Advanced pegRNA Design Strategies: Maximizing Prime Editing Efficiency for Therapeutic Applications

Prime editing represents a transformative advance in precision genome editing, yet its efficacy is critically dependent on the design of the prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA).

Advanced pegRNA Design Strategies: Maximizing Prime Editing Efficiency for Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

Prime editing represents a transformative advance in precision genome editing, yet its efficacy is critically dependent on the design of the prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing pegRNA design. We explore the foundational architecture of pegRNAs and the prime editing mechanism, detail cutting-edge methodological advances including engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) and computational design tools, address key troubleshooting challenges such as low efficiency and byproduct formation, and validate strategies through comparative analysis of next-generation systems. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to harness the full potential of prime editing for genetic research and therapeutic development.

Deconstructing the pegRNA: Core Components and the Prime Editing Mechanism

FAQ: Troubleshooting pegRNA Design and Efficiency

What are the core components of a pegRNA and their functions?

A pegRNA consists of four primary sequence parts that guide the prime editor and encode the desired genetic change.

- Spacer: A typically 20-nucleotide sequence that directs the Cas9 nickase to the specific target DNA site via complementary base pairing.

- Scaffold: The region that forms a secondary structure necessary for binding the Cas9 nickase protein, enabling its function.

- Reverse Transcription Template (RTT): Encodes the desired edit and provides a homology sequence for the DNA repair process. The length can vary but often starts at 10-16 nucleotides for initial testing.

- Primer Binding Site (PBS): A 10-15 nucleotide sequence that serves as an anchor point, annealing to the nicked DNA strand to initiate DNA synthesis by the reverse transcriptase [1].

How can I optimize the PBS and RTT sequences for better editing efficiency?

Optimizing the length and composition of the PBS and RTT is critical for successful prime editing. The following table summarizes key design parameters based on published recommendations [2].

| Component | Key Optimization Parameter | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| PBS (Primer Binding Site) | Length | Test different lengths, starting with ~13 nucleotides [2]. |

| GC Content | Aim for 40–60% GC content for most successful outcomes [2]. | |

| RTT (Reverse Transcription Template) | Length | Test different lengths, starting with ~10-16 nucleotides [2]. |

| 5' Nucleotide | The first base of the 3' extension should not be a C to avoid disruptive base pairing with the gRNA scaffold [2]. |

My prime editing efficiency is low. What are some advanced strategies to improve it?

Low efficiency can stem from several issues, including pegRNA degradation or misfolding. The table below outlines advanced engineering strategies.

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| epegRNAs [3] | Adds a stabilizing RNA motif (e.g., evopreQ1 or mpknot) to the 3' end of the pegRNA to protect it from exonucleolytic degradation. | Improved prime editing efficiency 3 to 4-fold on average in multiple human cell lines (HeLa, U2OS, K562) without increasing off-target effects [3]. |

| pegRNA Refolding [4] | A simple procedure of heat denaturation followed by slow cooling to re-fold the pegRNA into its correct, functional conformation. | Improved ribonucleoprotein-mediated PE efficiencies in zebrafish embryos by up to nearly 25-fold by resolving internal misfolding [4]. |

| Same-Sense Mutations (spegRNA) [5] | Introduces additional, silent point mutations in the RTT to create a "bubble" of multiple mismatches that is less efficiently recognized and reversed by the cellular mismatch repair (MMR) system. | Increased base-editing efficiency by up to 4,976-fold (on-average 353-fold) by evading MMR [5]. Introducing two mutations at positions 2/5 or 3/6 (counting from the 3' end of the RTT) was particularly effective [5]. |

| Point Mutations in RTT [4] | Introducing specific point mutations (e.g., at RTT+1 or RTT+2) to disrupt internal complementary sequences within the pegRNA that cause misfolding. | Mutations at the RTT+2 position increased pure PE frequency by up to 6.7-fold (mean 2.4-fold) in zebrafish embryos [4]. |

How can I reduce undesired byproducts like scaffold sequence incorporation?

A common undesired byproduct is the incorporation of parts of the pegRNA scaffold into the genome. Structural studies reveal that the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (RT) can sometimes continue reverse transcription beyond the end of the RTT and into the scaffold region of the pegRNA [6]. To mitigate this:

- Rational Engineering: Based on structural insights, you can rationally engineer pegRNA variants or fuse the M-MLV RT within SpCas9 at positions that limit over-extension [6].

- Avoid Homology: When using MMR-inhibiting systems like PE4/PE5, ensure the pegRNA scaffold sequence is not homologous to the target genomic site to prevent incorrect incorporation [2].

What is the role of a nicking sgRNA (ngRNA), and how should I design it?

Systems like PE3 and PE5 use a second, standard sgRNA to nick the non-edited DNA strand. This encourages the cell to use the edited strand as a template during repair, thereby boosting editing efficiency [2].

- Design: Test multiple nick sites, starting with sites approximately 50 bp upstream or downstream from the original prime editing nick site [2].

- High-Fidelity Design (PE3b/PE5b): For lower indel rates, design the ngRNA so that it can only bind and nick after the edit has been installed on the opposite strand. This approach, known as PE3b/PE5b, reduces concurrent nicks and is recommended over PE3/PE5 when possible [2].

Experimental Protocols

This protocol helps resolve internal misfolding in pegRNAs that can inhibit Cas9 binding.

- Resuspension: Dilute the synthesized pegRNA in nuclease-free buffer or water.

- Denaturation: Heat the pegRNA to 65-75°C for 2-5 minutes.

- Refolding: Slowly cool the pegRNA to room temperature over 20-30 minutes. This can be done by turning off the heating block and letting it cool naturally or by using a thermal cycler with a controlled ramp rate.

- Storage: Use immediately or store at -20°C for later use. Always keep on ice when in use.

This strategy enhances editing efficiency by confounding the cellular mismatch repair system.

- Identify Codons: Within the reverse transcriptase template (RTT) of your pegRNA, identify codons where you can introduce silent mutations that do not change the encoded amino acid.

- Select Positions: Focus on introducing one or two same-sense mutations. The most effective positions are often:

- A single mutation at position 1, 5, or 6 (counting the 3'-base of the RTT as position 1).

- Two mutations simultaneously at positions 2/5 or 3/6.

- Design and Test: Design a small panel of 1-5 spegRNAs incorporating these mutations and test them empirically against your target.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

pegRNA Optimization Decision Workflow

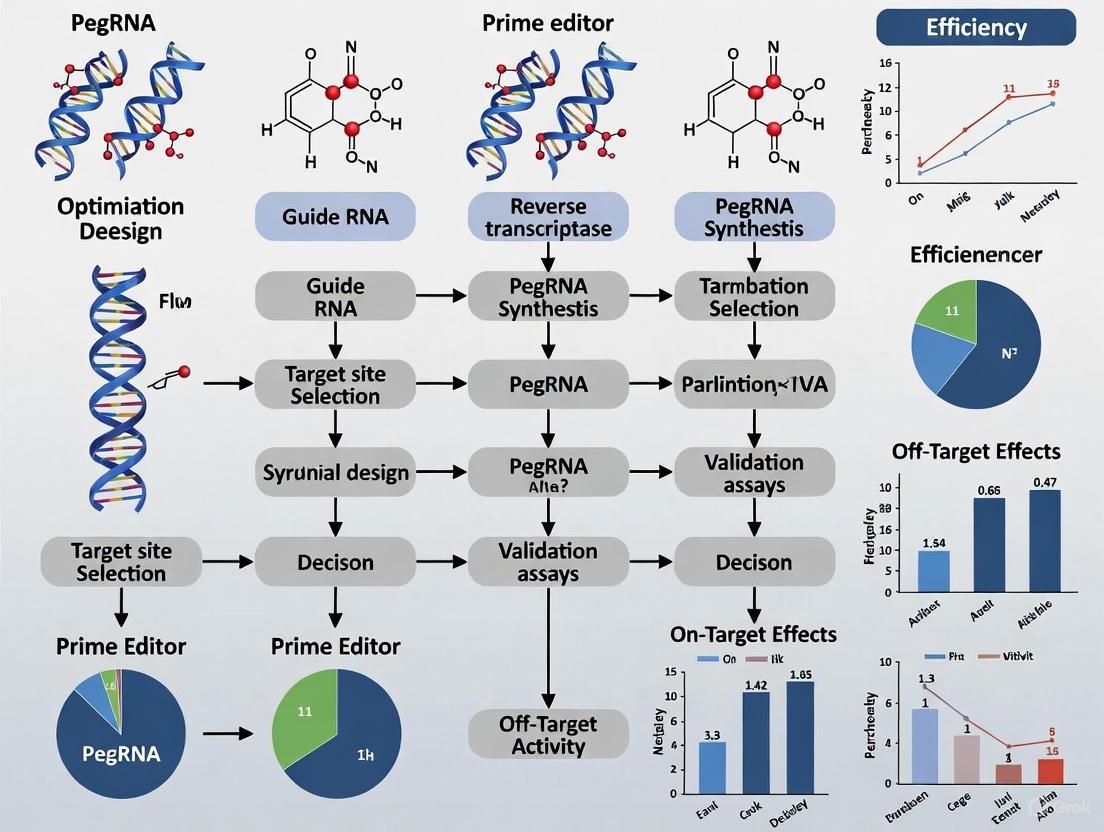

This diagram illustrates a logical workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing pegRNA design to improve prime editing efficiency.

