CRISPR vs. TALENs vs. ZFNs: A 2025 Specificity and Application Comparison for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date comparison of the specificity of the three primary genome-editing platforms: CRISPR, TALENs, and ZFNs.

CRISPR vs. TALENs vs. ZFNs: A 2025 Specificity and Application Comparison for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date comparison of the specificity of the three primary genome-editing platforms: CRISPR, TALENs, and ZFNs. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental mechanisms that dictate precision, delves into current therapeutic and research applications, and addresses key challenges like off-target effects. The content synthesizes the latest 2025 clinical data and technological advancements, including base editing and AI-driven design, to offer a clear, evidence-based framework for selecting the optimal tool for specific research and clinical goals.

Understanding the Core Mechanisms: How CRISPR, TALENs, and ZFNs Achieve Specificity

The field of genome engineering has been revolutionized by technologies that enable precise modifications to DNA sequences. These tools can be fundamentally categorized by their targeting mechanisms: those that rely on protein-DNA interactions and those that utilize RNA-guided DNA recognition [1] [2]. Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) belong to the first category, where engineered proteins directly bind to specific DNA sequences. In contrast, the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system represents the latter, using a guide RNA molecule to direct a nuclease to its DNA target [3] [2]. This fundamental distinction in targeting philosophy has profound implications for the design, specificity, efficiency, and application of these technologies in research and therapy. This guide provides an objective comparison of these systems, focusing on their performance and the experimental data that defines their capabilities.

Protein-DNA Interaction Systems

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) were among the first programmable genome editing tools. Their design involves fusing a engineered zinc finger DNA-binding domain to the FokI nuclease domain [1] [4]. Each zinc finger module typically recognizes a 3-base pair sequence, and arrays of multiple fingers are assembled to create a protein that binds a specific 9-18 bp sequence [1]. Because the FokI nuclease must dimerize to become active, a pair of ZFNs is required to bind opposite strands of DNA, with their cleavage sites facing each other across a short spacer region [1].

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) operate on a similar principle but use a different DNA-binding architecture derived from TALE proteins in Xanthomonas bacteria [1] [5]. The DNA-binding domain of a TALEN consists of a series of 33-35 amino acid repeats, each recognizing a single base pair through two hypervariable amino acids known as Repeat Variable Diresidues (RVDs) [1] [5]. Common RVDs include NI for adenine, HD for cytosine, NN for guanine/adenine, and NG for thymine [5]. Like ZFNs, TALENs also use the FokI nuclease domain and require pairing for activity.

RNA-Guided Systems

The CRISPR-Cas system represents a paradigm shift from protein-based targeting. This system originates from a prokaryotic adaptive immune mechanism that protects bacteria from viral infections [2] [6]. The most widely used variant, CRISPR-Cas9, consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [2]. The gRNA is a synthetic fusion of two natural RNAs—crRNA and tracrRNA—and contains a ~20 nucleotide sequence that is complementary to the target DNA site [2]. Cas9 is directed to the target DNA by RNA-DNA base pairing, and requires a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site for recognition [2]. For Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, the PAM is 5'-NGG-3' [2].

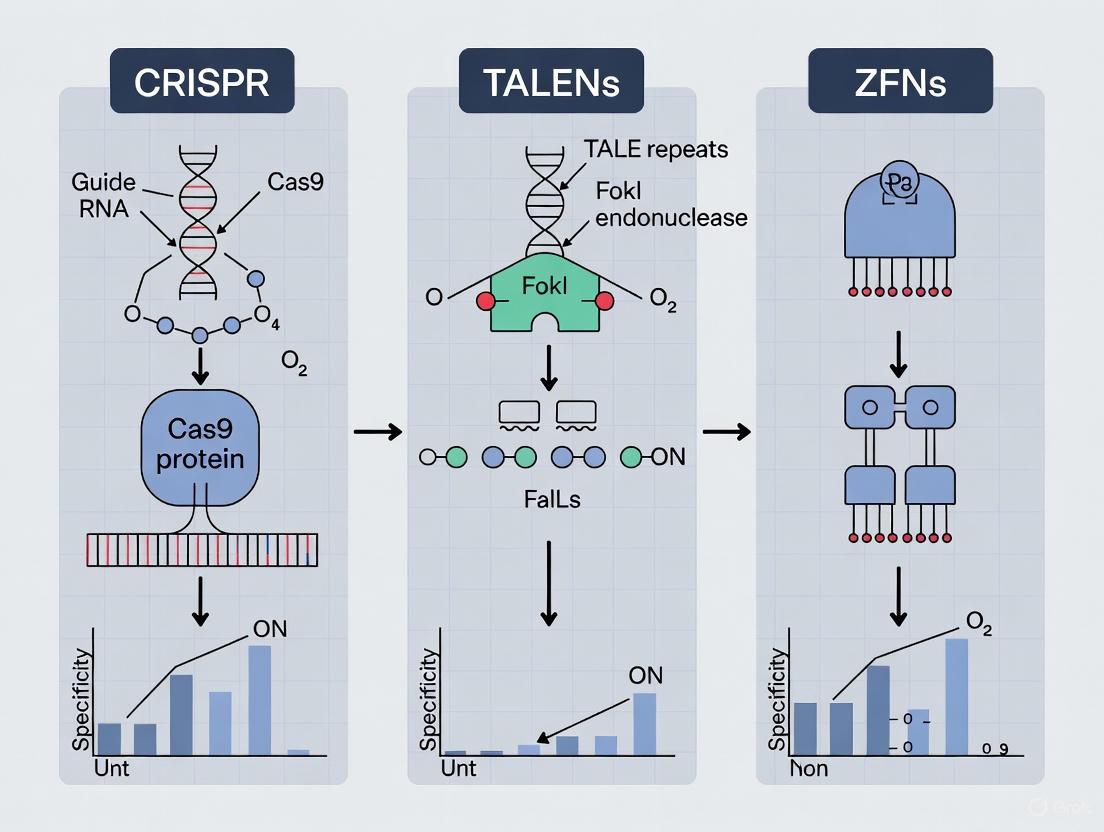

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences in how these three systems locate and bind their DNA targets.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Specificity and Off-Target Effects

Specificity—the ability to edit only the intended target—is a critical parameter for evaluating genome editing tools. Each technology has distinct strengths and limitations in this regard.

TALENs are renowned for their high specificity, which stems from their long, highly specific DNA-binding domains (typically 30-40 bp per TALEN pair) and the requirement for dimerization of FokI nuclease [3]. Research has shown that TALEN specificity can be further enhanced by using non-conventional RVDs (ncRVDs) that improve discrimination between similar DNA sequences [5]. For instance, in one study, researchers engineered TALENs with ncRVDs to distinguish between the highly similar HBB and HBD genes (94% identity), successfully reducing off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity [5].

ZFNs also exhibit high specificity due to their relatively long recognition sites (18-36 bp for a ZFN pair) and the FokI dimerization requirement [1] [3]. However, ZFN design can be complicated by context-dependent effects between adjacent zinc fingers, which can affect DNA-binding specificity [1]. The potential for off-target effects exists if ZFNs bind and cleave at sites with similar sequences, though proper design minimizes this risk.

CRISPR-Cas9 systems have raised more concerns about off-target effects because the gRNA can tolerate mismatches, particularly in the 5' region distal to the PAM sequence [3] [2]. However, the off-target effects of CRISPR are generally considered more predictable than those of ZFNs and TALENs because they primarily depend on sequence homology [2]. Numerous strategies have been developed to improve CRISPR specificity, including the use of high-fidelity Cas9 variants, truncated gRNAs with enhanced specificity, and dual nickase systems that require two adjacent gRNAs for double-strand break formation [2] [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Efficiency and Practical Parameters

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and practical characteristics of the three genome editing technologies, based on comparative experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major Genome Editing Technologies

| Parameter | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Mechanism | Protein-DNA interaction [1] | Protein-DNA interaction [1] | RNA-DNA hybridization [2] |

| Typical Target Size | 18-36 bp per ZFN pair [2] | 30-40 bp per TALEN pair [2] | 22 bp [2] |

| Editing Efficiency | 0%-12% (low) [2] | 0%-76% (moderate) [2] | 0%-81% (high) [2] |

| Ease of Design | Difficult, requires protein engineering for each target [3] [2] | Difficult, requires protein engineering for each target [3] [2] | Easy, only requires changing gRNA sequence [3] [2] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Less feasible [2] | Less feasible [2] | Highly feasible [2] |

| Off-Target Prediction | Less predictable [2] | Less predictable [2] | Highly predictable [2] |

| Construction Cost & Time | High cost, time-consuming [3] | High cost, time-consuming [3] | Low cost, rapid [3] |

| Common Delivery Methods | AAV, viral vectors [4] [2] | AAV, viral vectors [2] | AAV, lentivirus, non-viral methods [7] [2] |

Experimental Approaches for Assessing Specificity

Methodologies for Evaluating TALEN Specificity

The high specificity of TALENs has been systematically validated through rigorous experimental approaches. One comprehensive study employed a library-based high-throughput screen of TALENs containing non-conventional RVDs (ncRVDs) [5]. The experimental workflow involved:

- Library Construction: Creating a library of degenerate RVDs randomized at positions 12 and 13 using short overlap PCR with NNK codon degeneracy, then incorporating these RVDs into TALEN arrays via solid-phase assembly [5].

