The Ti Plasmid's T-DNA Borders: From Plant Transformation Engine to Advanced Biomedical Tool

This comprehensive review explores the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and its T-DNA border sequences, detailing their foundational biology and their pivotal evolution into sophisticated genetic engineering vectors.

The Ti Plasmid's T-DNA Borders: From Plant Transformation Engine to Advanced Biomedical Tool

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and its T-DNA border sequences, detailing their foundational biology and their pivotal evolution into sophisticated genetic engineering vectors. We examine the core mechanisms of T-DNA excision and transfer, establish current best practices for vector design and transformation protocols across diverse systems, and address common challenges in efficiency and specificity. The article provides a critical comparative analysis of T-DNA border systems against modern genome-editing tools and non-Agrobacterium delivery methods, emphasizing validation strategies for stable integration and expression. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights the enduring relevance of this natural genetic engineer in basic research, biomanufacturing, and emerging therapeutic applications.

Deconstructing the Ti Plasmid: Nature's Genetic Engineer and the Gateway of T-DNA Borders

This whitepaper details the molecular machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a paradigm for interkingdom gene transfer. The discussion is framed within an ongoing thesis investigating the precise regulatory mechanisms of the Ti (Tumor-inducing) plasmid, with particular focus on the cis-acting T-DNA border sequences and their recognition by the VirD1/VirD2 endonuclease complex. Understanding these elements is critical for advancing plant biotechnology and therapeutic protein production.

Molecular Pathogenesis: The Ti Plasmid and Virulence System

Agrobacterium pathogenicity is encoded by its ~200 kbp Ti plasmid, which contains two essential regions: the T-DNA (Transferred-DNA) and the vir (virulence) region. The vir region is organized into operons (virA, virB, virC, virD, virE, virG, virH), induced by plant-derived phenolic compounds (e.g., acetosyringone) and sugars.

Table 1: Core Components of the Ti Plasmid Virulence System

| Component | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| VirA/VirG | Two-component signal transduction system; VirA senses host signals, phosphorylates VirG. | VirG-P activates transcription of other vir operons. |

| VirD1/VirD2 | Endonuclease complex; VirD2 nicks T-DNA border sequences. | VirD2 remains covalently attached to the 5' end of the T-strand (pilot protein). |

| T-DNA Borders | 25-bp direct repeat sequences flanking the T-DNA. | Right border (RB) is essential; left border (LB) enhances efficiency. |

| VirB1-VirB11, VirD4 | Type IV Secretion System (T4SS). Forms a pilus and channel for T-strand/complex transfer. | 11 components; ATP-dependent. |

| VirE2 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein. Coats the T-strand in the plant cytoplasm. | Protects T-strand from nucleases, guides to nucleus. |

| VirE3, VirF | Effector proteins transferred into host cell. | VirE3 interacts with plant importin-α; VirF targets host proteins for proteasomal degradation. |

Signaling Pathway: From Plant Signal tovirGene Induction

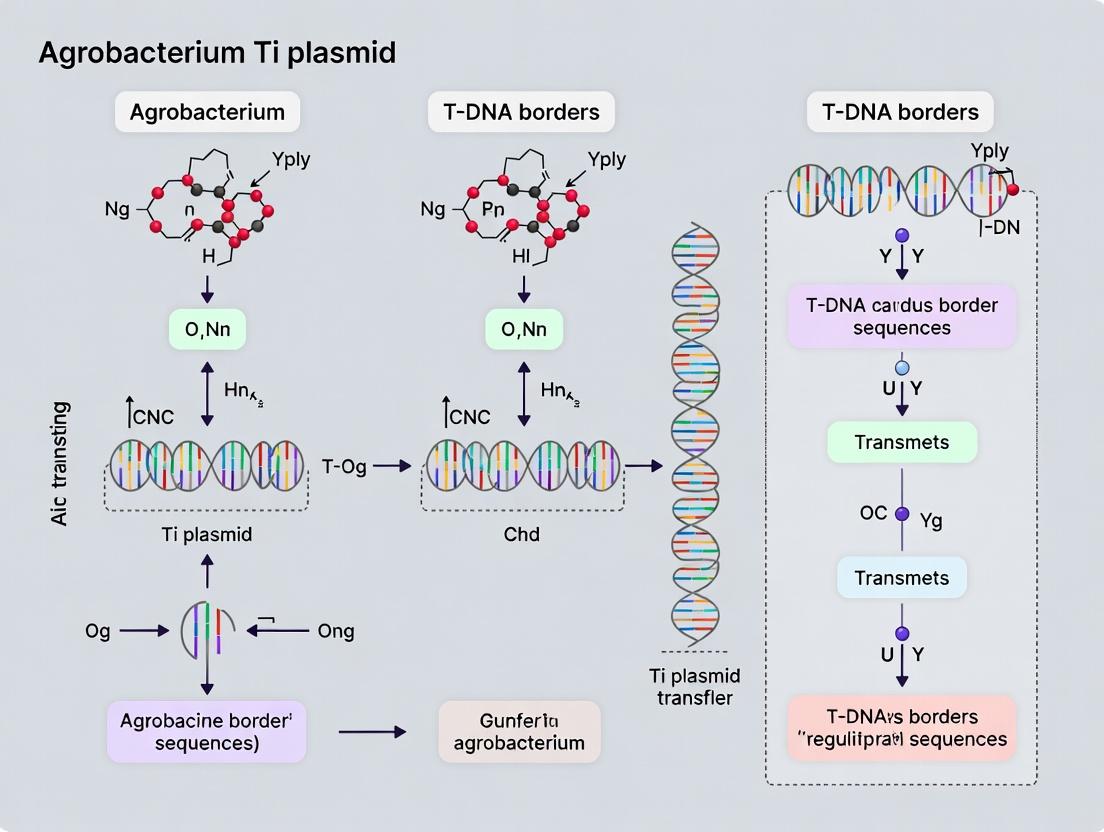

Diagram 1: vir gene induction signaling pathway.

T-DNA Processing and Transfer: A Detailed Workflow

Protocol 4.1: In Vitro T-DNA Border Nicking Assay

- Purpose: To demonstrate VirD1/VirD2 endonuclease activity on T-DNA border sequences.

- Materials: Purified VirD1 and VirD2 proteins, supercoiled plasmid DNA containing a T-DNA border sequence, reaction buffer (Tris-HCl, MgCl₂, DTT, ATP), stop solution (EDTA, SDS), agarose gel electrophoresis equipment.

- Method:

- Prepare a 50 µL reaction mix containing 1x buffer, 0.5 µg plasmid DNA, 100 ng VirD1, 200 ng VirD2.

- Incubate at 28°C for 30 minutes.

- Stop reaction with 5 µL of 0.5 M EDTA/2% SDS.

- Analyze products by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. A nicked circular (relaxed) form will migrate slower than supercoiled DNA.

Diagram 2: T-DNA processing and transfer workflow.

Research Reagent Solutions: The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ti Plasmid/T-DNA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic inducer of the vir gene region. Used to activate Agrobacterium for plant transformation. | Typically used at 100-200 µM in co-cultivation media. |

| Binary Vector System | Engineered plasmids separating T-DNA (on small vector) from vir genes (on helper plasmid). | pBIN19, pGreen; enables cloning genes of interest into T-DNA. |

| Disarmed Ti Plasmid | Ti plasmid with oncogenes removed from T-DNA ("disarmed"), used as a helper. | pTiBo542ΔT-DNA (super-virulent strain AGL1 background). |

| Border Sequence Oligos | Synthetic oligonucleotides matching 25-bp RB/LB for binding/activity studies. | Critical for in vitro nicking assays and vector construction. |

| Anti-VirD2 Antibody | Detects VirD2 protein or the T-strand/VirD2 complex (immunoprecipitation, Western blot). | Monoclonal antibodies allow quantitative analysis. |

| *virG Constitutive Mutant | Strain with always-active VirG (e.g., virG(N54D)), inducing vir genes without plant signals. | Strain A281 (for super-transformation). |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Supports co-cultivation and regeneration of transformed plant cells. | MS (Murashige and Skoog) media with specific hormones. |

Current Research Frontiers and Quantitative Data

Recent research focuses on the structural biology of the T4SS, enhancing transformation efficiency in recalcitrant crops, and repurposing the system for mammalian cell gene delivery (e.g., "T-DNA" delivery to human cells).

Table 3: Quantitative Data on T-DNA Transfer and Transformation

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Context/Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| T-DNA Size Limit | Up to ~150 kbp | Using Binary-BAC (BIBAC) vectors. |

| Optimal Acetosyringone Concentration | 100 - 200 µM | For vir induction in standard lab strains (e.g., LBA4404). |

| Co-cultivation Time | 48 - 72 hours | For Arabidopsis thaliana floral dip or leaf disc assays. |

| Transformation Frequency (Model Plants) | 70-90% of explants | Arabidopsis floral dip, producing T1 seeds. |

| Number of T-DNA Integrants | 1 - 5 copies per genome | Common range in stable transformants (species-dependent). |

| T-strand Production Onset | 4 - 16 hours post vir induction | Detectable by PCR or Southern blot. |

Within the broader thesis on Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and T-DNA border sequences, this whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the plasmid's core functional regions. The Ti plasmid is the molecular engine of crown gall disease, engineered for plant transformation. Its anatomy is defined by three critical sectors: the T-DNA region transferred to the plant genome, the virulence (vir) region governing transfer machinery, and the opine catabolism region ensuring a unique ecological niche. Understanding this structure is fundamental to refining T-DNA delivery precision for biotechnology and therapeutic applications.

