Advanced CRISPR Protocol for Primary Cells: A 2025 Guide from Foundations to Clinical Translation

This comprehensive guide details the latest protocols and advancements in CRISPR gene editing for primary human cells, a critical frontier for therapeutic development and functional genomics.

Advanced CRISPR Protocol for Primary Cells: A 2025 Guide from Foundations to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the latest protocols and advancements in CRISPR gene editing for primary human cells, a critical frontier for therapeutic development and functional genomics. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, state-of-the-art methodological workflows, advanced optimization strategies to overcome low HDR efficiency and cell viability challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks. The article synthesizes cutting-edge 2025 research, including digital microfluidics for low-input screening, enhanced nuclear localization signals (hiNLS) for improved editing, and insights from active clinical trials, providing a roadmap for translating CRISPR research into effective therapies.

Understanding Primary Cells and CRISPR Mechanics: Building a Solid Foundation

The transition from traditional immortalized cell lines to primary cells in therapeutic development represents a critical evolution in preclinical research. Primary cells, isolated directly from living tissue, maintain their biological identity and offer a closer representation of in vivo conditions compared to immortalized cell lines. This enhanced biological fidelity is particularly crucial in advanced therapeutic applications, especially CRISPR gene editing, where predicting human physiological responses is essential for reducing drug candidate attrition. While primary cells present technical challenges including limited lifespan and higher biological variability, recent methodological advances in delivery systems and protocol optimization now enable researchers to leverage their physiological relevance for more predictive disease modeling and therapeutic development.

The choice of cell model system serves as the foundational element in biomedical research, directly influencing the translational potential of therapeutic discoveries. Immortalized cell lines have been research staples for decades due to their convenience, but growing evidence indicates their limitations in predicting human physiological responses. Primary cells, characterized by their direct isolation from living tissues without genetic modification for perpetual division, provide a closer representation of native human biology. This application note examines the scientific and practical considerations between these model systems, with particular emphasis on their application in CRISPR-based therapeutic development, and provides detailed protocols for implementing primary cell models in gene editing workflows.

Comparative Analysis: Primary Cells vs. Immortalized Cell Lines

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of primary cells and immortalized cell lines

| Characteristic | Primary Cells | Immortalized Cell Lines |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Relevance | High - Closer to native morphology and function [1] [2] | Low - Often non-physiological (e.g., cancer-derived) [3] |

| Reproducibility | Variable - Donor-to-donor variability [2] | High - Genetically uniform but prone to drift [3] |

| Lifespan | Finite - Limited divisions [1] [2] | Infinite - Unlimited divisions [1] |

| Genetic Profile | Diploid, normal karyotype [1] | Often aneuploid/polyploid [4] |

| Experimental Reproducibility | Low to moderate - Higher biological noise [3] [2] | High - Low variability between experiments [3] |

| Scalability | Challenging - Low yield, difficult to expand [3] | Excellent - Easily scalable [3] |

| Ease of Use | Technically complex, time-intensive [2] | Simple to culture [3] |

| Time to Assay | Several weeks post-dissection [3] | Can be assayed within 24-48 hours [3] |

| CRISPR Editing Efficiency | Variable, often lower due to innate defense mechanisms [1] | Generally high and more consistent [1] |

| Key Advantages | Physiological relevance, personalized applications [2] | Practicality, reproducibility, ease of use [1] [3] |

The Biological Fidelity Advantage in CRISPR Research

Physiological Relevance and Therapeutic Predictive Power

Primary cells maintain natural gene expression profiles, metabolic characteristics, and signaling pathways that closely mimic human physiology [2]. This fidelity is particularly valuable in CRISPR research where editing outcomes can be influenced by cellular context, including DNA repair machinery availability and cell cycle status [1] [5]. For therapeutic development, this translates to more predictive models for evaluating gene editing efficacy and safety.

The use of primary cells has revealed critical limitations of immortalized models. For instance, studies demonstrate that findings in immortalized lines frequently fail to translate to human tissue or in vivo models [3]. This translational gap has measurable consequences in drug development, with approximately 97% of CNS-targeted drug candidates entering phase 1 clinical trials never reaching market approval [3].

Applications in Advanced Therapeutic Development

- Immunotherapies: Primary T cells are fundamental for CAR-T cell therapy development, where CRISPR editing enables precise engineering of therapeutic cells [1].

- Disease Modeling: Primary cells from patient biopsies provide personalized systems for studying disease mechanisms and therapeutic options [1].

- 3D Organoid Cultures: Primary cells enable establishment of organoid cultures that closely resemble native tissue architecture and function [1].

- Toxicology and Drug Screening: Primary cells exhibit responses closer to in vivo conditions, providing better insights into compound efficacy and toxicity [2].

Addressing Technical Challenges in Primary Cell CRISPR Editing

Key Obstacles and Strategic Solutions

Table 2: Challenges and solutions for CRISPR editing in primary cells

| Challenge | Impact on CRISPR Editing | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Lifespan | Restricted time window for editing and expansion [1] [2] | Pre-optimize conditions; use early passage cells; consider alternative human models [3] |

| Innate Immune Responses | Degradation of CRISPR components; reduced editing efficiency [1] | Use RNP complexes instead of plasmid DNA [1] |

| Low Transfection Efficiency | Poor delivery of CRISPR machinery [1] | Optimized electroporation protocols; specialized transfection systems [1] |

| Donor Variability | Inconsistent editing outcomes between experiments [2] | Include appropriate controls; pool donors when possible [6] |

| Cell Cycle Effects | Low HDR efficiency due to limited division [1] | Cell cycle synchronization; RNP delivery [1] |

CRISPR-Specific Considerations for Primary Cells

Primary cells present unique molecular challenges for genome editing. Unlike immortalized lines, they have functional DNA repair pathways and intact cell cycle checkpoints, which while more physiologically relevant, can complicate editing strategies [1]. The chromatin structure in primary cells also differs, with heterochromatin regions presenting barriers to CRISPR access [4]. Furthermore, primary immune cells such as T cells have innate mechanisms to resist foreign genetic material, potentially degrading CRISPR components [1].

Essential Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Editing in Primary Human T Cells

This protocol outlines an optimized workstream for achieving high-efficiency CRISPR editing in primary human T cells using ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, based on established methodologies with demonstrated success in hard-to-transfect primary cells [1].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents for primary cell CRISPR editing

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9-NLS [7] | Induces double-strand breaks at target DNA sequences |

| Delivery Systems | 4D-Nucleofector [1], ProDeliverIN CRISPR [7] | Enables efficient RNP delivery into sensitive primary cells |

| Guide RNA Formats | Synthego Research sgRNA [1] | Synthetic sgRNAs with chemical modifications enhance stability and editing efficiency |

| Control Reagents | EditCo's Positive/Negative Controls [6] | Benchmark editing efficiency and distinguish specific from non-specific effects |

| Cell Culture Media | Optimized T-cell media [1] | Supports viability and function of primary T cells post-editing |

| HDR Templates | Single-stranded ODNs [1] | Donor template for precise genome modifications via HDR |

| Analysis Tools | ICE Analysis Tool [4], FlowLogic [7] | Enables quantification of editing efficiency and phenotypic assessment |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Day 1: T Cell Isolation and Activation

- Isolate primary human T cells from PBMCs using Ficoll gradient separation and negative selection beads.

- Count cells and assess viability using Trypan Blue exclusion (target >95% viability).

- Activate T cells using CD3/CD28 activation beads in T-cell media supplemented with IL-2 (50-100 U/mL).

- Culture at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 48-72 hours to promote cell cycle entry, which enhances HDR efficiency [1].

Day 3: RNP Complex Assembly and Electroporation

- RNP Complex Formation: Complex 6 µg of high-quality Cas9 protein with 3 µg of synthetic chemically modified sgRNA (e.g., with 2'-O-methyl 3' phosphorothioate modifications) per 1×10⁶ cells [1]. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest activated T cells, wash with PBS, and resuspend in appropriate electroporation buffer at 1×10⁷ cells/mL.

- Electroporation: Combine 10 µL cell suspension (1×10⁵ cells) with pre-formed RNP complexes. Electroporate using a 4D-Nucleofector system with the appropriate program (typically EH-115 for human T cells) [1].

- Immediate Recovery: Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed culture media and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Days 4-7: Post-Transfection Monitoring and Analysis

- Monitor cell viability daily using flow cytometry with Annexin V/PI staining.

- At 72-96 hours post-electroporation, harvest cells for editing efficiency assessment.

