinomycin). Incubate at 28°C for 2 days.

Preparation for Floral Dip:

- Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL of LB with antibiotics. Grow overnight at 28°C, shaking.

- Subculture 1 mL into 500 mL of fresh transformation medium (5% sucrose, 1/2x Murashige and Skoog salts, 0.044 µM benzylaminopurine, pH 5.7) with antibiotics and 200 µM acetosyringone. Grow to an OD600 of ~1.5.

- Centrifuge cells at 5000 x g for 15 min at room temperature. Resuspend pellet in 500 mL of dipping medium (5% sucrose, 0.05% Silwet L-77).

Arabidopsis Floral Dip:

- Immerse the inflorescences of healthy, 4-6 week old Arabidopsis plants into the Agrobacterium suspension for 30 seconds, with gentle agitation.

- Lay plants horizontally in a tray, cover with transparent film to maintain humidity for 24 hours.

- Return plants to upright position and grow normally until seeds mature (~6 weeks).

Selection of Transformants:

- Harvest seeds (T1 generation). Surface sterilize and sow on plates or soil saturated with the appropriate selection agent (e.g., glufosinate ammonium or hygromycin B).

- Resistant seedlings (T1 transformants) are screened by PCR for the presence of the transgene and later analyzed for CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency via T7 Endonuclease I assay or sequencing of the target locus.

Quantitative Data: Efficiency and Applications

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Agrobacterium-Delivered CRISPR-Cas9 in Model Plants

| Plant Species | Transformation Method | Typical T1 Transformation Efficiency* | Reported Mutation Efficiency (Biallelic/Homozygous) | Key References (Recent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Floral Dip | 1-5% | 10-60% | Tsutsui & Higashiyama (2017), Nature Protocols |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | Leaf Disk Infiltration | ~90% (transient) | 70-95% (transient) | LeBlanc et al. (2018), Plant Physiol |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Callus Cocultivation | 30-80% (stable calli) | 20-90% | Minkenberg et al. (2017), Nucleic Acids Res |

| Tomato (Solanum lycop.) | Cotyledon Cocultivation | 20-60% | 50-80% | Van Eck et al. (2019), Plant Cell Tiss Org Cult |

| Maize (Zea mays) | Immature Embryo | 5-40% | 10-50% | Char et al. (2020), Plant Biotechnol J |

Efficiency defined as percentage of treated explants/plants yielding resistant transformants. *Varies significantly by target locus, guide RNA design, and Cas9 expression level.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector System | Backbone for T-DNA cloning; contains LB/RB, plant selectable marker, bacterial origin. | pCAMBIA1300, pB7m34GW, pGreenII, pYLCRISPR/Cas9 series |

| Helper Ti Plasmid | Provides vir genes in trans for T-DNA processing/transfer. | pMP90 (in GV3101), pEHA105 (in EHA105), pTiBo542 (in AGL1) |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Disarmed, helper plasmid-containing strain for plant transformation. | GV3101, LBA4404, EHA105, AGL1 |

| Plant Codon-Optimized SpCas9 | Nuclease for creating double-strand breaks; entry clone for assembly. | pHEE401, pCBC-DT1T2, Addgene #72200 series |

| sgRNA Cloning Vector | Contains Pol III promoter (U6, U3) and sgRNA scaffold for easy oligo insertion. | pAtU6-sgRNA, pOsU3-sgRNA, pBUN-sgRNA |

| Gateway LR Clonase II | Enzyme mix for efficient, multi-fragment assembly into binary vectors. | Thermo Fisher, 11791020 |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces the vir gene expression cascade. | Sigma-Aldrich, D134406 |

| Silwet L-77 | Surfactant that lowers surface tension for effective tissue infiltration during floral dip. | Lehle Seeds, VIS-30 |

| Selection Antibiotics (Plant) | For in vitro selection of transformants (e.g., Hygromycin B, Glufosinate-ammonium). | Various suppliers |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Enzyme for detecting CRISPR-induced indels via mismatch cleavage assay. | NEB, M0302S |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Delivering CRISPR-Cas9 via Agrobacterium for Stable Plant Transformation

This technical guide details the construction of plant transformation vectors for Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. The process involves assembling two core components—the guide RNA (gRNA) expression cassette and the Cas9 endonuclease gene—into a binary vector backbone suitable for Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. This work is central to a thesis focused on developing efficient, multiplexed genome editing systems for crop improvement and functional genomics research.