- Specificity Profiling: Screening approximately 18,000 TALEN-target combinations in a yeast-based assay system to characterize the cleavage activity and specificity of each ncRVD variant [5].

- Hierarchical Clustering: Analyzing cleavage profiles to identify clusters of RVDs with similar specificity patterns, revealing that the identity of amino acids at positions 12 and 13 has a more pronounced impact on nuclease activity and specificity than the RVD's position in the array [5].

- Validation in Mammalian Cells: Testing selected TALENs with optimized ncRVDs in mammalian cells to demonstrate their ability to discriminate between highly similar target sequences, such as the HBB and HBD genes (94% identity) [5].

This systematic approach identified ncRVDs with enhanced discriminatory power, enabling the design of TALENs that minimize off-target effects while maintaining robust on-target activity—a crucial consideration for therapeutic applications [5].

CRISPR-Cas9 Specificity Assessment

Multiple methods have been developed to evaluate and improve CRISPR-Cas9 specificity:

- In Silico Prediction: Computational tools predict potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity to the intended target, particularly in the seed region near the PAM sequence [2].

- Genome-Wide Assays: Techniques such as CIRCLE-seq, GUIDE-seq, and BLESS directly capture off-target cleavage events across the entire genome, providing experimental validation of specificity [2].

- High-Fidelity Variants: Engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced off-target activity, such as eSpCas9 and SpCas9-HF1, have been developed through rational design to minimize non-specific interactions with DNA [2] [6].

- Dual Nickase Systems: Using two Cas9 nickases with paired gRNAs to create staggered cuts rather than double-strand breaks significantly enhances specificity, as off-target sites are unlikely to be cleaved by both nickases simultaneously [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential reagents and tools used in genome editing research, providing researchers with a practical resource for experimental planning.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Editing Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Technology |

|---|---|---|

| CompoZr ZFN Platform | Pre-designed, validated ZFNs for specific genomic targets [1] | ZFN |

| TALE Repeat Kits | Molecular cloning kits for assembling custom TALE arrays (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) [1] | TALEN |

| Cas9 Expression Vectors | Plasmids encoding Cas9 nuclease with various promoters for different cell types [2] | CRISPR |

| Guide RNA Cloning Systems | Backbone vectors for rapid insertion of target-specific guide RNA sequences [2] | CRISPR |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced off-target effects (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) [2] [6] | CRISPR |

| AAV Delivery Vectors | Adeno-associated virus serotypes optimized for efficient delivery of editing components [7] [4] | All |

| Off-Target Assessment Kits | Commercial kits for genome-wide identification of off-target sites (e.g., GUIDE-seq) [2] | All |

The fundamental distinction between RNA-guided and protein-DNA interaction mechanisms underlies the practical differences in specificity, efficiency, and ease-of-use among major genome editing technologies. TALENs offer high specificity due to their long recognition sequences and tunable RVDs, making them suitable for applications where precision is paramount. ZFNs, while historically important, present greater design challenges. CRISPR-Cas systems provide unprecedented flexibility and ease of design, with continuously improving specificity through engineered variants and optimized protocols.

The choice between these systems depends on the specific research requirements: TALENs for high-precision applications with minimal off-target effects, and CRISPR for multiplexed experiments and projects requiring rapid implementation. As these technologies continue to evolve, particularly with the emergence of base editing and prime editing systems, the landscape of precision genome editing will continue to offer increasingly sophisticated solutions for research and therapeutic development.

The advent of programmable nucleases has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling precise modifications to DNA sequences within living cells. Among the most significant technologies in this domain are Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Each platform employs a distinct structural approach to achieve DNA recognition and cleavage. ZFNs and TALENs rely on engineered protein domains to directly interact with DNA sequences, while CRISPR-Cas9 utilizes a guide RNA (gRNA) molecule to direct a nuclease enzyme to a specific genomic locus. Understanding the molecular architecture of these systems—specifically the composition of zinc finger arrays, TALE repeats, and gRNA—is critical for selecting the appropriate tool for specific research or therapeutic applications. These architectures directly influence key performance parameters including specificity, efficiency, ease of design, and potential for off-target effects [8] [9]. This guide provides a structural comparison of these three systems, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Architecture and Design

Zinc Finger Arrays (ZFNs)

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) are synthetic proteins created by fusing a custom-designed zinc finger array to the catalytic domain of the FokI restriction enzyme. The DNA-binding domain consists of multiple zinc finger motifs, each comprising approximately 30 amino acids folded around a zinc ion. A fundamental aspect of their architecture is that each individual zinc finger motif recognizes and binds to a specific 3-base pair (bp) DNA triplet [10] [9]. To target a unique genomic sequence, researchers engineer an array of multiple fingers (typically 3 to 6) in tandem, creating a protein domain that recognizes a contiguous 9 to 18 bp sequence. Since FokI requires dimerization to become active, a pair of ZFNs must be designed to bind opposite strands of the DNA, flanking the intended cleavage site. The cleavage event occurs in the spacer region between the two binding sites [9].

The primary challenge with ZFN technology lies in its complex design process. Achieving high-affinity and specific binding often requires extensive optimization, as the DNA-binding specificity of individual zinc fingers can be influenced by context—neighboring fingers can affect each other's binding preferences. This context-dependent specificity makes the rational design of ZFNs challenging and time-consuming, often requiring specialized expertise and sophisticated screening methods to develop effective nucleases [10] [11] [9].

TALE Repeats (TALENs)

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) are also fusion proteins, combining a DNA-binding domain derived from TAL effectors (proteins from plant pathogens) with the FokI nuclease domain. The DNA-binding domain is composed of highly conserved TALE repeats, each typically 33-35 amino acids in length [9]. A key breakthrough that made TALENs a transformative technology was the discovery of a simple, modular code for DNA recognition: within each repeat, two variable amino acids at positions 12 and 13, known as the Repeat-Variable Diresidue (RVD), determine nucleotide specificity [10] [9].

Common RVDs and their recognized nucleotides include:

- NI for Adenine (A)

- NG for Thymine (T)

- HD for Cytosine (C)

- NN for Guanine (G) or Adenine (A) [10] [9]

This one-to-one correspondence between RVDs and DNA bases makes TALEN design highly predictable and straightforward compared to ZFNs. Researchers can essentially string together a series of TALE repeats in an order that mirrors the target DNA sequence. Like ZFNs, TALENs function as pairs, with two TALEN proteins binding to opposite DNA strands and the FokI domains dimerizing to create a double-strand break in the intervening spacer region. While the design is more modular, a practical limitation is the large size of the TALEN coding sequence and the repetitive nature of the TALE repeats, which can complicate viral packaging and introduce challenges in cloning [10] [11].

Guide RNA (gRNA) in CRISPR-Cas9

The CRISPR-Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated protein 9) system functions through a fundamentally different mechanism. Its specificity is conferred not by a protein domain, but by a short guide RNA (gRNA) [8]. The gRNA is a synthetic chimera composed of a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) derivative, which contains a ~20 nucleotide sequence complementary to the target DNA, and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a scaffold for binding the Cas9 nuclease [10]. The gRNA directs the Cas9 protein to the target site through Watson-Crick base pairing between its spacer sequence and the genomic DNA.

A critical requirement for Cas9 recognition and cleavage is the presence of a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence immediately downstream of the target site. The most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence, where "N" can be any nucleotide [10]. Upon binding to a target sequence that is complementary to the gRNA and adjacent to a valid PAM, the Cas9 protein undergoes a conformational change that activates its two nuclease domains (HNH and RuvC), generating a blunt-ended double-strand break [8] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental architectural differences and the common double-strand break repair pathways shared by these technologies.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Direct comparative studies provide the most valuable insights for tool selection. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9, drawing from multiple sources, including a seminal parallel comparison using the GUIDE-seq method for detecting off-target effects [12] [13] [8].