- Editing Efficiency Analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial kits

- Amplify target region by PCR

- Quantify indel formation using T7E1 assay or TIDE analysis

- For precise edits, perform digital droplet PCR or sequencing

- Functional Validation: For CAR-T applications, validate surface expression and cytotoxic function in co-culture assays.

Critical Success Factors

- RNP Over Plasmid: RNP delivery demonstrates higher editing efficiency and reduced toxicity in primary T cells compared to plasmid-based methods [1].

- Cell Cycle Timing: Deliver CRISPR components during active cell division (48-72 hours post-activation) to enhance HDR efficiency [1].

- Control Elements: Include appropriate positive controls (e.g., AAVS1-targeting sgRNAs) and negative controls (non-targeting sgRNAs) to validate editing specificity [6].

Advanced Methodologies: Reporter Systems for Editing Efficiency Quantification

Fluorescent reporter systems provide a high-throughput method for quantifying CRISPR editing efficiency across different repair pathways. The eGFP-to-BFP conversion system enables simultaneous assessment of HDR and NHEJ activity [7].

eGFP-BFP Reporter System Protocol

Reporter Cell Line Generation

- Lentiviral Production: Package the pHAGE2-Ef1a-eGFP-IRES-PuroR plasmid with third-generation packaging plasmids (pMD2.G, pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/pRRE) in HEK293T cells using PEI transfection [7].

- Target Cell Transduction: Transduce your target primary cells with eGFP lentivirus at appropriate MOI (determined empirically).

- Selection and Cloning: Select transduced cells with puromycin (2 µg/mL) for 7-10 days. Isolate single-cell clones and expand for validation.

- Cell Line Validation: Confirm bright, homogeneous eGFP expression via flow cytometry before proceeding with editing experiments.

Editing Efficiency Assessment

- CRISPR Editing: Transfert eGFP-positive cells with RNP complexes targeting the eGFP sequence and an HDR template containing BFP-converting mutations.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: At 48-72 hours post-editing, analyze cells using flow cytometry with appropriate filter sets:

- HDR Efficiency: Calculate percentage of BFP-positive cells (successful HDR)

- NHEJ Efficiency: Calculate percentage of eGFP-negative cells (indel formation)

- Total Editing Efficiency: Combine BFP-positive and eGFP-negative populations

- Data Normalization: Include non-edited controls to account for background fluorescence and calculate normalized editing percentages.

This reporter system enables rapid optimization of delivery methods, RNP formulations, and HDR enhancers without requiring sequencing, significantly accelerating protocol development [7].

Implementing Rigorous Experimental Controls

Appropriate controls are essential for interpreting CRISPR editing outcomes in primary cells, particularly given their inherent biological variability [6].

Table 4: Essential control elements for primary cell CRISPR experiments

| Control Type | Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Controls | Establish editing baseline and assess efficiency across workflows [6] | AAVS1-safe harbor targeting; validated high-efficiency sgRNAs |

| Negative Controls | Distinguish specific editing effects from non-specific changes [6] | Non-targeting sgRNAs; mock electroporation |

| Lethal Controls | Visual confirmation of editing success and delivery optimization [6] | PLK1-targeting sgRNAs inducing apoptosis in 48-72 hours |

| Phenotypic Controls | Benchmark expected phenotypic outcomes [6] | RASA2 knockout in T cells to demonstrate enhanced function |

The integration of primary cells into CRISPR therapeutic development represents a necessary evolution toward more physiologically relevant models. While technical challenges remain, methodological advances in RNP delivery, reporter systems, and protocol standardization are progressively overcoming these hurdles. The future of therapeutic development will likely see increased use of patient-derived primary cells in personalized medicine approaches, combined with advanced engineered models such as ioCells that offer human relevance with improved reproducibility [3]. By adopting the protocols and considerations outlined in this application note, researchers can enhance the predictive validity of their preclinical studies and accelerate the development of safer, more effective CRISPR-based therapies.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, derived from an adaptive immune mechanism in prokaryotes, has emerged as the most efficient and versatile genome engineering tool available to researchers [8]. This technology enables precise manipulation of DNA sequences in living cells through two fundamental components: a guide RNA (gRNA) for target recognition and a CRISPR-associated (Cas9) nuclease for DNA cleavage [8]. The simplicity of reprogramming this system—by merely redesigning the gRNA sequence to match a target of interest—has revolutionized genetic research across diverse organisms and cell types [9]. The core mechanism hinges on creating a targeted DNA double-strand break (DSB) that harnesses the cell's endogenous repair machinery to achieve desired genetic outcomes [8] [10]. This application note details the molecular components, mechanisms, and practical protocols for implementing CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in primary cells, with specific considerations for therapeutic development.

Molecular Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

Guide RNA (gRNA): The Targeting Module

The gRNA is a synthetic chimeric RNA molecule that directs the Cas nuclease to a specific genomic locus through Watson-Crick base pairing [9]. It comprises two structural and functional segments:

- Target-Specific Spacer Sequence: A user-defined 18-20 nucleotide sequence at the 5' end of the gRNA that determines the genomic target through complementarity [8] [9]. The target must be unique within the genome and must lie immediately adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [9].

- scaffold Sequence: A conserved structural component (~80 nucleotides) that binds the Cas9 protein, forming the functional ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [8] [10]. In natural systems, this function is served by two separate RNAs (crRNA and tracrRNA), but most engineering applications utilize a combined single guide RNA (sgRNA) for simplicity [10].

gRNAs can be produced through in vitro transcription or chemical synthesis. Chemically synthesized gRNAs offer advantages for clinical applications, including defined composition, higher purity, and the possibility of incorporating chemical modifications to enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity [10].

Cas9 Nuclease: The Molecular Scissor

The Cas9 protein is a large, multi-domain DNA endonuclease that functions as the executive component of the system. The most widely used variant is SpCas9 from Streptereococcus pyogenes [8]. Its structure consists of two primary lobes:

- Recognition Lobe (REC): Comprising REC1, REC2, and REC3 domains, this lobe is primarily responsible for binding the gRNA scaffold [8] [10].

- Nuclease Lobe (NUC): Contains two nuclease domains and the PAM-interaction site:

The successful formation of the Cas9-gRNA-DNA complex results in a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [8] [9].

Table 1: Engineered Cas9 Variants for Enhanced Specificity and Altered PAM Recognition

| Cas9 Variant | Key Feature | Mechanism of Action | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| eSpCas9(1.1) [9] | Enhanced specificity | Weakened interactions with non-target DNA strand | Reducing off-target effects |

| SpCas9-HF1 [9] | High-fidelity editing | Disrupted interactions with DNA phosphate backbone | Reducing off-target effects |

| HypaCas9 [9] | Increased proofreading | Enhanced discrimination between on-target and off-target sites | Reducing off-target effects |

| xCas9 [9] | PAM flexibility (NG, GAA, GAT) | Mutations in multiple domains | Targeting previously inaccessible sites |

| Cas9 Nickase (Cas9n) [9] | Single-strand break | D10A mutation inactivates RuvC domain (cuts one strand) | Paired nicking for enhanced specificity |

| dead Cas9 (dCas9) [9] | Catalytically inactive | D10A and H840A mutations inactivate both nuclease domains | Gene regulation without cleavage |

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): The Recognition Signal

The PAM is a short (2-6 bp) conserved DNA sequence immediately downstream of the target site that is essential for Cas9 activation [8] [9]. For SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide [9]. PAM recognition triggers local DNA melting, allowing the gRNA to test for complementarity with the target DNA [10]. The absolute requirement for this specific sequence adjacent to the target site is a critical constraint in gRNA design, though engineered Cas9 variants with altered PAM specificities are increasingly mitigating this limitation [9].

Mechanism of Action: From Target Recognition to Double-Strand Break

The process of CRISPR-Cas9 mediated DNA cleavage can be divided into three distinct stages: recognition, cleavage, and repair [8].

Target Recognition and R-loop Formation

The Cas9-gRNA complex searches the genome for compatible PAM sequences through 3D and 1D diffusion [10]. Upon encountering a potential PAM, the complex undergoes a conformational change that triggers unwinding of the adjacent DNA duplex, forming the "seed sequence" (8-10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence) [9]. If the seed sequence matches perfectly, annealing continues in a 3' to 5' direction, displacing the non-complementary DNA strand and forming an R-loop structure where the gRNA is hybridized to the target strand [10]. This R-loop formation induces a second conformational change in Cas9, activating its nuclease domains [10].

DNA Cleavage

Once a stable R-loop is formed, the activated HNH domain cleaves the target DNA strand complementary to the gRNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-target strand [8] [10]. This coordinated cleavage event generates a blunt-ended double-strand break 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [8]. The resulting DSB is highly genotoxic and represents the crucial initiation point for genome editing.