The Virulence (Vir) Region: A Molecular Regulatory Hub

The ~30 kb vir region, typically organized into seven major operons (virA, virB, virC, virD, virE, virG, virH), is induced by plant phenolic signals (e.g., acetosyringone) and acidic pH.

Key Regulatory and Structural Components

| Gene/Operon | Function | Protein Product Role |

|---|---|---|

| virA | Environmental sensor | Membrane-bound histidine kinase; senses phenolics/sugars, autophosphorylates. |

| virG | Transcriptional regulator | Response regulator; phosphorylated by VirA, activates transcription of other vir operons. |

| virB1-B11 | Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) | Forms the pilus and transmembrane channel for T-DNA/protein transfer. VirB2 is the major pilin subunit. VirD4 is the coupling protein. |

| virD1/D2 | T-DNA processing | Endonuclease complex; nicks T-DNA border sequences. VirD2 remains covalently attached to the 5' end of the single-stranded T-DNA (T-strand). |

| virE2 | T-strand protection & nuclear targeting | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein; coats T-strand in plant cytoplasm, aids nuclear import. VirE1 acts as a chaperone for VirE2. |

| virC1 | Enhances T-DNA processing | Binds to "overdrive" sequences, enhancing VirD-mediated nicking at border sequences. |

| virH/virF | Host modulation (pTi-specific) | virH (pTiC58): P450 enzymes modify plant compounds. virF (pTiBo542): involved in host protein degradation. |

Experimental Protocol:VirGene Induction Assay

Objective: To quantify vir gene induction in response to plant signal molecules. Methodology:

- Culture Preparation: Grow A. tumefaciens strain (e.g., A348) to mid-log phase in minimal medium.

- Induction: Add acetosyringone (AS) to final concentration of 100 µM. Use a control without AS.

- Sampling: Collect 1 mL aliquots at 0, 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours post-induction.

- β-Galactosidase Assay (for vir::lacZ fusions):

- Pellet cells, resuspend in Z-buffer.

- Add toluene, vortex to permeabilize cells.

- Add ONPG (o-Nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) substrate, incubate at 28°C.

- Stop reaction with Na₂CO₃, measure absorbance at 420 nm.

- Calculate Miller Units: (1000 * A420) / (time (min) * volume (mL) * A600).

- RT-qPCR (Alternative): Extract RNA, synthesize cDNA, perform qPCR with primers for virB2 or virE2, normalize to recA.

Diagram 1: Vir region induction signaling pathway.

Opine Catabolism: The Ti Plasmid's Ecological Driver

Opines are novel amino acid-sugar conjugates synthesized in the transformed plant by enzymes encoded on the T-DNA. The Ti plasmid carries catabolic genes for the specific opine(s) its T-DNA produces.

Opine Types and Catabolic Gene Organization

| Ti Plasmid Type | Opine Synthesized | Catabolic Genes | Regulator | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octopine-type | Octopine, Mannopine | occ or moc | OccR | Uptake and breakdown of opines as carbon/nitrogen source. |

| Nopaline-type | Nopaline, Agrocinopine | noc | NocR | Uptake and breakdown of opines. |

| Agropine-type | Agropine, Mannopine | agr | AgrR | Uptake and breakdown of opines. |

Experimental Protocol: Opine Catabolism Screen

Objective: To identify Ti plasmid type based on bacterial utilization of specific opines. Methodology:

- Plate Preparation: Prepare minimal agar plates lacking a carbon source. Spread filter-sterilized opine solution (e.g., octopine, nopaline; 1-5 mM) onto the surface.

- Strain Streaking: Streak Agrobacterium test strains and positive/negative control strains.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at 28°C for 3-5 days.

- Analysis: Growth indicates functional opine catabolism genes. Confirm by HPLC-MS of culture supernatants to show opine depletion.

Transfer-DNA (T-DNA): The Delivered Genetic Cargo

The T-DNA is defined by 25-bp direct repeat border sequences (Right Border, RB; Left Border, LB). The RB is critical for nicking and transfer initiation.

Core T-DNA Elements

| Element | Sequence (Consensus) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Right Border (RB) | 5'-TGGCAGGATATATTGGCGGGTAAAC-3' | virD1/D2 nicking site; transfer origin. Hyper-variable in the central "core" region. Essential for efficient T-DNA transfer. |

| Left Border (LB) | 5'-TGGCAGGATATATTGTGGTGTAAAC-3' | virD1/D2 nicking site; defines left terminus. Transfer is often polar, proceeding RB to LB. |

| Overdrive Sequence | 5'-TGTTTGTTTGCAATTGTGTAATGTAAT-3' | Enhancer element located adjacent to RB; binds VirC1 to stimulate nicking. |

| Oncogenes | iaaM, iaaH, ipt | Auxin & cytokinin biosynthesis genes; cause plant tumorigenesis ("disarmed" in vectors). |

| Opine Synthase | nos (nopaline), ocs (octopine) | Gene for opine production in plant tumor. |

Experimental Protocol: T-DNA Border Nicking Assay

Objective: To demonstrate virD-mediated site-specific nicking at T-DNA borders. Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Clone a T-DNA border sequence (e.g., RB) into a plasmid. Label the border-containing fragment at the 5' end with [γ-³²P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase.

- Protein Incubation: Incubate the labeled DNA substrate with purified VirD1/VirD2 proteins (or vir-induced Agrobacterium cell extracts) in nicking buffer (pH 5.7, Mg²⁺ present) at 25°C for 30 min.

- Reaction Stop: Add EDTA and SDS to stop the reaction.

- Analysis: Denature samples, run on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. A virD-dependent nick converts the labeled, full-length strand into a shorter, labeled fragment detectable by autoradiography.

Diagram 2: T-DNA border recognition and processing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Acetosyringone (AS) | Phenolic inducer of vir genes. Critical for Agrobacterium virulence induction in lab assays and plant transformation. | 100 mM stock in DMSO or ethanol. Working concentration: 100-200 µM. |

| ONPG (o-Nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) | Colorimetric substrate for β-galactosidase (lacZ) reporter gene assays. Measures vir gene promoter activity. | 4 mg/mL in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). |

| Opine Standards | Analytical references for HPLC, TLC, or MS identification of opine types produced by transformed tissues or catabolized by bacteria. | Octopine, Nopaline, Agropine (commercially purified, >95%). |

| VirD2-Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of VirD2 protein bound to T-strands or in cellular localization studies. | Polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies raised against purified VirD2. |

| Border Sequence Oligonucleotides | Probes for Southern blotting or primers for PCR to verify T-DNA insertion and border integrity in transgenic lines. | 25-mer sequences matching RB/LB consensus, often with added restriction sites for cloning. |

| Disarmed Ti Vector (e.g., pGV3850) | Ti plasmid with oncogenes replaced by a conventional plasmid (e.g., pBR322). Allows cloning into T-DNA without causing tumors. | Contains intact vir region and T-DNA borders for gene transfer to plants. |

| Mini-Ti or Binary Vector (e.g., pBIN19) | Small E. coli/Agrobacterium* shuttle vector with T-DNA borders. Requires vir helper plasmid (pAL4404) in trans. | Standard for plant transformation; contains selectable marker (e.g., nptII) and MCS within T-DNA. |

| Agrobacterium Helper Strain | Strain carrying a Ti plasmid with a complete vir region but no T-DNA (disarmed) to provide vir functions in trans for binary vectors. | LBA4404 (pAL4404, octopine-type vir), EHA101 (pEHA101, super-virulent pTiBo542 vir), GV3101 (pMP90). |

Within the broader thesis on Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation, the T-DNA border sequences are the cis-acting elements that define the genetic cargo to be transferred from the bacterium to the plant cell nucleus. Flanking the T-DNA on the Ti (Tumor-inducing) or Ri (Root-inducing) plasmid, these imperfect 25-bp direct repeats are recognized and processed by the VirD1/VirD2 endonuclease complex. The precise cleavage at these borders initiates the production of the single-stranded T-strand, the actual molecule transferred. This review provides an in-depth technical analysis of these critical sequences, their variations, and their experimental manipulation.

Structural and Sequence Analysis of Border Sequences

The consensus border sequence is based on the canonical nopaline-type Ti plasmid sequence. Variations exist across different Agrobacterium strains and engineered binary vectors, influencing efficiency and directionality.

Table 1: Consensus and Variant T-DNA Border Sequences

| Border Type | Sequence (5' → 3') | Key Features | Cleavage Efficiency (%)* | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Border (RB) Consensus | 5'-TGGCAGGATATATTGTCGCTGTAAAC-3' | Highly conserved "core" (bold), complete repeat. | ~100 (Reference) | Essential for initiation; overdrive sequences enhance. |

| Left Border (LB) Consensus | 5'-TGGCAGGATATATTGTCGCTGTAAAC-3' | Often degenerate; "core" sequence less conserved. | 10-60 | Lower efficiency reduces vector backbone transfer. |

| Superbinary Vector RB | As consensus + 5' overdrive | Augmented with virG from pTiBo542. | 120-150 | Enhances T-strand production in recalcitrant plants. |

| Engineered LB (pORE) | Modified repeats | Multiple LB-like sequences in reverse orientation. | <5 | Designed to minimize read-through and backbone transfer. |

| Octopine-type LB | 5'-TGGCAGGATATATCGCGTGTAAACT-3' | 3 bp differences from nopaline consensus. | ~40 | Strain-specific variations. |

*Relative efficiency compared to standard nopaline RB under identical experimental conditions.