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 (SpCas9) | TALENs | ZFNs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Molecule | Guide RNA (gRNA) | TALE Protein Repeats | Zinc Finger Protein Array |

| Recognition Code | RNA-DNA base pairing (~20 nt) | 1 RVD : 1 DNA base | 1 finger : ~3 DNA bases |

| Specificity (Off-Targets) | Variable; can be high with optimized systems [13] | Generally high [13] [11] | Can be significant; design-dependent [13] |

| Efficiency (Knockout) | High [12] [8] | Moderate to High [8] [11] | Moderate [8] |

| Ease of Design & Use | Very high (designing a gRNA is simple) [8] [10] | Moderate (requires protein engineering) [8] [10] | Low (complex, context-dependent design) [8] [10] |

| Time to Develop Reagents | Days [8] | Days to weeks [10] | Months [10] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs easily designed) [8] | Low (difficult to engineer multiple proteins) [8] | Low (difficult to engineer multiple proteins) [8] |

| Typical Cost | Low [8] [10] | High [8] [10] | Very High [8] [10] |

| Key Limitation | PAM requirement, off-target effects [8] [10] | Large size, repetitive sequence, delivery challenges [10] [11] | Difficult, time-consuming design; potential cytotoxicity [10] [11] |

A critical 2021 study provided a direct, parallel comparison of the three nuclease platforms using the GUIDE-seq method to genome-widely profile off-target effects in the context of human papillomavirus (HPV) gene therapy [13]. The results were striking:

- In the HPV URR region, SpCas9 had 0 off-target sites detected, compared to 1 for TALENs and 287 for one ZFN pair [13].

- In the E6 region, SpCas9 had 0 off-targets, while TALENs had 7 [13].

- In the E7 region, SpCas9 had 4 off-targets, which was still significantly fewer than the 36 detected for TALENs [13].

This study concluded that for their specific application, SpCas9 was both more efficient and specific than ZFNs and TALENs [13]. It is important to note that CRISPR specificity continues to improve with the development of high-fidelity Cas9 variants.

Beyond specificity, survey data from the drug discovery sector reveals practical workflow differences. Generating a CRISPR knockout cell line takes a median of 3 months, while a knock-in takes 6 months. Furthermore, researchers often must repeat the entire CRISPR workflow a median of 3 times before achieving success, highlighting that even the most user-friendly system involves a tedious and time-consuming process [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of comparative studies and the validation of nuclease performance, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for two key assays used in the cited research.

GUIDE-seq for Genome-Wide Off-Target Detection

The GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by sequencing) method is a powerful and sensitive technique for detecting off-target nuclease activity without prior knowledge of potential sites [13].

Principle: A short, double-stranded oligonucleotide tag is incorporated into double-strand breaks (DSBs) generated by the nuclease in living cells. These tagged sites are then enriched and identified via next-generation sequencing.

Key Reagents:

- Oligonucleotide Tag: A short, blunt-ended, double-stranded DNA oligo with phosphorothioate linkages on the ends to resist exonuclease digestion.

- Transfection Reagent: For delivering the nuclease constructs and the oligonucleotide tag into the target cells.

- PCR Primers: Specific to the oligonucleotide tag for amplification of integrated sites.

- Next-Generation Sequencing Platform.

Procedure:

- Co-transfection: Co-deliver the nuclease expression plasmid (or ribonucleoprotein complex for CRISPR) and the GUIDE-seq oligonucleotide tag into the target cells.

- Incubation: Allow cells to grow for 48-72 hours to permit nuclease activity and tag integration.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells and extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA.

- Tag-Specific PCR: Shear the genomic DNA and perform PCR using a biotinylated primer specific to the integrated oligo tag.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Purify the PCR amplicons, prepare a sequencing library, and sequence on an NGS platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map the sequencing reads back to the reference genome to identify all genomic locations where the tag was integrated, which correspond to nuclease-induced DSBs. Compare these sites to the intended on-target sequence to catalog off-target events [13].

Cell Viability and Editing Efficiency Assay

This protocol assesses the functional efficiency and cytotoxicity of nucleases, which is crucial for therapeutic applications.

Principle: The rate of targeted mutagenesis is measured at the on-target site, while cell survival and health are monitored to evaluate the toxicity associated with nuclease expression.

Key Reagents:

- Nuclease Expression Vectors: Plasmids or mRNA encoding ZFNs, TALENs, or CRISPR-Cas9/gRNA.

- Control Vectors: Inactive nuclease controls (e.g., catalytically dead Cas9 for CRISPR).

- Cell Culture Reagents.

- Genomic DNA Extraction Kit.

- T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor Nuclease: For detecting mismatches in heteroduplex DNA caused by NHEJ repair.

- PCR Reagents and Primers flanking the target site.

- Cell Viability Assay Kit (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo).

Procedure:

- Cell Transfection: Introduce nuclease constructs into the chosen cell model (e.g., immortalized cell lines, primary cells). Include controls transfected with inactive nucleases and non-transfected cells.

- Viability Measurement: At 72-96 hours post-transfection, assay cell viability using a method like ATP quantification (CellTiter-Glo). Normalize viability to control treatments to determine nuclease-associated toxicity [12] [11].

- Harvest Genomic DNA: Extract genomic DNA from a portion of the transfected cell population.

- Amplify Target Locus: Perform PCR to amplify the genomic region surrounding the nuclease target site.

- Detect Indel Mutations:

- T7E1/Surveyor Assay: Denature and reanneal the PCR products to form heteroduplexes. Digestion with the mismatch-specific nuclease will cleave the DNA if indels are present. Analyze the cleavage products by gel electrophoresis. The ratio of cleaved to uncleaved products allows for estimation of editing efficiency [9].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of indels and correlate this with cell viability data to determine the therapeutic index of the nuclease.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful gene editing experiments require a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions for working with these nuclease platforms.

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Expression Plasmid | A vector for expressing the custom ~20 nt gRNA within cells; the core of CRISPR experiment design. |

| Cas9 Expression Plasmid or mRNA | Delivers the Cas9 nuclease; can be co-delivered with gRNA plasmid or used as a pre-complexed Ribonucleoprotein (RNP). |

| TALEN Expression Kit | Modular kits (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) containing TALE repeat modules for efficient construction of custom TALEN pairs. |

| ZFN Expression Vector | Plasmids for expressing the pairs of engineered zinc finger proteins fused to FokI nuclease. |

| GUIDE-seq Oligo Duplex | The double-stranded oligonucleotide tag used for genome-wide, unbiased identification of off-target cleavage sites. |

| T7 Endonuclease I / Surveyor Nuclease | Enzymes used for the rapid detection and quantification of indel mutations at the target site. |

| HDR Donor Template | Single-stranded oligonucleotide (ssODN) or double-stranded DNA vector containing the desired edit flanked by homology arms, used for precise knock-in via HDR. |

| Cell Line-Specific Transfection Reagent | Chemical or lipid-based reagents for efficient delivery of nuclease constructs (DNA, RNA, or RNP) into target cells. |

| NGS-Based Off-Target Analysis Service | Commercial services that use methods like GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq to provide a comprehensive report of nuclease off-target activity. |

The structural deep dive into gRNA, TALE repeats, and zinc finger arrays reveals a clear trade-off between simplicity and precision. CRISPR-Cas9, with its RNA-guided architecture, offers an unparalleled combination of ease of design, high efficiency, and multiplexing capability, making it the dominant tool for most high-throughput and research applications [12] [8]. However, its specificity is contingent on gRNA design and can be prone to off-target effects, though high-fidelity variants are mitigating this issue [13] [8].

TALENs, with their modular protein-DNA code, provide high specificity and are effective in targeting complex regions, making them valuable for therapeutic applications where minimizing off-targets is paramount [13] [11]. Their main drawbacks are the larger size and more labor-intensive protein engineering process.

ZFNs, as the pioneering technology, demonstrated the feasibility of programmable gene editing but are now largely superseded due to their complex, context-dependent design process and higher potential for cytotoxicity and off-target effects [13] [10] [11].

The choice among these platforms is not one-size-fits-all. For rapid screening and multiplexed experiments, CRISPR is often the optimal choice. For clinical applications requiring the highest possible specificity and where delivery constraints can be overcome, TALENs remain a powerful alternative. The continued advancement of all three platforms, including the development of base editors and prime editors, ensures that the gene editing toolkit will continue to expand, offering researchers and clinicians increasingly sophisticated instruments for precise genetic manipulation.

