Cas Protein Variants Efficiency Comparison: A Strategic Guide for Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the editing efficiency and specificity of diverse CRISPR-Cas protein variants, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Cas Protein Variants Efficiency Comparison: A Strategic Guide for Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the editing efficiency and specificity of diverse CRISPR-Cas protein variants, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational landscape of Class 2 Cas nucleases and engineered derivatives, explores methodological applications in therapeutic contexts, details troubleshooting strategies for common challenges like off-target effects, and presents a validated, comparative framework for nuclease selection. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide aims to empower strategic decision-making in preclinical research and clinical translation, enabling the choice of the optimal Cas variant for specific experimental and therapeutic goals.

The Expanding CRISPR-Cas Landscape: From Natural Diversity to Engineered Precision

Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems represent a revolutionary group of gene-editing tools derived from bacterial adaptive immune mechanisms. These systems are defined by their utilization of a single, multi-domain Cas protein effector complex, in contrast to Class 1 systems that require multiple protein subunits for functionality [1] [2]. This fundamental architectural simplification has propelled Class 2 systems, particularly Cas9, to the forefront of genome engineering due to their relative ease of programming and delivery [3]. While Class 1 systems constitute approximately 90% of all CRISPR loci found in bacteria and archaea, Class 2 systems have become the workhorses of modern biotechnology and therapeutic development [1].

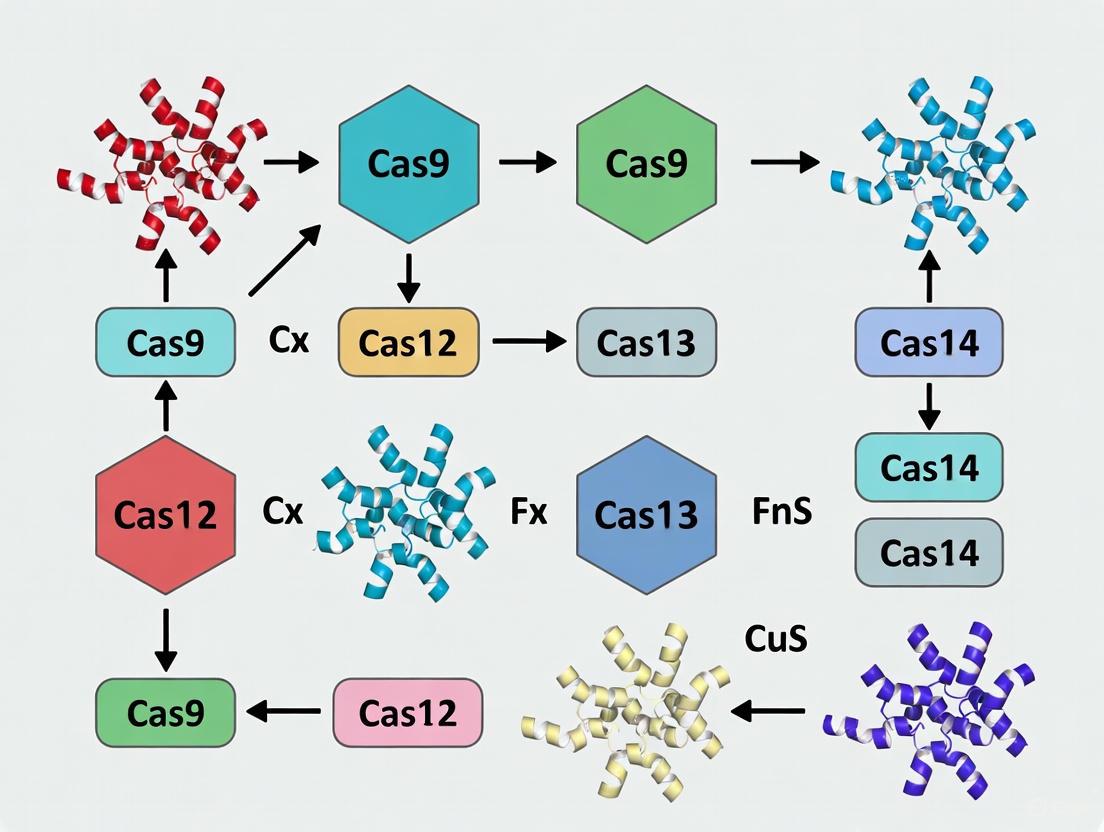

The classification of CRISPR-Cas systems has evolved significantly, with current taxonomy recognizing two classes (Class 1 and Class 2), seven types, and 46 subtypes based on evolutionary relationships and effector module composition [4]. Class 2 systems encompass three main types: Type II (featuring Cas9), Type V (featuring Cas12 proteins), and Type VI (featuring Cas13 proteins) [3] [5]. This review will focus specifically on the DNA-targeting effectors within Class 2, primarily Cas9 and Cas12 proteins, which have been extensively characterized and engineered for diverse genome editing applications. These systems have demonstrated remarkable versatility across basic research, agricultural biotechnology, diagnostic development, and therapeutic interventions, outperforming previous gene-editing platforms like ZFNs and TALENs in ease of design, cost-effectiveness, and multiplexing capability [6] [7].

Molecular Architecture and Mechanisms of DNA-Targeting Effectors

Type II Effector: Cas9 Structure and Function

The Cas9 protein from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) serves as the prototypical Type II effector and remains the most extensively characterized and utilized CRISPR enzyme. SpCas9 exhibits a bilobed architecture consisting of a recognition lobe (REC) and a nuclease lobe (NUC) [2]. The REC lobe, composed primarily of REC1, REC2, and REC3 domains, is responsible for guide RNA binding and recognition of the target DNA-RNA heteroduplex. The NUC lobe contains the HNH and RuvC nuclease domains, along with the PAM-interacting (PI) domain that facilitates protospacer adjacent motif recognition [2].

Cas9 functions as a complex with a two-component guide system comprising CRISPR RNA (crRNA) containing the target-complementary spacer and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which can be fused into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for simplified applications [2] [8]. The mechanism of Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage involves multiple conformational checkpoints that ensure target fidelity. Initially, the Cas9-sgRNA complex scans genomic DNA for complementary sequences adjacent to a PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) [8]. PAM recognition triggers local DNA melting and enables seed sequence (PAM-proximal 10-12 nucleotides) hybridization between the sgRNA and target DNA [2]. Successful seed pairing initiates complete R-loop formation through zipper-like progression of RNA-DNA base pairing, culminating in large-scale conformational rearrangements that position the HNH domain to cleave the target strand and the RuvC domain to cleave the non-target strand [2]. This concerted nuclease activity generates a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [5].

Type V Effectors: Cas12 Family Diversity

The Cas12 protein family (formerly known as Cpf1) represents Type V effectors with distinct structural and mechanistic features that differentiate them from Cas9 orthologs. Cas12 proteins are generally smaller than Cas9 enzymes, recognize T-rich PAM sequences, and contain a single RuvC nuclease domain that cleaves both DNA strands [5]. Unlike Cas9, Cas12 processes its own crRNA precursors without requiring tracrRNA, simplifying guide RNA design and delivery [3]. Furthermore, Cas12 generates staggered DNA breaks with 5' overhangs rather than blunt ends, potentially enhancing homology-directed repair efficiency [5].

Cas12 effectors exhibit substantial diversity, with Cas12a (Cpf1) being the most well-characterized family member. The mechanism of Cas12a-mediated DNA cleavage involves PAM recognition (5'-TTTN for AsCas12a), followed by DNA unwinding and R-loop formation. Upon target recognition, the RuvC domain becomes allosterically activated, first cleaving the non-target strand and subsequently cleaving the target strand [5]. Notably, Cas12 enzymes exhibit trans-cleavage activity (collateral cleavage) against single-stranded DNA following target recognition, a property that has been harnessed for diagnostic applications such as DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter (DETECTR) [3].

