Navigating the Landscape of Gene Editing Off-Target Detection: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Validation

As CRISPR-based gene editing rapidly advances toward clinical applications, the precise detection of off-target effects has become a critical pillar for ensuring therapeutic safety and efficacy.

Navigating the Landscape of Gene Editing Off-Target Detection: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Validation

Abstract

As CRISPR-based gene editing rapidly advances toward clinical applications, the precise detection of off-target effects has become a critical pillar for ensuring therapeutic safety and efficacy. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, detailing the entire workflow of off-target assessment. It covers foundational principles explaining why off-target effects occur, a detailed analysis of in silico, biochemical, and cellular detection methodologies, strategic troubleshooting to enhance editing precision, and essential frameworks for rigorous validation and comparative analysis to meet evolving regulatory standards. The content synthesizes the latest technological advancements and practical considerations to empower the development of safer gene therapies.

Understanding the Roots: Why Off-Target Effects Occur in Gene Editing

The CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and the Source of Imperfection

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common CRISPR-Cas9 Experimental Challenges

1. My knockout efficiency is low. What can I optimize? Low knockout efficiency is a common challenge often stemming from suboptimal sgRNA design, inefficient delivery of CRISPR components, or high activity of DNA repair mechanisms in your cell line [1] [2].

- Solution: Systematically optimize your experiment using the following checklist:

| Troubleshooting Strategy | Specific Actions & Reagents | Key Performance Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Design & Selection [1] [2] | Use multiple algorithms (e.g., Benchling, CCTop) to design 3-5 candidate sgRNAs. Prefer sgRNAs with high predicted on-target scores. Chemically synthesize sgRNAs with 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications for enhanced stability. | INDEL percentage (target >80%); Verification via T7EI assay, ICE, or TIDE analysis [1]. |

| Delivery Method & Conditions [3] [1] [2] | Use ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for transient delivery. For hard-to-transfect cells, use electroporation. Optimize cell-to-sgRNA ratio (e.g., 5 μg sgRNA for 8×10^5 cells). Consider stable Cas9-expressing cell lines for consistent expression. | Transfection efficiency; Cell survival rate post-nucleofection; Cas9 expression levels. |

| Validation & Screening [1] [2] | Employ robust genotyping (T7EI assay, Sanger sequencing analyzed by ICE). Perform functional validation via Western blot to confirm protein loss. Use high-throughput screening to select the most effective sgRNA-cell line pair. | INDEL percentage correlation between ICE and sequencing; Absence of target protein on Western blot. |

2. How can I minimize off-target effects in my experiments? Off-target effects occur when Cas9 cuts at unintended genomic sites with sequences similar to your target, potentially due to mismatches or DNA/RNA bulges [4] [5].

- Solution: Implement a multi-layered strategy to enhance specificity:

| Mitigation Strategy | Technical Approach | Key Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced sgRNA Design [4] | Use truncated sgRNAs with shorter complementarity regions. Employ online tools (e.g., CCTop, Cas-OFFinder) to predict and avoid sgRNAs with high-risk off-target sites. | Reduces tolerance for mismatches between the sgRNA and DNA. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants [3] [4] | Use engineered Cas9 proteins like SpCas9-HF1 or eSpCas9. | Contains mutations that enforce stricter proofreading of the sgRNA-DNA match. |

| Computational Prediction [5] [6] | Utilize advanced prediction tools like CCLMoff, a deep learning framework that uses an RNA language model. | Accurately identifies potential off-target sites for a given sgRNA across diverse datasets, informing better sgRNA selection. |

| Alternative Nucleases [4] | Use Cas9 nickase (makes single-strand breaks) paired with two adjacent sgRNAs, or dCas9-FokI fusions that require dimerization to cut. | Increases the specificity required for a double-strand break, dramatically reducing off-target cleavage. |

3. I suspect cell toxicity from the CRISPR system. How can I address this? Cytotoxicity can result from high concentrations of CRISPR components or prolonged Cas9 activity [3] [2].

- Solution:

- Titrate Components: Start with lower concentrations of Cas9 and sgRNA and gradually increase to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [3].

- Use RNP Complexes: Direct delivery of pre-formed RNP complexes leads to faster editing and clearance, reducing prolonged exposure and toxicity [1] [2].

- Inducible Systems: Use doxycycline-inducible Cas9 (iCas9) systems to control the timing and duration of Cas9 expression, minimizing stress on cells [1].

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Off-Target Effects

A core part of a robust CRISPR workflow is the empirical detection of off-target effects. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies.

Protocol 1: Digenome-seq (In Vitro Detection) Digenome-seq is a sensitive, genome-wide method that detects Cas9 cleavage sites in purified genomic DNA digested in vitro [4].

- Workflow:

- Genomic DNA Isolation: Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from your target cell type.

- In Vitro Digestion: Incubate the purified genomic DNA with Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes programmed with your sgRNA of interest.

- Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS): Subject the digested DNA (and an undigested control) to high-coverage next-generation sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map the sequencing reads to a reference genome and identify sites with a concentration of DNA breaks (cleavage sites) that are present only in the digested sample. These sites represent both on-target and off-target activity [4].

The following diagram illustrates the Digenome-seq workflow:

Protocol 2: BLESS (In Vivo Detection) BLESS (Direct in situ breaks labelling, streptavidin enrichment and next-generation sequencing) detects double-strand breaks (DSBs) directly in fixed cells, providing a snapshot of nuclease activity in a more native cellular context [4].

- Workflow:

- Cell Fixation: Fix cells that have been transfected with your CRISPR/Cas9 system.

- DSB Labeling In Situ: Label the unrepaired DSBs in situ within the nucleus using biotinylated linkers.

- Genomic DNA Extraction & Fragmentation: Extract the genomic DNA and fragment it.

- Enrichment of Biotinylated Fragments: Capture the biotin-labeled DNA fragments (which contain the DSBs) using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Prepare a sequencing library from the enriched fragments and identify off-target sites by mapping the sequences back to the genome [4].

The following diagram illustrates the BLESS workflow:

Protocol 3: GUIDE-Seq (In Vivo Detection via Integration) GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing) utilizes the integration of a short, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag into DSB sites in vivo to mark them for sequencing [5].

- Workflow:

- Co-delivery of CRISPR and Tag: Co-transfect cells with your CRISPR/Cas9 components and a defined, short dsODN tag.

- Tag Integration: The dsODN tag is captured and integrated into DSB sites (both on-target and off-target) by the cell's endogenous repair machinery.

- Genomic DNA Extraction & Shearing: Extract genomic DNA and shear it.

- Enrichment of Tag-Containing Fragments: Use PCR with primers specific to the dsODN tag to enrich for fragments that contain the integrated tag.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence the enriched library to identify the genomic locations where the tag integrated, revealing the spectrum of Cas9 cleavage sites [5].

The following diagram illustrates the GUIDE-seq workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and reagents essential for implementing the troubleshooting strategies and detection protocols discussed above.

| Item | Function & Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants [3] [4] | Engineered for reduced off-target cleavage while maintaining high on-target activity. | SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9, xCas9. |

| Cas9 Nickase [4] | A mutant Cas9 that cuts only one DNA strand; requires two adjacent sgRNAs for a DSB, dramatically improving specificity. | Useful for precise editing and reducing off-target effects. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA [1] | Enhanced stability within cells, leading to increased editing efficiency and potentially reduced variability. | sgRNAs with 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at the 5' and 3' ends. |

| dsODN Tag [5] | A short, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide used as a tag for DSB sites in the GUIDE-seq protocol. | Essential reagent for the GUIDE-seq method to mark and later identify cleavage sites. |

| Computational Prediction Tools [5] [6] | In silico platforms for predicting potential off-target sites during the sgRNA design phase. | CCLMoff (deep learning-based), Cas-OFFinder (alignment-based), CCTop (formula-based). |

| Stable Inducible Cas9 Cell Lines [1] | Cell lines with integrated, inducible Cas9 (e.g., via a Tet-On system) for controlled, uniform expression, minimizing toxicity and variability. | Doxycycline-inducible SpCas9 hPSC lines (hPSCs-iCas9). |

| Ethyl 3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzoate | Ethyl 3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzoate, CAS:6178-44-5, MF:C12H16O5, MW:240.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Prostaglandin D2-1-glyceryl ester | Prostaglandin D2-1-glyceryl ester, MF:C23H38O7, MW:426.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary molecular factors that cause CRISPR/Cas9 off-target effects? The primary factors are mismatches between the sgRNA and DNA sequence, flexibility in Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) recognition, and the presence of DNA or RNA bulges. The CRISPR/Cas9 system can tolerate imperfect complementarity, leading to cleavage at unintended genomic sites that resemble the intended target [4] [7] [8]. Mismatches in the seed region (PAM-proximal 10–12 nucleotides) are particularly impactful, though mismatches in the PAM-distal region can also be tolerated [4] [7].