The Critical Role of PAM Sequences in CRISPR and Their Impact on Targetable Sites

The advent of programmable genome editing technologies has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development. Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR-Cas9 system represent three generations of genome editing tools that enable precise modifications to DNA sequences [14]. These technologies function by creating targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA, which are subsequently repaired by the cell's endogenous repair mechanisms—either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) [15] [16]. While all three systems achieve the same fundamental goal of targeted genome modification, they differ dramatically in their molecular architectures, recognition mechanisms, and practical implementation. The CRISPR-Cas9 system, in particular, has gained widespread adoption due to its simplicity and versatility, but its targeting capabilities are constrained by a unique requirement: the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence [17] [18]. This PAM requirement represents a critical differentiator between CRISPR and earlier technologies, with profound implications for targetable sites in the genome, experimental design, and therapeutic applications.

The comparative analysis of these editing technologies extends beyond mere mechanism to encompass critical performance metrics including specificity, efficiency, and ease of design. TALENs employ a pair of customizable DNA-binding proteins derived from plant pathogens fused to the FokI nuclease domain, with each DNA-binding module recognizing a single nucleotide [19] [16]. ZFNs similarly utilize FokI nuclease but rely on zinc finger protein arrays that typically recognize triplets of nucleotides [19] [14]. In contrast, the CRISPR-Cas9 system depends on a complex between the Cas9 nuclease and a short guide RNA (sgRNA) that hybridizes with the target DNA through Watson-Crick base pairing [17] [14]. This fundamental difference in recognition mechanism—protein-DNA for ZFNs and TALENs versus RNA-DNA for CRISPR—underlies their distinct strengths and limitations, particularly regarding PAM constraints and targeting flexibility.

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): A Critical CRISPR-Specific Requirement

Biological Function and Definition

The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs in length) that immediately follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR-Cas system [17] [18]. This motif serves as an essential recognition element that enables Cas nucleases to distinguish between self and non-self DNA, thereby preventing autoimmunity in bacterial CRISPR systems [17] [20]. In nature, when bacteria survive viral infection, they incorporate fragments of viral DNA (protospacers) into their CRISPR arrays as spacers [17]. During subsequent infections, the CRISPR system must be able to recognize and cleave the viral DNA (which contains the PAM) while avoiding the bacterial genome (where the spacer sequences lack PAMs) [17] [18]. The PAM sequence is thus not part of the guide RNA target but must be present adjacent to the target site in the DNA for successful recognition and cleavage by Cas nuclease [17].

From a structural perspective, PAM recognition occurs through specific interactions between the PAM DNA and particular domains of the Cas protein. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM is recognized by a arginine-rich motif in the C-terminal domain of the protein [20]. This interaction triggers conformational changes that facilitate DNA unwinding and subsequent RNA-DNA hybridization [20]. The PAM sequence therefore serves as an essential binding signal that must be identified before Cas9 can proceed with checking for complementarity between the guide RNA and target DNA [17]. This sequential recognition mechanism—PAM identification followed by target verification—ensures both efficiency and specificity in DNA targeting.

PAM Sequences Across Different Cas Nucleases

Different Cas nucleases recognize distinct PAM sequences, which significantly influences their targeting ranges and applications. The canonical SpCas9 requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM (where "N" can be any nucleotide base) immediately following the target sequence [17] [18]. However, the natural diversity of CRISPR systems and recent protein engineering efforts have yielded Cas variants with altered PAM specificities, substantially expanding the targetable genome [17] [21].

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Various CRISPR Nucleases

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism/Source | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | Canonical Cas9; most widely used [17] |

| SpCas9-NG | Engineered SpCas9 | NG | Expanded targeting range [21] |

| SpRY | Engineered SpCas9 | NRN > NYN | Near-PAMless variant [21] |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV | Creates staggered ends [17] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN | Smaller size for viral delivery [17] |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | Longer PAM; high specificity [17] |

| Cas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | Thermostable variant [17] |

| Cas14 | Uncultivated archaea | T-rich (e.g., TTTA) | Targets single-stranded DNA [17] |

The diversity of PAM requirements across different Cas nucleases provides researchers with a toolbox of targeting options. For example, Cas12a (Cpf1) recognizes T-rich PAM sequences (TTTV, where V is A, C, or G) and creates staggered DNA ends rather than blunt cuts, which can be advantageous for certain applications [17]. Smaller Cas variants such as SaCas9 offer more compact coding sequences suitable for viral vector delivery while maintaining robust activity [17]. Recent engineering approaches have dramatically expanded PAM compatibilities, with variants like SpRY recognizing virtually all possible PAM sequences with efficiencies of NRN > NYN (where R is A/G and Y is C/T) [21]. This ongoing expansion of PAM diversity continues to broaden the targeting scope of CRISPR technologies.

Comparative Analysis of Genome Editing Technologies

Mechanism of Target Recognition

The three major genome editing technologies employ fundamentally different mechanisms for DNA recognition, which directly impacts their targeting flexibility, specificity, and ease of design:

CRISPR-Cas9: The CRISPR-Cas9 system relies on RNA-DNA complementarity for target recognition. A single guide RNA (sgRNA) of approximately 20 nucleotides directs the Cas9 nuclease to complementary genomic sequences [14]. Critical to this recognition is the requirement for a specific PAM sequence adjacent to the target site [17]. The Cas9 protein first scans DNA for the appropriate PAM sequence; upon identifying a PAM, it unwinds the adjacent DNA to allow hybridization with the guide RNA [20]. If sufficient complementarity exists, particularly in the "seed" region proximal to the PAM, Cas9 introduces a double-strand break 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM [17].

TALENs: Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases utilize a pair of customizable protein-DNA interactions for targeting [16]. Each TALEN consists of a DNA-binding domain derived from plant pathogenic bacteria fused to the FokI nuclease domain [19]. The DNA-binding domain comprises tandem repeats of 33-35 amino acids, with each repeat recognizing a single nucleotide through two hypervariable residues (Repeat Variable Diresidues or RVDs) [19] [16]. The RVD code follows a predictable pattern: NI recognizes adenine, HD recognizes cytosine, NG recognizes thymine, and NN recognizes guanine [16]. TALENs function as pairs binding to opposite DNA strands with a spacer sequence between them, enabling FokI dimerization and DNA cleavage [16].

ZFNs: Zinc Finger Nucleases also operate as pairs utilizing protein-DNA interactions but employ a different recognition code. Each zinc finger domain recognizes approximately 3 base pairs of DNA [19] [14]. Arrays of multiple zinc fingers (typically 3-6) are fused to the FokI nuclease domain to create target specificity [19]. Like TALENs, ZFNs must bind as pairs to opposite DNA strands with a spacer between them to facilitate FokI dimerization and DNA cleavage [14]. However, zinc finger arrays exhibit context-dependent effects where the recognition specificity of individual fingers can be influenced by neighboring fingers, making ZFN design more challenging [19].

Figure 1: Comparative mechanisms of target recognition by CRISPR, TALENs, and ZFNs

Targeting Flexibility and Limitations

The PAM requirement of CRISPR systems imposes a significant constraint on targeting flexibility compared to TALENs and ZFNs. While CRISPR guide RNAs can be easily designed to target virtually any sequence preceding an appropriate PAM, the absolute dependence on this short motif means that certain genomic regions may be inaccessible with standard Cas variants [17] [18]. For example, the canonical SpCas9 requiring 5'-NGG-3' PAM occurs approximately every 8-12 base pairs in random DNA sequence, but in practice, the distribution is non-random and some genomic regions may lack suitable PAMs for targeting specific nucleotides of interest [17].

In contrast, TALENs and ZFNs offer greater theoretical targeting flexibility since they do not operate under PAM constraints [16]. TALENs can potentially target any sequence with appropriate design, as the recognition is based on a straightforward one-to-one protein-DNA binding code [19]. Similarly, ZFNs can be designed to recognize a wide range of sequences, though the context-dependency of zinc finger arrays makes some targets more challenging than others [19]. However, both TALENs and ZFNs require designing and delivering pairs of proteins for each target, which complicates experimental design and implementation, particularly for multiplexed applications [16].