Mechanism of Undesired Scaffold Incorporation

Structural studies have revealed how reverse transcription can extend beyond the intended RTT, leading to the incorporation of pegRNA scaffold sequences into the genome, a major undesired byproduct [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Prime Editing | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| EnginepegRNAs (epegRNAs) [3] | pegRNAs with 3' terminal RNA motifs (evopreQ1, mpknot) that protect against exonuclease degradation, enhancing stability and efficiency. | Use computational tools like pegLIT to design linkers that minimize unwanted intra-RNA base pairing [2]. |

| PE Systems (PE2, PE3, PE5) [2] [1] | Progressive generations of prime editors. PE2 is the basic system; PE3 adds a nicking sgRNA; PE5 combines a nicking sgRNA with MMR inhibition. | PE3b/PE5b systems, where the nicking sgRNA targets the edited sequence, are recommended to reduce indel byproducts [2]. |

| MMR Inhibitors (e.g., MLH1dn) [2] | Suppresses the mismatch repair pathway, which can reverse prime edits, thereby improving the persistence of installed edits. | Ensure pegRNA scaffold has no homology to the genomic target to prevent unintended edits when MMR is inhibited [2]. |

| La Protein / PE7 [2] | An RNA-binding protein (fused in PE7 or endogenous) that binds 3' polyU tracts on pegRNAs, protecting them from degradation. | Adding 3' polyU tracts can improve PE efficiency for standard pegRNAs, but this is not used with epegRNAs [2]. |

How Prime Editing Works: A Visual Guide

The prime editing mechanism is a precise, multi-step process that enables "search-and-replace" genome editing without double-strand breaks. The following diagram illustrates the complete pathway from initial target binding to final flap resolution.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Prime Editing Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Optimization Strategies | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | - pegRNA degradation [3]- Suboptimal PBS/RTT length [2]- Cellular MMR reversal [7] [8] | - Use epegRNAs with 3' RNA motifs (evopreQ1, mpknot) [3]- Test PBS lengths of ~13 nt and RTT lengths of 10-16 nt [2]- Employ PE4/PE5 systems with MLH1dn to inhibit MMR [9] [8] | 3-4× efficiency improvement with epegRNAs [3]; 7.7× improvement with PE4 vs PE2 [8] |

| High indel formation | - Concurrent nicking of both strands [1] [8]- pegRNA scaffold homology to target site [2] | - Use PE3b system with nicking sgRNA that targets only edited strand [1] [8]- Ensure no homology between pegRNA scaffold and genomic target [2] | 13-fold reduction in indels with PE3b vs PE3 [8] |

| Inefficient flap resolution | - MMR bias against edited strand [7]- Short heteroduplex region | - Incorporate silent mutations to create 3+ base "bubbles" that evade MMR [2]- Edit the PAM sequence to prevent re-nicking [2] | Improved heteroduplex resolution in favor of edited strand |

| Off-target effects | - pegRNA spacer homology to non-target sites [10] | - Use computationally optimized spacers with minimal off-target potential- Employ systems requiring three binding events (spacer, PBS, 3' flap) [9] | Lower off-target effects compared to CRISPR-Cas9 [10] [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Optimizations

Protocol: Engineering pegRNAs (epegRNAs) for Enhanced Stability

Background: Traditional pegRNAs are susceptible to 3' degradation, producing truncated RNAs that compete for target sites but cannot mediate editing [3]. Engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) incorporate structured RNA motifs that protect against exonuclease degradation.

Materials:

- RNA synthesis capability for extended pegRNAs (110-266 nt) [11]

- evopreQ1 (42 nt) or mpknot RNA motifs [3]

- 8-nt non-interfering linker sequences (design with pegLIT tool) [3] [2]

Method:

- Design standard pegRNA with spacer, scaffold, RTT, and PBS sequences

- Append an 8-nt linker to the 3' end of the PBS using ViennaRNA for design [3]

- Add evopreQ1 or mpknot RNA motif to the 3' terminus [3]

- Synthesize and purify using HPLC grade for optimal results [11]

- Validate editing efficiency in HEK293T cells comparing to canonical pegRNA

Expected Results: epegRNAs show 3-4× higher editing efficiency in HeLa, U2OS, and K562 cells without increasing off-target effects [3].

Protocol: PE3b System for Reduced Indel Formation

Background: The PE3 system increases editing efficiency by nicking the non-edited strand but can raise indel rates due to concurrent nicking. PE3b addresses this by designing the nicking sgRNA to target only after the edit is installed [1] [8].

Materials:

- PE2 enzyme (Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion) [8]

- pegRNA encoding desired edit

- Nicking sgRNA designed to match edited sequence

Method:

- Design pegRNA with standard parameters (13 nt PBS, 10-16 nt RTT) [2]

- Design nicking sgRNA with spacer complementary to the edited sequence, not the wild-type allele

- Transfert cells with PE2 + pegRNA + nicking sgRNA plasmids

- Analyze editing efficiency and indel rates via sequencing

- Compare to PE3 system with standard nicking sgRNA

Expected Results: PE3b achieves similar editing efficiencies as PE3 but with 13-fold reduction in indel formation [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Prime Editing Research

| Reagent Type | Key Examples | Specifications | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Proteins | PE2, PEmax, PE6 variants [8] | Cas9(H840A)-RT fusions with varying mutations | Core editing machinery; PEmax offers codon optimization for human cells [8] |

| pegRNA Synthesis | HPLC-purified pegRNAs [11] | 110-266 nt length, ≥85% purity, modifications available | Encoding target site and desired edit; critical for experimental success |

| Stability-Enhanced RNAs | epegRNAs [3] | pegRNAs with 3' evopreQ1 or mpknot motifs | Improved editing efficiency (3-4×) by preventing degradation |

| MMR Inhibition | MLH1dn plasmid [9] [8] | Dominant-negative MLH1 variant | Increases editing efficiency in PE4/PE5 systems by reducing edit reversal |

| Delivery Tools | PE2/PE3 mRNA [11] | Modified mRNA (Cap1, m1Ψ) for reduced immunogenicity | Enables transient editor expression without viral vectors |

| Validation Primers | Target-specific primers [11] | Amplify edited genomic regions | Essential for quantifying editing efficiency and specificity |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of prime editing over base editing and traditional CRISPR-Cas9 systems?

Prime editing offers several distinct advantages: (1) It enables all 12 possible base-to-base conversions without DNA double-strand breaks, unlike CRISPR-Cas9 which relies on error-prone repair of DSBs [7] [8]; (2) It has greater targeting flexibility than base editors, which are constrained by the need for a precisely positioned PAM sequence within their editing window [8]; (3) It produces fewer indel byproducts than Cas9-initiated homology-directed repair [10] [8]; (4) It can install small insertions and deletions in addition to point mutations [1].

Q2: Why does prime editing efficiency vary between cell types, and how can this be addressed?

Editing efficiency depends on cellular factors including DNA repair pathway activity, pegRNA stability, and reverse transcriptase processivity [7] [3]. Different cell types express varying levels of mismatch repair proteins that can reverse prime edits [8]. To address this: (1) Use the PE4/PE5 systems with MLH1dn to transiently inhibit MMR in refractory cell types [9] [8]; (2) Employ epegRNAs to protect against exonuclease degradation [3]; (3) Optimize PBS and RTT lengths empirically for each cell type [2].

Q3: What are the most critical parameters for designing effective pegRNAs?

Optimal pegRNA design requires attention to several parameters: (1) Primer binding site length of ~13 nucleotides with 40-60% GC content [2]; (2) Reverse transcriptase template length of 10-16 nucleotides for most edits [2]; (3) Avoidance of C as the first base of the 3' extension to prevent disruptive base pairing [2]; (4) Incorporation of PAM edits when possible to prevent re-nicking of edited strands [2]; (5) Use of 3' RNA structural motifs or polyU tracts (for PE7) to enhance stability [3] [2] [8].

Q4: What recent advancements address the delivery challenges of prime editing components?

Recent innovations focus on: (1) Smaller prime editors (PE6a, PE6b) that can be packaged into AAV vectors [8]; (2) Engineered pegRNAs with improved stability (epegRNAs, petRNAs) [3] [12]; (3) PE7 system which fuses the La protein to stabilize pegRNAs [8]; (4) proPE system which separates nicking and templating functions for more efficient editing [12]; (5) Optimized mRNA and LNP formulations for transient delivery [7] [11].