Cellular Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

The cellular DNA damage response machinery detects and repairs the Cas9-induced DSB primarily through two competing pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An efficient but error-prone pathway that directly ligates the broken DNA ends without a template [8] [9]. NHEJ often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site, which can disrupt gene function by creating frameshift mutations or premature stop codons [8] [9]. This pathway is active throughout the cell cycle and is the predominant repair mechanism in most somatic cells [8].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise, template-dependent pathway that uses homologous DNA (typically a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor template) to accurately repair the break [8] [9]. HDR is less efficient than NHEJ and is primarily active in the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [8]. For genome editing applications, researchers can supply a donor DNA template containing desired modifications flanked by homology arms to guide precise gene correction or insertion [7].

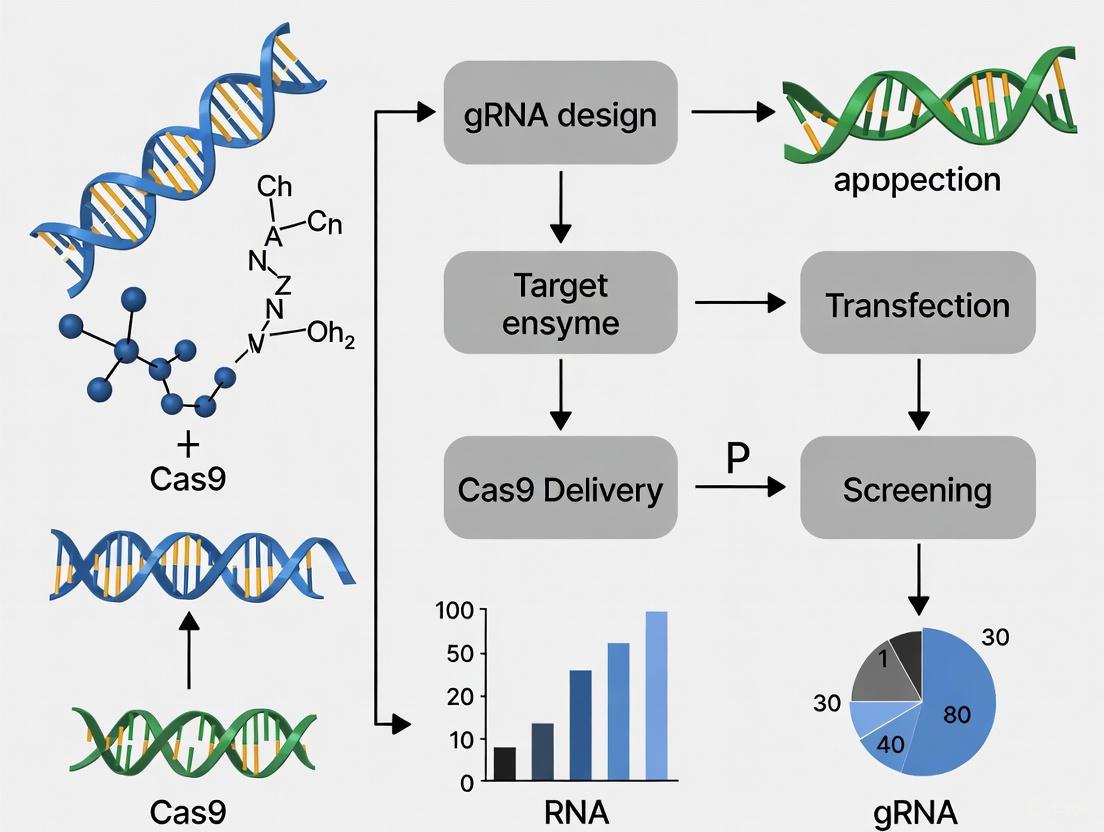

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 target recognition and DNA repair pathways. The process initiates with PAM recognition, proceeds through R-loop formation and Cas9 activation, culminating in DSB formation and subsequent repair via NHEJ or HDR pathways.

Quantitative Analysis of DSB Repair Dynamics

Understanding the kinetics of DSB induction and repair is essential for optimizing editing efficiency. Recent studies using single-molecule sequencing (UMI-DSBseq) have quantified these dynamics in plant protoplasts, revealing that a significant proportion of DSBs are repaired precisely, restoring the original sequence without mutations [11].

Table 2: Quantitative Dynamics of CRISPR-Cas9 Induced DSB Repair in Endogenous Loci

| Target Locus | Maximum Cleavage Efficiency | Indel Accumulation | Precise Repair Rate | Key Kinetic Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhyB2 [11] | 88% | 41% | Up to 70% of all repair events | Highest DSB and indel frequency among targets |

| CRTISO [11] | 64% | 15% | Up to 70% of all repair events | Lower editing efficiency despite high cleavage |

| Psy1 [11] | Not specified | Not specified | Up to 70% of all repair events | High DSB detection with low indel accumulation |

| K562 Cell Line [12] | Not specified | ~98% (mRNA delivery) | Not specified | Microfluidic delivery significantly enhances efficiency |

| K562 Cell Line [12] | Not specified | ~91% (plasmid delivery) | Not specified | Platform outperforms electroporation by 6.5-fold |

The data reveals that indel accumulation is determined by the combined effect of DSB induction rate, processing of broken ends, and the competition between precise versus error-prone repair [11]. The high rate of precise repair highlights a fundamental challenge in achieving high editing efficiencies, as successfully cleaved targets may be restored to their original sequence rather than becoming mutated [11].

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

Protocol 1: Fluorescent Reporter Assay for Editing Efficiency

This protocol utilizes an eGFP to BFP conversion system to simultaneously quantify HDR and NHEJ outcomes in live cells [7].

Materials:

- eGFP-positive HEK293T cells (or other relevant cell line)

- SpCas9 protein with Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS)

- sgRNA targeting eGFP locus: GCUGAAGCACUGCACGCCGU [7]

- HDR template ssODN for BFP conversion [7]

- Transfection reagent (e.g., Polyethylenimine or ProDeliverIN CRISPR)

- Flow cytometer with 488nm (eGFP) and 405nm (BFP) lasers

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture eGFP-positive HEK293T cells in complete DMEM with 10% FBS. Passage cells every 3-4 days to maintain 50-80% confluency [7].

- RNP Complex Formation: Complex 5 µg SpCas9-NLS with 2 µL of 100 µM sgRNA in opti-MEM medium. Incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature [7].

- Transfection: For HDR experiments, add 2 µL of 100 µM ssODN HDR template to the RNP complex. Mix with transfection reagent according to manufacturer's protocol and add to cells [7].

- Incubation and Analysis: Harvest cells 72 hours post-transfection. Analyze by flow cytometry using 488nm excitation/507nm emission for eGFP and 405nm excitation/448nm emission for BFP [7].

Data Interpretation:

- BFP-positive cells indicate successful HDR

- eGFP-negative/BFP-negative cells indicate NHEJ-mediated knockout

- Remaining eGFP-positive cells indicate no editing or precise repair

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Delivery for Primary Cells

This protocol describes a droplet cell pincher (DCP) platform for highly efficient RNP delivery in hard-to-transfect cells, including primary cells [12].

Materials:

- DCP microfluidic device

- Cell suspension (K562 cells or primary cells of interest)

- SpCas9 RNP complexes

- Oil for droplet generation

- Syringe pumps for precise flow control

Procedure:

- RNP Preparation: Pre-complex SpCas9 protein with sgRNA at molar ratio of 1:1.2 in appropriate buffer. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature [12].

- Sample Loading: Mix cell suspension with RNP complexes. Load into syringe along with droplet generation oil [12].

- Microfluidic Processing: Pump cell/RNP mixture and oil independently into microfluidic flow-focusing geometry to generate uniform droplets. Use additional oil sheath flow to accelerate droplets through a single constriction [12].

- Cell Collection and Culture: Collect processed cells and culture under standard conditions. Analyze editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-processing [12].

Key Advantages:

- Achieves ~98% delivery efficiency for mRNA and ~91% for plasmids [12]

- Outperforms electroporation by 6.5-fold for knockouts and 3.8-fold for knock-ins [12]

- Maintains high cell viability compared to electroporation [12]

Protocol 3: Assessing On-Target Editing Efficiency

Multiple methods exist for quantifying CRISPR editing efficiency, each with distinct advantages and limitations [13].