Table 2: Targeting Flexibility Comparison of Genome Editing Technologies

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs | ZFNs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition Mechanism | RNA-DNA hybridization | Protein-DNA (1bp/RVD) | Protein-DNA (3bp/zinc finger) |

| Sequence Constraint | Requires PAM sequence (e.g., NGG for SpCas9) | No PAM requirement | No PAM requirement |

| Targeting Density | Limited by PAM frequency | Potentially any sequence | Limited by zinc finger availability |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs) | Low (pairs of large proteins) | Low (pairs of proteins) |

| Ease of Design | Simple (design sgRNA sequence) | Moderate (design TALE arrays) | Complex (context-dependent zinc fingers) |

| Development Time | Days | Days to weeks | Weeks to months [10] |

Recent advances in Cas engineering have substantially addressed CRISPR's PAM limitation. Through directed evolution and structure-guided engineering, researchers have developed Cas9 variants with altered PAM specificities [21]. Notable examples include xCas9 and SpCas9-NG variants that recognize NG PAMs, and SpRY that approaches PAM-less behavior [21]. A 2025 study published in Nature combined high-throughput protein engineering with machine learning to generate nearly 1,000 engineered SpCas9 enzymes with diverse PAM requirements, enabling "bespoke editors" for specific targets [21]. This evolving landscape continues to narrow the targeting flexibility gap between CRISPR and earlier technologies.

Experimental Evidence: Efficiency and Specificity Comparisons

Editing Efficiency and Pattern Analysis

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in editing efficiencies between CRISPR-Cas9 and TALENs. In a 2016 study comparing these technologies for editing an integrated EGFP gene in HEK293FT cells, researchers found that paired Cas9 nucleases induced targeted genomic deletion more efficiently and precisely than two TALEN pairs [15]. However, when concurrently supplied with a plasmid template spanning two double-strand breaks within EGFP, TALENs stimulated homology-directed repair more efficiently than CRISPR/Cas9 and caused fewer targeted genomic deletions [15]. This suggests that the choice of genome editing tool should be determined by the desired genomic outcome, with CRISPR potentially superior for gene knockouts through NHEJ, and TALENs possibly more efficient for precise gene insertion through HDR.

A 2018 study specifically compared editing patterns and efficiencies at the beginning of the CCR5 gene, an important therapeutic target for HIV treatment [22]. The results demonstrated that CRISPR-Cas9 mediated the sorting of cells that contained 4.8 times more gene editing than TALEN-transfected cells [22]. This substantial difference in editing efficiency highlights one of CRISPR's significant advantages for therapeutic applications where high editing rates are critical. The study employed detailed DNA sequencing to analyze editing patterns, revealing that both technologies produced diverse indels at the target site, but with different distribution profiles [22].

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Efficiencies from Experimental Studies

| Study | Target | Cell Type | Editing Efficiency (CRISPR) | Editing Efficiency (TALEN) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| He et al. (2016) [15] | EGFP | HEK293FT | High (paired nucleases) | Moderate | CRISPR more efficient for genomic deletions |

| Wang et al. (2018) [22] | CCR5 | Human cells | 4.8x higher | Baseline | CRISPR significantly more efficient |

| GeneCopoeia Comparison [16] | Various | Multiple | >70% indel formation | ~33% indel formation | CRISPR generally higher efficiency |

Off-Target Effects and Specificity

Specificity remains a critical consideration for all genome editing technologies, particularly for therapeutic applications. CRISPR-Cas9 has been reported to tolerate some mismatches between the guide RNA and target DNA, especially in the 5' region distal from the PAM, potentially leading to off-target effects at sites with similar sequences [16]. One study noted that sgRNAs can tolerate up to five mismatches with unintended target sites, though the extent of off-target activity varies significantly between different sgRNAs and cell types [16].

TALENs generally demonstrate higher specificity with fewer off-target effects, attributed to their requirement for longer recognition sequences and the obligate dimerization of FokI nuclease domains [16] [22]. The need for two TALEN proteins to bind in close proximity at the target site significantly reduces the probability of off-target cleavage. Similarly, ZFNs benefit from the FokI dimerization requirement, though their off-target profiles can be more variable due to the challenges in designing highly specific zinc finger arrays [19].

Several strategies have been developed to improve CRISPR specificity, including:

- Truncated sgRNAs (17-18 nucleotides instead of 20) that reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity [16] [22]

- Paired nickases using Cas9 mutants that make single-strand breaks rather than double-strand breaks, requiring two adjacent sgRNAs for cutting [16]

- High-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) with engineered mutations that reduce non-specific interactions with DNA [14]

- RNA-guided FokI nucleases (RFNs) that fuse catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI, reinstating the dimerization requirement for activity [16]

Figure 2: Strategies to address off-target effects in genome editing technologies

Experimental Protocols for Technology Comparison

Side-by-Side Editing Assessment Protocol

To directly compare the editing efficiencies of CRISPR-Cas9 and TALENs, researchers can implement the following experimental protocol adapted from published comparative studies [15] [22]:

1. Target Selection and Editor Design:

- Select a target gene of interest with known sequence and function (e.g., EGFP or CCR5 as in published studies)

- For CRISPR-Cas9: Design sgRNAs targeting the region of interest using established tools, ensuring each target is followed by an appropriate PAM (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9). Cloning involves synthesizing oligonucleotides corresponding to the sgRNA sequence and inserting them into an appropriate expression plasmid containing the Cas9 coding sequence [15] [22]

- For TALENs: Design TALEN pairs targeting the same region using online tools such as ZiFiT Targeter. Each TALEN should target 15-20 bp with a spacer of 14-20 bp between them. Assembly typically employs Golden Gate cloning with modular TALE repeat arrays [15]

2. Vector Construction:

- CRISPR-Cas9: Clone sgRNA sequences into a Cas9 expression plasmid (e.g., Addgene #41815). Many CRISPR plasmids incorporate fluorescent markers (e.g., GFP) or antibiotic resistance genes for selection [22]

- TALENs: Assemble TALEN pairs using established protocols such as the Golden Gate method. Co-transfect with a reporter plasmid that expresses RFP upon transfection and GFP only upon successful TALEN cleavage and repair-mediated frame correction [22]

3. Cell Transfection and Selection:

- Culture appropriate cell lines (e.g., HEK293FT) and seed in 24-well plates at 1.5×10^5 cells/well

- Transfect using recommended reagents (e.g., X-tremeGENE HP):

- For CRISPR: 0.3 μg Cas9 plasmid + 0.1 μg of each sgRNA plasmid (for paired nucleases)

- For TALENs: 0.1 μg of each TALEN plasmid + 0.1 μg reporter plasmid [15]

- Include untransfected controls and single-transfected controls where appropriate

4. Analysis of Editing Efficiency:

- Harvest cells 3 days post-transfection for initial assessment of editing

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit)

- Amplify target region by PCR and assess editing using:

5. Functional Assessment:

- For reporter genes like EGFP, use flow cytometry to quantify functional knockout rates 7 days post-transfection [15]

- For endogenous genes, perform functional assays appropriate to the target (e.g., antibody staining for surface receptors like CCR5) [22]

Assessment of Off-Target Effects

Evaluating the specificity of editing technologies is crucial for applications requiring high precision:

1. In Silico Prediction of Off-Target Sites:

- For CRISPR: Identify potential off-target sites using tools that search for genomic sequences with similarity to the sgRNA target, allowing for mismatches, especially in the 5' region

- For TALENs: Identify sites with similarity to the TALEN binding sites, considering the degeneracy of RVD codes

2. Experimental Detection Methods:

- GUIDE-seq: Genome-wide, unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing uses integration of oligonucleotides into DSB sites to identify both on-target and off-target cleavage sites [18]

- * targeted sequencing*: Deep sequencing of predicted off-target sites to quantify editing frequencies

- Whole-genome sequencing for comprehensive identification of off-target effects in clonal populations

Successful implementation of genome editing technologies requires specific reagent systems and tools. The following table outlines key solutions for researchers embarking on comparative studies of CRISPR and TALEN technologies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Editing Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | CRISPR-Specific Notes | TALEN-Specific Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Plasmid | Expresses Cas9 nuclease | Codon-optimized versions available for different species; high-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects | Not applicable |

| TALEN Expression Vectors | Expresses TALEN proteins | Not applicable | Typically require pair of plasmids for left and right TALENs |

| sgRNA Cloning Vector | Template for sgRNA expression | U6 promoter drives expression; requires insertion of 20nt target sequence | Not applicable |

| Reporter Plasmid | Assesses editing efficiency | Often incorporated into Cas9 vector (e.g., T2A-GFP) | Separate plasmid expressing RFP/GFP upon successful editing [22] |

| Delivery Reagents | Introduces editing components into cells | Lipid-based transfection, electroporation, or viral delivery | Similar delivery methods, but larger payload size for TALENs |

| Target Validation Tools | Confirms editing at target site | Surveyor/T7E1 assay, tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE), next-generation sequencing | Same validation methods applicable |

| Off-Target Assessment | Identifies unintended edits | GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq, targeted sequencing | Similar approaches but generally fewer off-target concerns |

The selection of appropriate reagents significantly influences editing outcomes. For CRISPR systems, the choice of Cas9 variant (wild-type, high-fidelity, nickase) determines both targeting range and specificity [14]. For TALENs, the design of RVD arrays and spacer length between binding sites affects activity and specificity [16]. Recent commercial sources provide pre-validated editors for common targets, reducing development time and improving success rates, particularly for researchers new to genome editing.