Core Components and Their Quantitative Specifications

The selection of promoters, terminators, and resistance markers is critical for efficient expression in plant cells. The following tables summarize key quantitative data for common components.

Table 1: Promoter Efficacy for gRNA Expression in Monocots and Dicots

| Promoter | Origin | Plant Type | Relative Expression Strength* | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtU6-26 | A. thaliana | Dicots | 100% (Baseline) | gRNA expression |

| OsU3 | O. sativa | Monocots | ~95-110% | gRNA expression |

| 35S | Cauliflower Mosaic Virus | Broad | Very High | Cas9 expression |

| ZmUbi1 | Z. mays | Monocots | High, Constitutive | Cas9 expression |

*Expression strength normalized to common baseline; data derived from recent comparative studies (2023-2024).

Table 2: Common Binary Vector Backbones and Key Features

| Binary Vector | Size (kb) | Bacterial Resistance | Plant Selection | Replicon | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCAMBIA1300 | ~9.2 | Kanamycin | Hygromycin | pVS1 | High copy in E. coli |

| pGreenII | ~3.8 | Kanamycin | Variable | pSa | Small size, versatile |

| pBIN19 | ~11.8 | Kanamycin | Kanamycin | pVS1 | Classic, widely used |

| pCAS9-TPC | ~12.5 | Spectinomycin | Hygromycin | pVS1 | Pre-assembled T-DNA) |

Experimental Protocol: Golden Gate Assembly-Based Construction

This protocol describes a modular, restriction-ligation based method for assembling multiple gRNA cassettes and Cas9 into a binary vector.

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (BsaI, BbsI) | Enable scarless, directional assembly of multiple DNA fragments. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Ligates cohesive ends generated by Type IIS enzymes. |

| High-Efficiency Competent Cells (E. coli) | Essential for transforming large (>10 kb) plasmid assemblies. |

| Chemically Competent Agrobacterium (e.g., GV3101) | For final vector mobilization and plant transformation. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Selective media containing appropriate antibiotics for transgenic tissue. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Alternative cloning method for larger fragments or simple fusions. |

| Plasmid Miniprep/Midiprep Kits | For reliable purification of plasmid DNA at various scales. |

| Sanger Sequencing Primers (e.g., pVS1 rev) | For verifying the integrity of the T-DNA region in the binary vector. |

Detailed Stepwise Protocol

Part A: Preparation of Modules

- Design gRNA Sequences: Identify 20-nt target sequences preceding a 5'-NGG-3' PAM. Avoid off-targets using tools like CRISPR-P or CHOPCHOP.

- Oligonucleotide Annealing: Synthesize complementary oligos for each target, anneal them, and clone into a Level 0 gRNA entry vector (e.g., pEN-Chimera) containing a Pol III promoter (U6/U3) and terminator, flanked by BsaI sites.

- Prepare Cas9 Expression Cassette: Obtain a plant codon-optimized Cas9 gene (with intron) under a strong Pol II promoter (e.g., 2x35S or ZmUbi1) and a polyA terminator in a Level 0 vector.

Part B: Golden Gate Assembly into Binary Vector

- Set Up Reaction Mix:

- Binary vector backbone (Level 1 destination, ~50 ng)

- Level 0 gRNA module(s) (each ~20 ng)

- Level 0 Cas9 module (~30 ng)

- T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (1X final)

- ATP (1 mM final)

- BsaI-HF v2 (10 U)

- T4 DNA Ligase (400 U)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL.

- Run Thermocycler Program:

- (37°C for 5 min → 16°C for 5 min) x 25-30 cycles

- 50°C for 5 min (final digestion)

- 80°C for 5 min (enzyme heat inactivation).

- Transformation and Screening: Transform 5 µL of the reaction into competent E. coli. Screen colonies by colony PCR and restriction digest. Confirm final plasmid by sequencing across all assembly junctions and gRNA scaffolds.

Part C: Mobilization into Agrobacterium

- Introduce the verified binary plasmid into disarmed A. tumefaciens strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101) via freeze-thaw or electroporation.

- Select on plates containing appropriate antibiotics for both the binary vector and the Agrobacterium strain (e.g., rifampicin, gentamicin).

- Verify the plasmid's presence in Agrobacterium by PCR before use in plant transformation.

Visualization of Workflows and Construct Design

Diagram 1: Modular Cloning Workflow from Oligos to Binary Vector

Diagram 2: Final T-DNA Structure in Binary Vector

Within the framework of developing an Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 system for plant genome editing, selecting the optimal strain is a critical determinant of transformation efficiency and transgenic event quality. The disarmed helper strains LBA4404, GV3101, and EHA105 are among the most widely utilized, each with distinct genetic backgrounds and characteristics that influence T-DNA delivery. This guide provides a technical comparison to inform strain selection for modern CRISPR-Cas9 research.