Prime editing represents a transformative "search-and-replace" genome editing technology that directly writes new genetic information into a specified DNA site without requiring double-strand breaks (DSBs) or donor DNA templates [13] [14]. This technology has evolved significantly from its initial conception to more advanced systems, with continuous improvements focused on enhancing editing efficiency, specificity, and delivery capabilities. The optimization of prime editor proteins and pegRNA design has been central to this evolution, enabling broader application across research and therapeutic contexts [15] [16].

At its core, prime editing employs a fusion protein consisting of a Cas9 nickase (nCas9) reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme complex, programmed with a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [17] [18]. The pegRNA both specifies the target genomic location and encodes the desired edit, making its design a critical determinant of editing success. This technical support center addresses the key challenges researchers face when implementing prime editing systems, with particular emphasis on pegRNA design optimization within the broader context of prime editor evolution from PE1 to advanced PE6 systems.

Prime Editor Evolution: From PE1 to PE6

Developmental Timeline and Key Improvements

The progression of prime editing systems has involved strategic engineering of both the editor protein and auxiliary components to enhance performance across diverse editing contexts.

Table 1: Evolution of Prime Editing Systems from PE1 to PE6

| System | Key Components | Editing Efficiency | Major Innovations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | nCas9(H840A) + M-MLV RT + pegRNA | ~10-20% in HEK293T cells [18] | Founding proof-of-concept system [18] | Initial demonstration of prime editing principle |

| PE2 | nCas9(H840A) + engineered M-MLV RT (5 mutations) + pegRNA [19] [18] | ~20-40% in HEK293T cells [18] | 5 RT mutations (D200N/L603W/T330P/T306K/W313F) enhancing activity, binding, and thermostability [19] | General-purpose editing with improved efficiency over PE1 |

| PE3 | PE2 system + additional nicking sgRNA [19] [18] | ~30-50% in HEK293T cells [18] | Dual-nicking strategy to encourage use of edited strand as repair template [18] | Applications requiring higher editing efficiency |

| PE4 | PE2 system + MLH1dn (MMR inhibition) [19] | ~50-70% in HEK293T cells [18] | Mismatch repair inhibition to reduce correction of edited strands [19] | Editing in MMR-proficient contexts |

| PE5 | PE3 system + MLH1dn (MMR inhibition) [19] | ~60-80% in HEK293T cells [18] | Combines dual nicking with MMR inhibition [19] | High-efficiency editing with reduced off-target effects |

| PEmax | Codon-optimized nCas9 + engineered RT + nuclear localization signals [19] | Improved over PE2 | Architecture optimization, linker engineering, and improved expression [19] | Versatile high-performance editing |

| PE6 | Evolved RT variants (PE6a-d) and Cas9 variants (PE6e-g) + epegRNAs [15] [19] | ~70-90% in HEK293T cells [18]; 22-fold improvement for compact RTs [15] | Phage-assisted evolution of compact RTs; engineered Cas9 domains [15] | Therapeutic applications with enhanced efficiency and delivery |

Key Experimental Workflows in Prime Editor Development

The development of advanced prime editors has employed several sophisticated protein engineering and evolution methodologies:

Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE) for PE6 Development:

- Objective: Evolve compact reverse transcriptases with improved prime editing efficiency [15]

- Methodology:

- Implement continuous evolution system linking prime editing activity to phage propagation

- Apply selective pressure for improved editing efficiency over multiple generations

- Screen evolved RT variants across multiple edit types and cell lines

- Outcome: Identification of PE6a-d variants with up to 22-fold improved editing efficiency and reduced size (516-810 bp smaller than PEmax) [15]

Rational Engineering of Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes:

- Objective: Improve RT performance through structure-guided mutagenesis [15]

- Methodology:

- Install analogous mutations to PE2's five mutations (D200N, T306K, W313F, T330P, L603W) in various RTs

- Use AlphaFold2-predicted structures to guide mutations for RTs without crystal structures

- Test individual and combined mutations across multiple edits in HEK293T cells

- Outcome: 5.3-fold to 6.8-fold improvement in editing efficiency for engineered RTs compared to wild-type versions [15]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Prime Editing Challenges

pegRNA Design and Optimization Issues

Problem: Low editing efficiency across multiple targets

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal primer binding site (PBS) length or reverse transcriptase template (RTT) design [2]

- Solution:

- Systematically test PBS lengths starting from 13 nucleotides [2]

- Optimize RTT length to approximately 10-16 nucleotides for standard edits [2]

- Maintain PBS GC content between 40-60% where possible [2]

- Avoid 'C' as the first base of the 3′ pegRNA extension to prevent non-canonical base pairing with G81 of the gRNA scaffold [2]

- Advanced Solution: Implement engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) with evopreQ1 or mpknot motifs at the 3′ end to protect against degradation [16]

Problem: High indel rates alongside desired edits

- Potential Cause: Repeated nicking of the newly synthesized strand due to intact PAM sequence [2]

- Solution: Incorporate PAM-disrupting mutations as part of the edit to prevent re-binding of the editor [2]

- Alternative Solution: Use PE3b/PE5b systems with nicking sgRNAs designed to bind only after the edit is installed [2]

Problem: Inconsistent performance across cell types

- Potential Cause: Variable expression levels of prime editors and pegRNAs [20]

- Solution: Implement stable genomic integration using piggyBac transposon system for consistent editor expression [20]

- Validation Approach: Use single-cell cloning to establish lines with verified editor expression and function [20]

Editor Selection and Delivery Challenges

Problem: Limited delivery capacity for in vivo applications

- Potential Cause: Large size of prime editor components exceeding viral packaging limits [15]

- Solution: Utilize compact PE6 variants (PE6a-b) with reduced-size RTs (516-810 bp smaller than PEmax) [15]

- Alternative Solution: Employ dual-AAV delivery systems with split editor components [15] [16]

Problem: Poor performance with long, complex edits

- Potential Cause: Limitations in RT processivity or flap resolution [15]

- Solution: Select appropriate RT variants specialized for different edit types (PE6 editors show specialization for specific edit classes) [15]

- Advanced Solution: For insertions >30 bp, consider twinPE or PASSIGE systems for large DNA integrations [13] [19]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key considerations when choosing between PE2, PE3, PE4, and PE5 systems?

- A: System selection depends on your specific application requirements. PE2 provides a solid foundation with reasonable efficiency. PE3 enhances efficiency through an additional nicking sgRNA but may increase indel rates. PE4 and PE5 incorporate MLH1dn to inhibit mismatch repair, significantly improving efficiency particularly in mismatch repair-proficient contexts but requiring careful design to prevent undesired outcomes [19] [18]. For therapeutically relevant editing in patient-derived fibroblasts and primary human T-cells, PE6 variants have demonstrated enhanced performance [15].

Q2: How does pegRNA design differ for various prime editor generations?

- A: While the core principles of pegRNA design remain consistent across systems, advanced editors like PE6 benefit from optimized pegRNA architectures. For all systems, begin with standard PBS lengths of ~13 nt and RTT of ~10-16 nt. For PE6 systems, incorporate epegRNA designs with structured RNA motifs for enhanced stability. The first base of the 3′ extension should not be 'C' in any system to prevent non-canonical gRNA binding [2].

Q3: What delivery methods show highest efficiency for prime editors?

- A: Delivery optimization significantly impacts editing outcomes. Recent research demonstrates that combining piggyBac transposon system for stable editor integration with lentiviral delivery of epegRNAs achieves up to 80% editing efficiency across multiple cell lines [20]. For in vivo applications, dual-AAV delivery of PE6 systems achieved 40% loxP insertion in mouse cortex, a 24-fold improvement over previous systems [15].

Q4: How can I address the challenge of installing long insertions (>100 bp)?