The critical role of PAM sequences in CRISPR technology represents both a constraint and an opportunity for genome engineering applications. While the PAM requirement limits the theoretical targeting space compared to TALENs and ZFNs, ongoing engineering efforts are rapidly expanding this boundary. The development of PAM-flexible Cas variants through directed evolution and structure-based design continues to increase the targetable genome [21]. A 2025 study demonstrated the power of combining high-throughput protein engineering with machine learning to generate bespoke Cas9 variants with customized PAM specificities, potentially enabling allele-selective editing for therapeutic applications [21].

The choice between CRISPR, TALENs, and ZFNs depends heavily on the specific research or therapeutic context. CRISPR-Cas9 offers unparalleled ease of design, high efficiency, and straightforward multiplexing capabilities, making it ideal for most research applications, particularly gene knockouts [15] [22]. TALENs provide high specificity with minimal off-target effects and no PAM constraints, advantageous for applications requiring precise editing in sensitive genomic contexts [16]. ZFNs, while more challenging to design, offer compact coding sequences and established safety profiles that have enabled their use in clinical trials [19].

Future developments in genome editing will likely focus on expanding targeting scope, improving specificity, and enhancing editing precision. For CRISPR systems, continued engineering of Cas variants with novel PAM specificities will further close the gap in targeting flexibility [21]. The integration of machine learning approaches to predict both on-target efficiency and off-target effects for specific guide RNAs will improve experimental design and outcomes [21]. As these technologies mature, the critical role of PAM sequences in determining targetable sites will continue to evolve, potentially leading to truly PAM-independent editing systems that maintain high specificity while offering complete targeting freedom across the genome.

Inherent FokI Dimerization in TALENs/ZFNs as a Natural Specificity Check

The quest for precision in genome editing has positioned engineered nucleases as powerful tools for research and therapy. Within this landscape, the inherent structural requirement for FokI nuclease dimerization in Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) acts as a critical, built-in mechanism that enhances target specificity. This biological safeguard provides a compelling contrast to the mechanism of the more recent CRISPR-Cas9 system. This guide objectively compares the experimental performance of these platforms, focusing on how the FokI dimerization checkpoint influences editing accuracy, supported by direct experimental data and protocols relevant to drug development professionals.

Mechanism of Action: A Tale of Two Architectures

The core difference in specificity control between platform types lies in their fundamental architecture for DNA recognition and cleavage.

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Mechanism | Protein-DNA interaction [23] | Protein-DNA interaction [23] | RNA-DNA base pairing [23] [8] |

| Recognition Site Length | 9-18 bp [23] [9] | 30-40 bp [23] | 22 bp + PAM sequence [23] |

| Cleavage Domain | FokI nuclease [23] [9] | FokI nuclease [23] | Cas9 nuclease [23] |

| Cleavage Requirement | Obligate FokI Dimerization [23] [9] | Obligate FokI Dimerization [23] | Single Protein with Dual Nuclease Activity [23] |

The following diagram illustrates the critical mechanistic difference: the requirement for two independent binding events in ZFNs and TALENs versus the single-guide system of CRISPR-Cas9.

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying the Specificity Advantage

The theoretical specificity advantage of FokI dimerization has been validated in numerous direct comparative studies. The data below summarize key experimental findings measuring on-target efficiency versus off-target activity.

Table 1: Experimental Data from Direct Nuclease Comparisons. This table synthesizes data from multiple studies quantifying gene targeting efficiency and off-target effects [24] [25] [8].

| Nuclease Platform | Experimental System | Reported On-Target Efficiency | Reported Off-Target Effects | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBB-TALENs | EGFP Reporter Assay in 293T cells [24] | 0.35% HR Frequency [24] | Detected on HBD target (2.4% activity) [24] | Demonstrated that longer recognition sites do not guarantee higher specificity. |

| HBB-ZFNs | EGFP Reporter Assay in 293T cells [24] | ~0.2% HR Frequency [24] | Low level on HBE and HBG sequences [24] | Lower efficiency than more recently developed ZFNs (ZFA pair). |

| HBB-ZFA (Improved ZFN) | EGFP Reporter Assay in 293T cells [24] | ~0.9% HR Frequency [24] | Not detected on related HBD, HBE, HBG sequences [24] | Illustrates that well-designed ZFNs can achieve high specificity. |

| HBB Hybrid (ZFA-L + TALEN1-R) | EGFP Reporter Assay in 293T & human iPS cells [24] | 2.8% HR Frequency (8-fold higher than TALEN1 pair) [24] | Not detected on related HBD, HBE, HBG sequences [24] | Hybrid nuclease showed highest efficiency and no detected off-target activity. |

| Anti-HBV TALENs (2nd Gen Heterodimer) | HBV-transfected Huh7 cells [25] | Similar silencing efficacy to 1st-gen TALENs [25] | Improved specificity in mouse model of HBV replication [25] | Engineering obligate heterodimers maintained efficacy while improving specificity. |

Case Study: Enhanced Specificity with Obligate Heterodimers

A 2021 study on improving TALENs for hepatitis B virus (HBV) therapy directly engineered the FokI domain to create "obligate heterodimeric TALENs" [25]. This approach uses second- and third-generation FokI nuclease domains that are only active when two different TALEN monomers (left and right) dimerize. This prevents cleavage from homodimers (two identical subunits), which could form at off-target sites with similar, but not identical, sequences [25]. The results confirmed that these modified TALENs maintained high activity against viral DNA while demonstrating an improved specificity profile in an in vivo model, showcasing a direct engineering application of the dimerization principle [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Nuclease Specificity

To empower researchers in validating these findings, below is a detailed methodology for a key experiment used to quantify nuclease activity and off-target effects—the EGFP Reporter Assay, adapted from the studies cited [24].

EGFP Reporter Assay for Homologous Recombination (HR) Frequency

Objective: To quantitatively measure the frequency of precise, nuclease-induced gene correction via Homologous recombination in a cell population.

Principle: A cell line harbors a chromosomally integrated, non-functional Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) gene, disrupted by a stop codon and the target DNA sequence of interest. Transfection with nuclease plasmids and a donor DNA template (tGFP) enables HR. Successful correction restores a functional EGFP gene, and cells expressing EGFP are quantified via flow cytometry [24].

Materials & Reagents:

- Stable Reporter Cell Line: e.g., HEK293T or other relevant cell line with integrated, disrupted EGFP gene containing the target site.

- Nuclease Expression Vectors: Plasmids expressing the left and right monomers of the TALEN or ZFN pair, or a plasmid expressing Cas9 and the specific sgRNA.

- Donor DNA Template: A non-expressing "tGFP" donor DNA plasmid for HR, containing the corrected EGFP sequence with the target site removed/mutated.

- Transfection Reagent: e.g., Lipofectamine 3000.

- Flow Cytometer: For detecting and quantifying EGFP-positive cells.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed the stable reporter cells in a multi-well plate (e.g., 6-well) at 50% confluency one day before transfection.

- Transfection: Co-transfect the cells with:

- 1 µg of each nuclease monomer plasmid (for ZFNs/TALENs) or 2 µg of CRISPR-Cas9/sgRNA plasmid.

- 300 ng of the pCH-9/3091 (or similar) target plasmid if required.

- 200 ng of the tGFP donor DNA template.

- 200 ng of a transfection control plasmid (e.g., pCI-neo eGFP).

- Use a mock transfection control (e.g., pUC118 plasmid) in place of nuclease plasmids.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Analysis:

- Visualize transfection efficiency by fluorescence microscopy using the control GFP.

- Harvest cells and resuspend in buffer for flow cytometry.

- Analyze at least 100,000 events per sample to detect EGFP-positive cells.