Comparative Analysis of DNA-Targeting Class 2 Effectors

Key Characteristics and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Features of Major DNA-Targeting Class 2 Effectors

| Effector | Class/Type | PAM Requirement | Cleavage Pattern | Size (aa) | Guide RNA Components | Target | Collateral Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | II/Type II | 5'-NGG-3' | Blunt ends | 1368 | crRNA + tracrRNA | dsDNA | No |

| SaCas9 | II/Type II | 5'-NNGRRT-3' | Blunt ends | 1053 | crRNA + tracrRNA | dsDNA | No |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | V/Type V | 5'-TTTN-3' | Staggered (5' overhang) | 1300-1500 | crRNA only | dsDNA/ssDNA | ssDNA |

| hfCas12Max | V/Type V | 5'-TN-3' | Staggered (5' overhang) | 1080 | crRNA only | dsDNA | Minimal |

| eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) | II/Type II | 5'-NGG-3' | Blunt ends | ~1360 | crRNA + tracrRNA | dsDNA | No |

Editing Efficiency and Specificity Data

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Class 2 DNA-Targeting Effectors

| Effector | On-target Efficiency Range | Relative Off-target Rate | Key Applications | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | 60-81% | High (unmodified) | Gene knockout, activation, repression | Most widely characterized; high activity but notable off-targets |

| SaCas9 | 45-75% | Moderate | In vivo therapeutic applications | Compact size enables AAV delivery; good tissue penetration |

| Cas12a | 40-70% | Low to moderate | Multiplex editing, diagnostics | Self-processing crRNA arrays; staggered cuts enhance HDR |

| hfCas12Max | 70-85% | Very low | Therapeutic development | Engineered high-fidelity variant; broad PAM recognition |

| eSpOT-ON | 65-80% | Very low | Clinical-grade editing | Retains high on-target with minimal off-target effects |

Experimental Protocols for Effector Characterization

On-target Editing Efficiency Assessment

Protocol 1: Measuring Gene Disruption Efficiency in Mammalian Cells

Cell Preparation: Seed HEK293T or other relevant cell lines in 24-well plates at 60-70% confluence 24 hours before transfection.

Editor Delivery: Transfect cells with 500 ng of Cas expression plasmid (e.g., SpCas9, SaCas9, or Cas12 variant) and 250 ng of guide RNA expression plasmid using lipofectamine 3000 or polyethyleneimine (PEI). Include a GFP expression plasmid as transfection control.

Harvesting and DNA Extraction: 72 hours post-transfection, harvest cells and extract genomic DNA using silica-column based kits.

Target Amplification: Design PCR primers flanking the target site (amplicon size: 400-800 bp). Perform PCR amplification using high-fidelity DNA polymerase.

Next-generation Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries using dual-indexing strategies. Sequence on Illumina platforms to obtain minimum 50,000 reads per sample.

Analysis Pipeline: Process raw reads through alignment to reference sequence. Quantify insertion-deletion (indel) frequencies at target site using computational tools like CRISPResso2.

Validation: Include positive controls (validated gRNAs) and negative controls (non-targeting gRNAs) in each experiment. Perform technical triplicates for statistical robustness [5] [8].

Genome-wide Off-target Profiling

Protocol 2: CIRCLE-seq for Comprehensive Off-target Detection

Genomic DNA Isolation: Extract high molecular weight genomic DNA from target cells using gentle extraction methods to minimize shearing.

DNA Circularization: Fragment DNA to 1-5 kb fragments using controlled enzymatic fragmentation. Perform intramolecular ligation using T4 DNA ligase in dilute conditions to favor circularization.

In Vitro Cleavage: Incubate circularized DNA with preassembled Cas-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes (50 nM RNP) in appropriate reaction buffer for 4 hours at 37°C.

Linear Molecule Enrichment: Treat reactions with ATP-dependent exonuclease to degrade remaining linear DNA fragments, enriching for Cas-cleaved linearized molecules.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Add sequencing adapters to linearized fragments using tagmentation or blunt-end ligation approaches. Amplify libraries with 8-12 PCR cycles and sequence on Illumina platforms.

Bioinformatic Analysis: Map sequencing reads to reference genome, identifying sites with exact alignment junctions. Compare cleavage sites with in silico predictions and validate top candidates by amplicon sequencing [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Class 2 Effector Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas Experimentation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Plasmids | pX330 (SpCas9), pX601 (Cas12a) | Mammalian expression of Cas effectors and guide RNAs |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAVs (serotypes 2, 6, 8, 9), Lentivirus, Lipid Nanoparticles | In vitro and in vivo delivery of CRISPR components |

| Validation Tools | T7 Endonuclease I, TIDE analysis, NGS validation kits | Detection and quantification of editing events |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T, HCT116, iPSCs, Primary T-cells | Model systems for editing efficiency and specificity testing |

| Off-target Detection | GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq, Digenome-seq kits | Genome-wide identification of unintended editing events |

Class 2 CRISPR-Cas DNA-targeting effectors have established themselves as powerful tools for precision genome engineering, with each effector variant offering distinct advantages for specific applications. While SpCas9 remains the most widely utilized platform due to its high activity and extensive characterization, emerging engineered variants like hfCas12Max and eSpOT-ON address critical limitations regarding off-target effects and PAM restrictions. The continued diversification and optimization of these systems through both discovery of natural variants and protein engineering approaches will further expand their utility in basic research and therapeutic development. As the field advances, the comprehensive understanding of effector mechanisms, editing efficiencies, and specificity profiles will enable researchers to make informed selections of the most appropriate platforms for their specific experimental and clinical objectives.

The CRISPR-Cas system has revolutionized genetic engineering, offering unprecedented control over genome manipulation. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate Cas protein is paramount to experimental and therapeutic success. The efficiency of these molecular tools is primarily defined by three interconnected characteristics: their Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) requirements, which dictate targetable genomic sites; their physical size, which impacts deliverability; and their cleavage mechanics, which influence repair outcomes and precision. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of the most widely used Cas protein variants, equipping scientists with the data necessary to make informed decisions for their specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of Major Cas Variants

The following tables synthesize the key characteristics and performance metrics of prominent Cas nucleases, providing a direct comparison of their targeting scope, structural properties, and editing outcomes.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Cas Nucleases

| Cas Nuclease | Size (aa) | PAM Sequence (5'→3') | Cleavage Type | Cut End Geometry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (Streptococcus pyogenes) | 1368 [9] | NGG (canonical); also recognizes NAG, NGA [8] | Blunt-ended DSB [8] | Blunt end |

| SaCas9 (Staphylococcus aureus) | 1053 [8] | NNGRRT (prefers NNGGGT) [10] [8] | Blunt-ended DSB [8] | Blunt end |

| Cas12a (e.g., LbCas12a) | ~1300 | TTTV (V = A, C, G) [11] | Staggered DSB [11] | 5' overhang |

| AsCas12a | - | TTTV [10] | Staggered DSB [10] | 5' overhang |

| Flex-Cas12a (Engineered) | - | NYHV (expanded from TTTV) [11] | Staggered DSB [11] | 5' overhang |

| hfCas12Max (Engineered) | 1080 [8] | TN (greatly expanded) [8] | Staggered DSB [8] | 5' overhang |

| Nme1Cas9 (Neisseria meningitidis) | - | NNNNGATT [10] | Blunt-ended DSB | Blunt end |

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Applications in Genome Editing

| Cas Nuclease | Targetable Human Genome | Key Editing Performance Findings | Primary Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | >6% [11] | Higher total editing levels vs. Cas12a in some studies; more unintended large-scale repair events [12] [13] | Broad research use; delivery challenging due to large size [8] |

| SaCas9 | - | Efficient indel generation in plants; used in neuronal and liver disease models [8] | Ideal for AAV delivery due to small size [8] |

| Cas12a (LbCas12a) | ~1% (canonical) [11] | Similar total editing to Cas9 with ssODN; higher precision in templated editing [12] | Preferred for precise HDR; multiplexing via crRNA arrays [12] [11] |

| Flex-Cas12a (Engineered) | ~25% [11] | Retains efficient cleavage at canonical sites while recognizing non-canonical PAMs [11] | Expands accessible loci for therapy and agriculture [11] |

| hfCas12Max (Engineered) | Vastly expanded (TN PAM) [8] | Enhanced on-target editing with reduced off-targets [8] | Therapeutic development (e.g., Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy) [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Cas Protein Efficiency

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of CRISPR-Cas experiments, standardized protocols for evaluating nuclease efficiency are critical. Below are detailed methodologies for key characterization assays.

Protocol 1: Determining PAM Recognition Profiles in Mammalian Cells

The PAM-readID (PAM REcognition-profile-determining Achieved by DsODN Integration) method is a rapid and accurate approach for defining the functional PAM specificity of Cas nucleases in a mammalian cellular environment [10].

Workflow Diagram: PAM-readID Method

Detailed Procedure:

- Library Construction: A plasmid library is constructed where a fixed target protospacer sequence is flanked by a fully randomized PAM region (e.g., 6N for Cas9) [10].

- Cell Transfection: Mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T) are co-transfected with three components:

- The PAM library plasmid.

- A second plasmid expressing the Cas nuclease and its corresponding guide RNA.

- A defined double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag.

- Cleavage and Tag Integration: After 72 hours, genomic DNA is extracted. During this period, the Cas nuclease cleaves library plasmids bearing recognized PAMs. The cellular Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) repair machinery then integrates the dsODN tag into the cleavage site [10].