- A: For large insertions, consider these approaches:

- TwinPE: Uses two pegRNAs to edit both DNA strands, enabling larger insertions and deletions [13]

- PASSIGE (Prime Assisted Site-Specific Integrase Gene Editing): Combines prime editing with recombinases for gene-sized insertions [13] [19]

- PE6 with dual-AAV: Enables longer insertions (38-42 bp) with 12-183-fold improvements in efficiency compared to earlier systems [15]

Table 2: Prime Editing Efficiency Optimization Strategies

| Challenge | Standard Approach | Enhanced Approach | Expected Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Efficiency | PE2 with standard pegRNA | PE6 with epegRNA + MMR inhibition | Up to 22-fold with PE6 editors [15] |

| Delivery Limitations | Single-vector delivery | Dual-AAV with compact PE6 variants | 24-fold improvement in vivo [15] |

| Large Insertions | Standard PE | TwinPE or PASSIGE | Insertions >5,000 bp possible [13] [19] |

| Cell-Type Specific Challenges | Transient transfection | Stable integration via piggyBac | Up to 80% efficiency in multiple cell lines [20] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Prime Editing Optimization

| Reagent | Function | Examples/Specifications | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Plasmids | Core editing machinery | PEmax (Addgene #174828), PE6 variants | Base editor proteins for different systems |

| pegRNA Expression Vectors | Edit specification | epegRNA backbones with evopreQ1/mpknot | Stabilized pegRNAs for improved efficiency |

| MMR Inhibition Components | Enhance editing efficiency | MLH1dn (dominant-negative MLH1) | PE4/PE5 systems for MMR-proficient contexts |

| Delivery Systems | Editor and guide delivery | piggyBac transposon, lentiviral vectors, AAV | Cell-type specific delivery optimization |

| Validation Tools | Edit confirmation | Next-generation sequencing, T7E1 assay | Efficiency and specificity assessment |

Advanced Workflow: Systematic Prime Editing Optimization

Comprehensive Optimization Protocol:

- Initial pegRNA Design

- Design 3-4 pegRNAs per target with varying PBS lengths (10-15 nt) and RTT configurations

- Incorporate structured RNA motifs (evopreQ1 or mpknot) for epegRNA designs

- Include silent mutations to create 3-base or longer tracts when possible to evade MMR [2]

Editor Selection Matrix

- Test PE2, PEmax, and appropriate PE6 variants in parallel

- For challenging edits, include PE4/PE5 with MLH1dn for MMR inhibition

- For therapeutic applications requiring viral delivery, prioritize compact PE6 variants

Delivery Optimization

Validation and Iteration

- Quantify editing efficiency using next-generation sequencing (minimum 5000x coverage)

- Assess indel formation and off-target effects using targeted sequencing

- Iterate on pegRNA design based on initial results, focusing on optimal performers

This systematic approach combining pegRNA design optimization with appropriate editor selection and delivery methods has demonstrated substantial improvements in prime editing efficiency, achieving up to 80% editing in cell lines and 50% in human pluripotent stem cells [20].

Understanding Editing Windows and Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) Constraints

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary constraints of the prime editing (PE) window? The canonical prime editing window is constrained by its mechanism, which limits efficient editing to positions within approximately 30 base pairs (bp) downstream (3') of the nick site created by the Cas9 nickase on the non-target strand [8]. Editing efficiency typically decreases for edits located further from the nick site, particularly beyond the +12 to +15 position [21] [22]. This is partly due to the challenge of fully synthesizing long reverse transcriptase templates without degradation [12].

2. How does PAM availability limit targetable sites for prime editing? The PAM sequence is an absolute requirement for the Cas9 protein to bind DNA. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the canonical PAM is 5'-NGG-3'. This sequence must be present on the non-target DNA strand, positioning the nick site 3-4 bp upstream (5') of the PAM [8] [22]. The need for a specific PAM sequence at a precise location and orientation relative to the target edit can render some genomic sites inaccessible, creating "PAM deserts" [8].

3. What strategies can overcome PAM and editing window constraints? Recent advances have developed several strategies to overcome these limitations, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Strategies to Overcome PAM and Editing Window Constraints

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Advantage | Example System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Prime Editing (rPE) [21] | Uses Cas9-D10A nickase to nick the target strand, enabling editing in the 5' direction from the HNH nick site. | Expands the editing scope to the 5' direction; potentially higher fidelity due to reduced double-strand break formation. | rPE2, rPE3 |

| Prolonged Editing Window (proPE) [12] | Separates the nicking and templating functions onto two different sgRNAs (engRNA and tpgRNA). | Extends the effective editing window and enhances efficiency for edits distant from the nick site. | proPE |

| Engineered Cas9 Variants [23] | Incorporates mutations (e.g., K848A, H982A) to relax nick positioning and promote 5' strand degradation. | Reduces indel errors by up to 36-fold, improving the edit-to-indel ratio. | pPE (precise Prime Editor) |

| PAM-Relaxed Cas Domains [22] | Utilizes engineered Cas proteins like SpRY or other orthologs with altered PAM requirements. | Increases the number of targetable sites in the genome by relaxing the strict NGG PAM requirement. | PE-SpRY |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Editing Efficiency for Edits Distant from the PAM Site

Potential Cause: The edit is located at a suboptimal position within the prime editing window, where reverse transcription efficiency drops.

Solutions:

- Utilize the proPE system: Co-deliver an essential nicking guide RNA (engRNA) and a separate template-providing guide RNA (tpgRNA). The tpgRNA uses a truncated spacer (11-15 nt) that binds DNA without nicking, locally presenting the template near the edit site. This can increase editing efficiency for low-performing edits by an average of 6.2-fold [12].

- Employ a twin-pe strategy: If the edit is very large, consider using two pegRNAs that target opposite strands to create complementary flaps [22].

- Consider Reverse PE (rPE): If the PAM orientation allows, design an rpegRNA for the rPE system, which establishes an editing window on the opposite side of the nick [21].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Efficiency and Off-Target Effects

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low efficiency for edits >12bp from nick | Incomplete DNA flap synthesis/degradation [12] | Switch to the proPE system [12]. |

| High indel byproducts | Re-nicking of the edited strand or MutSα–MutLα mismatch repair activity [8] [23] | Use the PE3b system; or employ PEmax with MMR inhibition (PE4/PE5 systems) [8]; or use the high-fidelity pPE editor [23]. |

| Inefficient editing in a "PAM desert" | Lack of an NGG PAM sequence near the target site [8] | Use an rPE system to access a different editing window [21]; or employ a PAM-relaxed Cas variant [22]. |

| Low pegRNA stability | Degradation of the 3' extension (PBS/RTT) of the pegRNA [8] | Use epegRNAs with engineered RNA pseudoknots to protect the 3' end, or use the PE7 system which fuses the La protein to stabilize pegRNAs [8]. |

Issue: High Indel Byproducts

Potential Cause: The non-edited strand is being nicked by the Cas9 nickase before the heteroduplex is resolved, leading to double-strand breaks repaired by error-prone pathways [8] [23].

Solutions:

- Use the PE3b system: This system uses a nicking sgRNA (ngRNA) designed to bind only after the edit has been incorporated into the primary strand, reducing the chance of simultaneous nicking [8].

- Inhibit Mismatch Repair (MMR): Use the PE4 or PE5 system, which co-expresses a dominant-negative MLH1 mutant to transiently inhibit MMR, favoring the retention of the edited strand [8].

- Employ a high-fidelity editor: Use the recently engineered pPE (K848A-H982A), which relaxes nick positioning to promote degradation of the competing 5' strand, reducing indels by up to 36-fold compared to standard PE [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the proPE System to Extend the Editing Window

Purpose: To significantly improve prime editing efficiency for edits that are distal from the canonical nick site or otherwise inefficient [12].

Materials:

- Prime editor protein (e.g., PEmax)

- Essential nicking guide RNA (engRNA): A standard sgRNA targeting the desired genomic site.

- Template-providing guide RNA (tpgRNA): An sgRNA with a truncated spacer (11-15 nucleotides) targeting a site near the intended edit. Its 3' extension contains the PBS and RTT, but it does not induce a nick.

Method:

- Design: Design the engRNA to create the initial nick. Design the tpgRNA to bind a genomic site as close as possible to the intended edit. The truncated spacer ensures the PE complex binds DNA without cleaving it.

- Delivery: Co-transfect cells with plasmids encoding the prime editor, the engRNA, and the tpgRNA. The optimal ratio of engRNA to tpgRNA should be determined empirically.

- Optimization: Titrate the amount of engRNA plasmid. High levels of engRNA can lead to re-nicking and reduce efficiency. The amount of tpgRNA can be increased until efficiency saturates [12].

- Analysis: Assess editing efficiency 72-96 hours post-transfection using amplicon deep sequencing.

Protocol 2: Applying Reverse Prime Editing (rPE)

Purpose: To create an editing window on the 5' side of the HNH-mediated nick site, thereby accessing new genomic territory and potentially reducing unwanted byproducts [21].

Materials:

- Reverse Prime Editor protein (e.g., rPE2): A fusion of Cas9-D10A nickase and M-MLV reverse transcriptase.

- Reverse pegRNA (rpegRNA): Designed based on the target DNA strand. The PBS of the rpegRNA binds to the DNA sequence adjacent to the 5' terminus of the HNH-mediated nick site.

Method:

- Design: Identify a PAM sequence and design the rpegRNA spacer to be complementary to the target strand. The PBS and RTT in the rpegRNA's 3' extension are designed to encode the desired edit within the new 5' editing window.

- Delivery: Transfect cells with the rPE2 (or optimized rPE7max) editor and the rpegRNA.

- Enhancement (Optional): For higher efficiency, include a nicking sgRNA to create the rPE3 system, which nicks the non-edited strand to bias repair in favor of the edit [21].