- Calculate HR Frequency: (Number of EGFP-positive cells / Total number of cells analyzed) × 100%.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Nuclease Studies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Genome Editing Experiments. This table catalogs essential materials used in the featured studies and their critical functions in nuclease research [24] [25].

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TALEN/ZFN Expression Vectors (pVAX, etc.) | Plasmid backbones (e.g., with CMV promoter) for expressing nuclease monomers in mammalian cells [25]. | Delivery of TALEN or ZFN pairs into target cells for gene editing [24]. |

| FokI Nuclease Domain (Wild-type & Obligate Heterodimer Mutants) | The catalytic domain that cleaves DNA; engineered variants require two different monomers to form an active complex [25] [9]. | Enhancing specificity by preventing homodimer formation and off-target cleavage [25]. |

| EGFP Reporter Cell Line | Engineered cell line with a disrupted EGFP gene that can be restored via nuclease-driven HR [24]. | Quantitative measurement of homologous recombination efficiency and functional nuclease activity [24]. |

| Donor DNA Template (ssODN or dsDNA) | A homologous repair template containing the desired genetic modification flanked by homology arms [9]. | Enabling precise gene knock-in or correction via the HDR pathway [24]. |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | A common liposomal transfection reagent for delivering nucleic acids into cultured cells. | Transient transfection of nuclease plasmids and donor DNA into adherent cell lines [25]. |

| Surveyor Nuclease Assay (or T7E1 Assay) | A mismatch-specific endonuclease used to detect nuclease-induced indel mutations at the target site. | Validation of on-target editing efficiency and initial screening for potential off-target sites [25]. |

The inherent need for FokI dimerization in ZFNs and TALENs provides a fundamental, protein-based checkpoint that is absent in the standard single-guide RNA-driven CRISPR-Cas9 system. Experimental data consistently demonstrates that this architecture can result in lower off-target effects, a critical consideration for therapeutic applications. While CRISPR offers unparalleled ease of use and flexibility, the continued development and application of ZFNs and TALENs—especially with advanced FokI engineering—remain vital for projects where the highest possible specificity is non-negotiable. The choice of platform should therefore be guided by a balanced consideration of the project's requirements for ease of design, efficiency, and most importantly, precision.

From Bench to Bedside: Application-Based Selection of Editing Tools

Gene editing has ushered in a transformative era for treating monogenic diseases, moving from theoretical concept to clinical reality. The landscape of programmable nucleases has been historically dominated by zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), which require complex protein engineering for each new DNA target [26]. The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized the field by introducing an RNA-guided system, drastically simplifying design and enabling rapid deployment across diverse applications [8]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, focusing on their therapeutic performance in three landmark diseases: sickle cell disease (SCD), transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT), and hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR). We present structured experimental data, detailed methodologies, and analytical visualizations to illustrate the factors behind CRISPR's emerging dominance in the clinical arena.

Clinical Trial Performance: Quantitative Outcomes Comparison

The most compelling evidence for a therapeutic technology lies in its clinical trial data. The following tables summarize key efficacy and safety outcomes for CRISPR-based therapies across the three target diseases, highlighting the direct clinical results that have propelled CRISPR to the forefront.

Table 1: Efficacy Outcomes from Pivotal CRISPR Clinical Trials

| Disease | Therapy / Trial | Primary Efficacy Endpoint | Result | Patient Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) | Casgevy (ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9) [27] | Freedom from severe vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) for ≥12 consecutive months | 93.5% (29 of 31 evaluable patients) | Patients 12+, with history of recurrent VOCs |

| Transfusion-Dependent Beta Thalassemia (TBT) | Casgevy (ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9) [28] | Freedom from regular blood transfusions for ≥12 consecutive months | 94% (c. 36 of 38 evaluable patients, based on IGI report) | Patients 12+, requiring regular transfusions |

| hATTR Amyloidosis | NTLA-2001 (in vivo CRISPR-Cas9) [28] [29] | Reduction in serum transthyretin (TTR) protein | ~90% reduction sustained at 28 days and through 2-year follow-up | Patients with hATTR with polyneuropathy or cardiomyopathy |

Table 2: Safety and Delivery Profile Comparison

| Therapy | Delivery Method | Common Adverse Events | Notable Risks | Therapeutic Dosing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy (SCD/TBT) [27] | Ex vivo (CD34+ HSPCs) | Low platelets/white blood cells, mouth sores, nausea, febrile neutropenia | Requires myeloablative conditioning | One-time, single-dose infusion |

| NTLA-2001 (hATTR) [28] [30] | In vivo (Systemic LNP) | Mild or moderate infusion-related reactions | No evidence of declining effect over 2 years | Single-dose IV infusion; potential for redosing |

Platform Comparison: CRISPR vs. TALENs vs. ZFNs

While all three nuclease platforms can create targeted double-strand breaks in DNA, their fundamental mechanisms, design processes, and practical implementation differ significantly. The following table provides a structured comparison of their core characteristics, while the diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences that underpin these practical distinctions.

Table 3: Core Technology Comparison of Programmable Nucleases

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs | ZFNs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Mechanism | RNA-guided (gRNA) via Watson-Crick base pairing [26] | Protein-based (TALE repeats) | Protein-based (Zinc finger domains) |

| Nuclease Component | Cas9 (HNH & RuvC domains) [26] | FokI dimer [8] [26] | FokI dimer [8] [26] |

| Design & Development | Simple, rapid gRNA design (days) [8] | Labor-intensive TALE repeat assembly (weeks-months) [8] [26] | Complex zinc finger engineering (weeks-months) [8] [26] |

| Target Specificity | Moderate to high; subject to off-target effects [8] | High; reduced off-target risks [8] | High; proven precision in clinical edits [8] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs simultaneously) [8] | Limited [8] | Very limited [8] |

| Cost Efficiency | Low [8] | High [8] | High [8] |

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of Major Gene-Editing Platforms. CRISPR-Cas9 uses a guide RNA for DNA targeting, while TALENs and ZFNs rely on protein-DNA binding and FokI dimerization for cleavage.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Ex Vivo Editing for SCD: Casgevy (CTX001)

The Casgevy therapy for SCD is a prime example of ex vivo CRISPR editing. The protocol involves isolating a patient's own hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), genetically modifying them outside the body, and then reinfusing them to establish a new, healthy blood system [31] [27].

- HSPC Collection & Isolation: CD34+ HSPCs are collected from the patient via apheresis after mobilization from the bone marrow [31] [27].

- Ex Vivo Editing:

- Myeloablative Conditioning: The patient receives busulfan chemotherapy to clear the bone marrow niche and make space for the engraftment of the edited cells [27].

- Reinfusion & Engraftment: The CRISPR-edited CD34+ cells are infused back into the patient, where they engraft in the bone marrow [27]. The disruption of BCL11A leads to sustained elevation of HbF, which prevents the sickling of red blood cells, thereby ameliorating the disease [31] [27].

In Vivo Editing for hATTR: NTLA-2001

The NTLA-2001 trial for hATTR amyloidosis represents a breakthrough for in vivo CRISPR therapy, where editing occurs directly inside the patient's body [28] [30].

- Vector Design & Formulation:

- The CRISPR-Cas9 system is packaged into lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [28]. These are tiny fat particles that protect the editing machinery and facilitate its delivery to target cells.

- The Cas9 component used is a compact Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9) or other variant that fits within the LNP's packaging constraints [32].

- Systemic Administration: The LNPs are administered to the patient via a single intravenous (IV) infusion [28] [30].

- Hepatocyte Targeting & Gene Knockout: The LNPs naturally accumulate in the liver. Once inside hepatocytes, the CRISPR system is released and travels to the nucleus [28]. The guide RNA directs Cas9 to introduce a double-strand break in the TTR gene, disrupting its sequence and permanently reducing the production of the misfolded TTR protein responsible for the disease [29] [30].