- Amplification and Sequencing: The cleaved and tagged fragments are selectively amplified via PCR using one primer binding to the integrated dsODN tag and another primer binding to the target plasmid. This ensures that only sequences which were cleaved and repaired are amplified [10].

- Data Analysis: The resulting amplicons are subjected to high-throughput sequencing. The sequenced reads are analyzed to identify the PAM sequences present immediately adjacent to the integrated dsODN tag, revealing the PAM recognition profile of the nuclease. The method is sensitive enough to produce an accurate profile for SpCas9 with as few as 500 sequencing reads [10].

Protocol 2: Comparing Gene Editing Efficiency and Precision

This protocol outlines a direct comparison of editing outcomes between Cas9 and Cas12a when using single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair templates, a common scenario for introducing specific point mutations [12].

Workflow Diagram: Cas9 vs. Cas12a Editing Comparison

Detailed Procedure:

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: For both Cas9 and Cas12a, form RNP complexes in vitro by pre-complexing the purified Cas nuclease with their respective synthetic guide RNAs targeting overlapping regions of the same genomic locus (e.g., within a gene like FKB12) [12].

- Co-delivery into Cells: Co-deliver the RNP complexes along with an ssODN repair template containing the desired homologous sequence into the target cells (e.g., the alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) via methods such as electroporation or lipid nanoparticle (LNP) transfection [12].

- Cell Culture and Viability Assessment: Culture the transfected cells and assess viability. The number of viably recovered cells is a critical metric for evaluating the comparative cytotoxicity of the nucleases [12].

- Outcome Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from the recovered cell pools and perform PCR amplification of the targeted locus.

- Total Editing Efficiency: Use high-throughput amplicon sequencing (e.g., Illumina) to quantify the percentage of sequencing reads containing insertions or deletions (indels) at the target site for each nuclease [12].

- Precision Editing Efficiency: Analyze the same sequencing data to quantify the percentage of reads that contain the exact sequence change specified by the ssODN template, indicating successful Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). A study using this methodology found that while Cas9 and Cas12a achieved similar total editing levels (20-30%), Cas12a demonstrated a slightly higher level of precision editing [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of CRISPR experiments requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for characterizing Cas protein efficiency.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PAM Library Plasmid | A plasmid vector containing a randomized DNA sequence (e.g., 6N) adjacent to a fixed protospacer, representing all possible PAM combinations. | Serves as the substrate for in vivo PAM determination assays like PAM-readID to define a nuclease's functional PAM recognition profile [10]. |

| dsODN Tag | A short, defined double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide. | Serves as a marker for Cas-induced double-strand breaks in methods like PAM-readID and GUIDE-seq; integrated into cleavage sites via NHEJ to tag and later amplify the cleaved sequence [10]. |

| Synthetic Guide RNA (gRNA) | Chemically synthesized crRNA (for Cas12a) or sgRNA (for Cas9). Offers high purity and consistency compared to in vitro transcribed guides. | Used in RNP complex formation for consistent editing; studies show measuring only indels may underestimate activity, and different gRNAs can have varying outcomes in terms of large-scale repair events [13]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex | A pre-assembled complex of the Cas protein and its guide RNA. | The preferred delivery method for many experiments; minimizes off-target effects and reduces cytotoxicity by limiting the window of nuclease activity inside the cell. |

| ssODN Repair Template | A single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing homology arms flanking the desired edit. | Serves as the donor template for precise genome editing via the HDR pathway; co-delivered with CRISPR components to introduce specific point mutations or small inserts [12]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery vehicle composed of lipid droplets that can encapsulate CRISPR components like mRNA or RNPs. | Enables efficient in vivo delivery of CRISPR machinery; has a natural tropism for the liver and allows for potential re-dosing, as demonstrated in clinical trials [14]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | A viral vector commonly used for in vivo gene delivery. | Used to deliver CRISPR genes in vivo; its limited cargo capacity makes smaller nucleases like SaCas9 (∼1kb smaller than SpCas9) particularly advantageous [8]. |

The choice of Cas nuclease is a fundamental determinant of experimental success in genome engineering. As the data demonstrates, there is no single "best" nuclease; rather, the optimal choice is dictated by the specific research goal. SpCas9 remains a versatile workhorse with a broad PAM, while its smaller ortholog SaCas9 is indispensable for AAV-based therapeutic delivery. Cas12a variants offer distinct advantages for precision editing and multiplexing, with their staggered cuts and simpler guide RNAs. The emergence of engineered high-fidelity variants like hfCas12Max and PAM-relaxed enzymes like Flex-Cas12a is pushing the boundaries of targetable space and specificity. By aligning the key characteristics of PAM requirement, size, and cleavage mechanics with their experimental or therapeutic objectives, researchers can strategically leverage the growing CRISPR toolkit to advance both basic science and clinical applications.

The CRISPR-Cas system has revolutionized genetic engineering, but its application has been constrained by two fundamental limitations: the requirement for a specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site, and the potential for off-target effects. The PAM sequence, typically 2-6 base pairs in length, is essential for Cas nuclease recognition and cleavage but significantly restricts the targeting scope of CRISPR systems [15]. Simultaneously, imperfect complementarity between guide RNA (gRNA) and target DNA can lead to unintended cleavage at off-target sites, compromising experimental accuracy and therapeutic safety [16]. In response to these challenges, extensive protein engineering efforts have yielded novel Cas variants with expanded PAM recognition and enhanced fidelity. This comparison guide objectively analyzes the performance of these engineered variants, providing researchers with experimental data to inform their selection of appropriate tools for specific genome editing applications.

Experimental Approaches for Characterizing Cas Variants

Method 1: GenomePAM for PAM Characterization

The GenomePAM method enables direct PAM characterization in mammalian cells by leveraging highly repetitive genomic sequences as natural target site libraries. This approach eliminates the need for protein purification or synthetic oligo libraries [17].

Protocol:

- Identify a 20-nt repetitive sequence (e.g., Rep-1: 5′-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3′) that occurs thousands of times in the human genome with nearly random flanking sequences.

- Clone the corresponding spacer into a gRNA expression cassette.

- Co-transfect with a plasmid encoding the candidate Cas nuclease into mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T).

- Capture cleavage sites using GUIDE-seq methodology, which enriches dsODN-integrated fragments via anchor multiplex PCR sequencing.

- Sequence and analyze cleaved genomic regions to identify functional PAM requirements [17].

Method 2: PEM-seq for Comprehensive Editing Analysis

Primer-Extension-Mediated Sequencing (PEM-seq) provides a high-throughput method for simultaneously assessing on-target efficiency, off-target activity, and DNA repair outcomes.

Protocol:

- Transfert cells with Cas plasmid and sgRNA plasmid.

- Sort successfully transduced cells using FACS (based on mCherry and GFP markers) 72 hours post-transfection.

- Extract genomic DNA and perform primer extension with a biotinylated primer designed near the Cas9 target site.

- Amplify extended products using site-specific nested primers.

- Prepare Illumina sequencing libraries and sequence.

- Analyze outcomes including indels, large deletions, and off-target translocations [18].

Method 3: Structure-Guided Protein Engineering for Enhanced Fidelity

Rational design of high-fidelity variants through structural analysis involves identifying amino acid residues that interact with the DNA backbone and introducing mutations to reduce non-specific binding.

Protocol:

- Analyze high-resolution Cas protein structures to identify residues forming hydrogen bonds with the target DNA backbone within 3.0-Å distance.

- Generate alanine substitution mutants to weaken non-specific DNA contacts.

- Test variants using a human cell-based disruption assay (e.g., EGFP disruption) with both perfectly matched and mismatched crRNAs.

- Evaluate on-target efficiency at multiple endogenous sites using T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay.