- Analysis: Validate editing outcomes and specificity using next-generation sequencing.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced Prime Editing Applications

| Reagent / System | Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| PEmax [8] | An optimized prime editor architecture with codon-optimized RT, additional NLS, and Cas9 mutations. | General purpose prime editing with improved expression and activity in human cells. Serves as the base for many advanced systems. |

| pPE (precise Prime Editor) [23] | A prime editor (K848A-H982A) that relaxes nick positioning to promote 5' strand degradation. | Achieving extremely high-fidelity edits with dramatically reduced indel errors (up to 36-fold lower). |

| rPE2 / rPE7max [21] | A prime editor using Cas9-D10A to create a reverse editing window on the target strand. | Accessing edits 5' of the PAM site; potentially higher fidelity editing due to reduced DSB formation. |

| proPE System [12] | A dual-guide system separating nicking (engRNA) and templating (tpgRNA) functions. | Enhancing efficiency for edits distant from the nick site and expanding the effective editing window. |

| epegRNA [8] | An engineered pegRNA with 3' RNA pseudoknots to protect against degradation. | Stabilizing pegRNA structure to increase the availability of intact template for reverse transcription. |

| PE4/PE5 System [8] | A prime editing system co-expressing a dominant-negative MLH1dn to transiently inhibit mismatch repair. | Improving editing efficiency by biasing cellular repair to favor the edited strand, especially in PE3 mode. |

Strategic pegRNA Engineering and Computational Design Tools

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary cause of low prime editing efficiency, and how do epegRNAs address this? The primary cause is the degradation of the pegRNA's 3' extension, which contains the primer binding site (PBS) and reverse transcription template (RTT). Unlike the guide portion that is protected by the Cas9 protein, this 3' extension is exposed and susceptible to cellular exonucleases. Truncated pegRNAs can still bind the target site but are incompetent for editing, thereby poisoning the process by occupying the editor without performing the desired function [3]. epegRNAs address this by incorporating stable RNA pseudoknots at their 3' terminus. These structured motifs act as protective barriers, shielding the pegRNA from degradation and significantly enhancing its intracellular stability and lifetime, which in turn improves editing efficiency [3] [24].

2. Which RNA motifs are most effective for stabilizing pegRNAs? Research has identified several effective RNA motifs. The most commonly used are the evopreQ1 pseudoknot (a 42-nt prequeosine-1 riboswitch aptamer) and the mpknot pseudoknot (from the Moloney murine leukemia virus frameshifting element) [3]. An alternative approach uses xrRNA motifs derived from flaviviruses like Zika virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus, which are renowned for their mechanical rigidity and resistance to exonucleases [24]. The table below summarizes the performance of these different motifs.

Table 1: Comparison of Protective RNA Motifs for epegRNAs

| Motif Name | Origin | Key Features | Reported Average Efficiency Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| evopreQ1 | Bacterial riboswitch [3] | Small size (42 nt), defined tertiary structure [3] | 3 to 4-fold in multiple cell lines [3] |

| mpknot | Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) [3] | Endogenous template for MMLV RT, tertiary structure [3] | 3 to 4-fold in multiple cell lines [3] |

| xrRNA (e.g., Zika) | Flaviviruses (e.g., Zika virus) [24] | Knot-like structure, mechanically rigid, confers exonuclease resistance [24] | Up to 3.1-fold for base conversions [24] |

3. Is a linker sequence necessary when appending these motifs to a pegRNA? Yes, using a linker is generally recommended. An 8-nucleotide (nt) linker between the PBS and the protective motif can prevent steric clashes and unwanted base-pairing interactions that might interfere with the reverse transcription process or the folding of the pseudoknot itself [3]. While one study found that epegRNAs with the smaller evopreQ1 motif were less affected by linker omission, performance can be variable, and including a linker provides more consistent results [3]. Computational tools like pegLIT are available to help design optimal, non-interfering nucleotide linkers [3] [2].

4. Do epegRNAs increase the risk of off-target editing? Extensive studies have shown that the use of epegRNAs does not increase off-target editing activity. The protective motifs enhance the stability and functional capacity of pegRNAs without altering the inherent specificity of the prime editor complex. The edit-to-indel ratios and off-target profiles remain comparable to, or are sometimes improved over, those of canonical pegRNAs [3] [24].

5. Besides epegRNAs, what other strategies can improve pegRNA stability? Another prominent strategy involves leveraging the La protein, an endogenous RNA-binding protein that stabilizes RNAs with 3' poly(U) tracts. The PE7 system fuses a fragment of the La protein directly to the prime editor. This fusion recruits the cellular La protein to the pegRNA, further protecting it from degradation and offering an alternative or complementary stabilization method [8] [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistently Low Prime Editing Efficiency

Potential Cause: The pegRNA is being degraded, or its design is suboptimal.

Solution Checklist:

- Switch to epegRNAs: Replace standard pegRNAs with epegRNAs incorporating either the evopreQ1 or mpknot motif. This is one of the most impactful steps to overcome degradation [3].

- Use a Linker: Ensure your epegRNA design includes an 8-nt linker between the PBS and the protective RNA motif. Use the pegLIT tool to design a suitable linker sequence [3] [2].

- Optimize PBS and RTT Length: Even with epegRNAs, the core pegRNA components need to be optimized. Test PBS lengths around 13 nt and RTT lengths of 10-16 nt. Maintain a GC content of 40-60% for the PBS [2].

- Inhibit Mismatch Repair (MMR): Combine your epegRNA with a system that temporarily inhibits MMR, such as the PE4/PE5 system (which uses a dominant-negative MLH1 protein) or the PE6/PE7 systems. This prevents the cell from rejecting the newly edited strand [8] [18].

- Consider the 3' Terminal Base: Avoid designing a pegRNA whose 3' extension begins with a C base, as it can base-pair with G81 in the sgRNA scaffold, disrupting Cas9 binding and function [2].

Problem: High Indel Byproducts

Potential Cause: The editing strategy leads to concurrent nicks on both DNA strands, which can be misinterpreted as a double-strand break.

Solution Checklist:

- Edit the PAM Site: If your edit allows, include a silent or synonymous mutation in the PAM sequence. This prevents the prime editor from re-binding and re-nicking the newly edited strand [2].

- Use the PE3b/PE5b Strategy: When employing a second nicking sgRNA (as in PE3/PE5), design it as a PE3b/PE5b system. This means the nicking sgRNA should be complementary to the edited DNA sequence, ensuring it only nicks the non-edited strand after the edit has been installed, thereby reducing double-nicking events and indel formation [8] [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing an epegRNA Expression Cassette

This protocol is adapted from methods used in rice and mammalian cell studies [3] [25].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 2: Essential Reagents for epegRNA Construction

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| pegRNA Design Tool | Software (e.g., pegFinder, PlantPegDesigner) to design spacer, RTT, and PBS sequences. |

| pegLIT Tool | Web tool for designing a non-interfering linker between the PBS and the RNA motif [3]. |

| Overlap Extension PCR | A technique to synthesize the full epegRNA fragment for cloning. |

| U6 Promoter Vector | A plasmid vector (e.g., pOsU6BbsIx2tQ1_polyT) for expressing the epegRNA in cells. |

| BbsI Restriction Site | A Type IIS restriction enzyme site used for golden gate cloning of the epegRNA sequence. |

| In-Fusion Cloning System | A seamless cloning method to insert the epegRNA fragment into the linearized vector. |

Methodology:

- Design: Using your target sequence and desired edit, design the pegRNA spacer, RTT, and PBS (e.g., 13 nt PBS, 10-16 nt RTT). Use pegLIT to generate an 8-nt linker and append your chosen protective motif (e.g., evopreQ1) to the 3' end of the linker [3] [25].

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis: Synthesize overlapping DNA oligonucleotide pairs that, when annealed, form the complete sequence: 20-nt spacer - sgRNA scaffold - RTT - PBS - 8-nt linker - RNA motif.

- Fragment Assembly: Perform an overlap extension PCR with the oligonucleotides to synthesize the full epegRNA expression cassette as a double-stranded DNA fragment.

- Vector Preparation: Digest your U6 promoter-containing destination vector with BbsI (or another suitable Type IIS enzyme) to linearize it.

- Cloning: Use the In-Fusion HD Cloning system to ligate the PCR-amplified epegRNA fragment into the linearized vector. Transform the ligation product into competent bacteria and sequence-verify positive clones [25].

Protocol 2: Evaluating epegRNA Performance in Mammalian Cells

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Culture HEK293T cells (or your cell line of interest) under standard conditions. Co-transfect the cells with two plasmids: one expressing the prime editor (e.g., PEmax) and the other expressing the epegRNA (constructed in Protocol 1). Include a control group transfected with a canonical pegRNA targeting the same site [3].

- Harvest and Analysis: Harvest cells 72 hours post-transfection. Extract genomic DNA from the cell population.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Design primers to amplify the genomic region surrounding the target site by PCR. Purify the PCR products and subject them to NGS.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the NGS data to calculate the percentage of reads containing the desired edit. Calculate the editing efficiency as (# of edited reads / # of total reads) * 100. Compare the efficiency of the epegRNA to the canonical pegRNA control. Also, calculate the edit:indel ratio to assess precision [3] [24].