2. How does the position of a mismatch in the sgRNA influence its impact? The impact of a mismatch is highly position-dependent. The seed region, located closest to the PAM, is the most critical for specific recognition and cleavage [4]. Mismatches in this PAM-proximal region are less likely to be tolerated and can prevent efficient binding. In contrast, mismatches near the distal end (further from the PAM) are more likely to be tolerated and result in off-target activity [4] [7].

3. What is PAM flexibility, and how does it contribute to off-target effects? While the commonly used SpCas9 nuclease is designed to recognize a canonical "NGG" PAM sequence, it has been shown to tolerate non-canonical variants like "NAG" and "NGA" [4] [8]. This flexibility means that many more potential off-target sites exist throughout the genome where Cas9 can bind and cleave, even if the PAM sequence is not a perfect match [4]. The development of PAM-free or less restrictive systems, such as SpRY, further expands the targetable genome but may also increase the potential for off-target effects [4].

4. What are DNA/RNA bulges, and why are they problematic? DNA/RNA bulges refer to extra nucleotide insertions that arise due to imperfect complementarity between the sgRNA and the target DNA [4]. Even in the presence of such bulges, where the sequences do not perfectly align, Cas9 can still cleave the DNA at these mismatched sites, resulting in off-target effects [4].

5. What strategies can be used to minimize off-target effects driven by these factors? Several strategies have been developed to enhance specificity:

- High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Using engineered Cas9 proteins like SpCas9-HF1 or eSpCas9, which are designed to be less tolerant of mismatches [4] [9].

- Optimized sgRNA Design: Truncating the sgRNA length by 1-2 nucleotides can increase specificity and reduce mismatch tolerance [4] [8]. Using chemically modified synthetic sgRNAs can also improve stability and specificity [9] [10].

- Alternative CRISPR Systems: Employing Cas9 nickases (which create single-strand breaks) or dCas9-FokI fusions, which require two adjacent binding events for a double-strand break, significantly improves precision [4] [9].

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery: Delivering pre-assembled Cas9 protein and sgRNA complexes (RNPs) has been shown to reduce off-target effects compared to plasmid-based delivery, as it shortens the exposure time of cells to the editing machinery [10] [8].

Quantitative Data on Off-Target Factors

Table 1: Impact of Mismatch Position on Cleavage Efficiency

| Mismatch Position Relative to PAM | Tolerance Level & Impact on Cleavage |

|---|---|

| Seed Region (PAM-proximal, ~nt 1-12) | Low tolerance. Mismatches, especially in positions 1-8, are most likely to prevent efficient binding and cleavage [4] [7]. |

| PAM-distal Region (~nt 18-20) | Higher tolerance. Off-target cleavage can occur even with up to six base mismatches in this region [4] [7]. |

Table 2: PAM Sequence Specificity of Different Cas9 Variants

| Cas9 Variant | Recognized PAM Sequence | Implication for Off-Target Risk |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (Standard) | NGG | Moderate risk due to tolerance of non-canonical PAMs like NAG and NGA [4] [8]. |

| SaCas9 | NNGRRT | Longer, more complex PAM reduces occurrence frequency in the genome, narrowing the target range and improving specificity [4]. |

| SpCas9-NG | NG | Less restrictive PAM than SpCas9, expanding target range but potentially increasing off-target risk [4]. |

| SpRY | NRN > NYN | Nearly PAM-free, offering great targeting flexibility but requiring careful off-target assessment [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Detection

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing (GUIDE-seq) GUIDE-seq is a cellular method that detects double-strand breaks (DSBs) directly in living cells, providing high biological relevance [11] [12].

- Transfection: Co-deliver CRISPR/Cas9 components (e.g., as plasmid or RNP) and a double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag into cells.

- Tag Integration: The dsODN tag is incorporated into CRISPR-induced DSBs via the cellular non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells and isolate genomic DNA.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Fragment the DNA and perform PCR amplification using primers specific to the integrated dsODN tag. Prepare libraries for next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Data Analysis: Map the sequenced tags to the reference genome to identify all sites of DSB formation, both on-target and off-target [11] [12].

Protocol 2: Circularization for In Vitro Reporting of Cleavage Effects by Sequencing (CIRCLE-seq) CIRCLE-seq is a sensitive, biochemical, cell-free method that can detect rare off-target sites by enriching for cleaved fragments [11] [12].

- DNA Purification and Shearing: Isolate genomic DNA and shear it into fragments.

- Circularization: Ligate the sheared DNA fragments into circular molecules.

- In Vitro Cleavage: Incubate the circularized DNA library with pre-assembled Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Exonuclease Digestion: Treat the reaction with an exonuclease that digests linear DNA but not circular DNA. This step enriches for linear DNA fragments generated by Cas9 cleavage.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Break the circles at the cleavage sites, add sequencing adapters, and perform NGS.

- Data Analysis: Identify sequencing reads with breaks that align to the reference genome, revealing potential off-target cleavage sites [11] [12].

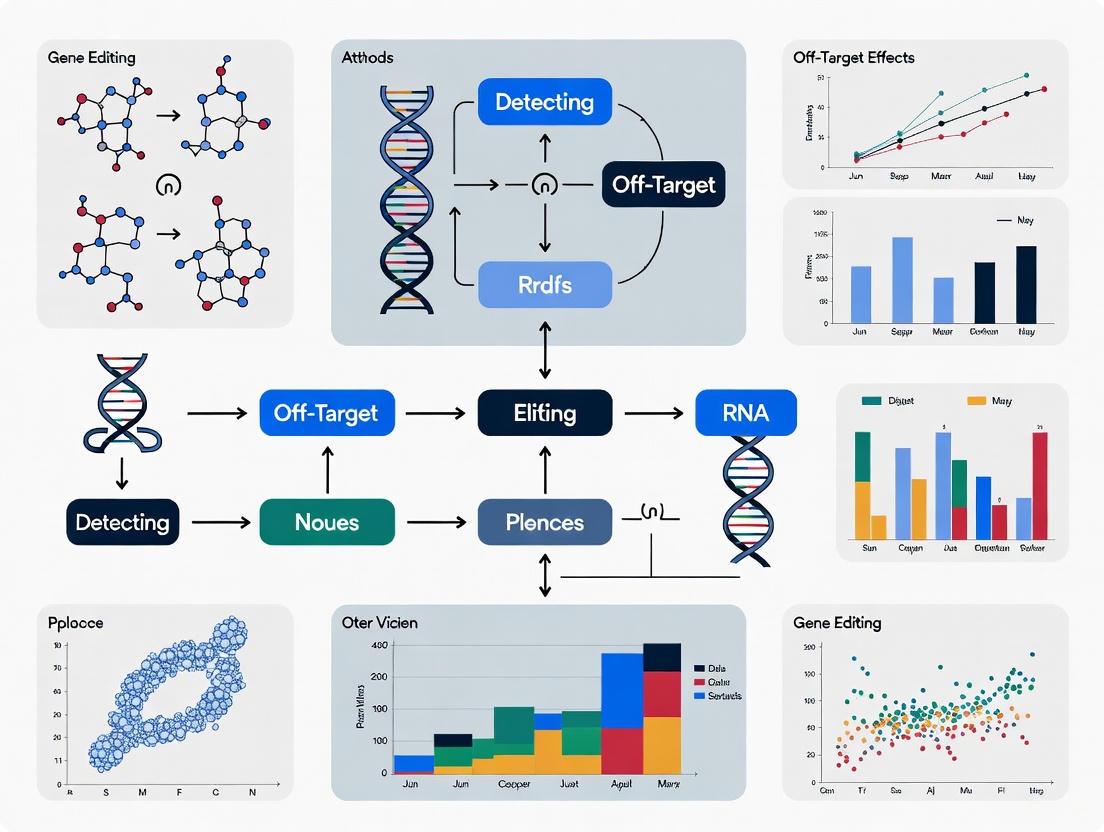

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Molecular pathway of on-target and off-target CRISPR/Cas9 activity, showing key decision points where mismatches, bulges, and PAM flexibility lead to errors.