- Assess mismatch tolerance by testing against crRNAs with single and double mismatches across the protospacer region [16].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Engineered Cas Variants

PAM Flexibility and Editing Efficiency

Table 1: PAM Compatibility and Editing Efficiency of PAM-Flexible SpCas9 Variants

| Variant | PAM Requirement | Relative On-target Efficiency (%) | Off-target Ratio | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type SpCas9 | NGG | 100 (reference) | High | Original nuclease with strong activity but restricted targeting [18] |

| xCas9(3.7) | NG, GAA, GAT | 56-98% at NGG sites | Moderate | Broad PAM recognition with varying efficiency across sites [18] |

| Cas9-NG | NG | 47-85% at NGG sites | Moderate | Extended targeting to NG PAMs [18] |

| SpG | NGN | 60-95% at NGG sites | Moderate | Expanded recognition to all NGN PAMs [18] |

| SpRY | NRN > NYN | 25-79% at NGG sites | High | Near-PAMless variant, highest flexibility but increased off-target risk [18] |

Fidelity and Off-Target Profiles

Table 2: Performance Comparison of High-Fidelity Cas Variants

| Variant | Parental Nuclease | Relative On-target Efficiency (%) | Off-target Reduction | Key Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSpCas9(1.1) | SpCas9 | 85-110 | 10-100× | K848A, K1003A, R1060A [19] [18] |

| SpCas9-HF1 | SpCas9 | 80-105 | 10-100× | N497A, R661A, Q695A, Q926A [19] [18] |

| HypaCas9 | SpCas9 | 75-110 | 5-50× | N692A, M694A, Q695A, H698A [18] |

| evoCas9 | SpCas9 | 10-95 (highly variable) | 10-100× | M495V, Y515N, K526E, R661Q [18] |

| Sniper-Cas9 | SpCas9 | 70-100 | 5-50× | F539S, M763I, K890N [18] |

| HyperFi-As | AsCas12a | 90-115 | Dramatically reduced | S186A/R301A/T315A/Q1014A/K414A [16] |

| AsCas12a4m | AsCas12a | 90-100 | Significantly reduced | S186A/R301A/T315A/Q1014A [16] |

Engineering Strategies and Molecular Mechanisms

Engineering PAM Flexibility

The following diagram illustrates the strategic approach to developing Cas variants with expanded PAM recognition:

Enhancing Fidelity Through Engineering

The molecular approaches to improving Cas nuclease specificity focus on reducing non-specific interactions with DNA:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas Variant Characterization

| Reagent / Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GenomePAM | Direct PAM characterization using genomic repeats | Identifies PAM requirements in mammalian cellular context [17] |

| PEM-seq | Comprehensive editing analysis | Detects on/off-target editing, translocations, and large deletions [18] |

| GUIDE-seq | Genome-wide off-target profiling | Identifies double-strand breaks enabled by sequencing [17] [16] |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay | Mutation detection measurement | Quantifies indel frequencies at target sites [16] [18] |

| EGFP Disruption Assay | Functional activity assessment | Measures nuclease activity via fluorescence loss [16] |

| Single-Molecule Unzipping Assay | R-loop complex stability evaluation | Characterizes Cas-RNA-DNA complex dynamics [16] |

The engineering of CRISPR-Cas variants has produced remarkable advances in both PAM flexibility and editing fidelity, yet the experimental data reveal an inherent trade-off between these two properties. PAM-flexible variants like SpRY achieve near-PAMless editing but exhibit significantly increased off-target activity, while high-fidelity variants maintain specificity but may show reduced activity at certain loci [18]. The development of combined variants that integrate both PAM expansion and fidelity-enhancing mutations represents a promising direction for future research. For therapeutic applications where specificity is paramount, high-fidelity variants like eSpCas9(1.1), HypaCas9, or HyperFi-AsCas12a offer superior performance despite their more restricted targeting range [16] [18]. For screening applications or targeting specific genomic regions with limited PAM options, PAM-flexible variants like SpG or SpRY provide necessary coverage at the cost of increased off-target risk. Researchers must carefully consider these performance characteristics when selecting Cas variants for specific experimental or therapeutic applications.

The discovery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, providing researchers with an unprecedented ability to modify DNA with precision and relative ease. However, Cas9 is merely one member of a diverse and growing arsenal of gene-editing technologies. As research advances, systems like Cas12, Cas13, and prime editing have emerged with distinct capabilities that address fundamental limitations of the original CRISPR-Cas9 platform. While Cas9 remains the gold standard for DNA disruption, these alternative technologies offer specialized functions—from targeting RNA to achieving precise edits without double-strand breaks—that significantly expand the potential applications of gene editing in basic research and therapeutic development.

This evolution is critical because no single gene-editing technology is optimal for all applications. The choice of system must be guided by the specific experimental or therapeutic goal, whether it involves knocking down gene expression without altering the genome, targeting RNA viruses, achieving single-base changes with minimal off-target effects, or working within constrained delivery vehicles like adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). This guide provides a systematic comparison of these technologies, focusing on their unique mechanisms, validated applications, and performance metrics to inform selection for research and drug development projects.

Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Applications

Core Mechanisms and Molecular Functions

CRISPR-Cas9: This system utilizes a Cas9 nuclease complexed with a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to create double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA at locations specified by the guide RNA sequence and adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), typically NGG. DNA repair occurs primarily through error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), leading to insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, or less frequently through homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise edits when a donor template is provided [20].

CRISPR-Cas12 (including Cas12f1): Like Cas9, Cas12 proteins target DNA but differ in both structure and mechanism. Cas12 nucleases require only a crRNA for targeting without needing a tracrRNA. Upon binding and cleaving its target DNA, Cas12 exhibits collateral trans-cleavage activity, non-specifically degrading single-stranded DNA molecules in the vicinity. The Cas12f1 variant is particularly notable for its exceptionally small size—approximately half that of Cas9—making it advantageous for viral delivery where packaging capacity is limited [21] [22].

CRISPR-Cas13: In contrast to DNA-targeting Cas proteins, Cas13 is an RNA-guided RNase that specifically targets and cleaves single-stranded RNA (ssRNA). Similar to Cas12, activated Cas13 exhibits collateral RNAse activity, cleaving non-target RNA molecules indiscriminately. This RNA-targeting capability enables transient knockdown of gene expression without permanent genomic alteration, making it particularly valuable for targeting RNA viruses and regulating temporary gene expression [23] [22].

Prime Editing: This system represents a paradigm shift from nuclease-based editing. It employs a Cas9 nickase (H840A) fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme, programmed with a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). The pegRNA both specifies the target site and contains a template for the desired edit. Prime editing directly introduces point mutations, insertions, and deletions without creating double-strand breaks or requiring donor DNA templates, significantly reducing unintended mutations [24] [25].

Table 1: Core Functional Characteristics of Gene-Editing Systems

| System | Target Molecule | Primary Cleavage Activity | Collateral Activity | PAM/PFS Requirement | Editing Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | DNA | Double-strand DNA breaks | None | NGG PAM | Permanent gene disruption via indels |

| Cas12/Cas12f1 | DNA | Single- or double-strand DNA breaks | Trans-ssDNA cleavage | T-rich PAM (TTTV for Cas12) | Gene disruption; diagnostic applications |

| Cas13 | RNA | Single-strand RNA cleavage | Trans-ssRNA cleavage | Protospacer Flanking Site (PFS) | Transient gene knockdown; viral RNA degradation |

| Prime Editing | DNA | Single-strand nick | None | NGG PAM | Precise point mutations, insertions, deletions |

Comparative Performance and Efficiency Metrics

Direct comparisons of editing efficiency between these systems must consider the specific application and target. A 2025 study systematically evaluating the eradication of carbapenem resistance genes (KPC-2 and IMP-4) provides rare direct efficiency data for DNA-targeting systems. When targeting identical regions of these genes, all three systems (Cas9, Cas12f1, and Cas3) demonstrated 100% eradication efficiency in colony PCR assays. However, quantitative PCR revealed significant differences in plasmid copy number reduction, with CRISPR-Cas3 showing the highest eradication efficiency, surpassing both Cas9 and Cas12f1 [21].

For prime editing, efficiency varies substantially based on the specific version and target site. Early systems (PE1) achieved editing frequencies of 10-20% in HEK293T cells, while optimized versions (PE2) reached 20-40%. The most advanced systems (PE3) incorporating additional strand nicks achieve 30-50% efficiency, with more recent iterations (PE4-PE7) reportedly reaching 70-95% for certain targets through suppression of DNA mismatch repair pathways and pegRNA stabilization [24].

Cas13's efficacy is typically measured by viral inhibition or gene knockdown efficiency. Studies demonstrate Cas13 can inhibit 90% of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, and substantially reduce viral loads in human lung epithelial cells infected with influenza H1N1. Against HIV-1, Cas13a showed strong inhibitory effects on viral replication by reducing newly synthesized viral RNA [22].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics Across Applications

| System | Application | Reported Efficiency | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | Antibiotic resistance gene eradication | 100% eradication (colony PCR) | Resensitized resistant E. coli to ampicillin; blocked horizontal transfer (99%) [21] |

| Cas12f1 | Antibiotic resistance gene eradication | 100% eradication (colony PCR) | Lower plasmid copy reduction than Cas3; compact size advantage for delivery [21] |

| Cas13 | SARS-CoV-2 inhibition | ~90% viral inhibition | PAC-MAN technology effectively neutralized SARS-CoV-2 genome [22] |

| HIV-1 suppression | Strong inhibition | Reduced viral gene expression and newly synthesized viral RNA [22] | |

| Prime Editing | Point mutation correction | Up to 95% (PE7) | Versatile editing without double-strand breaks; minimal indels [24] |

Experimental Design and Workflows

Target Selection and Guide RNA Design

Effective gene editing begins with careful target selection and guide RNA design, with specific considerations for each system:

Cas9 Guide Design: Select a 20-30 nucleotide sequence immediately upstream of an NGG PAM motif. The spacer should be evaluated for potential off-target sites with similar sequences. Tools like CRISPR_HNN leverage hybrid deep neural networks to predict on-target activity based on local features and cross-sequence dependencies [26].