Genetic Background and Virulence Characteristics

The efficacy of an Agrobacterium strain is primarily governed by its chromosomal background and the type of Ti plasmid it harbors.

Table 1: Core Genetic and Virulence Features

| Feature | LBA4404 | GV3101 | EHA105 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Strain | Ach5 | C58 | A281 |

| Ti Plasmid | pAL4404 (disarmed pTiAch5) | pMP90 (disarmed pTiC58) | pEHA105 (disarmed pTiBo542) |

| Virulence System | Octopine-type | Nopaline-type | Succinamopine-type (pTiBo542) |

| Chromosomal Background | Ach5 | C58 | C58 |

| Key Virulence Trait | Standard virulence | Robust, C58 background | Contains virG (N54D) mutation ("super-virulent") |

| Common Plant Applications | Monocots (rice), Dicots (tomato, tobacco) | Arabidopsis (floral dip), Dicots (tobacco, Nicotiana spp.) | "Refractory" Dicots (soybean, cotton), some Monocots |

The virG (N54D) mutation in EHA105's pTiBo542 plasmid enhances the expression of other vir genes, leading to its characterization as "super-virulent," particularly useful for difficult-to-transform species.

Quantitative Performance Data in CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery

Recent studies comparing transformation efficiency (typically measured as % of explants producing stable transgenic events or transient expression rates) highlight performance differences.

Table 2: Comparative Transformation Efficiency Data

| Strain | Target Plant Species | Efficiency Metric (CRISPR-Cas9 Context) | Key Finding (vs. Others) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LBA4404 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | ~15-25% stable transformation frequency | Reliable for standard japonica varieties. |

| GV3101 | Arabidopsis thaliana | >3% T1 positive edit rate (floral dip) | Gold standard for Arabidopsis; high transient expression in tobacco. |

| GV3101 | Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) | High transient GUS/GFP expression | Often superior for leaf disc assays. |

| EHA105 | Soybean (Glycine max) | 2-5% stable transformation frequency | Consistently outperforms LBA4404/GV3101 in "recalcitrant" crops. |

| EHA105 | Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) | 1-3% embryogenic callus transformation | Essential for achieving any edits in elite cultivars. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Comparative Strain Testing

This protocol outlines a standardized leaf disc assay for Nicotiana benthamiana to compare transient transformation efficiency between strains, a common precursor to stable transformation studies.

Materials:

- N. benthamiana plants (4-5 weeks old)

- CRISPR-Cas9 binary vectors (identical for all strains)

- Agrobacterium strains LBA4404, GV3101, EHA105

- YEP or LB media with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., Rifampicin, Kanamycin)

- Infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, 150 µM Acetosyringone, pH 5.6)

- Sterile Petri dishes, co-cultivation media (MS basal)

Procedure:

- Vector Transformation: Introduce the same CRISPR-Cas9 binary vector (e.g., pCambia-based with gRNA expression cassette) into each Agrobacterium strain via electroporation or freeze-thaw. Confirm by colony PCR.

- Culture Initiation: Inoculate a single colony for each strain into 5 mL liquid YEP with antibiotics. Grow overnight at 28°C, 220 rpm.

- Culture Induction: Dilute the overnight culture 1:50 in fresh YEP with antibiotics and grow to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.6-0.8. Pellet cells at 5000 g for 10 min.

- Resuspension: Gently resuspend the pellet in infiltration buffer to a final OD₆₀₀ of 0.5. Incubate the suspension at room temperature for 1-3 hours.

- Plant Infiltration: Using a 1 mL needleless syringe, infiltrate the bacterial suspensions into the abaxial side of fully expanded N. benthamiana leaves. Mark infiltration zones. Include infiltration buffer only as a negative control.

- Sampling & Analysis: Harvest leaf discs from infiltrated zones at 3-4 days post-infiltration (dpi).

- For transient GUS (β-glucuronidase) assay: Stain discs with X-Gluc solution and quantify blue foci.

- For transient GFP expression: Visualize under a fluorescence microscope and quantify fluorescent spots.