Molecular Mechanism: From Border Recognition to T-Strand Export

The process is initiated by the induction of the vir region by plant phenolic signals.

Critical Experimental Protocols

Protocol:In VitroBorder Cleavage Assay

Purpose: To verify the functionality of a given border sequence and the activity of purified VirD1/VirD2 proteins. Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit. Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Clone the border sequence to be tested (~50-100 bp surrounding the core) into a standard plasmid (e.g., pUC19). Purify supercoiled plasmid DNA.

- Protein Purification: Express and purify His-tagged VirD1 and VirD2 proteins from E. coli.

- Reaction Setup:

- Combine in a 20 µL reaction: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM DTT, 100 ng plasmid substrate, 50 ng VirD1, 100 ng VirD2.

- Incubate at 28°C for 30 minutes.

- Analysis: Stop reaction with 0.1% SDS. Analyze products by:

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (1%): Cleavage converts supercoiled to nicked/open circular forms.

- Denaturing PAGE: For detecting single-stranded cleavage products using radiolabeled substrates.

Protocol: Assessing T-DNA Transfer Efficiency Using GUS Intron Assay

Purpose: Quantitatively compare the transfer efficiency mediated by different border sequence constructs. Methodology:

- Vector Construction: Insert the gene of interest (e.g., GUS with a plant intron) between the border variants to be tested in a binary vector.

- Agrobacterium Strain Transformation: Electroporate the constructs into a disarmed Agrobacterium strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101).

- Plant Inoculation: Co-cultivate Agrobacterium with explants (e.g., tobacco leaf discs, Arabidopsis seedlings) for 48h.

- Selection & Histochemistry: Transfer explants to selection media. After 2-3 days, stain tissues for GUS activity (X-Gluc substrate, 37°C, overnight). Fix in ethanol.

- Quantification: Count blue foci per explant under a dissecting microscope. Use ≥30 explants per construct. Perform statistical analysis (ANOVA).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for T-DNA Border Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector Kit | Modular plasmids with multiple cloning sites flanked by standardized borders (e.g., pCAMBIA, pGreen). | pCAMBIA1301 (CAMBIA) |

| Superbinary Vector | Contains additional virG and virB genes from pTiBo542 for enhanced virulence. | pSB1 (Japan Tobacco) |

| Disarmed Agrobacterium Strain | Ti plasmid with oncogenes removed but vir region intact (e.g., LBA4404, EHA105). | LBA4404 (Thermo Fisher) |

| VirD1/VirD2 Recombinant Proteins | Purified proteins for in vitro nicking assays. | Custom expression (e.g., Agrisera) |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound used to induce the vir regulon in vitro. | D134406 (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| X-Gluc (5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronic acid) | Substrate for histochemical detection of β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity. | 042917-10MG (GoldBio) |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Specific basal media for co-cultivation and selection (e.g., MS, B5). | Murashige & Skoog Basal Salt Mixture (PhytoTech) |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | For accurate amplification of border sequences for cloning. | Q5 High-Fidelity (NEB) |

| Methylation-Insensitive Restriction Enzymes | For analyzing border cleavage products, unaffected by Dam/Dcm methylation. | EcoRI-HF, PstI-HF (NEB) |

Advanced Applications and Current Research Directions

Current research within the thesis framework focuses on:

- Precision Engineering: Using synthetic biology to design "ultra-clean" borders that eliminate transfer of vector backbone sequences, crucial for compliant commercial GMO development.

- Dual Border Systems: Investigating asymmetric border pairs to control the direction and copy number of integration.

- Non-Plant Transformations: Exploiting the T-DNA system for targeted DNA delivery in fungi, human cells (e.g., for CAR-T therapy), and other eukaryotes, requiring optimization of border recognition.

- Crystal Structures: Recent efforts in solving the VirD2-border DNA complex structure provide atomic-level insights for rational design.

Thesis Context: This whitepaper provides a technical dissection of the core molecular machinery driving T-DNA processing and transfer, a central component of broader research into Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid engineering, border sequence specificity, and its applications in plant biotechnology and therapeutic development.

The transfer of T-DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to plant cells is mediated by the vir region of the Ti plasmid. This process involves a sophisticated series of protein-DNA interactions for border recognition, T-strand excision, and conjugative transfer. Understanding this mechanism is pivotal for optimizing plant transformation and developing novel DNA delivery tools for gene therapy and drug discovery.

Core Molecular Machinery

Vir Protein Complexes and Functions

The key proteins involved in T-DNA processing are encoded by the virD operon.

Table 1: Core Vir Proteins in T-DNA Processing

| Protein | Function | Key Domains/Features |

|---|---|---|

| VirD1 | Topoisomerase I-like activity; assists VirD2 in border recognition and nicking. | Single-stranded DNA binding, facilitates complex assembly. |

| VirD2 | Site-specific endonuclease; nicks the bottom strand at the border sequences. Covalently attaches to the 5' end of the T-strand (pilot protein). | Tyrosine residue (Tyr-29) for covalent linkage, nuclear localization signals (NLS) for plant nuclear import. |

| VirC1 | Binds to the "overdrive" sequence near borders; enhances T-strand production. | ATPase activity, promotes relaxosome assembly. |

| VirC2 | Supports VirC1 function; precise role under investigation. | Often co-purified with VirC1. |

| VirE2 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein; coats the T-strand in the plant cytoplasm for protection and import. | Cooperative binding, NLS motifs. |

| VirE1 | Chaperone for VirE2; prevents VirE2 aggregation in bacterial cell. | Required for secretion of VirE2. |

Quantitative Parameters of T-DNA Transfer

Table 2: Key Quantitative Data on T-DNA Borders and Processing

| Parameter | Typical Value/Sequence | Experimental Notes & Variation |

|---|---|---|

| Conserved Border Sequence | 5'-TGGCAGGATATATTGTNCACAA-3' (LB) | Nick site is between the 3rd and 4th base of the conserved 12-13bp core (underlined). |

| Nick Site (Bottom Strand) | CATG | Precisely between the T and G of the core sequence. |

| Border Repeat Length | ~25 bp | Imperfect repeats; right border (RB) is more precise and critical. |

| Overdrive Sequence | 5'-TGTTTGTTTGAAGGGATCGCAATGTATAT-3' | ~50 bp from RB; enhances excision efficiency up to 1000-fold. |

| T-Strand Production Rate | ~1 T-strand per cell per hour (induced conditions) | Measured via quantitative PCR in vir-induced cultures. |

| VirD2 Relaxase Turnover | ~1 nick per minute in vitro | Highly dependent on VirD1 presence and Mg²⁺ concentration. |

Stepwise Mechanism and Experimental Analysis

Recognition and Excision: The Relaxosome Complex

Detailed Protocol 1: In Vitro Nicking Assay to Map Border Cleavage Objective: To demonstrate VirD1/VirD2-dependent site-specific nicking at T-DNA borders. Materials: Supercoiled plasmid containing a T-DNA border, purified His-tagged VirD1 and VirD2 proteins, reaction buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl₂, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT), 0.5 M EDTA, proteinase K, agarose gel equipment. Procedure:

- Set up a 50 µL reaction with 500 ng of supercoiled plasmid DNA, 100 nM VirD1, and 50 nM VirD2 in reaction buffer.

- Incubate at 30°C for 30 minutes.

- Stop the reaction by adding EDTA to 25 mM and Proteinase K to 0.5 mg/mL. Incubate at 37°C for 15 min.

- Analyze products by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. A successful nicking reaction converts supercoiled (Form I) to nicked open-circle (Form II) DNA, detectable by gel shift.

- For precise mapping, use a 5'-end radiolabeled oligonucleotide spanning the border in a similar reaction. Resolve products on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel to identify the exact cleavage site.

Diagram 1: T-DNA Recognition, Excision, and Transfer Pathway

Transfer and Cytoplasmic Trafficking

Following excision, the VirD2-T-strand complex is exported through a Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) encoded by virB operon and virD4. In the plant cell, VirE2 is independently exported and coats the T-strand.

Detailed Protocol 2: Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) for Vir Protein-Protein Interactions Objective: To confirm interaction between VirD2 and T4SS coupling protein VirD4. Materials: A. tumefaciens strain expressing FLAG-tagged VirD4 and HA-tagged VirD2, anti-FLAG agarose beads, lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors), wash buffer, SDS-PAGE and Western blot apparatus, anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. Procedure:

- Grow Agrobacterium culture under vir-inducing conditions (+200 µM acetosyringone).

- Harvest cells, lyse in ice-cold lysis buffer.

- Incubate clarified lysate with anti-FLAG agarose beads for 2h at 4°C.

- Wash beads 5x with wash buffer.

- Elute bound proteins with 2x SDS sample buffer.