Table 3: Comparison of Methods for Assessing On-Target Editing Efficiency

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) [13] | Mismatch cleavage of heteroduplex DNA | Semi-quantitative | Medium | Rapid screening of editing activity |

| TIDE [13] | Decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces | Quantitative | High | Quick assessment of indel patterns |

| ICE [13] | Algorithmic analysis of sequencing chromatograms | Quantitative | High | Detailed indel characterization |

| ddPCR [13] | Differential fluorescent probe detection | Highly quantitative | Medium | Precise quantification of specific edits |

| Fluorescent Reporters [7] [13] | Live-cell detection of functional edits | Quantitative, cell-specific | Very High | Real-time tracking and sorting of edited cells |

Diagram 2: CRISPR-Cas9 experimental workflow. The process begins with target selection and proceeds through delivery method optimization, culminating in validation through complementary analytical approaches tailored to specific experimental needs.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for Primary Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Proteins [14] [7] | SpCas9-NLS, High-fidelity variants | DNA cleavage at target site | RNP format preferred for reduced off-target effects |

| Guide RNAs [14] [7] | Chemically synthesized sgRNA, crRNA:tracrRNA duplex | Target recognition and Cas9 binding | Chemical modifications enhance stability |

| Delivery Tools [12] [7] | Microfluidic DCP, Electroporation, Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Intracellular delivery of editing components | Microfluidic shows superior efficiency for hard-to-transfect cells |

| Editing Reporters [7] [13] | eGFP-BFP system, ddPCR assays | Quantification of editing outcomes | Fluorescent reporters enable live-cell tracking and sorting |

| Validation Tools [13] | T7EI, TIDE, ICE, ddPCR | Assessment of on-target efficiency | Method selection depends on required precision and throughput |

The core CRISPR-Cas9 machinery—comprising the guide RNA, Cas nuclease, and the resulting double-strand break—represents a powerful and precise system for genome engineering. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of target recognition, cleavage, and repair pathway choices is essential for designing effective editing strategies. The protocols and analytical methods detailed herein provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing CRISPR-Cas9 in primary cells, with particular attention to quantitative assessment of editing outcomes. As the field advances, continued optimization of delivery methods, reagent quality, and analytical techniques will further enhance the precision and therapeutic potential of this transformative technology.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genome engineering by providing researchers with a precise and efficient method for making targeted DNA modifications in living cells. This technology originates from a bacterial adaptive immune system and has been repurposed as a powerful genome editing tool [15]. The system operates through a simple yet powerful mechanism: a Cas nuclease, directed by a guide RNA (gRNA), recognizes a target DNA sequence via Watson-Crick base pairing and induces a double-strand break (DSB) [16]. The Cas9 enzyme forms a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with a guide RNA molecule, the sequence of which can target specific genes using approximately 20 nucleotides of homology to the genomic target [7].

Following DSB induction, cellular DNA repair mechanisms are activated, primarily through two competing pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR) [15]. The balance between these pathways presents both challenges and opportunities for researchers seeking to achieve precise genome modifications. NHEJ is an error-prone repair mechanism that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site, which can be exploited for gene knockouts [16]. In contrast, HDR is a precise repair mechanism that uses homologous donor DNA to repair DNA damage, enabling specific nucleotide changes or insertion of larger DNA fragments [15] [17]. The competition between these pathways is a critical determinant of editing outcomes, with NHEJ typically dominating in most cell types, especially non-dividing cells [15].

This application note provides detailed methodologies for optimizing the balance between error-prone NHEJ and precise HDR to enhance knock-in efficiency in primary cells, with a focus on protocols, quantitative assessments, and practical implementation strategies for research and therapeutic development.

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) Pathway

NHEJ is the predominant DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells and operates throughout the cell cycle [15]. This pathway begins with the activation of the Ku protein complex, a heterodimeric protein composed of approximately 70- and 80-kDa subunits (Ku70 and Ku80), which recognizes and wraps the end of the broken DNA strand [15]. The NHEJ process involves three principal sub-pathways:

- Blunt-end ligation-dependent Ku-XRCC4-DNA ligase IV sub-pathway: The Ku protein promotes the binding of X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 4 (XRCC4) and DNA ligase IV to the DNA ends, catalyzing the reconstitution of broken double-strand DNA [15].

- Nuclease-dependent sub-pathway: The Ku complex recruits DNA-dependent protein kinases (DNA-PKcs) to bind to DNA ends, forming stable enzymatically active complexes that interact with and activate the endonuclease activity of Artemis [15].

- Polymerase-dependent sub-pathway: Polymerase Pol μ and Pol λ are recruited to the DNA ends via interaction with the Ku-DNA complex, promoting the formation of terminal microhomology to stimulate the joining of two mismatched 3' overhangs [15].

While NHEJ is traditionally considered error-prone, recent evidence suggests that repair of Cas9-induced DSBs is inherently accurate, with accurate NHEJ accounting for approximately 50% of NHEJ events in the repair of two adjacent DSBs induced by paired Cas9-gRNAs [18]. This discovery has important implications for designing precise genome editing strategies.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Pathway

HDR is a precise repair mechanism that requires a homologous DNA template to guide repair. This pathway is primarily active in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when a sister chromatid is available [15]. In the context of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing, researchers can hijack this natural process by providing an exogenous donor template containing the desired modifications flanked by homology arms complementary to the sequences surrounding the DSB.

The HDR process involves:

- End resection: The 5' ends at the break site are resected to generate 3' single-stranded DNA overhangs

- Strand invasion: The 3' overhangs invade the homologous donor template

- DNA synthesis: DNA polymerase synthesizes new DNA using the donor template as a guide

- Resolution: The resulting DNA structures are resolved and ligated

HDR is particularly valuable for introducing specific nucleotide changes, inserting reporter genes, or creating precise gene fusions [15]. However, its efficiency is generally lower than NHEJ, especially in non-dividing cells, presenting a significant challenge for applications requiring precise edits.

Competing and Alternative Repair Pathways

Beyond classical NHEJ and HDR, cells possess additional repair mechanisms that can influence genome editing outcomes:

- Microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ): An error-prone pathway that utilizes microhomologous sequences (5-25 bp) for end joining, resulting in deletions flanked by microhomology regions [10]

- Single-strand annealing (SSA): Requires longer homologous sequences (>30 bp) and often results in significant deletions [10]

These alternative pathways further complicate the landscape of DNA repair and must be considered when designing genome editing strategies. The following diagram illustrates the competitive relationships between these repair pathways:

Quantitative Analysis of HDR and NHEJ Efficiencies

Understanding the quantitative relationship between HDR and NHEJ is essential for designing effective genome editing experiments. Research has demonstrated that the HDR/NHEJ ratio is highly dependent on multiple factors, including gene locus, nuclease platform, and cell type [17].

Systematic Comparison Across Platforms and Loci

A comprehensive study using a novel digital PCR-based assay to simultaneously detect HDR and NHEJ events revealed surprising insights about their relative frequencies [17]. Contrary to the widely held belief that NHEJ generally occurs more often than HDR, researchers found that more HDR than NHEJ was induced under multiple conditions. The quantitative data from this systematic analysis are summarized in the table below:

Table 1: HDR and NHEJ Efficiencies Across Different Nuclease Platforms and Gene Loci in HEK293T Cells

| Nuclease Platform | Gene Locus | HDR Efficiency (%) | NHEJ Efficiency (%) | HDR/NHEJ Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype Cas9 | RBM20 | 24.5 ± 1.7 | 41.6 ± 2.3 | 0.59 |

| Wildtype Cas9 | GRN | 32.8 ± 3.9 | 28.5 ± 3.8 | 1.15 |

| Cas9-D10A Nickase | RBM20 | 13.3 ± 1.6 | 18.2 ± 1.6 | 0.73 |

| Cas9-D10A Nickase | GRN | 22.5 ± 2.9 | 15.3 ± 1.5 | 1.47 |

| FokI-dCas9 | RBM20 | 22.0 ± 1.7 | 32.5 ± 2.4 | 0.68 |

| FokI-dCas9 | GRN | 28.3 ± 2.8 | 21.7 ± 2.1 | 1.30 |

| TALEN | RBM20 | 19.7 ± 1.7 | 27.3 ± 2.2 | 0.72 |

| TALEN | GRN | 26.5 ± 3.3 | 18.3 ± 2.1 | 1.45 |

This data demonstrates that the GRN locus consistently shows higher HDR/NHEJ ratios compared to RBM20 across all nuclease platforms, highlighting the significant influence of local genomic context on repair pathway choices [17].