- For CRISPR activity: Extract genomic DNA and perform T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) or RFLP assay on the target site to measure indel formation frequency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Agrobacterium-CRISPR Work

| Item | Function in Experiment | Critical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector System (e.g., pCAMBIA, pGreen) | Carries T-DNA with CRISPR-Cas9 expression cassettes (Cas9, gRNA, plant selectable marker). | Must be compatible with Agrobacterium strains (have proper ori and virulence region). |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces the vir gene region on the Ti plasmid, activating the T-DNA transfer machinery. | Essential for transformation of most plants except Arabidopsis floral dip. |

| Antibiotics (Rifampicin, Kanamycin, Spectinomycin) | Selective agents to maintain the Agrobacterium strain (chromosomal) and the binary vector (plasmid). | Verify strain-specific resistance (e.g., GV3101 is Rif⁺, Gent⁺; EHA105 is Rif⁺). |

| Silwet L-77 (for Floral Dip) | Surfactant that lowers surface tension, enabling Agrobacterium (GV3101) suspension to infiltrate Arabidopsis floral tissues. | Used at ~0.02-0.05% for optimal efficiency without phytotoxicity. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) / RFLP Assay Kit | Enzymatic mismatch cleavage tool to detect and quantify indel mutations introduced by CRISPR-Cas9 before selection. | Key for early efficiency validation in transient assays. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media (MS, B5) | Provides nutrients and hormones for the regeneration of transformed plant cells after co-cultivation with Agrobacterium. | Composition is highly species- and explant-specific. |

Visualizing Strain Selection and T-DNA Delivery Workflow

Diagram 1: Agrobacterium Strain Selection and T-DNA Delivery Logic Flow

Diagram 2: Vir Gene Induction Pathway and Strain Differences

For an Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 system:

- GV3101 is the unequivocal choice for Arabidopsis thaliana and excels in many dicot leaf disc transient assays due to its robust C58 background.

- EHA105, with its "super-virulent" pTiBo542 plasmid, is frequently necessary to achieve any transformation in recalcitrant dicot crops (soybean, cotton, tree species) and should be prioritized for such challenging systems.

- LBA4404 remains a standard for specific protocols, particularly in rice transformation and some established tomato/tobacco protocols, though it is often surpassed in efficiency by GV3101 or EHA105 in direct comparisons.

A systematic preliminary experiment comparing strains in a transient assay, as outlined, is highly recommended to empirically determine the optimal strain for a novel plant system or genetic construct.

Within the research framework of Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 systems for genome editing, the choice of plant transformation technique is critical for successful gene delivery, editing efficiency, and recovery of modified progeny. This technical guide details three Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated in planta transformation methods, comparing their applications in CRISPR-Cas9 research for generating edited lines without the need for tissue culture.

Core Techniques: Principles and Applications

Floral Dip

This method involves the direct infiltration of developing floral tissues with an Agrobacterium suspension. It is primarily used for Arabidopsis thaliana and some related Brassicaceae species. The bacterium transforms the female gametophyte (ovule) cells, leading to the generation of transformed seeds in the dipped plants.

Leaf Disc

A classical tissue culture-based method where explants (often leaf discs) are co-cultivated with Agrobacterium, followed by selection and regeneration on media containing antibiotics and hormones to produce whole, transgenic plants.

Seedling Infiltration (Vacuum Infiltration)

Young, whole seedlings are submerged in an Agrobacterium suspension and subjected to a vacuum to force the bacterial cells into intercellular spaces, potentially transforming vegetative meristematic cells that can give rise to edited sectors.

Quantitative Comparison of Techniques

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Transformation Techniques for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery

| Parameter | Floral Dip | Leaf Disc | Seedling Infiltration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Species | Arabidopsis thaliana, some Brassicas | Broad (Tomato, Tobacco, Potato, Lettuce) | Arabidopsis, Medicago, Soybean (young) |

| Typical Efficiency (T1) | 0.5% - 5% | 1% - 30% (species-dependent) | 0.1% - 2% |

| Tissue Culture Required | No | Yes | No |

| Time to T1 Seed | ~8-12 weeks | 3-6 months (highly variable) | ~8-12 weeks |

| Chimerism in T1 | Low (transformation of female gametophyte) | Typically low (single-cell origin) | High (vegetative meristem transformation) |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Suitability | Excellent for Arabidopsis knockout/mutant libraries. | Ideal for species with robust regeneration; allows selection of editing events in vitro. | Useful for species recalcitrant to floral dip; requires careful screening for germline edits. |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, no tissue culture, high-throughput. | Applicable to many species, selection possible. | Avoids tissue culture, applicable to some recalcitrant plants. |

| Key Limitation | Mostly limited to Brassicaceae. | Labor-intensive, genotype-dependent regeneration. | High chimerism, lower efficiency, optimization intensive. |