Cas12f1 Guide Design: Design involves selecting a 20-nucleotide sequence upstream of a TTTN PAM motif. The smaller size of Cas12f1 requires optimization for efficient folding and function within confined spaces [21].

Cas13 Guide Design: The system identifies target RNA sequences with a specific protospacer flanking sequence (PFS) requirement, though this is less restrictive than DNA-targeting PAMs. Guide RNAs should target conserved regions of viral RNA genomes for antiviral applications [23].

Prime Editing pegRNA Design: The pegRNA includes both a spacer sequence for target recognition and a reverse transcriptase template (RTT) encoding the desired edit. The primer binding site (PBS) must be optimized for efficient priming of reverse transcription. Recent advances like engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) improve stability and editing efficiency [24] [25].

For researchers comparing multiple Cas9 variants with different PAM requirements, bioinformatic tools like CATS (Comparing Cas9 Activities by Target Superimposition) automate the detection of overlapping PAM sequences and identify allele-specific targets, particularly useful for targeting pathogenic mutations in dominant disorders [27].

Delivery Methods and Experimental Workflows

Delivery methods vary based on the application and target cell type:

Plasmid-Based Delivery: For bacterial systems, such as eradication of antibiotic resistance genes, recombinant CRISPR plasmids are transformed into competent cells using standard heat-shock or electroporation methods. For the KPC-2 and IMP-4 eradication study, researchers transformed recombinant CRISPR plasmids into Escherichia coli carrying resistance plasmids using commercially available competent cell preparation kits [21].

Viral Delivery: Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are commonly used for mammalian cell delivery, though their limited packaging capacity (~4.7 kb) favors smaller editors like Cas12f1. Lentiviral systems can accommodate larger constructs but integrate into the genome.

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): For in vivo therapeutic applications, LNPs have emerged as a promising delivery vehicle, particularly for liver-targeted therapies. LNPs facilitate redosing potential—as demonstrated in clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) where participants received multiple doses—unlike viral vectors which often trigger immune responses preventing re-administration [14].

Diagram 1: Generalized Experimental Workflow for CRISPR-Based Editing. The process involves three main phases: target selection and guide design, delivery method selection and implementation, and validation of editing outcomes through molecular and functional assays.

Research Applications and Therapeutic Prospects

Antimicrobial Applications

The rise of antibiotic-resistant pathogens has stimulated development of CRISPR-based antimicrobials:

Resistance Plasmid Eradication: CRISPR systems effectively eliminate antibiotic resistance genes located on bacterial plasmids. In proof-of-concept studies, Cas9, Cas12f1, and Cas3 all successfully eradicated carbapenem resistance genes (KPC-2 and IMP-4) from E. coli, restoring sensitivity to ampicillin and blocking horizontal transfer of resistance plasmids with up to 99% efficiency [21].

Sequence-Specific Bacterial Killing: Cas13a demonstrates potent bactericidal activity when targeting essential genes in drug-resistant bacteria. The system shows superiority over Cas9-based antimicrobials, particularly when targeting genes located on plasmids. Engineered CapsidCas13a nucleocapsids specifically kill carbapenem-resistant E. coli and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) by identifying corresponding antimicrobial resistance gene sequences [22].

Antiviral Therapeutics

Cas13's RNA-targeting capability positions it as a promising antiviral platform:

Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Approach: The PAC-MAN (Prophylactic Antiviral CRISPR in human cells) strategy combines Cas13 with guide RNAs targeting conserved regions of viral genomes. This approach effectively neutralized SARS-CoV-2 and reduced influenza H1N1 viral load in human lung epithelial cells [22].

HIV-1 Inhibition: Cas13a strongly inhibits HIV-1 infection in human cells by targeting viral RNA for degradation, reducing both viral gene expression and newly synthesized viral RNA. The system can target viral RNA entering cells within the viral capsid, providing early intervention in the viral lifecycle [22].

Therapeutic Delivery: AAV-delivered Cas13 effectively targets and eliminates human enterovirus in both cells and infected mice, functioning as both a prophylactic and therapeutic agent against lethal RNA viral infections [22].

Genetic Disease Correction

Precision editing systems offer new avenues for correcting disease-causing mutations:

Prime Editing for Genetic Disorders: Prime editing's ability to make precise corrections without double-strand breaks makes it ideal for addressing monogenic disorders. Early versions have been succeeded by more efficient systems (PE2, PE3), with recent iterations (PE4-PE7) achieving dramatically higher efficiencies through suppression of DNA mismatch repair and pegRNA stabilization [24].

RNA-Targeting for Neurological Disorders: Cas13-based approaches successfully reduce mutant protein production in mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington's disease by targeting and degrading RNA transcripts without altering genomic DNA. Similarly, mini-dCas13X-mediated RNA editing restored dystrophin expression in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy [22].

In Vivo Therapeutic Success: Clinical trials demonstrate the therapeutic potential of CRISPR systems. For hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), a Cas9-based therapy delivered via lipid nanoparticles achieved ~90% reduction in disease-related protein levels, with effects sustained over two years. Similarly, a treatment for hereditary angioedema (HAE) resulted in 86% reduction in kallikrein protein and significantly reduced inflammation attacks [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for CRISPR Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Plasmids | Source of Cas proteins | pCas9 (Addgene #42876), pCas3 (Addgene #133773), pCas12f1 [21] |

| Guide RNA Cloning Vectors | Template for sgRNA expression | BsaI restriction sites for cloning; U6 promoters for mammalian expression [21] |

| Prime Editing Plasmids | All-in-one prime editor systems | PE2, PE3 systems; nCas9(H840A)-reverse transcriptase fusions [24] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Introducing editors into cells | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for in vivo delivery; AAV for viral delivery; chemical transformation for bacteria [21] [14] |

| Target-Specific Guides | Sequence-specific targeting | 30nt spacers for Cas9; 20nt for Cas12f1; 34nt for Cas3; pegRNAs for prime editing [21] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Design and optimization | CATS for PAM comparison; CRISPR_HNN for on-target prediction; CRISPOR for guide design [26] [27] |

| Efficiency Reporters | Measuring editing outcomes | PEAR plasmid (fluorescent reporter); antibiotic sensitivity testing; qPCR for copy number [21] [25] |

The expanding CRISPR toolkit offers researchers multiple specialized options for genetic manipulation, each with distinct advantages and optimal applications. Cas9 remains the workhorse for straightforward gene disruption but faces limitations in size and precision. Cas12f1 provides a compact alternative valuable for delivery-constrained applications. Cas13 opens the unique capability of targeting RNA molecules, enabling transient knockdown and antiviral strategies without genomic alteration. Prime editing represents the current pinnacle of precision, offering versatile editing capabilities with minimal collateral damage.

Selection criteria should prioritize:

- Target molecule (DNA vs. RNA)

- Required precision (disruption vs. precise correction)

- Delivery constraints (size limitations)

- Persistence needs (permanent vs. transient effects)

- Safety profile concerns (off-target effects)

As clinical applications advance—with demonstrated success in treating genetic disorders like sickle cell disease, hATTR, and HAE—the strategic selection of appropriate editing technologies becomes increasingly critical. Future directions will likely focus on enhancing delivery efficiency, expanding targeting scope, and improving safety profiles through novel engineered variants and refined computational design tools.

Strategic Implementation: Matching Cas Variants to Therapeutic Applications

The clinical advancement of CRISPR-based gene therapies is fundamentally constrained by the efficient delivery of editing machinery into target cells. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors have emerged as a leading delivery vehicle due to their favorable safety profile, high tissue specificity, and ability to sustain long-term transgene expression. However, a significant limitation is their constrained packaging capacity of approximately 4.7 kilobases (kb), which is insufficient for the coding sequence of the widely used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9, ~4.2 kb) when combined with essential regulatory elements [28] [29]. This bottleneck has driven the exploration and development of compact Cas protein alternatives, notably Staphylococcus aureus* Cas9 (SaCas9) and various Cas12f variants, which are small enough to be packaged alongside their guide RNAs into a single AAV vector. This guide provides a objective comparison of these AAV-compatible Cas proteins, focusing on their molecular characteristics, editing performance, and practical application in therapeutic contexts.

Molecular and Biophysical Properties

The primary advantage of small Cas proteins is their size, which directly addresses the AAV packaging limitation. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of SaCas9 and Cas12f in comparison to the standard SpCas9.