Cell Type-Dependent Variations

The same study also revealed substantial differences in editing efficiencies across cell types, emphasizing the need for cell-specific optimization:

Table 2: Cell Type Variations in HDR and NHEJ Efficiencies for Wildtype Cas9

| Cell Type | Gene Locus | HDR Efficiency (%) | NHEJ Efficiency (%) | HDR/NHEJ Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293T | RBM20 | 24.5 ± 1.7 | 41.6 ± 2.3 | 0.59 |

| HEK293T | GRN | 32.8 ± 3.9 | 28.5 ± 3.8 | 1.15 |

| HeLa | RBM20 | 19.3 ± 1.8 | 30.6 ± 2.6 | 0.63 |

| HeLa | GRN | 26.9 ± 3.1 | 21.4 ± 2.4 | 1.26 |

| Human iPSCs | RBM20 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 15.3 ± 1.8 | 0.57 |

| Human iPSCs | GRN | 12.5 ± 1.9 | 9.8 ± 1.4 | 1.28 |

The consistently lower absolute editing efficiencies in iPSCs highlight the particular challenge of achieving precise edits in therapeutically relevant primary cell types [17].

Advanced Strategies for Enhancing HDR Efficiency

Nuclear Localization Signal Engineering

Recent advances in nuclear localization signal (NLS) engineering have demonstrated significant improvements in editing efficiency, particularly for therapeutic applications. Researchers from the Innovative Genomics Institute developed a novel approach using hairpin internal nuclear localization signal sequences (hiNLS) installed at selected sites within the backbone of CRISPR-Cas9, contrasting with the widely adopted strategy of incorporating terminally fused NLS sequences [19].

This hiNLS strategy enhanced knockout efficiencies for key therapeutic targets in human primary T cells, including beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) and T cell receptor alpha chain (TRAC) [19]. The approach is particularly valuable for ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery, which has a 1-2 day half-life and requires rapid nuclear localization to induce editing before metabolic degradation. The hiNLS constructs can be produced with high purity and yield compared to their terminally fused counterparts, supporting manufacturing scalability for clinical applications [19].

HDR Enhancement Through NHEJ Inhibition

Several chemical and genetic approaches have been developed to shift the balance from NHEJ toward HDR by inhibiting key components of the NHEJ pathway:

- DNA-PKcs inhibitors: Compounds such as AZD7648 can suppress NHEJ and promote HDR, though recent evidence shows they may exacerbate genomic aberrations, including kilobase- and megabase-scale deletions [16]

- 53BP1 inhibition: Transient inhibition of 53BP1 has been shown to enhance HDR without increasing translocation frequencies [16]

- Cell cycle synchronization: Restricting editing to S/G2 phases when HDR is more active [15]

- p53 suppression: Transient inhibition of p53 can reduce large chromosomal aberrations, though concerns about oncogenic transformation exist [16]

Recent findings by Cullot et al. revealed that using the DNA-PKcs inhibitor AZD7648 significantly increased frequencies of kilobase- and megabase-scale deletions as well as chromosomal arm losses across multiple human cell types and loci [16]. This highlights the importance of carefully evaluating the safety implications of HDR-enhancing strategies.

Optimized Delivery Systems for Primary Cells

Efficient delivery of editing components to primary cells remains a significant challenge. Conventional electroporation platforms often require high cell input (hundreds of thousands to millions of cells per condition), limiting their utility with rare or patient-derived populations [20]. Recent advances in digital microfluidics (DMF) electroporation have enabled high-efficiency genome engineering with substantially reduced cell inputs.

A next-generation DMF electroporation platform supporting 48 independently programmable reaction sites demonstrated efficient delivery of various cargo, with high rates of transfection, gene knockout via NHEJ, and precise knock-in through HDR using as few as 3,000 primary human cells per condition [20]. This technology enables high-throughput, low-input genome engineering and is particularly valuable for working with precious primary cell samples.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Editing Outcomes

eGFP-to-BFP Conversion Assay for High-Throughput Screening

A robust protocol for rapidly screening CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing outcomes utilizes a fluorescent reporter system based on enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) to blue fluorescent protein (BFP) conversion [7]. This system enables simultaneous quantification of HDR and NHEJ events through straightforward fluorescence measurements.

Table 3: Key Reagents for eGFP-to-BFP Conversion Assay

| Reagent | Source | Identifier/Sequence | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9-NLS | Walther et al. | N/A | CRISPR nuclease with nuclear localization |

| pHAGE2-Ef1a-eGFP-IRES-PuroR | De Jong et al. | N/A | Lentiviral vector for eGFP expression |

| Optimized BFP mutation template | Merck | caagctgcccgtgccctggcccaccctcgtgaccaccctgAGCCACggcgtgcagtgcttcagccgctaccccgaccacatgaagc | HDR template for eGFP to BFP conversion |

| sgRNA against eGFP locus | Merck | GCUGAAGCACUGCACGCCGU | Targets eGFP for Cas9 cleavage |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Polysciences | 23966 | Transfection reagent |

| ProDeliverIN CRISPR | OZ Biosciences | PIC0500 | Alternative delivery reagent |

Protocol Steps:

Generation of eGFP-positive cell lines:

- Produce lentiviral particles using pHAGE2-Ef1a-eGFP-IRES-PuroR and packaging plasmids (pMD2.G, pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/pRRE)

- Transduce target cells with lentivirus and select with puromycin (2 μg/mL) for 7 days

- Confirm eGFP expression by fluorescence microscopy or FACS

Transfection of gene editing reagents:

- Seed eGFP-positive cells in appropriate culture vessels

- Transfect with SpCas9-NLS and sgRNA complexed with delivery reagent (PEI or ProDeliverIN CRISPR)

- Include HDR template (BFP mutation template) for HDR experiments

Post-transfection analysis:

- Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-transfection

- Analyze by flow cytometry to quantify eGFP-positive (unedited), BFP-positive (HDR-edited), and double-negative (NHEJ-edited) populations

- Calculate HDR and NHEJ efficiencies as percentages of total cells

This protocol enables rapid, high-throughput assessment of gene editing techniques and is particularly valuable for screening formulations for CRISPR-Cas9 delivery and functional screening of CRISPR-enhancing therapies [7].

Digital PCR for Simultaneous HDR and NHEJ Quantification

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) provides a highly sensitive method for simultaneously quantifying HDR and NHEJ events at endogenous loci without the need for fluorescent reporters [17]. This approach enables precise measurement of editing outcomes across multiple conditions and cell types.

Protocol Steps:

Design of ddPCR assays:

- Design amplicons with predicted nuclease cut sites positioned mid-amplicon, with 75-125 base pairs flanking either side

- Position at least one primer outside the donor molecule sequence to ensure quantification of integrated edits

- Design reference probes and primers distant from the cut site to avoid loss of binding sites

- Empirically determine optimal annealing temperature with a temperature gradient

Sample preparation:

- Extract genomic DNA from edited cells 3-6 days post-transfection

- Prepare ddPCR reactions with target-specific probes and reference probes

Data analysis:

- Analyze ddPCR data to quantify absolute numbers of HDR and NHEJ events

- Normalize to reference signals to account for variations in DNA input

- Calculate HDR and NHEJ efficiencies as percentages of total alleles

This method can detect one HDR or NHEJ event out of 1,000 copies of the genome, providing exceptional sensitivity for evaluating editing outcomes [17].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Genome Editing

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | SpCas9-NLS, Cas9-D10A nickase, FokI-dCas9 | Induce targeted DNA breaks | hiNLS Cas9 variants enhance nuclear import [19] |

| Delivery Tools | Polyethylenimine (PEI), ProDeliverIN CRISPR, Digital microfluidics electroporation | Deliver editing components to cells | DMF enables high-efficiency editing with 3,000-10,000 cells [20] |

| HDR Enhancers | 53BP1 inhibitors, Cell cycle synchronizers, Modified donor templates | Shift repair balance toward HDR | DNA-PKcs inhibitors may increase structural variations [16] |

| Reporter Systems | eGFP-BFP conversion system, ddPCR assays | Quantify editing outcomes | eGFP-BFP enables high-throughput screening [7] |

| Analysis Tools | FlowLogic, GraphPad Prism, CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS | Data analysis and validation | CAST-Seq detects structural variations [16] |

Safety Considerations and Clinical Implications

As CRISPR-based therapies progress toward clinical application, understanding and mitigating risks associated with genome editing becomes increasingly important. Recent studies have revealed that beyond well-documented concerns of off-target mutagenesis, more pressing challenges include large structural variations (SVs), such as chromosomal translocations and megabase-scale deletions [16].

These undervalued genomic alterations raise substantial safety concerns for clinical translation. In the context of the first approved CRISPR therapy, exa-cel (Casgevy), frequent occurrence of large kilobase-scale deletions upon BCL11A editing in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) warrants close scrutiny [16]. Furthermore, aberrant BCL11A expression has been associated with impaired lymphoid development, reduced engraftment potential, and cellular senescence [16].