Diagram 2: Ex Vivo vs. In Vivo CRISPR Therapeutic Workflows. Ex vivo editing modifies patient cells outside the body, while in vivo editing delivers CRISPR directly into the patient's cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful translation of CRISPR therapies from bench to bedside relies on a suite of critical reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used in the development and manufacturing of these advanced therapies.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Therapy Development

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Use in Featured Trials |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Complex of Cas9 protein and guide RNA; enables efficient, transient editing with reduced off-target effects [31]. | Direct delivery into CD34+ HSPCs for ex vivo editing in Casgevy [31]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Non-viral delivery vector for in vivo administration; protects CRISPR components and facilitates cellular uptake [28]. | Systemic delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 for NTLA-2001 (hATTR) [28]. |

| CD34+ HSPC Culture Media | Specialized media formulations that maintain stem cell potency and viability during ex vivo manipulation [31]. | Expansion and maintenance of patient-derived HSPCs during the Casgevy manufacturing process [31]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Viral vector often used as a donor template for HDR; limited packaging capacity but high efficiency [32]. | Preclinical delivery of smaller Cas9 orthologs (e.g., Nme2Cas9, SaCas9) for in vivo editing [32]. |

| Electroporation Systems | Instrumentation that uses electrical pulses to create transient pores in cell membranes for intracellular delivery of editing components [31]. | Introduction of CRISPR RNP into hard-to-transfect primary CD34+ HSPCs in ex vivo protocols [31]. |

The accumulation of clinical data from trials for SCD, TBT, and hATTR provides compelling evidence of CRISPR's therapeutic dominance. Its success is rooted in a powerful combination of high clinical efficacy, demonstrated by durable responses in a majority of patients, and a versatile and streamlined platform that supports both ex vivo and in vivo approaches. While traditional methods like ZFNs and TALENs maintain relevance for niche applications requiring their validated high specificity, the ease of design, cost-effectiveness, and rapid iteration of CRISPR have accelerated its clinical translation and expanded the scope of treatable diseases. As delivery technologies, particularly LNPs, continue to advance, the potential of in vivo CRISPR editing promises to broaden this therapeutic landscape even further.

The advent of programmable nucleases has ushered in a transformative era for molecular biology, enabling precise modifications to DNA sequences across a diverse array of organisms. Among the most prominent tools in this arena are Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR/Cas9 system [8] [33]. While the CRISPR/Cas9 system has gained widespread popularity due to its ease of design and cost-effectiveness, TALENs have carved out a critical and enduring niche in applications demanding the utmost precision, particularly in mitochondrial DNA editing and therapeutic development where specificity is paramount [33] [34].

The fundamental difference between these platforms lies in their mechanism of target recognition. CRISPR/Cas9 is an RNA-guided system, where a short guide RNA (gRNA) directs the Cas9 nuclease to a complementary DNA sequence [16]. In contrast, TALENs utilize a protein-based recognition system; each TALEN is composed of a series of modular, 33-35 amino acid repeats that each recognizes a single DNA base pair through two critical amino acids known as the Repeat Variable Diresidue (RVD) [33] [16]. This structural distinction underpins the unique strengths and weaknesses of each platform.

Key Comparisons: TALENs vs. CRISPR-Cas9

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9

| Feature | TALEN | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Type | DNA-Protein | DNA-RNA |

| Target Site Length | 30-36 bp | ~23 bp |

| Nuclease | FokI (requires dimerization) | Cas9 (functions as a monomer) |

| Off-Target Activity | Low | Moderate to High |

| Design & Assembly | Labor-intensive protein engineering | Simple RNA programming |

| Target Range | Virtually unlimited | Limited by PAM sequence (e.g., 5'-NGG-3') |

| Methylation Sensitivity | Yes (sensitive to CpG methylation) | No |

| Mitochondrial Genome Editing | Straightforward (with MTS) | Extremely challenging |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Key Applications

| Application | TALENs Performance | CRISPR/Cas9 Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity (Off-Target Effects) | High specificity; long target site (≈36 bp) is statistically unique in the genome [33] [16]. | Moderate specificity; gRNA can tolerate mismatches, leading to more off-target effects [33] [16]. |

| Mitochondrial DNA Editing | Highly effective; protein-based editors are easily targeted to mitochondria [35] [34]. | Inefficient; no robust mechanism for importing gRNA into mitochondria [34] [36]. |

| Therapeutic Precision | Preferred for clinical applications requiring validated, high-specificity edits [8] [33]. | Concerns over off-target mutagenesis and immune responses to Cas9 can limit therapeutic use [8] [33]. |

| Efficiency of Indel Formation | High (e.g., ~33% shown in iPSCs) [16]. | Very High (can exceed 70%) [16]. |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited; challenging protein engineering. | Excellent; multiple gRNAs can be used simultaneously [8]. |

The Case for TALENs in Mitochondrial Genome Editing

The Mitochondrial Challenge and the TALEN Solution

Mitochondrial diseases are often caused by heteroplasmic mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), where a mixture of wild-type and mutant mtDNA molecules coexist within a cell [36]. The severity of disease is linked to the proportion of mutant mtDNA, and a key therapeutic strategy is to shift this heteroplasmy ratio toward the wild-type by selectively reducing mutant mtDNA [36]. However, editing the mitochondrial genome presents unique hurdles. Mitochondria have a double membrane and lack efficient mechanisms for importing foreign RNAs, which critically limits the utility of the RNA-guided CRISPR/Cas9 system [34] [36].

TALENs overcome this fundamental barrier. Because they function entirely as proteins, TALENs can be directed to the mitochondria by simply fusing them to a Mitochondrial Targeting Sequence (MTS). This has led to the development of powerful tools like mitoTALENs and, more recently, TALEN-based mitochondrial base editors such as DddA-derived Cytosine Base Editors (DdCBEs) [35] [34] [36]. These systems have demonstrated remarkable success in selectively degrading mutant mtDNA or directly correcting point mutations, thereby restoring cellular energy production and function.

Experimental Evidence and Protocol: Correcting the m.8993T>G Mutation

A seminal 2025 study showcased the therapeutic potential of TALEN-based mitochondrial base editing by correcting the pathogenic m.8993T>G mutation in the MT-ATP6 gene, which causes Neurogenic Muscle Weakness, Ataxia, and Retinitis Pigmentosa (NARP) [35].

- Objective: To reduce the high heteroplasmy level (80%) of the m.8993T>G mutation in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and restore mitochondrial function.

- Editor Design: A split-DddA cytosine base editor (DdCBE) was constructed. Each half was fused to:

- A COX8A Mitochondrial Targeting Sequence (MTS).

- A programmable TALE DNA-binding domain designed to recognize a 16 bp sequence flanking the MT-ATP6 position 8993.

- One half of the split bacterial deaminase DddA [35].

- Delivery & Workflow: The two editor halves were delivered into patient iPSCs via nucleofection. Cells were analyzed over a 30-day period for editing efficiency, off-target effects, and functional recovery [35].

- Results:

- Editing Efficiency: Achieved 35 ± 3% on-target C•G to T•A conversion at day 7, successfully reducing mutant heteroplasmy from 80% to 45% [35].

- Specificity: Demonstrated minimal off-target editing (<0.5%) at ten predicted off-target loci in the mitochondrial genome [35].

- Functional Rescue: Edited cells showed a 25% increase in basal oxygen consumption rate, a 50% improvement in ATP-linked respiration, and a 2.3-fold restoration of ATP synthase activity. Furthermore, neural differentiation was significantly enhanced [35].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and mechanism of action for the TALEN-based mitochondrial base editor in this study.

TALENs in High-Specificity Nuclear Genome Editing

Beyond mitochondrial applications, TALENs maintain a strong position in nuclear genome editing projects where minimizing off-target effects is the primary concern. Comprehensive specificity profiling studies have revealed that TALENs are generally less prone to off-target cleavage than first-generation CRISPR/Cas9 systems [37] [16].

A 2014 study used an in vitro selection method to profile the specificity of 30 unique TALENs against a library of over 10^12 potential off-target sequences [37]. The results demonstrated that TALENs are highly specific across their entire target sequence. The study also led to the engineering of a "Q3" TALEN variant, which exhibited a further 10-fold reduction in average off-target activity in human cells while maintaining robust on-target cleavage [37].

Furthermore, a direct comparative study on editing an integrated EGFP gene in HEK293FT cells found that the choice of editor should be determined by the desired outcome [15]. While paired Cas9 nucleases were more efficient at inducing targeted genomic deletions, TALENs stimulated Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) more efficiently and caused fewer unintended deletions when supplied with a plasmid repair template [15]. This makes TALENs a superior choice for applications requiring precise gene correction or knock-in.

The following diagram outlines the basic mechanism of action for TALENs in the nucleus, highlighting the source of their high specificity.

Essential Reagents and Tools for TALEN Research

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for TALEN-based Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| TALE Repeat Plasmids | Modular building blocks for assembling the DNA-binding domain. | Pre-designed RVD modules (e.g., NI for A, HD for C, NG for T, NN for G) are ligated to target a specific sequence [15] [16]. |

| FokI Nuclease Domain | The cleavage module that induces a double-strand break. | Typically used as an obligate heterodimer (e.g., ELD/KKR variants) to improve specificity and reduce homodimer off-target activity [37]. |