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting: probe membrane sequentially with anti-HA (to detect co-precipitated VirD2) and anti-FLAG (to confirm VirD4 pull-down).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying T-DNA Processing

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Supplier / Cat. No. (Illustrative) |

|---|---|---|

| Supercoiled Ti Plasmid or Border-Containing Vector | Substrate for in vitro nicking assays and excision studies. | Lab-constructed; e.g., pTiC58 (ATCC 37349). |

| Purified Recombinant VirD1 & VirD2 Proteins | Core enzymes for biochemical characterization of border cleavage. | Expressed from pET vectors in E. coli, purified via His-tag. |

| Acetosyringone (3',5'-Dimethoxy-4'-hydroxyacetophenone) | Phenolic inducer of the vir regulon for in vivo studies. | Sigma-Aldrich, D134406. |

| Vir-Specific Antibodies (α-VirD2, α-VirE2) | Detection of protein expression, localization (microscopy), and interaction assays. | Custom from genomic labs; available from Agrisera. |

| Border Sequence Oligonucleotides (FAM/Radio-labeled) | Probes for EMSA or substrates for high-resolution nicking site mapping. | Custom synthesis from IDT or Eurofins. |

| Type IV Secretion Inhibitors (e.g., CCF4 peptide) | To dissect export step from excision in transfer assays. | Tocris Bioscience (various). |

| Plant Suspension Cells (e.g., Nicotiana tabacum BY-2) | Recipient cells for quantitative T-DNA transfer frequency assays. | Common lab cell lines. |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflows for T-DNA Mechanism Research

The precise molecular choreography of Vir protein-mediated T-DNA processing remains a model for inter-kingdom macromolecular transfer. Current research frontiers include structural biology of the relaxosome-T4SS interface, single-molecule dynamics of T-strand transfer, and re-engineering the system for targeted DNA integration in eukaryotic cells (including human therapeutics). This mechanistic understanding, framed within ongoing Ti plasmid research, directly enables the rational design of next-generation bioengineering vectors.

This whitepaper details the pivotal achievement in plant biotechnology: the disarming of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid to engineer versatile binary vector systems. This milestone is a cornerstone of a broader thesis investigating the fundamental molecular mechanisms of Ti plasmid biology and the precise function of T-DNA border sequences. The disarming process, which involved the strategic deletion of oncogenic and catabolic genes while preserving the virulence (vir) region and T-DNA borders, transformed a pathogenic natural vector into a safe and programmable tool for plant transformation. This advancement directly enabled the stable integration of any gene of interest into plant genomes, revolutionizing basic plant research and the development of genetically modified crops, with profound implications for agriculture and pharmaceutical production.

Core Technical Principles: From Wild-Type Ti to Disarmed Binary Vectors

The wild-type Ti plasmid (~200-250 kbp) contains two functionally critical regions:

- T-DNA Region: Flanked by 25-bp direct repeat border sequences (LB, RB), this segment is transferred and integrated into the plant genome. It carries oncogenes (iaaM, iaaH, ipt) for phytohormone synthesis causing crown gall disease, and opine synthesis genes (nos, ocs).

- Vir Region: A ~35-40 kbp locus containing virA, virG, virD1/D2, virE2, etc., responsible for processing the T-DNA and mediating its transfer.

The Disarming Process entailed the precise deletion of the oncogenes and opine synthesis genes from the T-DNA region, creating a "disarmed" Ti plasmid. The large size and complexity of the remaining Ti plasmid made direct cloning difficult. The binary vector system solved this by separating functions:

- Helper Ti Plasmid: A disarmed, non-oncogenic Ti plasmid resident in Agrobacterium, retaining the entire vir region but with the T-DNA region replaced by a neutral DNA segment (e.g., pAL4404 in strain LBA4404, pEHA101 in strain EHA105).

- Binary Vector (pBin): A small, E. coli-compatible plasmid containing the gene of interest flanked by the T-DNA LB and RB sequences, along with a plant-selectable marker (e.g., nptII for kanamycin resistance) and a bacterial selection marker.

The vir genes in trans on the helper plasmid recognize the borders on the binary vector and mobilize the intervening T-DNA into the plant cell.

Current State-of-the-Art: Modern binary vectors (e.g., Golden Gate/Gateway-compatible modules, CRISPR-Cas9 expression vectors) are highly sophisticated. They feature multiple cloning sites, visual markers (e.g., GFP, GUS), tissue-specific promoters, and hyper-virulent helper strains (e.g., AGL1 with pTiBo542 ΔT-DNA) for enhanced efficiency in diverse plant species.

Table 1: Evolution of Key Ti and Binary Vector Plasmid Characteristics

| Plasmid/System | Approx. Size (kbp) | Oncogenic? | Opine Synthesis? | Key Functional Components | Transformation Efficiency (Relative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type Ti (e.g., pTiA6) | 200-250 | Yes | Yes (nopaline) | Full T-DNA (oncogenes), vir region, opine catabolism | N/A (Pathogenic) |

| Disarmed Ti (e.g., pAL4404) | ~200 | No | No | ΔT-DNA (oncogenes/opines), intact vir region | Used as helper |

| Early Binary Vector (e.g., pBIN19) | ~12 | No | No | LB/RB, MCS, nptII, lacZα, Kan^R^ (bacterial) | 1x (Baseline) |

| Advanced Binary Vector (e.g., pCAMBIA1300) | ~12 | No | No | LB/RB, hptII (hygromycin R), gusA, multiple cloning site | 1-5x |

| Hyper-virulent Helper Strain (e.g., EHA105/AGL1) | Helper: ~150 | No | No | Disarmed pTiBo542 (larger vir region), chromosomal virG mutation | 5-20x (in recalcitrant species) |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Plant Selectable Marker Genes Used in Binary Vectors

| Marker Gene | Encoded Protein | Selective Agent | Mode of Action | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nptII | Neomycin phosphotransferase II | Kanamycin / Geneticin | Inactivates aminoglycoside antibiotics | 50-100 mg/L (kanamycin) |

| hptII/hph | Hygromycin phosphotransferase | Hygromycin B | Inactivates hygromycin B | 10-50 mg/L |

| bar/pat | Phosphinothricin acetyltransferase | Phosphinothricin (Bialaphos/Glufosinate) | Detoxifies herbicide | 2-10 mg/L |

| epsps/aroA | 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase | Glyphosate | Herbicide-resistant target enzyme | 1-10 mM |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Construction of a Basic Binary Vector via Restriction/Ligation

Objective: Clone a gene of interest (GOI) between the T-DNA borders of a binary vector backbone. Materials: pBIN19 or similar backbone, purified GOI PCR product, restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, competent E. coli DH5α, LB agar plates with kanamycin (50 µg/mL). Method:

- Digest both the binary vector backbone and the GOI PCR product with compatible restriction enzymes (e.g., XbaI and BamHI). Heat-inactivate enzymes.

- Purify digested DNA fragments using a gel extraction kit.

- Set up ligation reaction: 50 ng vector, 3:1 molar ratio of GOI insert, 1x T4 ligase buffer, 1 µL T4 DNA ligase. Incubate at 16°C for 16 hours.

- Transform 2-5 µL of ligation mix into chemically competent E. coli DH5α via heat-shock (42°C for 45 sec). Recover in SOC medium for 1 hour.

- Plate onto LB-Kanamycin plates. Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Screen colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest of miniprep DNA to confirm correct insertion.

Protocol 2:Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation ofArabidopsis thaliana(Floral Dip)

Objective: Stably transform Arabidopsis using a binary vector in Agrobacterium. Materials: A. thaliana (ecotype Col-0) plants at early bolting stage, Agrobacterium strain GV3101 carrying the binary vector, 5% sucrose solution, Silwet L-77. Method:

- Inoculate a single colony of Agrobacterium in 5 mL LB with appropriate antibiotics. Grow overnight at 28°C, 220 rpm.

- Centrifuge culture at 5000 x g for 10 min. Resuspend pellet in 500 mL of 5% sucrose solution.

- Add Silwet L-77 to a final concentration of 0.02-0.05% (v/v). Mix gently.

- Invert primary inflorescences of healthy Arabidopsis plants into the Agrobacterium suspension for 30 seconds, ensuring good coverage.

- Lay dipped plants horizontally in a tray, cover with clear plastic to maintain humidity for 24 hours.

- Return plants to normal growth conditions. Allow seeds to mature and dry (T1 seeds).

- Surface-sterilize T1 seeds and sow on selective medium (½ MS agar with appropriate antibiotic, e.g., 50 µg/mL kanamycin) to identify transgenic plants.

Diagrams and Visualizations

Title: Evolution from Wild-Type Ti Plasmid to Binary Vector System

Title: Binary Vector Construction and Plant Transformation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Ti Plasmid and Binary Vector Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Disarmed Agrobacterium Strains | Provide vir genes in trans for T-DNA transfer. | LBA4404 (pAL4404), GV3101 (pMP90), EHA105/AGL1 (pTiBo542 ΔT-DNA). |

| Binary Vector Backbones | Small plasmids for easy cloning of GOI between T-DNA borders. | pBIN19, pCAMBIA series, pGreen, pMDC series (Gateway). |

| Plant Selectable Marker Genes | Enable selection of transformed plant cells. | nptII (kanamycin R), hptII (hygromycin R), bar (glufosinate R). |

| Agrobacterium Electrocompetent Cells | For high-efficiency transformation of large binary vectors. | 1 mm gap cuvette, 1.8-2.5 kV, 25 µF, 200 Ω typical settings. |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces the vir gene expression cascade. | 100-200 µM in co-culture medium, dissolved in DMSO. |

| Silwet L-77 | Surfactant that reduces surface tension for efficient Arabidopsis floral dip. | Used at 0.02-0.05% (v/v) in sucrose dipping solution. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Support growth and regeneration of plant explants post-transformation. | Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal medium, with vitamins and hormones. |

| T-DNA Border Sequence Oligos | For PCR verification of border integrity and analysis of insertion sites. | LB primer: 5'-GCATCTGACGCATAACGACG-3' (example for pBIN19). |

| Gateway or Golden Gate Cloning Kits | Modern, efficient systems for assembling multiple DNA parts in binary vectors. | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Gateway), BsaI/BbsI enzyme kits (Golden Gate). |

Within the broader thesis on Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and T-DNA border sequence research, a central pillar remains the unparalleled efficiency of the native border sequences for stable genomic integration in plants and, increasingly, in non-plant eukaryotic systems. This document articulates the core biochemical and genetic principles underpinning this enduring status, supported by contemporary data and methodologies.