Table 2: Typical Agrobacterium Strain and Vector Components for CRISPR Delivery

| Component | Example | Function in CRISPR Context |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | GV3101 (pMP90), LBA4404, AGL1 | Disarmed vir helper plasmid for T-DNA transfer. |

| Binary Vector Backbone | pCAMBIA, pGreen, pHELLSGATE | Contains T-DNA borders and plant selection marker. |

| Cas9 Expression | CaMV 35S promoter, AtUbi10 promoter | Drives expression of Cas9 nuclease. |

| gRNA Expression | AtU6, OsU3, tRNA-sgRNA polycistron | Polymerase III promoter for guide RNA transcription. |

| Selection Marker | bar (glufosinate), hptII (hygromycin), npII (kanamycin) | Selects for T-DNA integration in tissue culture (Leaf Disc) or in soil (Floral Dip/Seedling). |

| Reporter | GFP, DsRed, GUS | Visual screening of transformation/editing events. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Floral Dip forArabidopsis thaliana(CRISPR-Cas9)

Objective: Generate genome-edited T1 seeds via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the female gametophyte. Key Reagents: Agrobacterium strain GV3101 (pMP90) carrying CRISPR binary vector, 5% sucrose solution, Silwet L-77 surfactant.

- Bacterial Culture: Inoculate Agrobacterium from a single colony in LB with appropriate antibiotics. Grow overnight at 28°C. Pellet and resuspend in 5% sucrose solution to OD₆₀₀ ~0.8.

- Add Surfactant: Add Silwet L-77 to a final concentration of 0.02-0.05% (v/v) to the suspension immediately before dipping.

- Plant Material: Use primary bolts of 4-6 week old plants. Clip off any fully developed siliques to encourage transformation of newly opened flowers.

- Dip: Invert the above-ground plant parts into the bacterial suspension for 15-30 seconds with gentle agitation.

- Post-Dip: Lay plants horizontally in a tray, cover with transparent film to maintain humidity for 18-24 hours. Return to normal growth conditions.

- Seed Harvest: Harvest seeds from dipped bolts when fully dried (approximately 4-6 weeks post-dip). These are the T1 generation.

Protocol 2: Leaf Disc Transformation (for Tomato,Nicotiana benthamiana)

Objective: Regenerate genome-edited plants from co-cultivated leaf explants via tissue culture. Key Reagents: MS media, Acetosyringone, Cytokinin (BAP), Auxin (IAA), appropriate antibiotics for selection (e.g., kanamycin).

- Explants: Surface-sterilize young leaves, cut into 0.5-1 cm² discs.

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow Agrobacterium (e.g., LBA4404) to OD₆₀₀ ~0.5-1.0. Resuspend in MS liquid medium containing 100-200 µM acetosyringone.

- Co-cultivation: Immerse leaf discs in bacterial suspension for 5-10 minutes. Blot dry and place on co-cultivation media (MS + acetosyringone) for 2-3 days in the dark.

- Selection & Regeneration: Transfer discs to regeneration media (MS + BAP + IAA) containing antibiotics (e.g., cefotaxime to kill Agrobacterium and kanamycin to select transformed plant cells). Subculture every 2 weeks.

- Shoot Development: Emerging shoots are transferred to shoot elongation media, then to rooting media containing selection agents.

- Acclimatization: Plantlets with established roots are transferred to soil.

Protocol 3: Seedling Vacuum Infiltration

Objective: Introduce CRISPR-Cas9 T-DNA into vegetative meristems of young seedlings. Key Reagents: Agrobacterium suspension, half-strength MS liquid medium, vacuum apparatus.

- Seedling Growth: Surface-sterilize seeds and germinate on agar plates. Grow seedlings for 3-7 days (until radicle and cotyledons emerge).

- Bacterial Preparation: Prepare as for Floral Dip, resuspending in half-strength MS medium + sucrose + Silwet L-77 (~0.005%).

- Infiltration: Place seedlings in bacterial suspension in a suitable container. Apply vacuum (25-30 in. Hg) for 2-5 minutes. Rapidly release the vacuum.

- Recovery: Blot seedlings and place on sterile filter paper or agar plates for 1-2 days.

- Transfer to Soil: Transplant recovered seedlings to soil and grow to maturity.