Diagrams and Workflows

epegRNA Protection Mechanism

Experimental Workflow for epegRNA Testing

Optimizing Primer Binding Site (PBS) Length and Reverse Transcriptase Template (RTT) Composition

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the recommended starting lengths for PBS and RTT? Initial pegRNA designs should test a PBS length of about 13 nucleotides and an RTT length of 10–16 nucleotides [2]. For edits requiring longer RTTs, further optimization is critical, as unintended secondary structures in the pegRNA can inhibit editing [2].

Q2: How does PBS sequence composition affect editing efficiency? Primer Binding Sites with a GC content between 40% and 60% are most likely to be successful [2]. While sequences outside this range can be optimized, staying within this GC content window improves the probability of effective primer binding and editing.

Q3: Why is the first base of the pegRNA's 3' extension important? The first base of the 3' extension should not be a C. A C in this position is speculated to base-pair with a specific guanine (G81) in the gRNA scaffold, disrupting the canonical pegRNA structure and Cas9 binding, which can compromise editing efficiency [2].

Q4: How can I improve the stability of my pegRNA? Using engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) that include structured RNA motifs (like mpknot) at their 3' end can protect the pegRNA from exonucleolytic degradation and improve its stability and editing outcomes [18] [2]. Tools like pegLIT can help design linkers for these structures [2].

Q5: What strategic edits can be included in the RTT to enhance outcomes?

- Edit the PAM sequence if possible. This prevents the Cas9 nickase from re-binding and re-nicking the newly synthesized edited strand, which reduces the formation of unwanted indels [2].

- For point mutations, consider adding silent mutations to create a "bubble" of 3 or more consecutive mismatches. Cellular DNA mismatch repair (MMR) systems are less efficient at correcting these multi-base mismatches, thereby increasing the likelihood that the edit is permanently incorporated [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low Prime Editing Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Suboptimal PBS or RTT length.

Cause 2: pegRNA degradation.

Cause 3: Active DNA Mismatch Repair (MMR) rejecting the edit.

Cause 4: Inefficient resolution of the editing intermediate.

- Solution: For the PE3/PE5 systems, use a nicking sgRNA (ngRNA) on the non-edited strand. Test ngRNA binding sites located approximately 50–100 bp from the original pegRNA nick site to encourage the cell to use the edited strand as a repair template [18] [2]. Prefer the PE3b/PE5b strategy, where the ngRNA is designed to bind only after the edit is installed, reducing the chance for double-strand breaks and indels [2].

Problem: High Indel Byproducts

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Concurrent nicking of both DNA strands.

- Solution: Switch from the PE3/PE5 system to the PE3b/PE5b system. This ensures the nicking sgRNA only targets the edited DNA sequence, thereby minimizing the chance of creating a double-strand break [2]. Also, consider using next-generation prime editors like vPE or pPE, which are engineered with Cas9-nickase mutations that relax nick positioning and dramatically reduce indel errors [23].

Cause 2: Re-nicking of the edited strand.

- Solution: A key strategy is to include the PAM site in your edit. By mutating the PAM sequence in the RTT, you prevent the prime editor from recognizing and re-nicking the newly edited DNA [2].

Cause 3: Homology between pegRNA scaffold and genomic sequence.

- Solution: When using MMR-inhibiting systems (PE4/PE5), ensure the pegRNA scaffold sequence does not have significant homology to the target genomic region. This homology can lead to the unintended incorporation of parts of the scaffold into the genome [2].

Quantitative Data for PBS and RTT Optimization

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Optimal Ranges for PBS and RTT

| Parameter | Recommended Starting Point | Tested Effective Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS Length | 13 nt [2] | 8 - 16 nt [18] [12] | PBS with 40-60% GC content is most successful [2]. |

| RTT Length | 10-16 nt [2] | 10 - 30+ nt [18] | Longer templates require careful optimization to avoid secondary structures [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Optimization of pegRNA Design

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for empirically determining the optimal PBS and RTT parameters for a specific prime editing target, based on established best practices [18] [2].

Objective: To identify the most efficient pegRNA design for a specific genomic edit by testing a matrix of PBS and RTT lengths.

Materials:

- Prime editor plasmid (e.g., PEmax [26])

- Plasmid(s) for nicking sgRNA (if using PE3/PE5 systems)

- Cloning-ready backbone plasmid for pegRNA expression

- Oligonucleotides for cloning various pegRNA designs

- Tissue culture materials and transfection reagent for your cell line (e.g., HEK293T [18])

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and primers flanking the target site

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) library preparation kit and access to a sequencer [26]

Workflow Diagram: PegRNA Design Optimization

Procedure:

pegRNA Design and Cloning:

- For your specific target edit, design a library of pegRNAs that vary in PBS length (e.g., 8, 10, 13, 16 nucleotides) and RTT length (e.g., 10, 16, 22, 30 nucleotides).

- Ensure the first base of the 3' extension is not a C [2].

- Clone each pegRNA design into your chosen expression vector.

Cell Transfection:

- Culture your target cells (e.g., HEK293T) according to standard protocols.

- Co-transfect the cells with a constant amount of the prime editor plasmid (e.g., PEmax) and each individual pegRNA plasmid. Include a negative control (e.g., a non-targeting pegRNA).

- If using a PE3/PE5 system, also co-transfect a plasmid expressing a nicking sgRNA.

Harvest and Genomic DNA Extraction:

- 48-72 hours post-transfection, harvest the cells.

- Extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit, ensuring high purity and concentration for downstream PCR.

Target Locus Amplification and Sequencing:

- Design primers to amplify a ~300-500 bp region surrounding the target site.

- Perform PCR on the extracted genomic DNA from each sample.

- Prepare an NGS library from the purified PCR amplicons and sequence on an Illumina platform or equivalent to obtain deep sequencing data.

Data Analysis:

- Process the NGS data using specialized software (e.g., CRISPResso2) to align sequences to the reference genome.

- For each pegRNA variant, calculate the editing efficiency (% of reads containing the precise desired edit) and the indel rate (% of reads with insertions or deletions at the target site).

- The optimal pegRNA is the one that yields the highest editing efficiency with the lowest indel rate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Prime Editing Optimization

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Plasmids | Core editing machinery. | PEmax: Codon-optimized PE2 with enhanced nuclear localization [26]. PE6/PE7: Newer versions with compact RT or fused La protein for improved stability/efficiency [18]. |

| pegRNA Expression Vectors | To clone and express pegRNA variants. | Plasmids with U6 promoter for pegRNA expression. Some are designed for easy oligo cloning [27]. |

| MMR Inhibitor | Suppresses mismatch repair to boost editing efficiency. | MLH1dn: A dominant-negative MLH1 protein used in PE4 and PE5 systems [18] [26]. |

| Nicking sgRNA | Nicks the non-edited strand to bias repair towards the edit. | Required for PE3 and PE5 systems. Designed to bind ~50-100 bp from the pegRNA nick site [2]. |

| Stable Cell Line Generation Tools | Ensures sustained editor expression for difficult edits. | PiggyBac Transposon System: Allows stable genomic integration of large prime editor constructs [20]. |

| NGS Analysis Software | Precisely quantifies editing efficiency and byproducts. | Tools like CRISPResso2 are essential for accurate analysis of prime editing outcomes from amplicon sequencing data [26]. |

Prime editing is a versatile "search-and-replace" genome editing technology that enables precise installation of substitutions, insertions, and deletions without requiring double-strand DNA breaks or donor DNA templates [28]. The system uses a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target genomic location and encodes the desired edit through its 3' extension, which contains a primer binding site (PBS) and a reverse transcription template (RTT) [2]. Despite its promising capabilities, prime editing efficiency is significantly influenced by pegRNA design parameters, including PBS length, RTT composition, and secondary structure formation [29] [2]. Optimizing these components manually is complex and time-consuming, creating a critical need for computational tools that can streamline and enhance the design process. This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges through targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs, providing researchers with practical methodologies for improving prime editing outcomes.

Computational Tools for pegRNA Design

pegFinder: Rapid pegRNA Design and Ranking

Overview: pegFinder is a web-based tool that rapidly designs and ranks candidate pegRNAs from reference and edited DNA sequences [30]. Its algorithm incorporates sgRNA on-target and off-target scoring predictions and nominates secondary nicking sgRNAs to increase editing efficiency.

Key Features and Design Parameters:

- Input Requirements: pegFinder requires the wildtype DNA sequence (>100nt flanks recommended around the edit site) and the edited DNA sequence with identical 5' and 3' ends [30].

- Spacer Selection: The tool prioritizes sgRNA spacers whose target sites would be disrupted after prime editing and considers the distance between the nick site and desired edits [30].

- PBS and RTT Generation: pegFinder evaluates edited base positioning and GC content to generate appropriate PBS and RTT sequences of varying lengths for experimental optimization [30].

- Secondary Nicking sgRNAs: It identifies PE3 nicking sgRNAs (40-150nt away on the opposite strand) and PE3b sgRNAs that become active only after successful editing [30].