The Molecular Mechanism: Precision in Processing and Transfer

The 25-base-pair imperfect direct repeats that delineate the T-DNA borders are not merely markers for excision. They are precisely recognized by the VirD1/VirD2 endonuclease complex. VirD2 cleaves between the 3rd and 4th nucleotides of the bottom strand, becoming covalently attached to the 5’ end (the right border, RB, is the leading end). This nicked strand is displaced and replaced by synthesis from the left border (LB), forming the T-strand complex (T-complex). The attached VirD2 piloted into the host cell nucleus, where it facilitates integration.

Diagram: T-DNA Border-Mediated Transfer and Integration Pathway

Quantitative Evidence: Efficiency and Fidelity

The supremacy of native T-DNA borders is quantitatively demonstrated across multiple metrics compared to engineered alternatives (e.g., homing endonucleases, transposon systems, or CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR). The following table summarizes key comparative data from recent studies (2020-2023).

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Stable Integration Systems in Plants

| System | Transformation Efficiency (%) | Copy Number (Mode) | Intact Transgene Insertion (%) | Off-Target Integration Events | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native T-DNA Borders | 60-95 (in model plants) | 1-2 | 70-90 | Very Low | (Pitzschke, 2020) |

| Engineered/Short Borders | 15-40 | 1-5 | 30-60 | Low | (Shi et al., 2022) |

| CRISPR-Cas9 HDR | 0.1-5 | 1 | >95 | High (DSBs) | (Lee et al., 2021) |

| Maize Ac/Ds Transposon | 20-50 | 1-3 | 50-80 | Moderate (excision footprints) | (Roth et al., 2022) |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Border-Driven Integration

This protocol details the classic Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation assay in Arabidopsis thaliana (floral dip), followed by molecular analysis of integration patterns.

Title: Molecular Analysis of T-DNA Integration Junctions. Objective: To confirm precise border-mediated integration and determine copy number. Materials:

- Agrobacterium strain GV3101 harboring binary vector with gene of interest.

- Arabidopsis thaliana plants (ecotype Col-0) at early bolting stage.

- Silwet L-77 surfactant.

- LB agar plates with appropriate antibiotics (rifampicin, gentamicin, kanamycin).

- CTAB-based plant genomic DNA extraction kit. Procedure:

- Bacterial Culture & Floral Dip: Grow Agrobacterium to late-log phase. Resuspend in 5% sucrose + 0.03% Silwet L-77. Dip inflorescences for 30 seconds. Grow plants to seed set (T1 generation).

- Selection: Surface-sterilize T1 seeds, plate on agar containing the plant-selective antibiotic (e.g., kanamycin). Resistant seedlings are putative transformants.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest leaf tissue from T1 plants, extract DNA using CTAB method.

- PCR for Border Junctions:

- Perform two separate PCRs per plant.

- RB Junction: Use a primer specific to the plant genomic region upstream of the LB (or a generic left-border primer) paired with a primer inside the T-DNA.

- LB Junction: Use a primer specific to the plant genomic region downstream of the RB paired with a primer inside the T-DNA.

- Amplify, clone, and sequence products to identify precise integration sites and microhomologies.

- Southern Blot Analysis: Digest genomic DNA with a restriction enzyme that cuts once within the T-DNA. Probe with the transgene sequence. The number of hybridizing bands indicates copy number.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for T-DNA Border Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector System (e.g., pCAMBIA, pGreen) | Contains T-DNA borders, MCS, plant selectable marker, and bacterial origin for Agrobacterium use. | Cambia; www.addgene.org |

| Agrobacterium Strain (e.g., GV3101, LBA4404) | Disarmed Ti plasmid helper strain providing vir genes in trans for T-DNA processing. | CIB, NCPPB, commercial vendors |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound inducing the vir gene region, essential for T-DNA excision. | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher |

| Selective Antibiotics (Plant) | For in vitro selection of transformed tissue (e.g., Kanamycin, Hygromycin B). | Various biological suppliers |

| Silwet L-77 or Tween-20 | Surfactant critical for floral dip transformation, promoting bacterial entry. | Lehle Seeds; Sigma-Aldrich |

| Border-Specific Primers | For amplifying and sequencing plant-T-DNA junctions to verify precise integration. | Custom oligo synthesis services |

| TAIL-PCR or HiTAIL-PCR Kit | For efficiently isolating unknown genomic sequences flanking integrated T-DNA. | Takara Bio; published protocols |

Logical Framework: Why Borders Are Unrivaled

The following diagram synthesizes the logical argument for the gold-standard status of T-DNA borders, integrating mechanistic, practical, and outcome-based factors.

Diagram: Logical Framework for T-DNA Border Gold Standard Status

Within the ongoing thesis of Ti plasmid research, the T-DNA border sequences endure as the gold standard due to their evolutionarily optimized role in a natural genetic exchange process. They provide an unmatched combination of high efficiency, precise low-copy integration, and experimental robustness. While newer genome-editing tools offer site-specificity, the border-mediated process remains the most reliable method for delivering and stably integrating large, intact DNA segments across diverse species, securing its central role in both basic research and applied biotechnology.

Engineering with Precision: Designing T-DNA Vectors and Transformation Protocols for Research & Bioproduction

Within the broader research on Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and T-DNA border sequences, the binary vector system stands as the foundational technology for plant transformation and, increasingly, for applications in biopharmaceutical production. This guide details the core components—the vector backbone, the T-DNA cassette, and selectable markers—from a technical perspective, providing protocols and data essential for researchers and drug development professionals engineering plants for molecular farming or therapeutic protein production.

System Architecture & Core Components

The Binary Vector Principle

Binary systems separate the T-DNA delivery machinery (vir genes) on a helper Ti plasmid (disarmed) from the T-DNA itself, which is cloned on a separate, smaller, E. coli-compatible binary vector. This separation simplifies molecular cloning while maintaining efficient T-DNA transfer.

The Vector Backbone

The backbone contains all sequences required for replication and selection in both E. coli and Agrobacterium.

Table 1: Common Replication Origins and Selection Markers in Binary Vector Backbones

| Component | Type | Common Examples | Host Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replication Origin | High-copy in E. coli | pUC ori, ColE1 | E. coli | Facilitates plasmid propagation in E. coli for cloning. |

| Replication Origin | Broad-host-range | pVS1, pRi | Agrobacterium, E. coli | Enables stable maintenance in Agrobacterium. |

| Bacterial Selectable Marker | Antibiotic Resistance | kanR, specR, gentR | E. coli & Agrobacterium | Selection for plasmid-containing bacteria. |

The T-DNA Cassette

The T-DNA is delineated by left and right border sequences (LB, RB) and contains the genetic cargo for transfer into the plant genome.

Left Border (LB) & Right Border (RB): 24-bp imperfect direct repeats. The RB is critical for initiation of transfer; LB often defines the termination point. Recent research on border sequence polymorphisms shows transfer efficiency can vary significantly.

T-DNA Cargo: Typically includes:

- Selectable Marker Gene: For selection of transformed plant tissue (see Section 2.4).

- Gene(s) of Interest (GOI): Driven by a constitutive (e.g., CaMV 35S) or inducible promoter.

- Scorable Marker Gene (Optional): e.g., gusA (β-glucuronidase) or gfp (green fluorescent protein) for rapid screening.

Table 2: Common Plant-Expressible Promoters Used in T-DNA Cassettes

| Promoter | Source | Expression Pattern | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaMV 35S | Cauliflower Mosaic Virus | Constitutive, strong | High-level expression of GOIs. |

| Ubiquitin (Ubi) | Maize | Constitutive, strong | Monocot transformation. |

| NOS | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Constitutive, moderate | Often drives selectable markers. |

| Rd29A | Arabidopsis | Stress-inducible | Controlled expression of therapeutic proteins. |

Diagram 1: Simplified T-DNA Cassette Structure

Selectable Markers

Selectable markers are crucial for identifying successfully transformed plant cells. Trends in pharmaceutical-grade design favor non-antibiotic markers.

Table 3: Categories of Plant Selectable Markers

| Category | Example Gene | Selective Agent | Mode of Action | Key Advantage/Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Resistance | nptII (kanamycin resistance) | Kanamycin, Geneticin | Inactivates aminoglycoside antibiotics. | Well-established; public perception issues for pharma crops. |

| Herbicide Tolerance | bar or pat (phosphinothricin acetyltransferase) | Glufosinate, Bialaphos | Detoxifies herbicide. | Effective for many species; regulatory considerations. |

| Metabolic/Positive Selection | pmi (phosphomannose isomerase) | Mannose | Enables metabolism of mannose as carbon source. | Non-antibiotic, safe; requires specific media. |

| Hormone Biosynthesis | ipt (isopentenyl transferase) | None (cytokinin overproduction) | Alters hormone balance to promote shoots. | Chemical-free; can cause morphological abnormalities. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assembly of a Binary Vector via Golden Gate Cloning

This modular method is currently preferred for stacking multiple genes in the T-DNA.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Design: Ensure all modules (promoter, GOI, terminator, marker) have compatible, unique 4-bp overhangs for directional assembly. Flank the entire T-DNA with LB and RB modules.

- Digestion-Ligation: Set up a 20 µL reaction:

- 50 ng of each DNA module.