- Screening: Harvest T1 seeds from individual branches. Screen for edits, acknowledging high chimerism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Plant Transformation

| Item | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| Binary Vector System (e.g., pCAMBIA-CRISPR) | Carries T-DNA with Cas9, gRNA(s), and plant selection marker for Agrobacterium delivery. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain (e.g., GV3101) | Disarmed strain engineered for efficient plant transformation; helper plasmids provide vir genes in trans. |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces the Agrobacterium vir gene region, enhancing T-DNA transfer efficiency. |

| Silwet L-77 | Non-ionic surfactant that reduces surface tension, enabling Agrobacterium suspension to infiltrate plant tissues. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media (MS Basal Salts) | Provides essential nutrients for explant survival, co-cultivation, and regeneration in the leaf disc method. |

| Selection Agents (e.g., Kanamycin, Glufosinate) | Antibiotics or herbicides used to selectively eliminate non-transformed tissues or plants, identifying potential editing events. |

| PCR & Sequencing Primers for Target Locus | For genotyping putative edited lines to identify insertion/deletion (indel) mutations or precise edits. |

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

Diagram 1: CRISPR Plant Transformation Technique Selection Logic

Diagram 2: Agrobacterium T-DNA Transfer & CRISPR Action Pathway

Within the framework of a thesis on Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 systems for plant genome editing, the efficient recovery of stable transgenic events is a critical, rate-limiting step. The CRISPR-Cas9 machinery, delivered via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT), creates precise genomic edits. However, only a small fraction of treated explants successfully integrate the T-DNA. Selection agents—primarily antibiotics and herbicides—are therefore indispensable for isolating these rare transformation events. This guide details the technical application of these markers for the selection and regeneration of edited plants, focusing on current methodologies and quantitative benchmarks.

The Role of Selection Markers in CRISPR-Cas9 Workflows

In an editing pipeline, the T-DNA typically carries both the CRISPR-Cas9 components (Cas9, gRNA) and a selectable marker gene. The marker confers resistance to a toxic compound present in the culture media. Non-transformed cells die or are severely inhibited, while transformed cells proliferate and regenerate into whole plants. For research, the marker is often excised in subsequent generations using genetic strategies (e.g., Cre-lox) to produce marker-free edited plants.

Quantitative Comparison of Common Selection Agents

The efficacy of a selection agent depends on the plant species, explant type, and transformation protocol. The table below summarizes key performance data for widely used agents.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Common Antibiotic and Herbicide Selection Agents

| Selection Agent | Typical Working Concentration (mg/L) | Mode of Action | Common Resistance Gene | Average Selection Efficiency (% PCR+ Events) | Average Escape Rate (%) | Phytotoxicity Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanamycin | 50-100 (dicots) 100-200 (monocots) | Inhibits protein synthesis (30S ribosomal subunit) | nptII (neomycin phosphotransferase II) | 60-80% | 10-25% | Moderate-High (can bleach shoots) |

| Hygromycin B | 10-50 | Inhibits protein synthesis (ribosome translocation) | hpt (hygromycin phosphotransferase) | 70-90% | 5-15% | High (rapid browning/death) |

| Glufosinate (Basta) | 1-5 (in vitro) 0.1-0.3% (spray) | Inhibits glutamine synthetase (ammonia accumulation) | bar or pat (phosphinothricin acetyltransferase) | 75-95% | 1-10% | Low-Moderate (species-dependent) |

| Glyphosate | 1-10 (in vitro) | Inhibits EPSPS enzyme in shikimate pathway | cp4 epsps (aroA) | 65-85% | 5-20% | Variable (can cause callus necrosis) |

Data compiled from recent literature (2022-2024). Efficiency and escape rates are species- and protocol-dependent ranges.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of Minimum Lethal Concentration (MLC) for Explants

Objective: To establish the optimal selection pressure that kills 100% of non-transformed explants with minimal impact on transgenic cell viability. Materials: Sterile explants (e.g., leaf discs, hypocotyls), basal culture media, stock solutions of selection agent. Procedure:

- Prepare media plates with a logarithmic series of the selection agent (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 mg/L for hygromycin).

- Plate 20-30 explants per concentration, ensuring even contact with the media.

- Incubate under standard growth conditions (e.g., 25°C, 16/8h light/dark).

- Monitor weekly for 4 weeks. Score explants for signs of necrosis, bleaching, or complete death.

- The MLC is the lowest concentration that causes 100% death or complete inhibition of growth/regeneration of all control explants by week 4.

- The optimal selection concentration is typically 1.2x to 1.5x the MLC.