Table 1: Molecular Characteristics of Compact Cas Proteins Compared to SpCas9

| Feature | SpCas9 | SaCas9 | Cas12f |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Streptococcus pyogenes | Staphylococcus aureus | Uncultured archaeon (e.g., Un1Cas12f1) |

| Size (amino acids) | ~1,368 [8] | 1,053 [30] [8] | 529 [31] |

| Gene Size (kb) | ~4.2 [29] | ~3.2 [29] | ~1.5-1.6 [32] [29] |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' [8] | 5'-NNGRRT-3' [30] [8] | Varies by specific variant |

| AAV Packaging | Requires dual or split systems [29] | Compatible in a single vector [28] [30] | Highly compatible in a single vector [28] |

| Reported Editing Efficiency | High, but delivery-limited | High in mouse zygotes (e.g., 77.7-94.1%) [30] | Lower than Cas9, but enhanced by engineering [31] |

The compact dimensions of SaCas9 and Cas12f not only facilitate simpler single-vector AAV delivery but also influence their biophysical behavior. A comparative study of cellular uptake demonstrated that Cas12f ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes formed particles with a hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 250 nm, significantly smaller than Cas9 RNP complexes which measured about 1100 nm. This smaller size contributed to more efficient cellular penetration and delivery [32].

Performance and Efficiency Comparison

Editing Efficiency and Specificity

While small in size, these compact nucleases must maintain high editing activity to be therapeutically relevant.

- SaCas9 has demonstrated robust efficiency in genome editing. A study in mouse zygotes showed that SaCas9 could disrupt target genes with high efficacy, ranging from 77.7% to 94.1% in born pups, a performance comparable to SpCas9 in the same study [30]. Deep sequencing of founder mice revealed no detectable off-target edits at the top ten predicted sites, indicating high specificity [30].

- Cas12f has historically suffered from suboptimal editing activity compared to SpCas9 and SaCas9 [31]. However, recent protein and guide RNA engineering efforts have led to substantial improvements. For instance, one study demonstrated that engineered circular guide RNAs (cgRNAs) could enhance Cas12f-based gene activation by 1.9 to 19.2-fold in human cells [31]. When this optimized system was combined with a phase separation domain, activation efficiency was further increased by 2.3 to 3.9-fold [31].

In Vivo Therapeutic Efficacy

Both nucleases have shown promise in preclinical animal models, delivered via AAV vectors.

- SaCas9: Its efficacy has been validated in multiple disease models. For example, AAV8 vectors delivering SaCas9 with liver-specific promoters have been used to inhibit hepatitis B virus replication [8].

- Cas12f: The hypercompact size of Cas12f makes it exceptionally suitable for all-in-one AAV strategies. A prime example is the use of an rAAV8 vector encoding a compact CasMINI_v3.1 (a derived Cas12f variant) to target the Nr2e3 gene in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. This approach achieved over 70% transduction efficiency in retinal cells and led to a significant improvement in photoreceptor function one month post-injection [28].

Table 2: Summary of Key Preclinical In Vivo Studies

| Cas Protein | Disease Model | Delivery Method | Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SaCas9 | Mouse zygotes (gene knockout) | Microinjection of mRNA/gRNA | High efficiency (up to 94.1%) in generating mutant mice | [30] |

| Cas12f (CasMINI) | RhoP23H/+ mouse (Retinitis Pigmentosa) | rAAV8 subretinal injection | >70% transduction; improved cone function | [28] |

| EnIscB (Cas ancestor) | Mouse model of Tyrosinemia | rAAV8 systemic delivery | 15% editing efficiency; restoration of Fah expression | [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Evaluation

To objectively compare the performance of different Cas variants, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies commonly cited in the literature for assessing delivery and editing efficiency.

Protocol 1: Evaluating Cellular Uptake of Cas RNP Complexes

This protocol, adapted from a comparative study of Cas12f and Cas9, is used to quantify the cellular internalization efficiency of RNP complexes delivered via non-viral carriers [32].

- RNP Complex Formation: Incubate recombinant Cas protein (e.g., Cas9 or Cas12f) with a synthetic guide RNA that is fluorescently labeled (e.g., with ATTO550) at a molar ratio of 1:1.1 for 10 minutes at the protein's optimal temperature (25°C for Cas9, 45°C for Cas12f) [32].

- Complexation with Delivery Vector: Mix the formed RNPs with a transfection vehicle, such as the amphipathic peptide PepFect14 (PF14). Vortex immediately and incubate for 40 minutes at room temperature to form stable RNP/vector complexes [32].

- Cell Transfection: Seed adherent cells (e.g., HEK293T) in a 96-well plate. Add the RNP/vector complexes to the cells and incubate [32].

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: At specified time points post-transfection (e.g., 6 and 24 hours), harvest the cells. Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer equipped with an appropriate fluorescence filter (e.g., PE-CF594). Quantify uptake as the percentage of fluorescent-positive cells and the mean fluorescence intensity ratio, which indicates the amount of RNP internalized [32].

Experimental workflow for evaluating RNP cellular uptake.

Protocol 2: Assessing In Vivo Gene Editing with AAV Delivery

This protocol outlines the steps for evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of an AAV-delivered compact Cas system in a mouse model.

- Vector Design and Production: Clone the gene for the compact Cas protein (e.g., SaCas9 or Cas12f) and its corresponding gRNA expression cassette into an AAV plasmid. Select an appropriate serotype (e.g., AAV8 for liver, AAV9 for broad tropism) and produce the recombinant AAV vectors [28].

- Animal Injection: Administer the AAV vectors to the target animal model. The route of administration depends on the target tissue:

- Tissue Collection and Analysis: After a predetermined period (e.g., 4-8 weeks), harvest the target tissues.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from the tissue.

- Editing Efficiency Analysis: Amplify the target genomic region by PCR and sequence the products using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to precisely quantify the percentage of insertions and deletions (indels) [30].

- Functional Assessment: Perform immunohistochemistry or Western blot to detect the restoration of a functional protein (e.g., FAH in a tyrosinemia model) and evaluate physiological or behavioral recovery relevant to the disease [28].

Workflow for in vivo gene editing assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimentation with compact Cas proteins requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for such studies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for AAV-Compatible Cas Protein Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Compact Cas Expression Plasmid | Provides the genetic template for Cas protein production. | Plasmids for SaCas9 [30] or Cas12f (e.g., Addgene #171613) [32]. |

| AAV Transfer Plasmid | Backbone for packaging Cas and gRNA into AAV particles. | Must include ITRs; chosen serotype dictates tissue tropism (e.g., AAV8, AAV9) [28] [29]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Directs the Cas protein to the specific DNA target sequence. | Synthetic sgRNAs or plasmids with U6/H1 promoters [29]. Engineered circular gRNAs (cgRNAs) enhance Cas12f stability and efficiency [31]. |

| Delivery Vectors | Facilitates entry of CRISPR components into cells. | In vitro: Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX, PepFect14 (PF14) peptide [32]. In vivo: Recombinant AAV particles [28]. |

| Cell Lines | Model systems for in vitro testing. | HEK293T [32] [31], reporter cell lines for activation studies [31], and disease-relevant primary cells. |

| Animal Models | For in vivo efficacy and safety testing. | Mouse models of human diseases (e.g., tyrosinemia [28], retinitis pigmentosa [28]). |

| Analysis Tools | For quantifying editing outcomes. | NGS platforms for indel analysis [30], T7 Endonuclease I assay [30], flow cytometry for uptake/activation [32] [31]. |

The constrained packaging capacity of AAV vectors presents a significant barrier to CRISPR-Cas therapy development, which is effectively addressed by compact Cas proteins like SaCas9 and Cas12f. SaCas9 stands out for its robust and well-characterized nuclease activity, demonstrated across multiple in vivo models. In contrast, Cas12f, with its ultra-compact size, offers superior delivery flexibility and has shown remarkable therapeutic potential in recent studies, particularly when combined with engineered guide RNAs. The choice between these alternatives involves a balanced consideration of the target genomic sequence, required editing efficiency, and delivery constraints. Ongoing protein engineering efforts are rapidly enhancing the efficiency, precision, and versatility of both systems, solidifying their role as indispensable tools for the future of in vivo genomic medicine.

The CRISPR-Cas system has revolutionized genome engineering, with Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) long serving as the foundational tool for gene knockout experiments. However, SpCas9 presents significant limitations including off-target effects, large size complicating delivery, and restrictive PAM requirements that limit targeting scope [8]. To overcome these challenges, the field has advanced several high-efficiency nuclease alternatives, with Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9) and various Cas12a variants emerging as particularly powerful for gene knockout applications.