- 1 µL T4 DNA Ligase (high concentration).

- 1 µL Type IIS restriction enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2).

- 2 µL 10x T4 Ligase Buffer.

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL.

- Thermocycling: Cycle as follows: 37°C (2 min) → 16°C (5 min), 30 cycles; then 50°C (5 min); 80°C (5 min).

- Transformation: Transform 2 µL of the reaction into competent E. coli. Screen colonies by colony PCR or diagnostic digest.

- Mobilization to Agrobacterium: Introduce the verified binary vector into disarmed A. tumefaciens (e.g., strain LBA4404 or GV3101) via electroporation or freeze-thaw transformation.

Protocol: Assessing T-DNA Transfer Efficiency using GUS Histochemical Assay

A standard assay to visualize successful T-DNA delivery before stable transformation.

Method:

- Co-cultivation: Inoculate plant explants (e.g., leaf discs) with Agrobacterium harboring the binary vector with an intron-containing gusA gene in the T-DNA.

- Rinse & Incubate: After 2-3 days co-culture, rinse explants thoroughly with sterile water containing carbenicillin (500 mg/L) to kill Agrobacterium.

- GUS Staining: Immerse explants in GUS staining solution (see Toolkit). Apply vacuum infiltration for 5 min, then incubate at 37°C in the dark for 4-24 hours.

- Destaining: Remove chlorophyll by soaking in 70% ethanol. Observe blue staining under a stereomicroscope, indicating T-DNA transfer and transient expression.

Diagram 2: GUS Assay Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Binary Vector Work

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Disarmed A. tumefaciens Strain | Provides vir genes in trans for T-DNA processing and transfer. | LBA4404 (pAL4404 helper), GV3101 (pMP90 helper). |

| Golden Gate Assembly Kit | Modular cloning system for T-DNA construction. | BsaI-based kits with pre-formatted modules. |

| Plant Selection Antibiotic | Selects for transformed plant tissue post-co-cultivation. | Kanamycin (50-100 mg/L), Hygromycin B (10-50 mg/L). |

| GUS Staining Solution | Histochemical detection of β-glucuronidase activity. | 1 mM X-Gluc, 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide, 0.1% Triton X-100. |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces vir gene expression. | 100-200 µM in co-cultivation media. |

| Binary Vector Backbone | Cloning vector with broad-host-range ori and plant marker. | pCAMBIA, pGreen, pEAQ-HT-DEST series. |

The Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and its transfer-DNA (T-DNA) system represent a paradigm for horizontal gene transfer and a cornerstone of plant biotechnology. The core mechanism relies on precise recognition and processing of specific border sequences flanking the T-DNA. This technical guide delves into the optimization of these critical cis-elements: the 25-bp direct border repeats (BRs), their orientation, the role of the overdrive sequence, and the functional consequences of border truncations. Understanding these parameters is essential for enhancing T-DNA delivery efficiency, controlling copy number and integration structure in transgenic organisms, and refining the system for advanced applications in synthetic biology and drug development.

The Anatomy of a T-DNA Border: Core Components and Functions

The right border (RB) and left border (LB) are imperfect direct repeats, with the RB being correctly processed by the VirD1/VirD2 endonuclease complex with high efficiency. The consensus 25-bp sequence is: 5'-TGTACACAAATTGGCAGGATATAT-3' (with variations, especially in bases 9-12). Critical to its function is the overdrive sequence, a cis-element located adjacent to the RB (and sometimes LB) that dramatically enhances T-DNA processing and transfer.

Table 1: Comparison of Border Repeat Configurations and Relative Transfer Efficiencies

| Border Configuration | Description | Relative T-DNA Transfer Efficiency (%)* | Key Feature / Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical RB + OD | Full 25-bp RB with adjacent 24-bp overdrive | 100 (Baseline) | Maximum efficiency for full-length T-DNA transfer. |

| Canonical RB (no OD) | Full 25-bp RB without overdrive | 10 - 30 | Demonstrates critical enhancer role of overdrive. |

| Inverted RB | 25-bp sequence in reverse orientation | < 1 | Negligible processing; used to block read-through. |

| Truncated RB (20-bp) | First 20 bp of consensus | 40 - 70 | Reduced but significant activity; used for size-constrained vectors. |

| Truncated RB (15-bp) | First 15 bp of consensus | 5 - 15 | Very low activity; rarely functional alone. |

| Canonical LB + OD | Full LB with overdrive | 1 - 5 (as RB) | Can function as an RB if overdrive is present. |

| Canonical LB (no OD) | Standard LB sequence | < 0.1 | Primarily acts as a termination signal. |

| Direct Repeat LBx2 | Two LB sequences in direct repeat | ~80 | Increases precise termination, reduces vector backbone transfer. |

Data synthesized from recent studies (2021-2024) using binary vector systems in *Arabidopsis and rice. Efficiency is measured by stable transformation frequency relative to the canonical RB+OD control.* *Efficiency here refers to precision of left border cleavage, not transfer increase.*

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Border Function

Protocol:In VivoT-DNA Processing Assay (Virulence Induction & Southern Blot)

Objective: To visualize the generation of T-DNA strand (T-strand) intermediates, dependent on border sequence integrity.

- Strain & Vector: Agrobacterium strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101) harboring the binary vector of interest and a helper Ti plasmid (e.g., pTiA6).

- Induction: Grow bacterial culture to mid-log phase (OD600=0.5-0.8) in minimal medium. Induce vir gene expression by shifting to induction medium (pH 5.5-5.6) supplemented with acetosyringone (100-200 µM) for 12-24 hours.

- Nucleic Acid Isolation: Harvest cells. Isolate large molecular weight DNA using a modified alkaline lysis method.

- Southern Blotting: Digest DNA with restriction enzymes that cut within the T-DNA and once in the vector backbone. Perform gel electrophoresis and transfer to a membrane.

- Probing: Hybridize with a digoxigenin-labeled probe complementary to the T-DNA region adjacent to the border being tested. The appearance of a single-stranded T-strand signal indicates successful border processing.

Protocol: Quantitative Transient Transformation Assay (GUS/GFP)

Objective: To rapidly compare the functional efficiency of different border constructs.

- Vector Construction: Create a series of binary vectors where the gene for β-glucuronidase (GUS) or green fluorescent protein (GFP) is driven by a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., 35S) and flanked by the border variants under test.

- Agroinfiltration: Introduce vectors into Agrobacterium. Resuspend induced cultures in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 µM acetosyringone). Infiltrate into leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana.

- Quantification:

- GUS: Harvest leaf discs 2-3 days post-infiltration. Homogenize and assay fluorometrically using 4-MUG as substrate. Express activity as pmol 4-MU/min/mg protein.

- GFP: Image under standardized confocal or fluorescence microscopy settings at 48h. Quantify mean fluorescence intensity per unit area using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

- Analysis: Normalize values to the canonical RB+OD control set at 100%. Statistical analysis (ANOVA) is required across multiple biological replicates.

Protocol: Analysis of T-DNA Integration Junctions (PCR & Sequencing)

Objective: To assess the precision of border truncation and its effect on integration structure.

- Plant Material: Generate stable transgenic lines using vectors with defined border truncations.

- Genome Walking: Use techniques like TAIL-PCR or adapter-ligation PCR to isolate plant genomic DNA flanking the integrated T-DNA's left and right junctions.

- Sequencing & Alignment: Sequence the amplified fragments. Align sequences to the original binary vector and the plant genome to determine:

- Microhomologies at the junction.

- Exact point of T-DNA truncation relative to the border sequence.

- Presence of vector backbone sequences beyond the borders.

Diagram: T-DNA Border Processing and Key Optimization Parameters

Diagram Title: T-DNA Border Processing & Optimization Levers

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Border Sequence Research

| Item | Function & Application | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector Kits | Modular systems for easy assembly of T-DNA constructs with custom borders. | Golden Gate MoClo Toolkits, Gateway-compatible pBIN vectors. |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Disarmed helper strains for transformation. Strain choice affects efficiency. | GV3101 (pMP90), LBA4404, AGL-1 (for recalcitrant species). |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces the vir gene region on the Ti plasmid. | 98% purity, dissolved in DMSO for stock solution (100 mM). |

| Vir Gene Inducers | Alternative or supplemental inducers for specific plant species. | Sinapinic acid, hydroxyacetosyringone. |

| GUS Assay Kit | For quantitative fluorometric analysis of transient T-DNA delivery. | Fluorometric GUS assay kit with 4-MUG substrate. |

| Plant Genomic DNA Kit | High-quality DNA extraction for Southern blot and junction analysis. | CTAB-based or column-based kits for polysaccharide-rich tissues. |

| Thermostable Polymerases for GC-rich DNA | PCR amplification of border and overdrive sequences (high AT/GC content). | KAPA HiFi, Phusion U Green (high fidelity). |

| Genome Walking Kit | Systematically clone unknown flanking sequences of integrated T-DNA. | TAIL-PCR kits or adapter ligation PCR systems. |

| Methylation-Free E. coli | Host for cloning binary vectors to avoid plant-silencing prone methylation. | E. coli strains like JM110, DAM-/DCM- deficient. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | For stable transformation and regeneration of test plants. | Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal media with specific hormones. |

Discussion and Future Directions: Implications for Drug Development

Optimized border sequences directly impact the efficiency and precision of plant-made pharmaceutical (PMP) production. High-efficiency RB/OD constructs enable rapid, high-yield transient expression of therapeutic proteins in Nicotiana hosts. Conversely, paired, truncated borders can favor single-copy, backbone-free integrations crucial for stable, regulatory-compliant master seed lines. Future research is exploring synthetic border-like sequences with enhanced VirD2 affinity and the development of "directional" T-DNA systems using asymmetric borders, which could revolutionize multigene pathway engineering for complex natural product synthesis in plants. The continued deconstruction of border function remains critical for advancing Agrobacterium-mediated delivery as a versatile tool for genome engineering beyond plants, including in human cell therapy applications.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens, the causative agent of crown gall disease in plants, has been engineered as a powerful vector for genetic transformation. Its utility extends far beyond its natural plant hosts. This whitepaper, framed within broader research on the Ti plasmid and T-DNA border sequences, provides an in-depth technical examination of AMT applications in fungi (including filamentous fungi and yeasts) and human cells. We detail the molecular mechanisms, present comparative quantitative data, and provide standardized experimental protocols to enable researchers in biotechnology and drug development to harness this versatile tool.