Diagram 2: Decision workflow for selecting the appropriate off-target detection method based on research goals and context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Off-Target Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) | Engineered nucleases with reduced mismatch tolerance; used to minimize off-target cleavage from the outset [4] [9]. | Balance between enhanced specificity and potential reduction in on-target efficiency. |

| Chemically Modified Synthetic sgRNA | Improved stability and reduced innate immune response; certain modifications can also reduce off-target editing [9] [10]. | Modifications like 2'-O-methyl (2'-O-Me) at terminal residues are common. Prefer over in vitro transcribed (IVT) guides for sensitive applications. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and sgRNA; shortens editing exposure time in cells, reducing off-target effects compared to plasmid delivery [10] [8]. | Ideal for "DNA-free" editing and protocols requiring high precision and low toxicity. |

| Tagmented Oligos (for GUIDE-seq) | Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides that are incorporated into DSBs, enabling genome-wide mapping of cleavage sites in cells [11] [12]. | Critical for cellular, unbiased detection methods. Efficiency of tag integration can affect assay sensitivity. |

| Deep Learning Prediction Tools (e.g., CCLMoff, DNABERT-Epi) | Computational models that predict potential off-target sites by analyzing sgRNA sequence and epigenetic context; used for pre-screening and guide selection [5] [13]. | Models trained on diverse datasets (in vitro and in cellula) generally have better generalization and accuracy. |

| 2-Benzoylbenzoic Acid | 2-Benzoylbenzoic Acid, CAS:85-52-9, MF:C14H10O3, MW:226.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,3,7-Trihydroxy-2-methoxyxanthone | 1,3,7-Trihydroxy-2-methoxyxanthone|Research-Chemical | High-purity 1,3,7-Trihydroxy-2-methoxyxanthone for research applications. Explore its bioactivity for your studies. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

The Critical Role of the Seed Region in DNA Recognition

FAQs: Core Concepts of the Seed Region

Q1: What is the seed region in nucleic acid-guided systems? The seed region is a short, crucial sequence at the 5' end of a guide RNA or single-guide RNA (sgRNA). In RNA silencing, the core seed sequence typically spans nucleotides 2–7 of the guide strand, and to a lesser extent, can include nucleotide 8 [14]. This region serves as a primary anchor site for initial target recognition. In CRISPR-Cas9 systems, the seed region is also the portion of the sgRNA that exhibits the least tolerance for mismatches when binding to its DNA target, making it critical for specificity [9].

Q2: Why is the seed region so critical for specificity and off-target effects? The seed region is critical because it provides an enhanced-affinity anchor site that nucleates target recognition. Association of the guide strand with the PIWI/MID domain of an Argonaute protein in RISC can enhance the interaction affinity over the seed sequence by up to 300-fold [14]. In CRISPR systems, the Cas9 nuclease can tolerate between three and five base pair mismatches in other parts of the guide sequence, but mismatches within the seed region, particularly at position 3, are amplified and lead to significantly reduced off-target activity [14] [9]. This amplified discrimination means that proper seed binding is essential for accurate targeting.

Q3: How do protein interactions enhance seed region function? Structural studies show that the seed region of the guide strand is anchored via its phosphodiester backbone to the PIWI/MID domain of effector proteins like Argonaute or Cas9 [14] [15]. This association generates an enhanced affinity anchor site by reducing the entropy penalty for interaction, likely through immobilization or preordering of the guide strand [14]. For PAM-relaxed SpCas9 variants like SpRY, this preference is mediated by specific interactions with amino acid residues such as A61R and A1322R [15].

Q4: Are seed region rules consistent across different editing platforms? While the fundamental principle of a privileged 5' anchor region is conserved, specific characteristics vary. In RNAi/miRNA systems, the seed region (nucleotides 2-7/8) of the guide RNA is paramount for target recognition [14]. In CRISPR-Cas9, the seed region's importance is maintained even in PAM-relaxed variants like SpG and SpRY, which exhibit a preference for the seed region to compensate for relaxed PAM recognition [15]. This demonstrates how different nucleic acid-guided systems have evolutionarily converged on the strategic use of a seed region for efficient target searching.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Seed Region Experimental Problems

Problem: High Off-Target Editing Rates

Symptoms: Unintended mutations at sites with homology to your target sequence, particularly in regions with similar seed sequences but divergent 3' regions.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal gRNA design with high similarity to multiple genomic sites | Redesign gRNA using in silico tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder, CRISPOR) to select guides with unique seed sequences and high on-target/off-target scores [16] [9] [17]. | Use GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq to experimentally profile off-target sites genome-wide [16] [17]. |

| Using wild-type Cas9 with high mismatch tolerance | Switch to high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9, eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) that enforce stricter seed recognition [9] [17]. | Compare editing profiles of wild-type and high-fidelity Cas9 using targeted sequencing of predicted off-target sites. |

| Prolonged expression of editing components | Use Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for transient delivery rather than plasmid-based expression to limit activity duration [9]. | Measure indel frequencies over time; RNP delivery typically shows reduced off-targets compared to plasmid transfection. |

| High GC content outside seed compromising specificity | Design gRNAs with optimal (40-60%) GC content overall, ensuring perfect complementarity in the seed region [9]. | Test multiple candidate gRNAs with varying GC content in a reporter assay to assess specificity. |

Problem: Low On-Target Editing Efficiency

Symptoms: Poor gene modification rates at the intended target site despite apparently good gRNA design.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin inaccessibility at target site | Select target sites in open chromatin regions using ATAC-seq or DNase-seq data; consider using chromatin-modulating compounds [16]. | Perform Cas9 ChIP-seq to verify binding accessibility; use FACS or Western blot to quantify editing efficiency. |

| Suboptimal PAM or seed sequence context | For CRISPR, choose different PAM sites; ensure no secondary structure in seed region; use algorithms that predict on-target efficiency [15] [3]. | Test multiple gRNAs targeting the same gene; use T7E1 assay or Sanger sequencing to quantify editing efficiency. |

| Ineffective delivery of editing components | Optimize delivery method (electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) for your specific cell type; validate RNP complex formation [3]. | Use immunofluorescence to detect Cas9 nuclear localization; measure guide RNA expression levels by qRT-PCR. |

Problem: Inconsistent Editing Outcomes Across Cell Types

Symptoms: The same gRNA produces different editing efficiencies and specificities in different biological models.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-type specific chromatin organization | Validate gRNA performance in your specific experimental model rather than relying solely on predictions from other cell types [16] [17]. | Perform ATAC-seq in your specific cell type to identify accessible regions; use Western blot to confirm Cas9 expression. |

| Variable DNA repair machinery activity | Consider cell cycle synchronization; use different Cas9 formats (nickase, base editors) that leverage alternative repair pathways [17]. | Assess repair outcomes by sequencing; measure cell cycle distribution by FACS. |

| Differential expression of key pathway components | Use consistent, controlled delivery methods (RNP preferred); select cell models with robust DNA repair capabilities [3]. | Perform RNA-seq to characterize DNA repair pathway expression; use isogenic cell lines for comparisons. |

Table 1: Seed Region Binding Affinity and Discrimination Power

| Parameter | Value | Experimental System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding affinity enhancement | Up to 300-fold | AfPiwi-guide RNA complex [14] | PMC2642989 |

| Mismatch discrimination | Amplified at position 3 | Archaeoglobus fulgidus PIWI/MID domain [14] | PMC2642989 |

| Cas9 mismatch tolerance | 3-5 mismatches outside seed region | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 [9] | Synthego Blog |

| Core seed sequence length | Nucleotides 2-7 (extends to nt 8) | microRNA/RNA silencing [14] | PMC2642989 |

Table 2: Detection Methods for Seed Region-Dependent Off-Target Effects

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Key Consideration for Seed Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| GUIDE-seq | Integrates dsODNs into DSBs for sequencing | High (low false positive rate) | Identifies off-targets with seed similarity [16] [17] |

| CIRCLE-seq | Circularized genomic DNA + Cas9 RNP in vitro | Highly sensitive | Detects seed-matched off-targets without cellular context [16] [17] |

| Digenome-seq | In vitro Cas9 digestion of purified genomic DNA | Highly sensitive | Requires high sequencing coverage; identifies seed-mediated cleavage [16] |

| CHANGE-seq | In vitro method with sequencing adapter integration | Highly sensitive | Unbiased detection of seed-dependent off-targets [17] |

| LAM-HTGTS | Detects chromosomal translocations from DSBs | Targeted (requires bait sites) | Identifies pathogenic rearrangements from seed-mediated off-targets [16] [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Seed Region-Dependent Off-Target Effects Using GUIDE-seq

Purpose: To genome-widely identify off-target editing sites, particularly those driven by seed region homology.