SaCas9 offers a distinct advantage with its compact size (1053 amino acids), enabling efficient packaging into adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors for therapeutic delivery [8]. Cas12a (formerly Cpf1) represents a fundamentally different CRISPR system with staggered DNA cleavage and T-rich PAM recognition, expanding the targetable genome space [33]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these high-efficiency nucleases, presenting objective performance data and optimized experimental protocols to inform researcher selection for specific gene knockout applications.

Comparative Analysis of Nuclease Properties and Performance

Molecular Characteristics and Targeting Capabilities

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of High-Efficiency CRISPR Nucleases

| Property | SpCas9 | SaCas9 | Cas12a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Streptococcus pyogenes | Staphylococcus aureus | Type V-A CRISPR systems |

| Size (aa) | 1368 [34] | 1053 [8] [34] | ~1100-1300 (varies by ortholog) |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' [8] | 5'-NNGRRT-3' [8] [34] | 5'-TTTN-3' [33] |

| Cleavage Pattern | Blunt ends [8] | Blunt ends [8] | Staggered ends with 5' overhangs [33] |

| gRNA Structure | crRNA + tracrRNA [8] | crRNA + tracrRNA [8] | Single crRNA [33] |

| Targeting Frequency | Every 8 bp [34] | Every 32 bp [34] | Varies by genomic AT content |

Editing Efficiency and Precision Comparison

Table 2: Performance Comparison of SaCas9 versus SpCas9 in Human Cells

| Performance Metric | SpCas9 | SaCas9 | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Indel Efficiency | Lower at most sites | Higher at 11 tested loci [34] | Human iPSCs and K562 cells |

| Optimal Spacer Length | 20 nt (range: 18-21 nt) [34] | 21 nt (range: 21-22 nt) [34] | Systematic testing of spacer lengths |

| HDR-Mediated Knock-in Efficiency | Lower | Higher [34] | AAV6 donor delivery in human cells |

| NHEJ +1 Insertion Bias | Substantial | Reduced [34] | Characterized editing outcomes |

| Off-target Effects | Higher | Significantly reduced [34] | GUIDE-seq analysis |

Recent rigorous comparison studies demonstrate that SaCas9 achieves higher editing efficiencies than SpCas9 across multiple genomic loci in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and K562 cells [34]. The optimal spacer length differs between systems, with SaCas9 performing best with 21-nt spacers compared to 20-nt for SpCas9 [34]. Importantly, SaCas9 exhibits significantly reduced off-target effects while maintaining robust on-target activity, making it particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where precision is paramount [34].

Cas12a offers distinct advantages for targeting AT-rich genomic regions due to its T-rich PAM requirement [33]. Engineered Cas12a variants such as hfCas12Max demonstrate enhanced editing capabilities with reduced off-target effects [8]. With approximately 1080 amino acids, hfCas12Max maintains a small size compatible with viral delivery while recognizing a broad PAM sequence (5'-TN-3') that significantly expands targetable genome space [8].

Optimized Experimental Protocols

gRNA Design and Validation

Achieving high-efficiency gene knockout requires optimized gRNA design specific to each nuclease platform:

For SaCas9 Applications:

- Design gRNAs with 21-22 nucleotide spacers for maximum activity [34]

- Utilize the 3TC scaffold modification (replacing the fourth T in the tetraloop with C) to enhance gRNA transcript levels, particularly important for T-rich gRNA sequences [35]

- Select targets with NNGRRT PAM sequences, preferably NNGGAT for highest efficiency [34]

For Cas12a Applications:

- Design crRNAs with consideration for nucleotide bias near the PAM site, as this significantly influences cleavage efficiency [33]

- Account for the staggered cut pattern which creates 5' overhangs rather than blunt ends when designing knockout strategies [33]

Figure 1: gRNA Design and Optimization Workflow. The 3TC scaffold modification is particularly beneficial for T-rich gRNAs and when vector availability is limited [35].

Delivery and Expression Optimization

Enhanced Nuclear Localization: For SaCas9, fusion with HMGA2 and bipartite NLS (BPNLS) significantly improves editing efficiency. Research demonstrates that HMGA2-SaCas9-BPNLS constructs increase editing efficiency by approximately 30% compared to standard NLS configurations [34].

Transcript Level Optimization: Under limited vector availability conditions, modifying the gRNA scaffold to 3TC provides dramatic improvements in gRNA transcript levels and subsequent editing efficiency [35]. This optimization is compatible with both SaCas9 and SpCas9 systems and is particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where delivery efficiency is constrained.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery: For both SaCas9 and Cas12a, RNP delivery offers advantages including rapid onset of action, reduced off-target effects, and elimination of plasmid integration risk [36]. RNP delivery also enables use of chemically modified gRNAs with improved stability and reduced cellular toxicity [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High-Efficiency Gene Knockout Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Expression Plasmids | HMGA2-SaCas9-BPNLS [34] | Enhanced nuclear localization and editing efficiency |

| Optimized gRNA Scaffolds | 3TC scaffold (T4>C mutation) [35] | Increased gRNA transcript levels by reducing Pol III termination |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV vectors for SaCas9 [8], Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [14] | Efficient in vivo delivery compatible with smaller Cas variants |

| HDR Donor Templates | ssODNs with 40-nt homology arms [36] | Precise editing when combined with HDR-based knockout strategies |

| Editing Enhancers | MLH1dn for prime editing systems [24] | Suppresses mismatch repair to increase editing efficiency |

Advanced Applications and Therapeutic Translation

The compact size of SaCas9 has enabled its use in AAV-mediated in vivo gene editing for neurological research, liver-directed therapies, and muscular disorders [8]. For instance, SaCas9 delivered via AAV8 with liver-specific promoters successfully inhibited hepatitis B virus replication in preclinical models [8].

Cas12a-based editors are advancing toward clinical applications, with hfCas12Max being developed as HG302 for Duchenne muscular dystrophy treatment [8]. The small size of Cas12f variants (approximately 850 amino acids) further expands delivery options while maintaining high editing efficiency [37].

Recent clinical advances include the first personalized in vivo CRISPR treatment for an infant with CPS1 deficiency, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of LNP-del editors [14]. Additionally, the ability to redose LNP-delivered editors (as demonstrated in trials for hATTR amyloidosis) provides significant clinical flexibility not possible with viral delivery methods [14].

SaCas9 and Cas12a nucleases represent powerful alternatives to traditional SpCas9 for gene knockout applications. SaCas9 offers superior editing efficiency and enhanced specificity in a compact size compatible with AAV delivery [34]. Cas12a variants expand the targetable genomic space with their T-rich PAM requirements and demonstrate high fidelity in therapeutic development [8] [33].

Selection between these platforms should be guided by specific experimental needs: SaCas9 for applications requiring maximal efficiency and precision in a compact form factor, and Cas12a variants for targeting AT-rich regions or when staggered cuts are advantageous. Implementation of the optimized experimental protocols outlined in this guide, particularly regarding gRNA scaffold modifications and enhanced localization signals, will enable researchers to maximize knockout efficiency in their specific experimental systems.

The advent of precision genome editing has revolutionized genetic research and therapeutic development by enabling targeted correction of point mutations, which account for a significant proportion of known genetic disorders. Unlike early nuclease-based technologies such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) that rely on creating double-strand breaks (DSBs), newer precision editing modalities offer more controlled and safer approaches for genetic modifications [38] [7]. Among these, base editing and prime editing have emerged as transformative technologies that facilitate precise nucleotide changes without inducing DSBs, thereby minimizing unwanted genetic outcomes such as insertions, deletions (indels), and chromosomal rearrangements [39] [40].

Base editing, introduced in 2016, utilizes a catalytically impaired CRISPR-Cas system fused to a deaminase enzyme to directly convert one DNA base into another [40]. While efficient for specific transition mutations, this approach is limited to four of the twelve possible base-to-base conversions and operates within a narrow editing window [41] [42]. To overcome these limitations, prime editing was developed in 2019 as a more versatile "search-and-replace" technology that uses a Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion protein programmed with an extended guide RNA to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site [41] [39]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these precision editing modalities, with particular emphasis on the evolving prime editing systems (PE2, PE3, PE4) and their application for correcting point mutations.

Technical Mechanisms and Editor Evolution

Base Editing Architecture and Limitations

Base editors consist of a catalytically impaired Cas9 protein (nCas9) fused to a deaminase enzyme, which enables direct chemical conversion of nucleobases without generating DSBs [40]. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) convert cytosine (C) to thymine (T), while adenine base editors (ABEs) convert adenine (A) to guanine (G) [39] [40]. These editors function within a defined editing window typically spanning 4-5 nucleotides, where the deamination activity occurs [39]. While base editing achieves high efficiency for specific transition mutations—often exceeding 50% in cultured mammalian cells—it cannot perform transversion mutations (e.g., C to G, C to A, A to T, A to C) or more complex edits such as targeted insertions and deletions [42] [39]. Additionally, base editors can cause bystander edits, where multiple bases within the editing window are modified, resulting in heterogeneous editing products [41] [39].