The foundational thesis of Agrobacterium research posits that the tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid machinery, specifically the vir (virulence) region and the transfer-DNA (T-DNA) delimited by 25-bp direct repeat border sequences (LB, RB), is a highly adaptable natural genetic engineer. While evolved for plant transformation, the system's core function—single-stranded T-DNA transfer and integration—is largely host-agnostic. This discovery has pivoted the field from phytopathology to a platform technology for diverse eukaryotes.

Molecular Mechanism of AMT in Non-Plant Hosts

The process mirrors plant transformation: perception of host-specific signals (e.g., acidity, phenolics for plants; unknown cues for others) activates the vir regulon via VirA/VirG. The T-DNA is nicked at the borders, and the single-stranded T-DNA complex (T-strand) is exported via a Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) into the host cell. Subsequent nuclear import and integration rely on host machinery, explaining the system's broad applicability.

Diagram 1: Core AMT Mechanism for Non-Plant Hosts

Comparative Quantitative Data

Table 1: Efficiency & Key Parameters of AMT Across Kingdoms

| Host System | Typical Efficiency (Transformants/10^6 cells) | Optimal Co-culture Conditions | Key Modifications Required | Primary Integration Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filamentous Fungi (e.g., Aspergillus) | 10 - 500 | 22-25°C, 2-3 days, 200 µM AS | Acetosyringone (AS) induction; Fungal selectable marker (e.g., hph, pyrG) | Random, often single-copy. |

| Yeast (e.g., Saccharomyces) | 1000 - 10,000 | 28-30°C, 2 days, 200 µM AS | AS induction; Yeast markers (e.g., URA3, LEU2). | Highly efficient, mostly random. |

| Human Cells (e.g., HEK293, HCT116) | 0.1 - 5% (Transfection %) | 37°C, 5% CO2, 24-48h, 200 µM AS | AS induction; virE1 mutation (disarmed helper); Mammalian promoter/selection. | Random, but can be targeted with CRISPR donor constructs. |

| Plant Cells (Control) | 100 - 10,000 (calli/explants) | 22-28°C, 2-3 days, 200 µM AS | None (native host). | Random, often multicopy. |

Table 2: Essential Border Sequence Variations

| Border Sequence Type | Sequence (5' -> 3') | Relative Efficiency in Non-Plant Hosts* | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type Octopine RB | TAGGCAGGATATATNNNNNNGTAAAAC | 1.0 (Reference) | Standard for most AMT vectors. |

| Superborder (Overdrive) | TGTTTGTTTGAAATTTTTCTAAATGTAAG | 1.5 - 3.0 | Enhances T-strand production; boosts yeast/fungal AMT. |

| Mutated/Attenuated LB | TAGGCAGGATATATNNNNNNaGaaAC | 0.1 - 0.5 | Reduces vector backbone transfer; cleaner transformations. |

*Efficiency relative to standard RB in yeast AMT assays.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: AMT ofSaccharomyces cerevisiae

Objective: Integrate a expression cassette into the yeast genome.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Electroporate the binary vector (with yeast URA3 marker and expression cassette) into A. tumefaciens strain LBA1100 (containing a disarmed Ti plasmid with a virG mutation). Grow on LB agar with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., spectinomycin, rifampicin) at 28°C for 2 days.

- Induction: Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL MinA medium with antibiotics and 200 µM acetosyringone (AS). Grow overnight at 28°C, 250 rpm.

- Yeast Preparation: Grow yeast (ura3-) overnight in YPD at 30°C.

- Co-culture: Mix induced Agrobacterium (OD600 ~1.0) with yeast cells (OD600 ~2.0) at a 10:1 (Agro:Yeast) ratio on a nitrocellulose filter placed on induction medium agar (IM, pH 5.3, 200 µM AS). Co-culture for 2 days at 22-24°C.

- Selection: Wash cells from the filter and plate on yeast minimal medium lacking uracil, supplemented with cefotaxime (200 µg/mL) to kill Agrobacterium. Incubate at 30°C for 3-5 days.

- Analysis: Pick colonies for PCR and Southern blot to confirm integration.

Protocol 4.2: AMT of Human HEK293T Cells

Objective: Deliver a CRISPR-Cas9 donor DNA template for targeted integration.

Materials: See toolkit. Method:

- Strain & Vector: Use A. tumefaciens strain LBA4404.thy- (harboring a disarmed pAL4404 Ti plasmid). The binary vector must contain left and right borders flanking the donor DNA with a mammalian selection marker (e.g., puromycin resistance).

- Agrobacterium Induction: Grow Agrobacterium to mid-log phase in LB with antibiotics. Pellet and resuspend in cell culture medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) containing 200 µM AS. Incubate for 2h at 25°C.

- Co-culture with Human Cells: Seed HEK293T cells in a 6-well plate to reach 60-70% confluency. Replace medium with the induced Agrobacterium suspension (MOI ~100:1). Centrifuge plate at 600 x g for 10 min to facilitate contact.

- Incubation: Co-culture at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24-48 hours.

- Recovery & Selection: Remove medium, wash cells with PBS, add fresh medium with cefotaxime (300 µg/mL) for 48h to kill bacteria. Then, add puromycin (1-2 µg/mL) for 7-10 days to select transfectants.

- Analysis: Screen pools or clones via genomic PCR and sequencing for targeted integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in AMT | Example/Supplier Note |

|---|---|---|

| Acetosyringone (AS) | Phenolic compound that activates the vir gene cascade. Essential for non-plant AMT. | Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# D134406. Prepare 100 mM stock in DMSO. |

| Binary Vector System | Plasmid containing T-DNA borders, selectable marker, and MCS, mobilized into Agrobacterium. | pCAMBIA, pGreen series, or custom vectors with enhanced borders. |

| Disarmed Agrobacterium Strain | Strain with modified Ti plasmid (vir genes present, oncogenes removed). | LBA4404, GV3101, AGL-1 (for fungi). LBA1100 (virG mutant) for yeast. |

| Co-culture Medium (IM) | Induction Medium, low phosphate, adjusted pH (5.3-5.7), contains AS. | Per L: 2.05g K2HPO4*3H2O, 0.54g NaH2PO4, 0.15g NaCl, 0.5g glucose, 0.5g glycerol, 1.19g Hepes, adjust pH. |

| Cefotaxime / Timentin | β-lactam antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium after co-culture without harming eukaryotic cells. | Use 200-500 µg/mL in final selection plates/media. |

| Host-Specific Selectable Markers | Genes enabling selection of transformed eukaryotic cells. | Fungi: hygromycin B phosphotransferase (hph). Yeast: URA3, LEU2. Mammalian: puromycin N-acetyltransferase, neomycin resistance. |

| Superborder / Overdrive Sequence | Enhancer sequence placed adjacent to RB to increase T-DNA transfer efficiency. | Can be synthesized and cloned into binary vector backbones. |

Advanced Applications & Future Directions

AMT is now a cornerstone for genome editing in fungi, facilitating high-throughput gene knockout libraries. In human cells, its primary advantage is the ability to deliver large, complex DNA cargos (e.g., whole cDNA, multiple expression cassettes) with minimal cytotoxicity compared to physical methods. The frontier lies in engineering the T4SS and vir proteins for enhanced tropism towards animal cells, and coupling AMT with site-specific nucleases (CRISPR-Cas) for precise, "trait stacking" integrations—a direct extension of border sequence research aimed at controlling integration outcomes.

Diagram 2: AMT Applications & Future Directions

This whitepaper details high-throughput methodologies for plant transformation, framed within ongoing research into Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and T-DNA border sequence engineering. Optimizing T-DNA transfer efficiency and cargo capacity remains a central challenge in agricultural biotechnology and pharmaceutical compound production in plants. The Gateway cloning system and subsequent modular assembly platforms provide robust, standardized pipelines for rapidly constructing complex T-DNA vectors, enabling systematic study of border sequence requirements and high-throughput functional genomics.

Core Technology: Gateway Cloning Recombination

Gateway technology is a site-specific recombination system based on bacteriophage lambda's att sites and the corresponding integrase/excisionase enzymes. This system enables the efficient, directional transfer of DNA fragments between vectors.

Key att Sites:

- attB: ~25 bp sequence on a donor molecule (PCR product or entry clone).

- attP: ~242 bp sequence on a donor vector.

- attL: Hybrid site formed after recombination between attB and attP.

- attR: Hybrid site formed after recombination between attP and attB.

BP Reaction: attB x attP → attL + attR. Used to clone a PCR product into an Entry Vector. LR Reaction: attL x attR → attB + attP. Used to transfer a gene from an Entry Clone into a Destination Vector (e.g., a plant transformation vector).