Reagents Needed:

- GUIDE-seq dsODN tag (commercially available)

- Cas9 nuclease and sgRNA (as RNP or expression plasmid)

- PCR and NGS library preparation reagents

- Cells of interest and appropriate culture media

- Transfection reagent (lipofectamine CRISPRMAX or electroporation system)

Procedure:

- Design and synthesize sgRNA: Ensure optimal seed region sequence with minimal off-target potential using prediction tools like Cas-OFFinder [16].

- Co-deliver editing components: Transfect cells with Cas9-sgRNA complex along with GUIDE-seq dsODN tag. For human primary T cells, use ~100,000 cells, 100pmol Cas9, 100pmol sgRNA, and 100pmol dsODN [16] [17].

- Harvest genomic DNA: Extract high molecular weight genomic DNA 72 hours post-transfection.

- Library preparation and sequencing:

- Shear gDNA to ~500bp fragments

- Prepare sequencing libraries with GUIDE-seq-specific primers

- Perform high-throughput sequencing (Illumina recommended)

- Data analysis:

- Map sequenced reads to reference genome

- Identify GUIDE-seq tag integration sites

- Filter and validate bona fide off-target sites

- Particularly note sites with seed region homology but 3' mismatches

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low tag integration: Optimize dsODN concentration and transfection efficiency

- High background: Include proper negative controls (transfection without Cas9)

- Validation: Confirm top off-target sites by targeted amplicon sequencing

Protocol 2: In Vitro Cleavage Specificity Profiling with CIRCLE-seq

Purpose: Highly sensitive, cell-free identification of potential seed region-dependent off-target sites without cellular constraints.

Reagents Needed:

- Purified genomic DNA from target cells

- Cas9 nuclease protein and in vitro transcribed sgRNA

- CIRCLE-seq library preparation kit or components

- DNA shearing equipment (sonicator or nebulizer)

- ATP-dependent DNA degradase (plasmid-safe ATP-dependent DNase)

Procedure:

- Genomic DNA preparation:

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA

- Shear DNA to ~300bp fragments using covaris sonicator

- DNA circularization:

- End-repair and ligate sheared DNA into circular molecules using T4 DNA ligase

- Treat with plasmid-safe ATP-dependent DNase to linearize DNA

- In vitro cleavage:

- Incubate circularized DNA library with preassembled Cas9-sgRNA RNP complex

- Use titration of RNP complex (e.g., 100nM, 50nM, 10nM) to assess cleavage efficiency

- Library preparation and sequencing:

- End-repair cleaved fragments

- Add sequencing adapters and amplify with indexed primers

- Sequence on appropriate platform (Illumina recommended)

- Bioinformatic analysis:

- Map cleavage sites to reference genome

- Identify sites with seed region complementarity

- Rank off-target sites by read count and mismatch position

Technical Notes:

- This method is particularly sensitive for detecting seed-matched off-target sites that might be missed in cellular assays due to chromatin inaccessibility [16]

- Always include a no-Cas9 control to identify background cleavage

- Validation of top candidate sites in cellular models is recommended

Visualization: Seed Region Function and Off-Target Detection

Diagram 1: Seed-Centric gRNA Design and Validation Workflow - This workflow illustrates the critical steps for designing and validating gRNAs with optimal seed region properties to minimize off-target effects, incorporating both computational and experimental approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Seed Region Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Seed Region Studies |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | HiFi Cas9, eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1 [17] | Reduce seed region-dependent off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity |

| Chemical Modified gRNAs | 2'-O-methyl-3'-phosphonoacetate, bridged nucleic acids [17] | Enhance stability and specificity of seed region binding |

| Off-Target Detection Kits | GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq, SITE-seq kits [16] [17] | Experimental validation of seed-mediated off-target effects |

| In Silico Prediction Tools | Cas-OFFinder, CRISPOR, FlashFry [16] [9] | Computational prediction of seed region-dependent off-target sites |

| Cell Delivery Systems | Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX, Neon Electroporation System [18] [3] | Efficient RNP delivery to minimize duration of nuclease activity and off-target editing |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address challenges related to chromatin state and genetic variation in gene editing experiments, framed within the broader context of detecting off-target effects.

FAQs: Chromatin and Genetic Variation in Gene Editing

How does chromatin state influence CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency? Chromatin state significantly impacts CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency. Heterochromatin (transcriptionally inactive, tightly packed DNA) presents a substantial barrier to Cas9 access and cutting, leading to reduced editing efficiency compared to euchromatin (open, active DNA) [19] [20]. The local chromatin environment at the cut site also influences the DNA repair pathway balance, with heterochromatic regions more frequently repaired via error-prone microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) [19].

What specific chromatin modifications are linked to variable editing outcomes? Enhancer-associated histone modifications, such as H3K27ac and H3K4me1, show the highest degree of variability across individuals [21]. This natural variation can lead to differences in how accessible a genomic region is to gene editing tools. The repressive mark H3K27me3 is also highly variable, particularly in "poised" or bivalent regulatory elements [21].

How can genetic variation between individuals lead to unexpected editing results? Genetic variations, like single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), can create or disrupt potential off-target sites by altering the DNA sequence [16] [22]. A SNP at your intended target site might reduce on-target efficiency by creating a mismatch with your guide RNA (gRNA). Conversely, a SNP elsewhere in the genome might create a novel, unintended sequence that perfectly matches your gRNA, leading to an off-target cut [22].

What practical steps can I take to improve editing in refractory chromatin regions? Pretreating cells with specific chromatin-modifying drugs, such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, can loosen chromatin compaction and improve Cas9 access [19]. The effectiveness of these drugs is highly dependent on the local chromatin context. For example, HDAC inhibitor PCI-24781 improved editing efficiency across all heterochromatin types, while apicidin was only effective in euchromatin and H3K27me3-marked regions [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency in Heterochromatin

Potential Cause: The target site is located within tightly packed, transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin, physically blocking Cas9 binding [19] [20].

Solutions:

- Epigenetic Pretreatment: Treat cells with chromatin-modifying drugs prior to editing.

- Protocol: Dose cells with an HDAC inhibitor (e.g., PCI-24781 at 10 µM, 1 µM, or 100 nM) 24 hours before transfection with CRISPR components. Re-dose 24 hours post-transfection and culture for an additional 48-72 hours before analysis [19].

- Validation: Use qPCR or a CUT&RUN assay on treated vs. untreated samples to confirm an increase in active chromatin marks (e.g., H3K27ac) at the target locus [23].

- gRNA Redesign: If possible, redesign gRNAs to target exons within the same gene that are located in more accessible euchromatic regions. Use epigenome browsers (like Ensembl or WashU Epigenome Browser) to identify regions with high H3K27ac or low H3K27me3 signals [24] [21].

Problem: High Off-Target Editing Due to Genetic Variation

Potential Cause: Common genetic variations in your cell line or population (e.g., SNPs) create novel, unintended off-target sites with high complementarity to your gRNA [16] [22].

Solutions:

- Use Population-Aware In Silico Prediction:

- Protocol: When designing your gRNA, use prediction tools like Cas-OFFinder that allow you to input a custom genome sequence or a panel of genomes representing the genetic diversity of your model system. This helps identify off-target sites specific to your experimental context [16].

- Follow-up: Empirically test all high-scoring potential off-target sites, especially those created by SNPs, using amplicon sequencing.

- Employ High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Use engineered Cas9 variants like eSpCas9 or SpCas9-HF1, which have reduced tolerance for gRNA-DNA mismatches, to minimize cleavage at these SNP-generated off-target sites [16] [22].

- Validate with an Empirical Method: Use highly sensitive, unbiased detection methods like GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq.

Problem: Inconsistent Editing Outcomes Across Cell Lines or Donors

Potential Cause: Underlying genetic and epigenetic variation between the cell lines or individual donors leads to differences in chromatin accessibility and gRNA binding [21] [25].

Solutions:

- Characterize Cellular Context:

- Adapt gRNA Design: Avoid designing gRNAs where the seed sequence (PAM-proximal 10-12 bases) overlaps with a known common SNP [22].

- Consider Epigenome Editing: If the goal is gene regulation, consider using a dCas9-epigenetic effector system (e.g., dCas9-p300 for activation, dCas9-KRAB for repression) instead of cutting. The outcomes of these systems can also be context-dependent but offer an alternative perturbation method [23].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Testing the Impact of an HDAC Inhibitor on Editing

This protocol systematically evaluates how a chromatin-modifying drug affects Cas9 editing efficiency and repair outcomes in different chromatin contexts [19].