Table 1: pegFinder Design Parameters and Outputs

| Component | Design Considerations | pegFinder Output |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Spacer | Target disruption post-editing; Distance to edits | Ranked list of candidate spacers |

| Primer Binding Site (PBS) | GC content (40-60% optimal) [2] | PBS sequences of varying lengths (e.g., ~13 nt starting point) [2] [30] |

| Reverse Transcription Template (RTT) | Length, secondary structure avoidance | RTT templates of varying lengths (e.g., 10-16 nt starting point) [2] [30] |

| Cloning Oligos | Direct experimental implementation | Oligonucleotide sequences for standard plasmid vectors [30] |

pegLIT: Optimizing Linker Sequences for Structured pegRNAs

Overview: pegLIT (pegRNA Linker Identification Tool) addresses the challenge of unwanted base pairing in engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs). epegRNAs include structured RNA motifs at their 3' end, such as mpknot, to protect against degradation and improve stability [2]. pegLIT creates non-interfering nucleotide linkers between the pegRNA and these 3' motifs to minimize unwanted intra-RNA base pairing with the primer binding site, thereby enhancing editing efficiency [31] [2].

PlantPegDesigner: Application in Plant Systems

Note: Within the provided search results, no specific information was available for "PlantPegDesigner." The tools and principles discussed, particularly pegFinder, have been validated in plant systems [30], suggesting that general pegRNA design rules are applicable. For plant-specific optimization, researchers should consult specialized literature or tools.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common pegRNA Design and Experimental Issues

Low Editing Efficiency

Problem: Prime editing fails to produce the desired edit at detectable levels, or efficiency is very low.

Solutions:

- Systematically vary PBS and RTT length: Begin with a PBS of ~13 nt and an RTT of 10-16 nt, but test a range of lengths for both components as optimal parameters are context-dependent [2] [30].

- Avoid a 'C' as the first base of the 3' extension: This prevents disruptive base pairing with G81 of the gRNA scaffold, which can interfere with Cas9 binding [2].

- Edit the PAM sequence: Incorporating an edit that disrupts the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) prevents the Cas9 nickase from re-binding and re-nicking the newly synthesized strand, which can reduce indel formation [2].

- Use enhanced systems: Employ epegRNAs with tools like pegLIT to stabilize the pegRNA [2] or use advanced editor architectures like PEmax and systems with transient MMR inhibition (PE4/PE5) [28] [20].

- Validate with a positive control: Always include a well-characterized pegRNA and target site to confirm your experimental system is functioning correctly [32].

High Indel Byproduct Formation

Problem: The editing experiment results in an unacceptable frequency of insertions and deletions (indels) at the target site.

Solutions:

- Implement the PE3b/PE5b strategy: Design the nicking sgRNA to bind only after the edit is installed on the opposite strand. This reduces the chance of creating concurrent nicks that can lead to double-strand breaks and indels [2] [30].

- Disrupt the PAM: As with improving efficiency, editing the PAM sequence prevents re-nicking of the edited strand [2].

- Modulate MMR inhibition: In PE4/PE5 systems, ensure the pegRNA scaffold lacks homology to the genomic target, as MMR inhibition can otherwise promote unintended incorporation of the scaffold sequence [2].

Inefficient Editing in Specific Cell Types

Problem: Editing efficiency is satisfactory in standard cell lines (e.g., HEK293T) but low in therapeutically relevant or difficult-to-transfect cells.

Solutions:

- Optimize delivery method and expression: Use stable genomic integration of the prime editor (e.g., via piggyBac transposon system) and sustained pegRNA delivery (e.g., lentivirus) to ensure robust, long-term expression [20].

- Select highly active clones: Establish single-cell clones from stably integrated editor cells and validate for high editing activity [20].

- Use strong, ubiquitous promoters: Drive editor expression with potent promoters like CAG for high-level, consistent expression across cell types [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the optimal starting lengths for the PBS and RTT? A1: A recommended starting point is a PBS of about 13 nucleotides and an RTT of 10-16 nucleotides. However, these are not universal optima, and you should test a range of lengths (e.g., 8-15 nt for PBS, and extensions for longer RTTs) to find the most effective combination for your specific edit and genomic context [2] [30].

Q2: How can I reduce the likelihood of my edit being reversed by the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system? A2: You can design your RTT to include silent mutations near your primary edit, creating a "bubble" of 3 or more consecutive mismatches. MMR is less efficient at correcting these longer tracts of mismatched bases, which helps the desired edit to be retained [2].

Q3: When should I use a PE3/PE5 system versus a PE4/PE5 system? A3:

- PE3/PE5: Use these if you can tolerate a potentially higher indel rate and want to avoid long-term MMR inhibition. They are a good choice when a highly active nicking sgRNA is available and the edit does not generate excessive indels [28] [2].

- PE4/PE5: Prefer these when minimizing indels is a top priority, or in cell types where nicking sgRNAs are ineffective. These systems transiently inhibit MMR to boost editing efficiency [28] [2].

Q4: My pegRNA is designed correctly, but editing is still low. What other factors should I check? A4:

- Delivery efficiency: Ensure your transfection method is efficient for your cell type. Consider optimizing delivery conditions extensively [32] [20].

- Editor expression: Verify robust expression of the prime editor protein using Western blot or other methods.

- Cell health: High toxicity can reduce the number of successfully edited cells. Titrate the amounts of editor and pegRNA to find a balance between efficiency and cell viability [33] [32].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Prime Editing Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PEmax Vector | An optimized prime editor architecture with improved nuclear localization and expression. | Increasing base editing efficiency across diverse cell lines. |

| epegRNA Scaffold | A pegRNA with a structured 3' RNA motif (e.g., mpknot) for enhanced stability. | Improving editing yields, especially for challenging edits. |

| MLH1dn (MLH1 dominant-negative) | A component of PE4/PE5 systems that transiently inhibits DNA mismatch repair. | Boosting editing efficiency in MMR-proficient cell types. |

| pegLIT Tool | A computational tool for designing optimal linkers in epegRNAs. | Preventing unwanted secondary structure in complex pegRNA designs. |

| piggyBac Transposon System | A non-viral method for stable genomic integration of large DNA cargo. | Creating stable cell lines with sustained prime editor expression. |

| Lentiviral pegRNA Vectors | Viral delivery system for sustained pegRNA expression. | Enabling long-term pegRNA expression in hard-to-transfect cells. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: A computational and experimental workflow for designing and testing pegRNAs, integrating tools like pegFinder and pegLIT.

Diagram 2: The structure of a pegRNA and its key design parameters, showing which computational tools address different components.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Dual pegRNA Systems

Q1: What is a dual pegRNA (or paired pegRNA) system, and why would I use it?

A: A dual pegRNA system involves using two separate prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs) that are designed to edit the same target site. The primary goal is to significantly increase the efficiency of prime editing by having two opportunities to incorporate the desired edit. One pegRNA nicks and edits the "target" strand, while its partner nicks and edits the "non-target" strand. This dual nicking strategy encourages the cell's repair machinery to use the edited strands as templates, thereby increasing the likelihood of permanently installing the desired mutation into the genome [25].

Q2: My dual pegRNA editing efficiency is low. What are the key design principles to check?

A: Low efficiency can often be traced to pegRNA design. Focus on these critical parameters:

- PAM Availability and Orientation: The two pegRNAs must bind to opposite DNA strands and their PAMs should point outward. When using canonical SpCas9 (NGG PAM), one pegRNA should recognize an NGG PAM sequence, while its partner should recognize the complementary CCN sequence on the opposite strand [25].

- PAM Sequence for Cas9 Variants: If you are using a Cas9-NG variant (which recognizes NG PAMs) to expand targeting scope, be aware that efficiency can be highly dependent on the specific NG PAM sequence. For example, in rice, editing efficiency was particularly low when one of the pegRNAs targeted an NGC PAM [25].

- Use of Engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs): Always consider using epegRNAs, which have an engineered RNA structure (like a pseudoknot) appended to their 3' end. This modification enhances pegRNA stability by protecting it from degradation, which consistently improves editing outcomes [25].

Q3: Does using a dual pegRNA system increase the risk of generating indels?

A: While the dual pegRNA system is designed to be more efficient, the use of two nicking events does inherently increase the theoretical risk of generating small insertions or deletions (indels) if the nicks are processed into a double-strand break. However, the overall risk is still much lower than with traditional CRISPR-Cas9 which relies on creating double-strand breaks from the start [34] [18].

proPE System (engRNA/tpgRNA)

Q4: What is the fundamental difference between standard PE and the proPE system?

A: The key innovation of proPE (prime editing with prolonged editing window) is the separation of the nicking and templating functions onto two distinct RNA molecules [12]:

- Essential Nicking Guide RNA (engRNA): This is a standard sgRNA that directs the prime editor protein to nick the target DNA site. It is responsible for initiating the editing process.

- Template Providing Guide RNA (tpgRNA): This RNA contains the Primer Binding Site (PBS) and Reverse Transcription Template (RTT), but it has a truncated spacer sequence (11-15 nucleotides). This truncation makes the Cas9 protein catalytically inactive at the tpgRNA's binding site, meaning it binds DNA but does not nick it. Its sole purpose is to position the editing template near the nick created by the engRNA.