Prime Editing: A Versatile Search-and-Replace System

Prime editing represents a significant advancement in precision editing by overcoming key limitations of base editing. The core prime editing system consists of two primary components: (1) a prime editor protein, which is a fusion of a Cas9 nickase (H840A mutation) and a reverse transcriptase (RT) domain; and (2) a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit [41] [39] [40]. The editing mechanism occurs through a multi-step process: first, the Cas9 nickase cleaves the DNA strand containing the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), exposing its 3' end hydroxyl group; this exposed end then hybridizes with the primer binding site (PBS) on the pegRNA, serving as a primer for the RT to synthesize new DNA containing the desired edit using the reverse transcriptase template (RTT) [42] [39]. The resulting heteroduplex DNA, with one edited strand and one unedited strand, is then resolved by cellular repair mechanisms to incorporate the edit permanently [41].

Table 1: Core Components of Prime Editing Systems

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nickase | Cas9 with H840A mutation that cleaves only one DNA strand | Creates an initiation point for reverse transcription without generating DSBs |

| Reverse Transcriptase (RT) | Engineered Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) RT | Synthesizes DNA using the pegRNA template to incorporate edits |

| pegRNA | Extended guide RNA with target sequence, RT template, and primer binding site | Specifies target locus and encodes desired genetic modification |

Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

The development of prime editing has progressed through several generations, each offering improved efficiency and specificity. The original system, PE1, fused the wild-type M-MLV RT to Cas9 nickase and demonstrated the fundamental capability to perform diverse edits but with modest efficiency (0.7-5.5% for point mutations) [41] [42]. PE2 incorporated an engineered reverse transcriptase with five mutations that enhanced thermostability, processivity, and DNA-RNA hybridization affinity, improving editing efficiency by 2.3- to 5.1-fold compared to PE1 [41]. PE3 further increased efficiency by incorporating an additional sgRNA that nicks the non-edited strand to encourage the cell to use the edited strand as a repair template, boosting efficiency 2-3-fold, though with a slight increase in indel formation [41] [39]. To address this, PE3b was developed with a strand-selective nick sgRNA that reduces indels by 13-fold compared to PE3 [41].

The most recent advancements include PE4 and PE5 systems, which incorporate a dominant-negative mutant of the MLH1 protein, a key component of the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway [41]. By temporarily inhibiting MMR, these systems prevent the reversal of edits and improve efficiency by 7.7-fold (PE4 versus PE2) and 2.0-fold (PE5 versus PE3) [41]. Further optimization led to PEmax, an improved editor with codon-optimized RT, additional nuclear localization signals, and mutations that enhance nuclease activity [41]. Most recently, PE6 systems have been developed with evolved RT domains from various sources (e.g., E. coli Ec48 retron RT, S. pombe Tf1 retrotransposon RT) to enhance efficiency, particularly for complex edits [41].

Figure 1: Evolution of prime editing systems from PE1 to PE6, highlighting key innovations at each stage that enhanced editing efficiency and specificity. MMR = mismatch repair; NLS = nuclear localization signals; RT = reverse transcriptase.

Comparative Performance Analysis for Point Mutations

Editing Capabilities and Specificity

When comparing base editing and prime editing for point mutation correction, each system offers distinct advantages and limitations. Base editors excel at installing transition mutations (C→T, G→A, A→G, T→C) within their activity window with high efficiency (often >50%) and minimal indels [41] [40]. However, they cannot perform transversion mutations (e.g., C→G, C→A, T→A, T→G) and often create bystander edits when multiple targetable bases fall within the editing window [41] [39]. In contrast, prime editing supports all 12 possible base-to-base conversions with greater precision and no bystander activity, as the edit is explicitly defined by the pegRNA template [41] [40]. While prime editing initially showed variable efficiency (1-20% in early systems), recent optimizations have achieved efficiencies up to 53.2% in human cells [42].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Base Editing vs. Prime Editing for Point Mutations

| Parameter | Base Editing | Prime Editing (PE2-PE4) |

|---|---|---|

| Point Mutation Types | 4 transition mutations (C→T, G→A, A→G, T→C) | All 12 possible base-to-base conversions |

| Typical Efficiency | High (often >50%) for targets within editing window | Variable (1-50+%), highly dependent on target site and optimization |

| Bystander Editing | Common when multiple editable bases are in window | None - edits are specific to pegRNA template |

| Indel Formation | Very low (<1%) | Low (1-10% in PE3, reduced in PE4/PE5) |

| PAM Flexibility | Limited by Cas9 variant (typically NGG for SpCas9) | More flexible editing distance from PAM (up to 30+ bp) |

| Theoretical Scope | ~30% of known pathogenic SNVs | ~90% of known pathogenic SNVs |

Efficiency Across Editing Contexts

The efficiency of both base editing and prime editing varies significantly depending on genomic context, cell type, and the specific mutation being introduced. Base editing efficiency is highly dependent on the positioning of the target base within the editing window and the sequence context, with optimal performance when the target base is centrally located within the window [41]. Prime editing efficiency depends on multiple factors including the length of the reverse transcriptase template and primer binding site, the type of edit being made, and the genomic target site [41] [40]. For positions well-positioned within the base editing window, base editing generally achieves higher efficiency with fewer byproducts than prime editing; however, for targets with suboptimal positioning or requiring transversion mutations, prime editing becomes the preferred option despite potentially lower absolute efficiency [41].

Recent studies directly comparing these technologies at identical sites have demonstrated that base editing typically achieves higher editing rates (often 2-5 times higher) for transition mutations within its activity window [41]. However, prime editing achieves more precise outcomes without bystander edits, making it preferable when single-base precision is required. For example, in experiments correcting the sickle cell disease mutation (T∙A-to-A∙T transversion) in the HBB gene, prime editing successfully achieved correction while base editing was incapable of installing this change [42].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Prime Editing Workflow for Point Mutation Correction

Implementing prime editing for point mutation correction requires careful experimental design and optimization. A standard workflow begins with identifying the target mutation and designing pegRNAs with appropriate reverse transcriptase templates (typically 10-16 nucleotides for point mutations) and primer binding sites (typically 8-15 nucleotides) [41] [40]. The pegRNA should be designed to place the edit at an optimal position within the template, typically closer to the nick site for higher efficiency. For improved stability and performance, engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) incorporating RNA pseudoknots at the 3' end can be used to protect against degradation [41] [39].

The experimental protocol involves delivering the prime editor components (editor protein or mRNA and pegRNA) to target cells using appropriate methods such as lipid nanoparticles, electroporation, or viral vectors [40]. For PE2 systems, only the prime editor and pegRNA are delivered; for PE3 systems, an additional nicking sgRNA is included to enhance efficiency [41] [39]. For maximal efficiency with minimal indels, PE4/PE5 systems combining the prime editor with MMR inhibition (e.g., MLH1dn) are recommended [41]. Editing efficiency is typically assessed 48-72 hours post-delivery using next-generation sequencing of PCR-amplified target regions, with careful analysis of both intended edits and potential byproducts.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for prime editing implementation, highlighting key steps from pegRNA design to outcome analysis, with optimization strategies at each stage.

Quantitative Assessment of Editing Outcomes

Rigorous quantification of editing outcomes is essential for comparing different editing approaches. Next-generation sequencing of target loci remains the gold standard for assessing editing efficiency, specificity, and byproduct formation [41] [43]. For base editing experiments, analysis should quantify the percentage of desired base conversion while monitoring for bystander edits at adjacent positions. For prime editing, assessment should include measurement of desired edit incorporation, presence of indels, and potential pegRNA-derived sequences that may be inadvertently inserted [41].

When comparing PE2, PE3, and PE4 systems, studies have consistently shown a progression of improved efficiency: PE2 typically achieves 1-20% editing depending on the target site, PE3 increases this by 2-3-fold, and PE4/PE5 systems further enhance efficiency by approximately 7.7-fold over PE2 while reducing undesired indels [41]. For example, in experiments editing the HEK3 and HEK4 loci in HEK293T cells, PE2 achieved 17-21% efficiency, PE3 increased this to 32-55%, while PE5 (PE3 with MMR inhibition) achieved optimal balance of high efficiency (up to 53%) with reduced indels (1.2-2.5%) [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of precision editing requires access to specialized reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential research reagents for base editing and prime editing experiments, along with their specific functions in the editing workflow.