Protocol: Unbiased Off-Target Detection with GUIDE-seq

This protocol provides a robust method for empirically identifying off-target sites in your specific cellular context [16] [22].

Quantitative Data on Chromatin and Editing

Table 1: Variability of Chromatin Features Across Individuals [21] This table summarizes the extent of natural variation found in different chromatin marks and features in human lymphoblastoid cell lines, which can predispose certain genomic regions to variable editing outcomes.

| Chromatin Feature | Relative Variability (vs. Gene Expression) | Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancer Marks (H3K27ac, H3K4me1) | Highest | Individual-specific active/repressed states; enriched for motif-disrupting SNPs. |

| Promoter Marks (H3K4me3) | High | More variable at enhancers than at core promoters. |

| Repressive Marks (H3K27me3) | High | Most variable in "poised" or bivalent states. |

| Gene Body Marks (H3K36me3) | Low | Relatively stable across individuals. |

| Gene Expression | Lowest (Baseline) | Remains stable despite enhancer variability; changes only when >60% of a gene's enhancers vary. |

Table 2: Chromatin-Dependent Effects of Selected Epigenetic Drugs on Cas9 Editing [19] This table provides examples of drugs that modulate editing efficiency in a manner that depends on the local chromatin environment.

| Drug Example | Target | Impact on Cas9 Editing Efficiency | Chromatin Context Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCI-24781 | HDAC inhibitor | Improves efficiency | Effective across all types of heterochromatin. |

| Apicidin | HDAC inhibitor | Improves efficiency | Only effective in euchromatin and H3K27me3-marked regions. |

| NU7441 | DNA-PKcs inhibitor (NHEJ inhibitor) | Alters repair outcome (MMEJ:NHEJ ratio) | Used as a positive control for NHEJ inhibition. |

| Mirin | MRE11 inhibitor (MMEJ inhibitor) | Alters repair outcome (MMEJ:NHEJ ratio) | Used as a positive control for MMEJ inhibition. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Context-Dependent Effects

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., PCI-24781) | Loosen chromatin compaction by increasing histone acetylation. | Improving Cas9 access and cutting efficiency in heterochromatic regions [19]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 (e.g., eSpCas9) | Engineered Cas9 variant with reduced tolerance for gRNA-DNA mismatches. | Minimizing off-target effects at sites with high sequence similarity, including those created by SNPs [16] [22]. |

| dsODN Tag (for GUIDE-seq) | Short, double-stranded DNA molecule that integrates into DSBs. | Experimental, genome-wide identification of off-target cleavage sites in living cells [16] [22]. |

| Chromatin-Modifying Effectors (e.g., dCas9-p300) | Fusions of catalytically dead Cas9 with epigenetic writer domains. | Systematically studying the causal role of specific chromatin marks (e.g., H3K27ac) on transcription and editing [23]. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder) | Algorithmic nomination of potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity. | Initial, sgRNA-dependent assessment of off-target risk, which can be customized for user-provided genomes or genetic variants [16]. |

| 3,4-Dihydroxy-2-methoxyxanthone | 3,4-Dihydroxy-2-methoxyxanthone, MF:C14H10O5, MW:258.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Emixustat Hydrochloride | Emixustat Hydrochloride | Emixustat hydrochloride is a potent RPE65 inhibitor for researching retinal diseases like Stargardt disease and geographic atrophy. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

What are CRISPR off-target effects and why are they a primary concern in therapeutic development?

A: CRISPR off-target effects refer to unintended edits at locations in the genome that are genetically similar to the intended target site [9]. These are a major concern because they can confound research results and, in a clinical setting, pose critical patient safety risks [8] [9]. Unintended mutations can disrupt essential genes, including tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes, potentially leading to genomic instability or carcinogenesis [8] [26]. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require comprehensive off-target characterization for therapies moving into clinical trials [8] [26].

What types of unintended genetic alterations beyond small indels should I be worried about?

A: Beyond small insertions or deletions (indels), CRISPR editing can lead to larger, more complex structural variations (SVs) [26]. These include:

- Kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions at the on-target site [26].

- Chromosomal translocations between different chromosomes [26].

- Chromosomal losses or truncations [26].

- Chromothripsis, a catastrophic event where chromosomes are shattered and rearranged [26]. These SVs are a pressing safety concern as they can delete critical regulatory elements or genes with profound consequences [26].

My editing efficiency is high, but my phenotypic results are inconsistent. Could off-target effects be the cause?

A: Yes. In functional genomics studies, off-target editing can make it difficult to determine if an observed phenotype is the result of the intended on-target edit or due to unintended mutations at other genomic loci [9]. It is crucial to use carefully designed gRNAs with low predicted off-target activity and to verify the genotype of your cell lines through comprehensive sequencing.

Do high-fidelity Cas9 variants completely eliminate the risk of structural variations?

A: No. While high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) or paired nickase strategies are excellent for reducing off-target cleavage activity, they can still introduce substantial on-target aberrations, including structural variations [26]. Therefore, using these improved nucleases does not eliminate the need for thorough genomic integrity screening.

How do strategies to enhance HDR, like using DNA-PKcs inhibitors, impact genomic integrity?

A: Strategies that inhibit key components of the NHEJ pathway, such as the DNA-PKcs inhibitor AZD7648, to enhance HDR can have unintended consequences. Recent studies show these inhibitors can aggravate genomic aberrations, leading to a significant increase in large deletions and chromosomal translocations [26]. This can also lead to an overestimation of HDR efficiency in standard assays, as large deletions may remove primer binding sites used in short-read sequencing, making the aberrant events "invisible" [26].

Experimental Protocols for Off-Target Detection

A thorough off-target assessment strategy often combines in silico prediction with empirical methods.

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Off-Target Detection Using GUIDE-seq

GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by sequencing) is a sensitive, cell-based method for identifying off-target sites in vivo [27].

Detailed Methodology:

- Oligonucleotide Tag Integration: Co-deliver your CRISPR-Cas9 components (e.g., Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA) along with a short, double-stranded oligonucleotide tag (dsODN) into the target cells.

- Tag Capture at DSBs: When a double-strand break (DSB) occurs—whether on-target or off-target—the cellular repair machinery integrates the dsODN tag into the break site.

- Genomic DNA Preparation and Enrichment: Harvest cells 2-3 days post-transfection. Extract genomic DNA and shear it by sonication. Enrich for tag-integrated fragments using PCR.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare a next-generation sequencing (NGS) library from the enriched fragments.

- Data Analysis: Map the sequencing reads back to the reference genome. Off-target sites are identified as genomic locations where the dsODN tag has been integrated, indicating a DSB occurred at that site [27].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: In Vitro Off-Target Detection Using CIRCLE-seq

CIRCLE-seq (Circularization for In Vitro Reporting of Cleavage Effects by Sequencing) is a highly sensitive in vitro method that can detect potential off-target sites without the constraints of cellular context [8] [27].

Detailed Methodology:

- Genomic DNA Isolation and Shearing: Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from your cell type of interest and shear it to a desired fragment size.

- DNA Circularization: Ligate the sheared genomic DNA into circular molecules.

- In Vitro Cleavage: Incubate the circularized DNA library with the Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. The Cas9 nuclease will introduce DSBs at sites complementary to the gRNA.