The following workflow diagram illustrates an integrated approach for achieving precise knock-ins while monitoring for potential structural variations:

Balancing error-prone NHEJ with precise HDR for efficient knock-ins requires a multifaceted approach that considers cell type, delivery method, nuclease architecture, and cell state. The protocols and data presented here provide a framework for optimizing precise genome editing in primary cells, with particular relevance for therapeutic development.

Future directions in the field include:

- Advanced editor engineering: Continued development of optimized Cas variants with enhanced specificity and nuclear localization properties

- Temporal control: Refined methods for controlling the timing and duration of nuclease activity to align with optimal cell states for HDR

- Comprehensive safety profiling: Implementation of more sophisticated methods for detecting structural variations and other unintended consequences

- Alternative precise editing systems: Exploration of base editing and prime editing technologies that may offer improved safety profiles

As the field continues to evolve, the balance between editing efficiency and safety will remain paramount, particularly for clinical applications. The strategies outlined here provide a foundation for achieving this balance while maximizing the potential of CRISPR-based genome editing for research and therapeutic purposes.

Primary cells, isolated directly from living tissue, provide highly biologically relevant models for CRISPR research as they more accurately represent natural physiology compared to immortalized cell lines [21]. However, their inherent characteristics pose significant barriers to efficient gene editing. These cells are typically quiescent (non-dividing), exhibit greater sensitivity to manipulation, and possess inherently low transfection efficiency compared to transformed cell lines [21] [22]. Furthermore, primary cells have limited expansion capacity, providing fewer opportunities for CRISPR components to enter the nucleus during cell division [21]. These biological constraints create a complex challenge landscape that requires specialized protocols to overcome.

Core Challenges in CRISPR Editing of Primary Cells

Cellular Quiescence and DNA Repair Bias

The non-dividing nature of primary cells fundamentally alters DNA repair pathway activity, creating a major barrier to precise genome editing.

Repair Pathway Imbalance: Quiescent primary cells, including neurons, T cells, and hematopoietic stem cells, predominantly utilize the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway throughout the cell cycle, while homology-directed repair (HDR) is largely restricted to specific cell cycle phases (S/G2/M) [22]. This creates a natural bias toward error-prone NHEJ rather than precise HDR, which is particularly problematic for knock-in strategies requiring precise template integration.

Prolonged Repair Kinetics: Research comparing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to iPSC-derived neurons reveals that Cas9-induced indels accumulate much more slowly in postmitotic cells, continuing to increase for up to 16 days post-delivery compared to plateauing within days in dividing cells [22]. This extended repair timeline has important implications for experimental design and analysis timing.

Unique Repair Mechanisms: Postmitotic cells upregulate non-canonical DNA repair factors and employ different DSB repair pathways than dividing cells, yielding different CRISPR editing outcomes with a narrower distribution of indel types [22].

Table 1: DNA Repair Characteristics in Dividing vs. Primary Cells

| Parameter | Dividing Cells | Primary/Quiescent Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant Repair Pathway | Both NHEJ and HDR active | NHEJ predominant |

| MMEJ Activity | Higher | Lower |

| Repair Timecourse | Indels plateau within days | Indels accumulate over weeks |

| Indel Distribution | Broad range | Narrow distribution |

| HDR Efficiency | Higher | Significantly lower |

Sensitivity to Manipulation

Primary cells demonstrate heightened sensitivity to transfection methods and CRISPR component delivery, requiring carefully optimized conditions to maintain viability and function.

Physical Stress Sensitivity: Methods like electroporation can cause significant toxicity in sensitive primary cell types such as T cells and hematopoietic stem cells [23]. Optimization of electrical parameters, buffer composition, and cell handling is essential for maintaining viability.

Immunogenic Reactions: Primary cells may mount stronger immune responses to delivery vectors and bacterial-derived CRISPR components compared to immortalized lines [23]. Viral vectors can trigger inflammatory pathways, while prolonged Cas9 expression may increase immune recognition.

P53-Mediated Stress Responses: DNA damage from CRISPR editing can activate p53 pathways, potentially triggering apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, or delayed proliferation in primary cells [16]. Transient p53 suppression has been explored but raises oncogenic concerns given p53's critical tumor suppressor role [16].

Low Transfection Efficiency

Achieving efficient delivery of CRISPR components represents perhaps the most significant technical challenge in primary cell editing.

Barrier Penetration: Primary cells present multiple cellular barriers including plasma membranes and, for nuclear delivery, nuclear envelopes [21]. Unlike dividing cells where nuclear breakdown during mitosis facilitates access, quiescent cells maintain intact nuclear membranes.

Delivery Method Limitations: Viral vectors face size constraints (particularly AAV's ~4.7 kb capacity) that complicate delivery of large Cas9 orthologs [23]. Chemical methods like lipofection often show reduced efficiency in primary cells compared to cell lines [21].

Format Considerations: The format of CRISPR components significantly impacts efficiency. Pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes enable rapid editing without requiring nuclear entry for transcription/translation, making them particularly valuable for primary cells [21].

Table 2: Transfection Efficiency Across Primary Cell Types

| Cell Type | Recommended Method | Relative Efficiency | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary T Cells | Nucleofection, Viral Transduction | Moderate-High | Activation state affects efficiency |

| Hematopoietic Stem Cells | Nucleofection, Electroporation | Moderate | Toxicity concerns critical |

| Neurons | Virus-Like Particles (VLPs), Specialized reagents | Low-Moderate | Extreme sensitivity to manipulation |

| Primary B Cells | Electroporation | Moderate | Difficult to transfert, low viability |

| Epithelial Cells | Lipofection, Electroporation | Variable | Highly donor-dependent |

Advanced Strategies and Protocol Solutions

Enhancing HDR Efficiency in Quiescent Cells

Given the natural HDR deficiency in non-dividing primary cells, specific interventions are required for precise editing applications.

HDR Template Optimization: For short insertions (<100 bp) using single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), homology arms of 30-60 nucleotides are recommended. For larger insertions, double-stranded templates with 200-500 bp homology arms show superior efficiency [24]. Strategic placement of edits within 5-10 bp of the cut site minimizes strand preference effects [24].

Small Molecule Enhancement: Small molecule inhibitors targeting key NHEJ components can shift repair toward HDR. Compounds such as nedisertib (DNA-PKcs inhibitor) and other proprietary NHEJ inhibitors are commercially available [24]. However, recent evidence indicates that DNA-PKcs inhibition may exacerbate genomic aberrations including kilobase- and megabase-scale deletions, requiring careful risk-benefit analysis [16].

Cell Cycle Synchronization: Though challenging in truly quiescent cells, mild stimulation protocols can sometimes induce limited cycling in certain primary cell types (e.g., T cells), creating a transient window of HDR competence [24].

Specialized Delivery Methods for Primary Cells

Advanced delivery strategies have been developed specifically to address primary cell limitations.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery: Electroporation of pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA complexes enables rapid degradation and reduced off-target effects while bypassing transcription/translation requirements [21]. This approach is particularly valuable for sensitive primary cells where transient editing is desirable.

Virus-Like Particles (VLPs): Engineered VLPs pseudotyped with VSVG and/or BaEVRless (BRL) envelopes can achieve up to 97% delivery efficiency in challenging primary cells like neurons while maintaining cell viability [22]. VLPs deliver active Cas9 RNP complexes rather than nucleic acids, combining high efficiency with transient activity.

Nucleofection Technology: This electroporation-based method optimized for nuclear delivery uses cell-type specific reagents and electrical parameters. Pre-optimized programs exist for many primary cell types, significantly improving efficiency over standard electroporation [21].

Comprehensive Protocol for Primary T Cell Editing

The following detailed protocol demonstrates optimized procedures for challenging primary cell types, incorporating solutions to the core challenges discussed.

Pre-editing Preparation

Cell Quality Assessment: Isolate T cells from fresh blood samples using Ficoll gradient separation or leukapheresis products. Ensure viability >95% by trypan blue exclusion. Use cells within 6 hours of isolation for optimal results.

CRISPR Component Preparation: Design sgRNAs with computational tools (CRISPick, CHOPCHOP) and synthesize using high-quality vendors. For RNP complex formation, combine 60 pmol Cas9 protein with 120 pmol sgRNA in nuclease-free buffer, incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes to allow complex formation.

HDR Template Design: For knock-in applications, design single-stranded DNA templates with 60-90 nt homology arms. Incorporate silent mutations in PAM-distal regions to prevent re-cutting and enable tracking. Include purification tags (FLAG, HIS) when appropriate for downstream validation.