Protocol:Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation with Dual Selection (Cas9 + Marker)

Objective: To deliver CRISPR-Cas9 T-DNA and select putative transgenic events. Materials: Agrobacterium strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101) harboring binary vector with Cas9, gRNA, and hpt gene; explants; co-cultivation media; selection media containing antibiotic (for plant selection) and cefotaxime/timentin (for Agrobacterium elimination). Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Incubate explants on pre-culture media for 24-48h.

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow Agrobacterium to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.5-0.8). Pellet and resuspend in liquid co-cultivation media to OD600 0.05-0.2.

- Inoculation: Immerse explants in bacterial suspension for 10-30 minutes. Blot dry on sterile filter paper.

- Co-cultivation: Transfer explants to solid co-cultivation media. Incubate in dark at 22-25°C for 2-3 days.

- Selection & Regeneration: Transfer explants to selection/regeneration media containing the determined concentration of the selection agent (e.g., hygromycin B) and 250-500 mg/L cefotaxime.

- Subculture: Transfer surviving explants or emerging shoots to fresh selection media every 2-3 weeks.

- Elongation & Rooting: Once shoots develop, transfer to selection media for elongation, then to rooting media (often with a lower selection agent concentration).

- Molecular Confirmation: Perform PCR on genomic DNA from putative events to confirm presence of transgene (Cas9, marker) and desired edit via sequencing.

Visualizing the Selection Workflow and Molecular Pathways

Diagram Title: Workflow for Transgenic Event Selection & Regeneration

Diagram Title: Molecular Mechanism of Antibiotic vs. Herbicide Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Selection and Regeneration Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector System (e.g., pCAMBIA, pGreen) | Carries T-DNA with CRISPR-Cas9 cassette and selectable marker gene. | Ensure compatible with Agrobacterium strain. Use modular systems for easy gRNA cloning. |

| Agrobacterium Strain (e.g., LBA4404, EHA105, GV3101) | Mediates T-DNA transfer into plant genome. | Strains vary in virulence. EHA105 is often more efficient for monocots. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media (MS, B5, N6 basal salts) | Provides nutrients and hormones for explant survival and regeneration. | Optimize sucrose concentration and pH (5.7-5.8). Add hormones (auxins/cytokinins) for callus/shoot induction. |

| Selection Agent Stock Solutions | High-purity, filter-sterilized stocks (e.g., 50 mg/mL hygromycin in H2O). | Store at -20°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw. Verify bioactivity for critical experiments. |

| β-lactam Antibiotics (Cefotaxime, Timentin) | Eliminate Agrobacterium after co-cultivation without harming plant tissue. | Timentin is often more effective against persistent strains and less phytotoxic. |

| Plant Growth Regulators (e.g., 2,4-D, BAP, NAA) | Direct cell fate (callus, shoot, root formation). | Concentration is critical; slight changes can alter regeneration outcome. |

| gDNA Isolation Kit (Plant-specific) | Extract PCR-quality DNA from regenerated shoots for genotyping. | Must handle polysaccharide- and polyphenol-rich tissues. |

| PCR Reagents & Sanger Sequencing | Confirm transgene integration and analyze CRISPR-induced edits. | Use high-fidelity polymerases for cloning. Design primers flanking target site. |

The deployment of an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 system is a cornerstone of modern plant genome editing research. Following transformation and regeneration, the initial regenerated plants are termed primary transformants (T0). These individuals represent a genetically heterogeneous population due to variable transgene integration, copy number, and editing efficiency. Rigorous screening of T0 plants is therefore critical to identify those with desired, heritable edits before progressing to the next generation (T1). This guide details three essential and complementary techniques for initial T0 screening: PCR for transgene detection, Sanger sequencing for initial edit confirmation, and the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay for assessing editing efficiency and identifying heterozygotes.

Detailed Methodologies

Genomic DNA (gDNA) Isolation (Prerequisite)

- Protocol: Use a reliable plant DNA extraction kit or a modified CTAB method. For quick screening, a rapid alkaline lysis method can be used: excise a small leaf disc (~3 mm), grind in 50 µL of 0.25 M NaOH, heat at 95°C for 30 sec, add 50 µL of 0.25 M HCl and 100 µL of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), vortex, and use 1-2 µL of supernatant as PCR template.

- Quality Check: Assess gDNA purity and concentration via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ~1.8).

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for Transgene Detection

- Purpose: Confirm the presence of the T-DNA, specifically the Cas9 and/or selectable marker genes.