- Linear Fragment Enrichment: Treat the reaction with an exonuclease to degrade all non-cleaved, circular DNA. The linear fragments resulting from Cas9 cleavage are protected and enriched.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare an NGS library from the enriched linear fragments and sequence them.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map the sequencing reads to the reference genome to identify sequences that have been cleaved by Cas9, revealing a comprehensive profile of potential off-target sites [8] [27].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Comparison of Off-Target Detection Methods

The choice of detection method depends on your experimental needs, balancing sensitivity, throughput, and biological context. The table below summarizes key characteristics of major techniques.

| Method | Principle | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GUIDE-seq [27] | Integration of a dsODN tag into DSBs in vivo. | Unbiased, genome-wide profiling in a cellular context. | Requires efficient delivery of the dsODN into cells. | Identifying biologically relevant off-target sites in cell cultures. |

| CIRCLE-seq [8] [27] | In vitro cleavage of circularized genomic DNA by Cas9 RNP. | Extremely high sensitivity; not limited by cell viability or delivery. | Purely in vitro; may detect sites not accessible in cells. | Comprehensive, ultra-sensitive screening of gRNA specificity before cellular experiments. |

| Digenome-seq [27] | In vitro cleavage of purified genomic DNA followed by whole-genome sequencing. | Unbiased, genome-wide; no cloning required. | Lower sensitivity compared to CIRCLE-seq; in vitro context. | Genome-wide off-target identification. |

| DISCOVER-seq [27] | Relies on the recruitment of DNA repair factors (e.g., MRE11) to DSBs. | Identifies off-targets in vivo; applicable to any organism. | Relies on the endogenous repair machinery. | Detecting off-target edits in vivo, including in animal models. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [8] | Direct sequencing of the entire genome before and after editing. | Most comprehensive method; can detect all mutation types, including SVs. | Expensive; may miss low-frequency events due to sequencing depth. | Gold-standard safety assessment for clinical therapies; detecting large SVs. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) [8] [26] | Engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced mismatch tolerance, lowering off-target cleavage. | Often trade reduced off-target activity for slightly lower on-target efficiency. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNAs [9] | sgRNAs with 2'-O-methyl and/or phosphorothioate modifications to increase stability and reduce off-target effects. | Modifications can improve gRNA performance by enhancing nuclease resistance and editing specificity. |

| Cas9 Nickase (nCas9) [26] | A Cas9 variant that creates single-strand breaks instead of DSBs. Used in pairs to mimic a DSB, drastically reducing off-target activity. | Requires careful design of two adjacent gRNAs. Off-target nicking can still occur. |

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) [26] | Small molecules that inhibit the NHEJ pathway to promote HDR. | Can exacerbate large structural variations and chromosomal translocations; use with caution. |

| CAST-Seq Assay [26] | A method specifically designed to identify and quantify chromosomal rearrangements (translocations, large deletions) resulting from CRISPR editing. | Critical for a comprehensive genotoxicity assessment beyond small indels. |

| Bioinformatics Tools (e.g., CRISPOR, GuideScan) [8] [9] | Computational software for designing sgRNAs and predicting potential off-target sites in silico before experiments. | Essential first step for gRNA selection; predictions should be validated empirically. |

| 42-(2-Tetrazolyl)rapamycin | 42-(2-Tetrazolyl)rapamycin, CAS:221877-56-1, MF:C52H79N5O12, MW:966.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Cinnamoyl-3-hydroxypyrrolidine | 1-Cinnamoyl-3-hydroxypyrrolidine | Research-grade 1-Cinnamoyl-3-hydroxypyrrolidine for antifungal studies. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. |

Mechanisms and Consequences of Off-Target Effects

Understanding how off-target effects occur and their potential downstream impacts is crucial for risk assessment. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways from CRISPR delivery to functional consequences.

The Detection Toolkit: In Silico, Biochemical, and Cellular Methods for Off-Target Identification

In CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, off-target effects occur when the system acts on untargeted genomic sites, creating cleavages that can lead to unintended and potentially adverse outcomes [16]. These effects are a significant concern, particularly in clinical applications, as they can confound experimental results and pose critical safety risks to patients if mutations arise in critical genes, such as oncogenes [9].

In silico prediction tools are essential for nominating potential off-target sites during the guide RNA (gRNA) design phase. They are typically open-source online software that provides a convenient and efficient first pass for assessing off-target risk based primarily on sequence homology [16]. This guide focuses on three types of predictors: the versatile algorithm Cas-OFFinder, the user-friendly CCTop, and state-of-the-art deep learning models such as CCLMoff.

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the key differences between traditional tools (like Cas-OFFinder and CCTop) and newer deep learning models (like CCLMoff) for off-target prediction?

Traditional tools largely rely on sequence alignment and predefined rules about mismatch tolerance. In contrast, deep learning models can automatically learn complex sequence features and patterns from large, comprehensive datasets, often leading to superior performance and generalization [5] [28].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each tool type:

| Tool Type | Examples | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment-Based | Cas-OFFinder [16], CasOT | Exhaustive genome-wide scanning for sites with sequence similarity to the gRNA [16]. | Highly versatile; allows custom adjustment of PAM sequences, mismatch numbers, and bulges [16] [29]. |

| Scoring-Based | CCTop [29], MIT Score, CFD Score | Assigns weights/penalties based on mismatch position (e.g., proximity to PAM) and type to generate an off-target score [16] [29]. | Provides an intuitive user interface and ranks potential off-target sites, facilitating gRNA selection [29]. |

| Deep Learning-Based | CCLMoff [5], CRISPR-Net, Crispr-SGRU | Uses deep neural networks to automatically extract relevant features from gRNA and target site sequences [5] [28]. | Superior generalization to unseen gRNA sequences; captures complex, non-linear sequence relationships [5] [6]. |

| Di-O-demethylcurcumin | Di-O-demethylcurcumin, CAS:60831-46-1, MF:C19H16O6, MW:340.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Azido-PEG1-methyl ester | Azido-PEG1-methyl ester, CAS:1835759-80-2, MF:C6H11N3O3, MW:173.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

2. How do I choose the right prediction tool for my experiment?

The choice depends on your specific needs for accuracy, speed, and user support. The following table provides a comparative overview to aid in selection.

| Tool Name | Type | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas-OFFinder [30] [29] | Alignment-Based | No limit on mismatches; customizable PAM; fast searching [29]. | Researchers needing a flexible, first-pass scan of potential off-targets across a whole genome. |

| CCTop [29] | Scoring-Based | Intuitive interface; ranks off-targets by score; provides full output documentation [29]. | Beginners and experts seeking a user-friendly tool with clear candidate ranking for various editing applications. |

| CCLMoff [5] [6] | Deep Learning | Incorporates a pre-trained RNA language model; trained on 13 genome-wide detection datasets; high accuracy. | Projects requiring the highest prediction accuracy and robust performance on novel gRNA sequences, especially for therapeutic development. |

3. A deep learning model predicted a high-risk off-target site, but my validation experiment (e.g., GUIDE-seq) did not detect editing there. Why might this happen?

Discrepancies between in silico predictions and experimental results are common and can arise from several factors:

- Cellular Context: Deep learning models like CCLMoff are primarily trained on sequence data. They may not fully account for intracellular factors that influence Cas9 binding and cleavage, such as chromatin accessibility, epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA methylation, histone marks), and nuclear localization [16] [5]. A site that is accessible in silico might be buried in heterochromatin in a specific cell type.

- Training Data Bias: A model's performance is tied to the data it was trained on. If the model was not trained on data from a cell type or experimental condition similar to yours, its predictions may be less accurate [28].

- Sensitivity of Experimental Methods: Even highly sensitive methods like GUIDE-seq have limitations in detection efficiency and can be influenced by factors like transfection efficiency [16]. Very low-frequency off-target events might fall below the detection limit.

4. What should I do if different in silico tools give me conflicting off-target predictions?

Lack of consensus among predictors is a known challenge, as demonstrated in a study on Mucopolysaccharidosis type I where different tools identified vastly different numbers of off-target sites with low agreement [31]. To address this:

- Use a Consensus Approach: Rely on sites that are nominated by multiple, diverse tools (e.g., one alignment-based and one deep learning-based) [31].

- Prioritize by Score: Within each tool, pay closest attention to the top-ranked off-target sites with the highest predicted activity or lowest number of mismatches, particularly in the seed region near the PAM site [16] [31].

- Validate Experimentally: Treat all in silico predictions as a guide for targeted off-target validation. Use methods like GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq to experimentally confirm or refute the computationally predicted sites in your specific experimental system [16] [9].

## Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: The off-target site validated in my experiment was not predicted by any in silico tool.

- Potential Cause 1: Unaccounted for Bulges. Early prediction tools and some scoring models only consider mismatches and may not account for DNA or RNA bulges (insertions or deletions), which Cas9 can tolerate [5].

- Solution: Use tools that specifically include bulge prediction in their algorithm. When setting up your search, enable options for "bulges" or "indels." Cas-OFFinder, for instance, allows for the specification of bulge numbers [29].

- Potential Cause 2: Non-Canonical PAM Sequences. The tool may be restricted to the standard NGG PAM for SpCas9, while the nuclease might be interacting with a non-canonical PAM (e.g., NAG or NGA) [31].

- Solution: If using a tool that allows it (like Cas-OFFinder), expand the PAM search parameters to include other common non-canonical sequences [29].

- Potential Cause 3: Cell-Type Specific Genetic Variations. The reference genome used by the prediction tool might not contain a sequence variant present in your specific cell line, creating a novel off-target site [31].

- Solution: If available, use a personalized or population-specific genome reference for prediction. Always check known genetic variants in your cell line at the predicted off-target loci.