Transfection Procedure

Equipment and Reagents:

- Nucleofector Device (Lonza) with appropriate primary T cell kit

- Pre-assembled Cas9 RNP complexes

- HDR template (ssODN or dsDNA)

- Optional: HDR enhancer compounds

Step-by-Step Process:

- Wash 1-2×10^6 T cells in PBS, resuspend in 100 μl nucleofection solution

- Mix cells with RNP complexes (final concentration 2-6 μM) and HDR template (100-500 nM)

- Transfer to certified cuvette, apply pre-optimized program (EO-115 for human T cells)

- Immediately add pre-warmed complete media (RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS + IL-2 100 U/ml)

- Transfer to 96-well plate, incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂

- For HDR enhancement, add small molecule inhibitors (e.g., 1 μM nedisertib) 2 hours post-transfection for 24-48 hours duration

Post-transfection Analysis

Efficiency Assessment: At 48-72 hours post-editing, analyze indel efficiency by T7E1 assay or TIDE analysis. For knock-ins, use flow cytometry for surface markers or PCR-based validation for internal tags.

Viability Monitoring: Measure cell viability at 24-hour intervals using flow cytometry with Annexin V/7-AAD staining. Expect 40-70% viability depending on cell donor and editing extent.

Functional Validation: For engineered T cells (e.g., CAR-T), perform functional assays including cytokine secretion, cytotoxicity, and proliferation in response to target antigens at 7-14 days post-editing.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Primary Cell CRISPR Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleofection Systems | Lonza 4D-Nucleofector | Optimized electroporation for primary cells |

| HDR Enhancers | Nedisertib (M9831), proprietary compounds | Shift repair balance from NHEJ to HDR |

| CRISPR Formats | Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease 3NLS | High-performance Cas9 with nuclear localization |

| Cell Culture Supplements | IL-2, IL-7, IL-15 | Maintain viability and function post-editing |

| Viability Enhancers | Rho kinase inhibitor (Y-27632) | Reduce apoptosis in sensitive primary cells |

| Detection Tools | Alt-R Genome Editing Detection Kit | T7E1 mismatch detection for editing efficiency |

DNA Repair Pathway Engineering

Understanding and manipulating DNA repair pathways is essential for improving editing outcomes in primary cells.

The challenges of quiescence, sensitivity, and low transfection efficiency in primary cultures remain significant but surmountable barriers in CRISPR research. The protocols and strategies outlined here provide a framework for overcoming these limitations through specialized delivery methods, repair pathway manipulation, and optimized culture conditions. As the field advances, emerging technologies including novel nanoparticle systems, engineered Cas variants with reduced size and improved specificity, and small molecules that temporarily modulate DNA repair pathways show promise for further enhancing primary cell editing [23] [25]. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches is beginning to refine gRNA design and outcome prediction, potentially overcoming some limitations of primary cell editing through improved computational planning [23]. By addressing these fundamental biological challenges with tailored experimental approaches, researchers can increasingly leverage the full potential of primary cell systems for both basic research and therapeutic development.

The selection of an appropriate gene editing strategy is a critical first step in designing robust CRISPR experiments in primary cells. These cells, which are isolated directly from living tissue, present unique challenges including limited expansion capability, heightened sensitivity to in vitro manipulation, and inherent resistance to foreign genetic material compared to immortalized cell lines [1]. The choice between generating a loss-of-function mutation via knock-out or achieving precise sequence alteration via knock-in or base editing must align with both the experimental objectives and the biological constraints of the primary cell system.

This application note provides a structured framework for selecting and implementing four principal CRISPR-based editing approaches in primary cells: knock-outs, knock-ins, base editing, and prime editing. We present optimized protocols, quantitative efficiency comparisons, and practical reagent guidelines to enable researchers to navigate the technical complexities of primary cell gene editing for both basic research and therapeutic development.

Editing Modalities: Mechanisms and Applications

Knock-outs via Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Mechanism and Applications: CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) are predominantly repaired via the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the target site [1] [26]. When these indels occur within a protein-coding exon, they can disrupt the reading frame and lead to premature stop codons, effectively generating a gene knockout. This approach is particularly valuable for loss-of-function studies, investigating essential genes in signaling pathways, and functional genomic screens in diverse primary cell types including T cells, fibroblasts, and hematopoietic stem cells [1].

The primary advantage of NHEJ-mediated knockout lies in its relatively high efficiency, as NHEJ is active throughout all phases of the cell cycle and does not require a template DNA [27]. This makes it particularly suitable for post-mitotic primary cells or those with limited proliferative capacity. However, the stochastic nature of indel formation can result in a heterogeneous mixture of mutations, necessitating careful validation at both the genomic and protein levels [28].

Knock-ins via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Mechanism and Applications: In contrast to NHEJ, homology-directed repair (HDR) utilizes a donor DNA template to facilitate precise gene editing at the target locus [1] [26]. This pathway enables researchers to insert specific DNA sequences, such as reporter genes, epitope tags, or disease-relevant mutations, into the genome of primary cells. knock-ins are especially powerful for studying protein localization and function, modeling genetic diseases, and engineering therapeutic cell products like CAR-T cells [1] [27].

A significant challenge with HDR-based approaches is their inherently lower efficiency compared to NHEJ, particularly in primary cells which often reside in quiescent states [27]. HDR occurs preferentially during the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, where sister chromatids are available as natural repair templates [1]. This cell cycle dependency makes HDR less efficient in non-dividing or slowly proliferating primary cell populations, requiring specialized strategies to enhance knock-in efficiency.

Base Editing

Mechanism and Applications: Base editors represent a groundbreaking advancement in precision gene editing by enabling direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without introducing DSBs [29] [30]. These fusion proteins combine a catalytically impaired Cas protein (nickase) with a deaminase enzyme, creating a system that can precisely alter single nucleotides. Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) convert C•G to T•A base pairs, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) perform A•T to G•C conversions [29]. Together, these editors can theoretically correct approximately 95% of known pathogenic point mutations cataloged in ClinVar [30].

The DSB-free nature of base editing eliminates the formation of indels and reduces p53-driven stress responses, making it particularly advantageous for therapeutic applications in primary cells [30]. However, base editors are constrained by specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) requirements and have a defined activity window within the target region, which can limit targeting flexibility [29]. Recent concerns about RNA off-target editing have prompted the development of engineered ABE variants with minimized RNA editing activity while maintaining high on-target efficiency [31].

Prime Editing

Mechanism and Applications: Prime editing represents the most recent innovation in precision genome editing, offering even greater versatility than base editing [29]. This system uses a catalytically impaired Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme and is programmed with a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). The pegRNA both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit, serving as a template for the reverse transcriptase [31].

Prime editing can accomplish all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, in addition to small insertions and deletions, without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates [29]. This versatility makes it particularly valuable for correcting complex mutations and introducing specific sequence modifications in primary cells that are difficult to transfer with large DNA templates. Recent advances, such as the proPE system, have demonstrated enhanced editing efficiency through the use of a second non-cleaving sgRNA to improve targeting precision [31].

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Editing Modalities for Primary Cells

| Editing Type | Mechanism | Key Applications | Efficiency Range | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knock-out (NHEJ) | DSB repair without template | Gene disruption, functional screens | 70-93% [28] | High efficiency, works in non-dividing cells | Introduces random indels |

| Knock-in (HDR) | DSB repair with donor template | Precise insertions, reporter tags, disease modeling | 20-40% [1] [27] | Precise sequence insertion | Low efficiency, requires cell division |

| Base Editing | Direct chemical base conversion | Point mutation correction, SNP introduction | Varies by system | No DSBs, high precision | Limited by PAM and editing window |

| Prime Editing | Reverse transcription from pegRNA | All 12 base conversions, small edits | ~35% (reported in iPSC-cardiomyocytes) [31] | Versatile, no DSBs, no donor required | Complex pegRNA design |

Quantitative Assessment of Editing Outcomes

Rigorous quantification of editing outcomes is essential for evaluating the success of CRISPR experiments in primary cells. The table below summarizes expected efficiency ranges across different editing modalities and primary cell types, based on recent methodological advances.