This separation of labor overcomes several bottlenecks inherent to standard PE where a single pegRNA must perform both functions [12].

Q5: When should I consider using the proPE system over a standard dual pegRNA approach?

A: The proPE system is particularly advantageous in the following scenarios [12]:

- When you need to make edits that fall outside the typical editing window of standard PE.

- When you are targeting a site where standard PE consistently shows very low efficiency (<5%).

- When you require allele-specific editing, as the requirement for two target sites (one for the engRNA and one for the tpgRNA) increases specificity.

- When you want to minimize potential inhibition from degraded pegRNAs, as the system is less susceptible to this issue.

Q6: How do I design a tpgRNA for the proPE system?

A: The design of the tpgRNA is critical for proPE success. The most important parameter is its spacer length.

- Spacer Length: Design the tpgRNA with a truncated spacer of 10 to 15 nucleotides. A length of 15 nucleotides is sufficient to render SpCas9 inactive for DNA cleavage while still allowing for stable binding to the target site. Effective editing has been observed with spacers as short as 5 nucleotides, but 10-15 nt is the recommended range [12].

- Binding Site: The tpgRNA should bind to a DNA sequence in the vicinity of the nick site created by the engRNA.

Q7: I've set up my proPE system, but editing is still inefficient. What can I optimize?

A: If efficiency is low, titrate the amount of your engRNA. Unlike in standard PE, the amount of nicking activity (governed by the engRNA) and templating activity (governed by the tpgRNA) can be independently controlled in proPE. Research has shown that increasing the amount of engRNA only improves efficiency up to a point, after which it can decline, likely due to re-nicking of the edited DNA. Therefore, testing two or three different concentrations of engRNA plasmid while keeping the tpgRNA amount constant is a key optimization step [12].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent studies on dual pegRNA and proPE systems.

Table 1: Dual pegRNA Efficiency with Different Cas9 Variants in Rice

This table compares the editing efficiency of a wild-type SpCas9 (PE-wt) with a broad-range SpCas9-NG (PE-NG) when used in a dual epegRNA setup [25].

| Cas9 Editor | PAM Recognized | Required PAM Configuration for Dual PegRNAs | Key Finding on Editing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE-wt | NGG | One NGG and one CCN (outward-facing) | Can be highly efficient even when targeting a distal PAM site. |

| PE-NG | NG | Two NG PAMs (outward-facing) | Efficiency is highly variable and can be significantly lower than PE-wt when one of the paired epegRNAs targets an NGC PAM. No significant difference from PE-wt when using NGA or NGT PAMs. |

Table 2: proPE System Performance vs. Standard Prime Editing

This table summarizes the performance enhancements offered by the proPE system as reported in the foundational study [12].

| Performance Metric | Standard PE | proPE System | Enhancement & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Efficiency (for low-performing PE sites) | < 5% | Up to 29.3% | Represents an average 6.2-fold increase for edits where standard PE is inefficient. |

| Functional tpgRNA Spacer Length | Not Applicable (single pegRNA) | 10-15 nucleotides (effective editing detectable with spacers as short as 5 nt) | The truncated spacer is essential to make the Cas9 complex bound to tpgRNA catalytically inactive. |

| Key Tunable Parameter | Single pegRNA concentration | engRNA concentration | proPE allows independent optimization of nicking (engRNA) and templating (tpgRNA). Editing efficiency peaks at an optimal engRNA level. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Dual epegRNA System in Rice

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully used dual epegRNAs for precise gene modification in rice [25].

1. Design and Cloning:

- Design Tool: Use specialized software like pegFinder, PlantPegDesigner, or pegLIT to design your paired epegRNAs.

- epegRNA Structure: Ensure each epegRNA is engineered to include an 8-nucleotide linker and an RNA pseudoknot sequence (e.g., tevopreQ1) at its 3' end to enhance stability.

- Vector Construction: Clone the two epegRNA expression cassettes concomitantly into your chosen binary vector containing the prime editor (e.g., PE-wt or PE-NG). The vector should use a plant-codon-optimized editor and a suitable promoter (e.g., ZmUbi).

2. Plant Transformation and Selection:

- Plant Material: Use 4-week-old calli derived from rice embryo scutellum (e.g., cultivars Nipponbare or Yamadawara).

- Transformation: Perform Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (strain EHA105) with a 3-day co-cultivation period.

- Selection: Transfer calli to selection medium containing hygromycin B for 2-3 weeks to select for antibiotic-resistant clones.

3. Analysis of Editing Efficiency:

- DNA Extraction: Perform rapid DNA extraction from individual, clonally propagated transgenic calli.

- Genotyping: Use PCR to amplify the target genomic region and perform Sanger sequencing of the products.

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate the PE frequency as the percentage of transgenic calli lines in which the desired mutation is detected by sequencing.

Protocol 2: Validating and Optimizing the proPE System in Human Cells

This protocol outlines the key steps for setting up and testing the proPE system, based on the original publication [12].

1. Component Design and Preparation:

- engRNA Design: Design a standard sgRNA that targets your genomic site of interest and will direct the prime editor to create a nick.

- tpgRNA Design: Design a second guide RNA that contains the PBS and RTT encoding your desired edit. Crucially, its spacer sequence must be truncated to 11-15 nucleotides to prevent DNA cleavage.

- Plasmid Preparation: Prepare separate plasmids for the expression of the prime editor protein, the engRNA, and the tpgRNA.

2. Transfection and Titration:

- Cell Line: Use HEK293T cells or your cell line of interest.

- Initial Transfection: Co-transfect cells with a constant, saturating amount of the tpgRNA plasmid and the prime editor plasmid, along with a series of different concentrations of the engRNA plasmid (e.g., low, medium, high).

- Control: Always include a control with a non-targeting tpgRNA to confirm that editing is specific to the combination of both engRNA and tpgRNA.

3. Editing Assessment:

- Genomic DNA Analysis: After 72 hours, extract genomic DNA and amplify the target locus by PCR.

- Deep Sequencing: Perform amplicon deep sequencing to quantitatively assess the precise editing efficiency and to screen for any indel byproducts.

- Data Analysis: Compare the editing efficiency across the different engRNA concentration conditions to identify the optimal level that maximizes correct edits while minimizing errors.

System Architecture Diagrams

Dual pegRNA Editing Mechanism

proPE System Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced Prime Editing Systems

| Reagent / Component | Function in Experiment | Key Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9-NG Nickase | Expands the targeting scope of PE by recognizing NG PAMs instead of only NGG. | Essential for dual pegRNA strategies when NGG PAMs are not available. Be aware that efficiency can vary with the specific NG sequence (e.g., NGC can be low-efficiency) [25]. |

| Engineered pegRNA (epegRNA) | The guide RNA that directs editing and contains the template; enhanced for stability. | Should include a 3' RNA pseudoknot structure (e.g., tevopreQ1 or mpknot) to prevent degradation and improve editing efficiency [25]. |

| proPE System Plasmids | Plasmid DNA for expressing the engRNA and tpgRNA components. | The tpgRNA plasmid must be designed with a truncated spacer (10-15 nt). Multiple engRNA plasmid concentrations should be tested for optimal results [12]. |

| PiggyBac Transposon System | Enables stable genomic integration of the prime editor for sustained expression. | A non-viral delivery method ideal for creating stable cell lines with high, persistent editor expression, which can boost editing rates [35]. |

| MLH1dn (MLH1 dominant-negative) | A mismatch repair (MMR) inhibitor. | Co-expression with the prime editor can increase editing efficiency by inhibiting the MMR pathway, which often corrects PE-mediated edits back to the original sequence [18] [35]. |

Overcoming pegRNA Design Challenges and Boosting Editing Efficiency

Mismatch Repair Inhibition: The Core Concept

What is the fundamental mechanism by which inhibiting the Mismatch Repair (MMR) pathway with MLH1dn improves prime editing efficiency?

The MMR system, specifically the MutSα–MutLα complex, actively recognizes and rejects the heteroduplex DNA structure formed during prime editing, thereby suppressing desired edit outcomes [36] [8]. The heteroduplex contains a mismatch between the newly synthesized, edited DNA strand and the original, unedited strand [8]. The MMR machinery tends to excise the edited strand, using the original, unedited strand as a template for repair, effectively reversing the prime edit [36] [8]. Using a dominant-negative version of the MLH1 protein (MLH1dn) transiently inhibits this pathway. MLH1dn is a truncated mutant (lacking the D754–756 endonuclease domain) that disrupts the function of the native MutLα complex [36] [37]. This inhibition prevents the removal of the edited DNA flap, giving cellular processes a better chance to permanently incorporate the desired genetic change [8].

Table 1: Key MMR Components and Their Role in Prime Editing

| Protein/Complex | Role in Native MMR | Effect on Prime Editing |

|---|---|---|