Problem: My chosen gRNA has high on-target efficiency but also many high-scoring off-target predictions.

- Potential Cause: The gRNA sequence has high homology to multiple genomic loci.

- Solution:

- Re-design gRNAs: Go back to your gRNA design tool (e.g., CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR) and select an alternative gRNA with a higher specificity score (e.g., a lower CFD off-target score) [9] [29].

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Switch from wild-type SpCas9 to a high-fidelity engineered variant (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) that has reduced tolerance for mismatches [9].

- Modify the gRNA: Truncating the gRNA length (to 17-18 nucleotides) or adding specific chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl analogs) can reduce off-target binding without completely abolishing on-target activity [9].

- Solution:

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and resources used in the field of CRISPR off-target prediction and analysis.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cas-OFFinder [30] [29] | A fast, versatile algorithm for exhaustive search of potential off-target sites with customizable parameters. | Initial genome-wide screening for sequences with homology to a candidate gRNA. |

| CCTop [29] | An online predictor that identifies and ranks candidate sgRNA target sequences based on their off-target score. | Rapidly identifying high-quality target sites for gene inactivation, HDR, and NHEJ experiments. |

| CCLMoff Model [5] [6] | A deep learning framework using an RNA language model for highly accurate and generalizable off-target prediction. | Selecting optimal sgRNAs with minimal off-target risk for preclinical therapeutic development. |

| GUIDE-seq [16] [9] | An experimental method that captures DSBs in cells by integrating double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODNs). | Unbiased, genome-wide experimental validation of predicted off-target sites in a relevant cell model. |

| CRISPOR [9] [29] | A web tool for gRNA design that ranks candidates using multiple on-target and off-target scoring algorithms. | Designing and selecting gRNAs, with comprehensive support from cloning to off-target analysis. |

| LPA1 receptor antagonist 1 | LPA1 receptor antagonist 1, MF:C28H26N4O4, MW:482.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Drim-7-ene-11,12-diol acetonide | Drim-7-ene-11,12-diol acetonide, MF:C18H30O2, MW:278.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

## Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Off-Target Assessment

The following diagram illustrates a robust, multi-step protocol integrating in silico prediction with experimental validation, forming a core methodology for detecting off-target effects in gene editing research.

## Decision Framework for Tool Selection

Use the workflow below to select the most appropriate prediction tool based on your project's specific requirements and stage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary advantages of using in vitro biochemical methods like CIRCLE-seq over cell-based methods for off-target nomination?

In vitro biochemical methods offer several key advantages for initial, genome-wide off-target discovery. They provide ultra-high sensitivity and can identify a broader spectrum of potential off-target sites because they are not limited by cellular delivery efficiency, chromatin states, or cell fitness effects [32] [11]. By using purified genomic DNA and high concentrations of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP), these methods can reveal rare cleavage events that might be missed in cell populations [32]. This makes them excellent for comprehensive, unbiased screening during the early sgRNA selection and risk assessment phase [11].

2. A common critique is that biochemical assays may overestimate biologically relevant off-target effects. How can I validate my findings?

While biochemical methods are highly sensitive for nominating off-target sites, their findings should be interpreted as a list of potential off-targets. It is recommended to validate bona fide off-target sites using complementary, cell-based methods [11]. Techniques like GUIDE-seq or amplicon sequencing can confirm whether the nominated sites are actually cleaved and edited in a cellular context, which accounts for factors like chromatin accessibility and DNA repair [32] [16] [11]. This two-tiered approach—broad discovery with a biochemical method followed by validation in a biologically relevant system—is considered a robust strategy for off-target assessment [11].

3. I have a limited amount of genomic DNA. Which method is most suitable?

CIRCLE-seq and CHANGE-seq are highly sensitive methods that require only nanogram amounts of purified genomic DNA, making them suitable for situations where DNA is scarce [11]. In contrast, Digenome-seq typically requires microgram quantities of input DNA [11] [12].

4. What is the key technological improvement of CHANGE-seq over CIRCLE-seq?

CHANGE-seq is described as an improved version of CIRCLE-seq that incorporates a tagmentation-based library prep process [11]. This enhancement reduces bias and improves the sensitivity of the assay, allowing for the detection of even rarer off-target events while also simplifying and streamlining the workflow [11].

Comparison of Key Biochemical Off-Target Detection Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of CIRCLE-seq, Digenome-seq, and CHANGE-seq to help you select the most appropriate method for your research needs.

Table 1: Summary of Biochemical Off-Target Assays

| Feature | Digenome-seq [11] [12] | CIRCLE-seq [32] [11] | CHANGE-seq [11] |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Description | Treats purified genomic DNA with nuclease, then detects cleavage sites by whole-genome sequencing. | Uses circularized genomic DNA and exonuclease digestion to enrich for nuclease-induced breaks. | Improved version of CIRCLE-seq with tagmentation-based library prep. |

| Sensitivity | Moderate; requires deep sequencing to detect off-targets. | High sensitivity; lower sequencing depth needed compared to Digenome-seq. | Very high sensitivity; can detect rare off-targets with reduced false negatives. |

| Input DNA | Micrograms of purified genomic DNA. | Nanogram amounts of purified genomic DNA. | Nanogram amounts of purified genomic DNA. |

| Key Enrichment Step | None (direct WGS of digested DNA). | Circularization of DNA → exonuclease removes linear DNA, enriching cleavage products. | DNA circularization + tagmentation → efficient capture of nuclease cuts. |

| Sequencing Depth | High (~400-500 million reads for human genome) [32] [12]. | Lower (~100-fold fewer reads than Digenome-seq) [32]. | High sensitivity with optimized sequencing. |

Experimental Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the core procedural steps for each method, highlighting the key differences in their approaches to enriching for nuclease-cleaved DNA fragments.

CIRCLE-seq Workflow

Digenome-seq Workflow

CHANGE-seq Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Biochemical Off-Target Detection Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Purified Genomic DNA | The substrate for in vitro cleavage. High-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA is essential [11] [12]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease (High Purity) | The active enzyme that creates double-strand breaks. Used as a purified protein to form the RNP complex [16] [12]. |

| In vitro Transcribed or Synthetic sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 nuclease to its target and potential off-target sequences [16]. |

| DNA Circularization Enzymes | Critical for CIRCLE-seq and CHANGE-seq. Enzymes like circligases are used to form covalently closed DNA circles [32] [11]. |

| Exonucleases | Used in CIRCLE-seq to degrade linear DNA fragments, thereby enriching for circularized DNA that was linearized by Cas9 cleavage [32] [11]. |

| Tagmentation Enzyme Mix | A key reagent for CHANGE-seq, which combines fragmentation and adapter ligation into a single step, streamlining library preparation [11]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Library Prep Kit | Required for preparing the enriched DNA fragments for high-throughput sequencing on platforms like Illumina [32] [11]. |

This technical support guide details the use of three key cellular methods—GUIDE-seq, DISCOVER-seq, and BLESS—for detecting off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. These techniques are essential for identifying biologically relevant off-target activity in living cells or native tissue contexts, capturing the influence of chromatin structure, DNA repair pathways, and cellular environment on editing outcomes. This resource provides troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols to support researchers and drug development professionals in ensuring the safety and specificity of gene editing therapies [11].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each method for easy comparison.

| Method | General Description & Principle | Input Material | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Primary Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GUIDE-seq [11] [33] | Incorporates a double-stranded oligonucleotide tag into double-strand breaks (DSBs) in vivo, followed by enrichment and sequencing. | Cellular DNA from edited, tagged cells. [11] | High sensitivity for off-target DSB detection; reflects true cellular activity. [11] | Requires efficient delivery of oligonucleotide tag; may miss rare sites. [11] | DSBs via tag integration [11] |

| DISCOVER-seq+ [34] | Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of the DNA repair protein MRE11 recruited to CRISPR-Cas-targeted sites. Often combined with DNA-PKcs inhibition (DISCOVER-Seq+) to boost signal. | Cellular DNA; ChIP-seq of MRE11 binding. [11] | High sensitivity in native chromatin; suitable for in vivo and primary cells; captures real nuclease activity. [11] [34] | Technically complex (ChIP protocol); requires specific antibodies. [11] | DSBs via MRE11 binding [11] [34] |

| BLESS [11] [4] | Direct in situ labeling of DSB ends in fixed cells with biotinylated linkers, followed by capture and sequencing. | Fixed/permeabilized cells or nuclei. [11] | Preserves genome architecture; captures breaks in situ. [11] | Technically complex; lower throughput; variable sensitivity. [11] | DSBs via direct end-labeling [11] [4] |

Experimental Protocols

GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing)

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Transfection: Co-deliver into living cells the Cas9 nuclease (as plasmid, mRNA, or ribonucleoprotein complex) and sgRNA, along with the proprietary double-stranded GUIDE-seq oligonucleotide tag [11].