- Protocol:

- Primer Design: Design gene-specific primers (18-22 bp, Tm ~60°C) for a 150-300 bp fragment of the Cas9 gene and the plant selectable marker (e.g., NPTII, HPT).

- Reaction Setup (20 µL):

- 10-50 ng gDNA template

- 0.2 µM each forward and reverse primer

- 1X PCR master mix (containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂)

- Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 min.

- 35 Cycles: 95°C for 30 sec, 58-60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec/kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min.

- Analysis: Run PCR products on a 1-1.5% agarose gel. A clear band of expected size indicates transgene presence.

Sanger Sequencing of the Target Locus

- Purpose: Directly read the nucleotide sequence around the target site to confirm the presence and nature of indels (insertions/deletions).

- Protocol:

- Amplification: Perform a high-fidelity PCR (using primers 200-300 bp flanking the target site) to generate a clean amplicon for sequencing.

- Purification: Purify the PCR product using a spin column or enzymatic cleanup.

- Sequencing Reaction: Submit purified amplicon for Sanger sequencing with one of the PCR primers.

- Analysis: Visualize chromatograms using software (e.g., SnapGene, 4Peaks). A clean, single sequence indicates a homozygous or biallelic edit. Overlapping peaks downstream of the cut site indicate a heterozygous or mosaic edit.

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay

- Purpose: Detect mismatches in heteroduplex DNA formed by annealing wild-type and mutant alleles, providing a semi-quantitative measure of editing efficiency.

- Protocol:

- Amplification: Perform a high-fidelity PCR on the target region (as in 2.3).

- Heteroduplex Formation: Purify the PCR product. Use a thermocycler: 95°C for 5 min, ramp down to 85°C at -2°C/sec, then to 25°C at -0.1°C/sec. Hold at 4°C.

- Digestion: Assemble a 20 µL reaction: 200 ng re-annealed PCR product, 1X NEBuffer 2.1, 0.5 µL T7 Endonuclease I (NEB #M0302). Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 min.

- Analysis: Run digested products on a 2-2.5% agarose gel. Cleavage into two or more fragments indicates the presence of edits. Calculate approximate editing efficiency using band intensity densitometry: % Indel = [1 - √(1 - (b+c)/(a+b+c))] × 100, where a is the integrated intensity of the undigested band, and b & c are the digested bands.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of T0 Screening Methods

| Method | Primary Purpose | Detection Limit | Time Required | Key Outcome | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Transgene presence | Single copy | ~3 hours | Binary (Yes/No) | Initial transformant confirmation |

| Sanger Sequencing | Sequence confirmation | ~15-20% allele fraction | 1-2 days | Exact nucleotide change | Identifying homozygous/biallelic edits |

| T7E1 Assay | Edit efficiency & heterozygosity | ~1-5% indel frequency | 1 day | Semi-quantitative % indels | Rapid screening of heterozygous/mosaic edits |

Visualization of the T0 Screening Workflow

T0 Plant Screening Decision & Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for T0 Screening

| Item | Function & Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Plant DNA Extraction Kit | Standardized silica-column or magnetic-bead based system for high-quality, PCR-ready gDNA. |

| Rapid Alkaline Lysis Buffer | Quick, inexpensive solution for direct PCR from leaf tissue, ideal for high-throughput screening. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme with proofreading activity to minimize PCR errors crucial for sequencing and T7E1 assays. |

| Standard Taq Polymerase Mix | Reliable, cost-effective enzyme for routine transgene detection PCR. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Surveyor nuclease family enzyme that cleaves mismatches in heteroduplex DNA at CRISPR target sites. |

| Agarose & Gel Electrophoresis System | For size-based separation and visualization of PCR and digested DNA fragments. |

| DNA Gel Stain (Safe/EtBr) | Intercalating dye for visualizing DNA bands under UV/blue light. |

| PCR Product Purification Kit | Removes primers, dNTPs, and enzymes to prepare clean DNA for sequencing or T7E1 assay. |

| Sanger Sequencing Service | External or in-house capillary electrophoresis service for definitive sequence determination. |

| Chromatogram Analysis Software | Tool for visualizing and interpreting sequencing traces to identify indels. |

Maximizing Editing Efficiency: Troubleshooting Common Pitfalls in Agrobacterium CRISPR Delivery

Within the research framework of an Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 system for plant genome editing, transformation efficiency is a critical bottleneck. This guide details optimization strategies for three core parameters: Agrobacterium culture optical density (OD), acetosyringone concentration, and co-culture conditions, to maximize T-DNA delivery and stable integration.