Detailed LR Cloning Protocol (for Plant Expression Vector Construction):

- Setup: In a microcentrifuge tube, combine:

- 150 ng Entry Clone (containing gene of interest flanked by attL sites).

- 150 ng Destination Vector (containing T-DNA borders, selectable marker, and attR sites).

- TE Buffer, pH 8.0 to 2 µl.

- Add Enzyme Mix: Add 1 µl of LR Clonase II enzyme mix (contains Integrase and Excisionase).

- Incubate: Mix gently and incubate at 25°C for 1-18 hours.

- Stop Reaction: Add 1 µl of Proteinase K solution (2 µg/µl) and incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes.

- Transform: Use 2 µl of the reaction to transform competent E. coli cells (e.g., DH5α).

- Screen: Select colonies on appropriate antibiotic plates (determined by the Destination Vector's backbone marker). Confirm recombination via colony PCR or restriction digest.

Modular Assembly Systems (Golden Gate, MoClo)

For higher-throughput assembly of multiple DNA parts (promoters, coding sequences, terminators) into a single T-DNA, modular systems are employed.

Golden Gate Assembly uses Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI, BbsI) that cut outside their recognition sequence, generating unique, user-defined overhangs. This allows for scarless, directional, and one-pot assembly of multiple fragments.

Detailed Golden Gate Protocol for T-DNA Module Assembly:

- Design & Preparation: Design DNA parts (promoter, CDS, terminator) flanked by appropriate Type IIS sites (e.g., 5'-GGTCTC N...-3' for BsaI). Parts are typically cloned in Level 0 acceptor plasmids.

- Assembly Reaction: In a single tube, combine:

- 50-100 ng of each Level 0 plasmid (equimolar).

- 1 µl BsaI-HFv2 restriction enzyme (cuts at designed sites).

- 1 µl T4 DNA Ligase (ligates compatible overhangs).

- 2 µl 10x T4 DNA Ligase Buffer.

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µl.

- Thermocycling: Run the following program:

- 37°C for 2-5 minutes (digestion).

- 16°C for 5 minutes (ligation).

- Repeat cycles 25-50 times.

- Final digestion: 60°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold at 4°C.

- Transform & Screen: Transform 2-5 µl into E. coli. Screen for correct assembly using colony PCR or diagnostic digest.

Table 1: Comparison of Cloning Systems for Plant Vector Construction

| Parameter | Gateway LR Reaction | Golden Gate Assembly | Traditional Restriction/Ligation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly Type | Recombination | Restriction-Ligation | Restriction-Ligation |

| Directionality | Inherent | Designed via overhangs | Dependent on site uniqueness |

| Typical Assembly Time | 1-3 hours (reaction) | 2-6 hours (reaction) | 2-16 hours (plus fragment prep) |

| Efficiency (Correct Colonies) | >90% | 70-95% | 1-50% (highly variable) |

| Multi-Gene Assembly Capability | Limited (cassettes) | High (10+ parts in one pot) | Low (sequential) |

| Cost per Reaction | High (proprietary enzyme) | Moderate | Low |

Table 2: Impact of Vector System on Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Efficiency in Nicotiana benthamiana (Leaf Disc Assay)

| T-DNA Vector System | Average Transformation Efficiency (% Regenerants) | Standard Deviation (±%) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gateway-compatible Binary | 85% | 5.2 | Speed, reliability for single constructs |

| Golden Gate Modular Binary | 82% | 4.8 | Rapid combinatorial testing |

| Conventional Binary Vector | 78% | 10.5 | Flexibility, no licensing constraints |

Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Provider Examples | Function in High-Throughput Plant Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| pDONR/pENTR Vectors | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Entry vectors for BP recombination, containing attP sites and suicide gene (ccdB) for selection. |

| Plant Destination Vectors (e.g., pK7WG2, pB7m34GW) | VIB, ABRC | Binary vectors with attR sites, plant selectable markers (e.g., KanR), and T-DNA borders for Agrobacterium transformation. |

| LR Clonase II Enzyme Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Proprietary blend of Integrase and Excisionase for performing LR recombination reactions. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (BsaI-HFv2, BbsI-HF) | NEB | High-fidelity enzymes for Golden Gate assembly, cutting outside recognition sequences to generate custom overhangs. |

| Level 0 Acceptor Plasmids (e.g., pICH41308) | Addgene, IoC | Standardized, small plasmids for holding basic parts (promoters, CDS, terminators) for modular assembly systems. |

| Gateway-compatible ORFeome Libraries | Various consortia | Pre-made collections of Entry clones containing full-length ORFs, enabling rapid clone mobilization for functional screens. |

| Electrocompetent Agrobacterium Strains (GV3101, LBA4404) | Lab stocks, vendors | Engineered A. tumefaciens strains with disarmed Ti plasmids, ready for transformation with binary vectors for plant infiltration. |

| Plant Selection Agents (Kanamycin, Hygromycin B, Glufosinate) | Various | Antibiotics or herbicides corresponding to resistance markers on T-DNA, used to select transformed plant tissue. |

The study of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid and its T-DNA border sequences has evolved from understanding crown gall disease to pioneering plant genetic engineering. A core thesis in this field posits that the precision and efficiency of T-DNA transfer, governed by its 25-bp border sequences and Vir protein machinery, can be harnessed and optimized for stable, high-yield heterologous expression in plants. This whitepaper details the application of this principle in molecular pharming, where engineered T-DNA vectors are used to transform plants into bioreactors for the production of recombinant proteins (e.g., vaccines, antibodies) and valuable secondary metabolites (e.g., alkaloids, terpenoids).

T-DNA Vector Engineering for Pharming

Modern T-DNA vectors are typically binary systems, separating the T-DNA (on a small plasmid) from the vir genes. Key modifications include:

- Strong Constitutive or Inducible Promoters: e.g., CaMV 35S (constitutive), pRBCS (light-induced), or chemically inducible systems for temporal control.

- Targeting Signals: Sequences to direct proteins to subcellular compartments (apoplast, endoplasmic reticulum, chloroplasts) to enhance stability and accumulation.

- Selection Markers: Antibiotic (e.g., kanR) or herbicide resistance genes for transgenic selection.

- Gene Silencing Suppressors: Co-expression of proteins like p19 or HC-Pro to boost yields.

Table 1: Comparison of T-DNA Expression Platforms in Molecular Pharming

| Platform | Typical Yield Range | Key Advantages | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf-Based Transient | 0.1 - 5 g/kg FW* | Rapid (days), scalable, no stable integration | Vaccines, diagnostic antibodies, proof-of-concept |

| Stable Transgenic Plants | 0.01 - 2% TSP | Stable, heritable, potential for field cultivation | High-volume products (e.g., industrial enzymes) |

| Hairy Root Culture | 0.1 - 3% DW* | Genetically stable, excretes metabolites, in vitro | Secondary metabolites, recombinant proteins |

| Suspension Cells | 0.01 - 1 g/L | Controlled bioreactor conditions | Consistent, GMP-compliant protein production |

FW: Fresh Weight; TSP: Total Soluble Protein; *DW: Dry Weight

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Yield Transient Expression inNicotiana benthamianavia Agroinfiltration

Objective: Rapid production of recombinant protein for pre-clinical evaluation. Reagents: See The Scientist's Toolkit below. Procedure:

- Vector Preparation: Transform the engineered T-DNA binary vector into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 (or LBA4404) via electroporation.

- Agrobacterium Culture: Inoculate a single colony in 5 mL LB with appropriate antibiotics. Grow overnight at 28°C, 250 rpm.

- Induction: Dilute the culture 1:50 in fresh induction medium (LB, antibiotics, 10 mM MES pH 5.6, 20 μM acetosyringone). Grow to OD600 ~0.8.

- Cell Harvest & Resuspension: Pellet cells (4000 x g, 10 min). Resuspend in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 μM acetosyringone, pH 5.6) to a final OD600 of 0.5-1.0.

- Infiltration: Using a needleless syringe, infiltrate the suspension into the abaxial side of leaves of 4-6 week-old N. benthamiana plants.

- Incubation: Grow plants under normal conditions for 4-7 days.

- Harvest & Extraction: Harvest infiltrated leaf tissue. Homogenize in extraction buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer with protease inhibitors). Clarify by centrifugation (15,000 x g, 20 min, 4°C).

- Analysis: Quantify protein yield via ELISA or western blot and assess activity.

Protocol: Establishment of Hairy Root Cultures for Metabolite Production

Objective: Generate stable, transgenic root lines producing a target secondary metabolite. Procedure:

- Plant Material: Surface-sterilize seeds or explants (e.g., cotyledons, leaves) of the target plant species.

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Grow A. rhizogenes strain (e.g., R1000, ATCC 15834) carrying the metabolite pathway T-DNA vector as in 3.1 steps 1-3.

- Inoculation: Wound explants with a sterile needle dipped in the bacterial culture.

- Co-cultivation: Place explants on co-cultivation medium (hormone-free, solid) for 2-3 days in the dark.

- Decontamination & Root Induction: Transfer explants to hormone-free medium containing an antibiotic (e.g., cefotaxime) to kill Agrobacterium. Hairy roots emerge at wound sites within 1-3 weeks.

- Culture Establishment: Excise individual root tips and transfer to liquid culture medium. Maintain in the dark with shaking.

- Screening & Analysis: Screen lines for transgene integration (PCR) and quantify metabolite yield via HPLC-MS.