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 2-3 days post-transfection and isolate genomic DNA using standard methods.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Fragment the DNA and perform next-generation sequencing (NGS) library preparation. The tag-containing fragments are enriched, amplified, and sequenced [11].

- Data Analysis: Process sequencing reads through a bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., the original GUIDE-seq algorithm) to map the genomic locations of tag integration, which correspond to both on-target and off-target DSBs [11] [33].

DISCOVER-seq+ (Discovery ofin situCas Off-targets with Verification and Sequencing)

Detailed Methodology:

- Gene Editing & Inhibition: Deliver CRISPR-Cas9 components into target cells or in vivo. To enhance sensitivity (DISCOVER-Seq+), inhibit DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) using compounds like Ku-60648 or Nu7026 to accumulate MRE11 at break sites [34].

- Cell Fixation and Cross-linking: Fix cells to preserve protein-DNA interactions.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): Lyse cells, shear chromatin, and immunoprecipitate DNA fragments bound to MRE11 using a specific anti-MRE11 antibody [11] [34].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Reverse cross-links, purify the enriched DNA, and construct an NGS library for sequencing [34].

- Data Analysis: Analyze sequencing data with a dedicated pipeline (e.g., BLENDER) to identify significant peaks of MRE11 binding, which indicate Cas9 cleavage sites genome-wide [34].

BLESS (Breaks Labeling, Enrichment on Streptavidin, and Sequencing)

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells or nuclei promptly to "freeze" DSBs in their native genomic context and permeabilize them to allow reagent access [4].

- In Situ Breaks Labeling: In fixed and permeabilized cells, label the ends of DSBs using biotinylated linkers or adapters [11] [4].

- Genomic DNA Extraction & Enrichment: Extract genomic DNA and capture the biotin-labeled fragments containing DSBs using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads [4].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Process the enriched DNA fragments into an NGS library and sequence [11] [4].

- Data Analysis: Map the sequenced reads back to the reference genome to identify the precise locations of DSBs [4].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

GUIDE-seq

FAQ: Why is my GUIDE-seq oligonucleotide not being efficiently incorporated?

- A: Low tag incorporation is a common issue. Ensure the oligonucleotide is delivered at an optimal concentration. Using electroporation for delivery (especially in hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells or stem cells) can significantly improve efficiency compared to lipid-based methods. Test different delivery conditions and tag concentrations.

FAQ: The experiment identified a very high number of off-target sites. Is this normal?

- A: GUIDE-seq is highly sensitive. However, an unusually high number may indicate that the sgRNA has low specificity. Verify your sgRNA design using multiple in silico prediction tools (e.g., CRISPOR) to select guides with minimal predicted off-targets. Consider testing a high-fidelity Cas9 variant to reduce off-target cleavage [9].

DISCOVER-seq

FAQ: How does DNA-PKcs inhibition improve DISCOVER-Seq+ sensitivity?

- A: Inhibiting DNA-PKcs blocks the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway. This causes a buildup of the MRE11 repair complex at the DSB sites, prolonging its residence time and thereby increasing the signal captured during ChIP-seq, which can discover up to fivefold more off-target sites [34].

FAQ: What is the recommended control for DISCOVER-seq experiments?

- A: Always perform a control experiment under identical conditions (including inhibitor treatment) but without the Cas9 nuclease. This identifies background MRE11 binding signals unrelated to CRISPR editing. The final set of off-target sites is determined by subtracting sites found in the "no Cas9" control from those in the experimental sample [34].

BLESS

FAQ: The signal-to-noise ratio in my BLESS experiment is low. How can I improve it?

- A: Low signal can stem from inefficient in situ labeling or degradation of DNA ends. Ensure fixation is performed quickly after sampling to preserve break ends. Optimize the permeabilization and labeling reaction times and temperatures. Using fresh reagents and including positive control samples with known DSBs can help troubleshoot this issue [4].

FAQ: Can BLESS detect transient DSBs?

- A: Yes, a key advantage of BLESS is that it provides a "snapshot" of DSBs at the moment of fixation, making it suitable for detecting transient breaks. However, its sensitivity may be limited by the efficiency of the in situ labeling reaction [11] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for implementing these methods.

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Methods |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitor (e.g., Ku-60648) | Boosts MRE11 residence at DSBs by blocking NHEJ, enhancing ChIP-seq signal sensitivity [34]. | DISCOVER-seq+ |

| Anti-MRE11 Antibody | Specifically binds to MRE11 protein for chromatin immunoprecipitation of Cas9-targeted sites [11] [34]. | DISCOVER-seq |

| Biotinylated Linker / Adapter | Labels DSB ends in situ for subsequent capture and enrichment [11] [4]. | BLESS |

| Double-stranded Oligonucleotide Tag | Integrates into DSBs, serving as a molecular barcode for PCR amplification and sequencing of break sites [11]. | GUIDE-seq |

| Streptavidin Magnetic Beads | Captures and enriches biotin-labeled DNA fragments containing DSBs [4]. | BLESS |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variant | Engineered nuclease with reduced off-target activity; a critical negative control or tool to mitigate risk [9]. | All (as control) |

Method Workflow Diagrams

GUIDE-seq Workflow

DISCOVER-seq+ Workflow

BLESS Workflow

The application of CRISPR-Cas9 and other genome editing tools has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development. However, a significant challenge remains the occurrence of off-target effects—unintended modifications at sites other than the intended on-target location [16] [35]. These off-target events can confound experimental results and raise substantial safety concerns for clinical applications [36]. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has emerged as the gold-standard method for comprehensively identifying and quantifying these unintended edits, providing the precision and sensitivity required for confident off-target assessment [37]. Two primary NGS approaches are employed: Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Targeted Amplicon Sequencing. This guide details their applications, provides troubleshooting support, and outlines best practices for their implementation in gene editing research.

Core Technology Comparison: WGS vs. Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

The choice between WGS and Targeted Amplicon Sequencing is fundamental and depends on the research objective, scale, and available resources. The table below summarizes their key characteristics for off-target detection.

Table 1: Comparison of WGS and Targeted Amplicon Sequencing for Off-Target Analysis

| Feature | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Targeted Amplicon Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Coverage Scope | Unbiased, comprehensive profiling of the entire genome [38] [37] | Focused analysis of specific, pre-identified regions of interest [38] [37] |

| Primary Application in Off-Target Detection | Unbiased discovery and nomination of novel off-target sites ("hotspots") across the genome [37] | Targeted verification and quantification of editing efficiency at known on-target and nominated off-target sites [37] |

| Cost & Resource Requirements | Higher cost and computational complexity [38] [39] | Highly cost-effective for targeted studies [38] |

| Typical Turnaround Time | Longer (e.g., 5-7 weeks reported by service providers) [39] | Shorter (e.g., 3-4 weeks reported by service providers) [38] [39] |

| Ideal Use Case | Initial, unbiased discovery phase to find where off-target edits might occur [37] | Validation and routine monitoring phase to quantify how often editing occurs at known sites [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Off-Target Detection

A robust off-target analysis strategy often involves a two-phase approach: an initial genome-wide discovery step followed by targeted validation and quantification [37] [27].

Genome-Wide Discovery Methods for Off-Target Nomination

Before you can quantify off-target effects, you must first identify where in the genome they might occur. The following methods are used to nominate these "hotspot" sites.

Table 2: Empirical Methods for Genome-Wide Off-Target Site Discovery

| Method | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| GUIDE-seq [37] [27] | Integrates double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODNs) into DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in cells, followed by sequencing. | Highly sensitive, cost-effective, and has a low false-positive rate [16] [37]. | Limited by transfection efficiency [16]. |

| CIRCLE-seq [37] [27] | An in vitro method that circularizes sheared genomic DNA, incubates it with Cas9/sgRNA, and sequences linearized DNA fragments. | Extremely high sensitivity; performed in a test tube without cell culture [16] [37]. | An in vitro method that may not fully reflect cellular context [16]. |

| DISCOVER-seq [37] [27] | Utilizes the DNA repair protein MRE11 to mark DSB sites for chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (ChIP-seq) in vivo. | Unbiased detection in vivo; uses endogenous repair machinery [37]. | Potential for false positives [16]. |