Table 2: Efficiency Ranges Across Primary Cell Types and Editing Modalities

| Cell Type | Knock-out Efficiency | Knock-in Efficiency | Base Editing Efficiency | Prime Editing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary T Cells | 70-90% with RNP electroporation [1] | ~20% with RNP + ssODN [1] | Not specified | Not specified |

| hPSCs | 82-93% with optimized iCas9 [28] | Up to 37.5% with ssODN [28] | Not specified | Not specified |

| Germinal Center B Cells | Not specified | Challenging, requires HDR enhancement [27] | Not specified | Not specified |

| HEK293T (Reference) | >90% with multiple systems | ~2-fold increase with microfluidics vs electroporation [12] | Not specified | 34.8% with PE4 system [31] |

Experimental Protocols for Primary Cell Editing

Protocol 1: Knock-out in Hard-to-Transfect Primary Cells Using Lentiviral Delivery

This protocol adapts CRISPR knock-out methodology for hard-to-transfect primary immune cells, such as THP-1 monocytes, using lentiviral delivery to achieve stable gene disruption [32].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- sgRNA Design and Cloning: Design specific sgRNAs targeting early exons of the gene of interest. Clone annealed oligos into a lentiviral CRISPR vector (e.g., lentiCRISPRv2) using standard molecular biology techniques.

- Lentiviral Production: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the packaged CRISPR vector and viral packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G) using polyethylenimine (PEI) or commercial transfection reagents.

- Viral Harvest and Concentration: Collect viral supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection. Concentrate using ultracentrifugation or commercial concentration kits.

- Primary Cell Transduction: Transduce target primary cells with concentrated lentivirus in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/mL). Centrifuge plates to enhance infection efficiency if needed.

- Selection and Validation: Select transduced cells with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., puromycin 2 μg/mL) for 7-10 days. Validate knock-out efficiency via tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) analysis, Western blotting, or functional assays.

Critical Considerations: Monitor cell viability closely during selection. Include non-targeting sgRNA controls to account for potential off-target effects. For difficult-to-edit primary cells, consider optimizing multiplicity of infection (MOI) through dose-response experiments.

Protocol 2: Knock-in in Primary B Cells Using RNP Electroporation

This protocol describes HDR-mediated knock-in in primary human B cells and lymphoma cell lines, utilizing ribonucleoprotein (RNP) electroporation to enhance editing efficiency while minimizing cytotoxicity [27].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- sgRNA and HDR Template Design: Design sgRNAs with minimal off-target potential. For point mutations, design single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with 30-60 nt homology arms. For larger insertions, use double-stranded DNA templates with 200-300 nt homology arms.

- RNP Complex Assembly: Complex chemically modified sgRNAs with high-fidelity Cas9 protein to form RNP complexes. Incubate for 10-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Primary Cell Preparation: Isolate primary B cells from peripheral blood or tissue samples. Activate cells if necessary using CD40L and IL-4 for 24 hours to enhance HDR efficiency.

- Electroporation: Combine RNP complexes with HDR template and cells in electroporation cuvettes. Electroporate using optimized parameters (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector, program CA-137).

- Post-Electroporation Recovery: Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed culture medium with recovery supplements. Allow 48-72 hours for expression of inserted sequences before analysis.

- Validation: Assess knock-in efficiency using flow cytometry for reporter genes, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

Critical Considerations: HDR efficiency in B cells is limited by their quiescent state. Strategies to enhance HDR include synchronizing cells in S/G2 phase and using small molecule inhibitors of NHEJ such as Scr7 [27].

Protocol 3: Base Editing in Primary Cells Using RNP Delivery

This protocol outlines the application of cytosine or adenine base editors in primary cells using RNP delivery to minimize off-target effects and maximize editing efficiency [29] [30].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Base Editor Selection: Choose appropriate base editor (CBE or ABE) based on the desired nucleotide conversion. Consider newer generations with reduced off-target profiles.

- sgRNA Design for Base Editing: Design sgRNAs that position the target base within the editor's activity window (typically nucleotides 4-8 in the protospacer). Verify PAM compatibility.

- RNP Complex Formation: Complex base editor protein with chemically modified sgRNAs. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Cell Preparation and Delivery: Prepare primary cells as single-cell suspensions. Deliver RNP complexes via electroporation (e.g., Neon Transfection System) or advanced microfluidics [12].

- Analysis of Editing Outcomes: Harvest genomic DNA 72-96 hours post-editing. Analyze editing efficiency using Sanger sequencing with decomposition tools (ICE or BE-Analyzer) or deep sequencing.

Critical Considerations: Screen multiple sgRNAs to identify the most efficient editor. Check for potential bystander edits within the activity window. For therapeutic applications, perform comprehensive off-target assessment using whole-genome sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Delivery Platforms

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Primary Cell Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Considerations for Primary Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Format | Cas9-sgRNA RNP complexes [1] | Direct delivery of editing machinery; short half-life reduces off-targets | Less toxic than plasmid/mRNA; high efficiency in T cells |

| Base Editors | AccuBase CBE [29], ABE7.10 [29] | Precision point mutation correction without DSBs | Minimizes p53 response; editing window constraints |

| Delivery Systems | 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza) [1], Microfluidic DCP [12] | Physical delivery methods bypassing intracellular barriers | DCP shows 3.8x higher knock-in efficiency vs electroporation [12] |

| HDR Enhancers | Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein [31], Small molecule inhibitors (e.g., Scr7) | Increase HDR efficiency for knock-ins | Can improve efficiency 2-fold in hematopoietic stem cells [31] |

| sgRNA Modifications | 2'-O-methyl-3'-phosphorothioate [1] [28] | Enhanced nuclease resistance and stability | Critical for primary immune cells with high nuclease activity |

| Analytical Tools | ICE Analysis [28], FlowLogic, BE-Analyzer | Quantification of editing efficiency and outcomes | ICE validated against clone sequencing for accuracy [28] |

The expanding CRISPR toolkit offers multiple pathways for genetic manipulation in primary cells, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Knock-outs remain the most efficient approach for gene disruption, while knock-ins enable precise sequence insertion but with lower efficiency. Base editing and prime editing represent transformative technologies for precision genome engineering without DSBs, though their application in primary cells continues to be optimized.

Selection of the appropriate editing modality must be guided by experimental objectives, primary cell type, and technical constraints. As delivery technologies such as microfluidic mechanoporation continue to advance [12], and as precision editors evolve with reduced off-target profiles [31], the accessibility and efficiency of primary cell engineering will continue to improve, accelerating both basic research and therapeutic development.

State-of-the-Art Workflows: From RNP Delivery to High-Throughput Screening

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized biomedical research and therapeutic development, yet achieving efficient genome editing in primary cells remains a significant challenge. Unlike immortalized cell lines, primary cells—those isolated directly from human or animal tissues—are notoriously difficult to transfect due to their sensitivity, limited proliferative capacity, and innate immune mechanisms that degrade foreign genetic material [1]. The choice of how CRISPR components are delivered into these cells is therefore critical for success. Among the available formats—plasmid DNA, mRNA, or pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes—the RNP format has emerged as the unequivocal gold standard for primary cell engineering, offering superior editing efficiency, reduced cellular toxicity, and minimal off-target effects [33] [34].

The RNP complex consists of a purified Cas9 protein pre-complexed with an in vitro-transcribed or synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA). This complex is delivered directly into cells, where it can immediately localize to the nucleus and perform its editing function without the need for transcription or translation [35]. This direct delivery mechanism is particularly advantageous for primary cells, which have limited windows of viability ex vivo and often reside in quiescent states that hinder the processing of DNA-based editing constructs [27]. As the field advances toward clinical applications, including CAR-T cell therapies and regenerative medicine, the RNP platform provides the precision, safety, and efficiency required for the next generation of genetic medicines [36] [34].

The Scientific Rationale for the RNP Advantage

Enhanced Editing Efficiency and Reduced Cellular Toxicity

The pre-assembled nature of RNP complexes enables rapid genome editing, as the time-consuming intracellular steps of transcription and translation are bypassed. In direct comparisons, RNP delivery consistently outperforms plasmid DNA in primary cells. A study on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) demonstrated that RNP delivery achieved indel frequencies of up to 20.2%, significantly higher than the 9.0% achieved with plasmid DNA [34]. Similar results were observed in primary human T cells, where RNP delivery enabled editing efficiencies upwards of 80-90% [36]. This high efficiency is crucial for applications like generating B2M-knockout MSCs for improved survival in allogeneic settings, where editing efficiencies of 85.1% have been reported using RNPs [34].

Furthermore, RNP delivery is markedly less cytotoxic than plasmid-based approaches. Plasmids can trigger innate immune responses and cause significant stress to primary cells. In contrast, RNPs exhibit minimal toxicity, with cell viability frequently remaining above 90% post-transfection, even at high concentrations [34]. This high viability is essential when working with precious primary cell samples from patients, where every cell counts.

Minimized Off-Target Effects and Improved Specificity