Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery: A Comprehensive Guide for Efficient Plant Genome Editing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Agrobacterium-mediated delivery for CRISPR/Cas reagents in plants, a cornerstone technique for functional genomics and crop improvement.

Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery: A Comprehensive Guide for Efficient Plant Genome Editing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Agrobacterium-mediated delivery for CRISPR/Cas reagents in plants, a cornerstone technique for functional genomics and crop improvement. We explore the foundational principles of this method, from the basic biology of Agrobacterium to the components of CRISPR/Cas systems. The manuscript details advanced methodological workflows, including ternary vector systems and protocols for specific crops like wheat and Nicotiana alata. A dedicated section addresses common bottlenecks and optimization strategies, such as enhancing transformation efficiency with developmental regulators and achieving transgene-free editing. Finally, we present a comparative analysis with other delivery methods (biolistics, RNP transfection) and outline robust validation techniques for confirming edits and assessing off-target effects. This guide is tailored for researchers and scientists seeking to implement or optimize this powerful technology in their plant genome editing pipelines.

The Core Principles of Agrobacterium and CRISPR Synergy

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a soil-borne, Gram-negative bacterium renowned for its natural ability to transfer genetic material into plant genomes, a process that has been harnessed to make it a cornerstone of plant genetic engineering [1]. This pathogen causes crown gall disease in plants by transferring a segment of DNA (T-DNA) from its Tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the host plant cell, where it integrates into the plant's nuclear DNA [2] [3]. The resulting expression of T-DNA genes leads to the production of plant hormones that cause tumor formation and opines that the bacterium can utilize as a nutrient source [1].

The molecular mechanism of T-DNA transfer is a sophisticated, multi-step process triggered by plant signals. The core steps are as follows:

- Signal Recognition and vir Gene Induction: Upon sensing plant wound compounds, such as acetosyringone, Agrobacterium activates the expression of its virulence (vir) genes located on the Ti plasmid [1].

- T-DNA Processing: The vir gene products nick the T-DNA at its left and right border sequences. The excised single-stranded T-DNA (T-strand) is coated and protected by VirE2 proteins [3].

- Formation of the T-Complex: The single-stranded T-DNA, bound to the VirD2 pilot protein at its 5' end and covered by VirE2 proteins, forms the T-complex ready for export [2].

- Transfer into the Host Cell: The T-complex is transferred into the plant cell cytoplasm through a bacterial Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) encoded by the virB operon [1].

- Nuclear Import and Integration: Inside the plant cell, the T-complex is trafficked into the nucleus. The VirD2 protein is thought to interact with host proteins, such as the TATA box-binding protein and a nuclear protein kinase, to facilitate this process [2]. The T-DNA then integrates into the plant genome, a process that can involve double-stranded intermediates and often targets double-strand break repair sites [2].

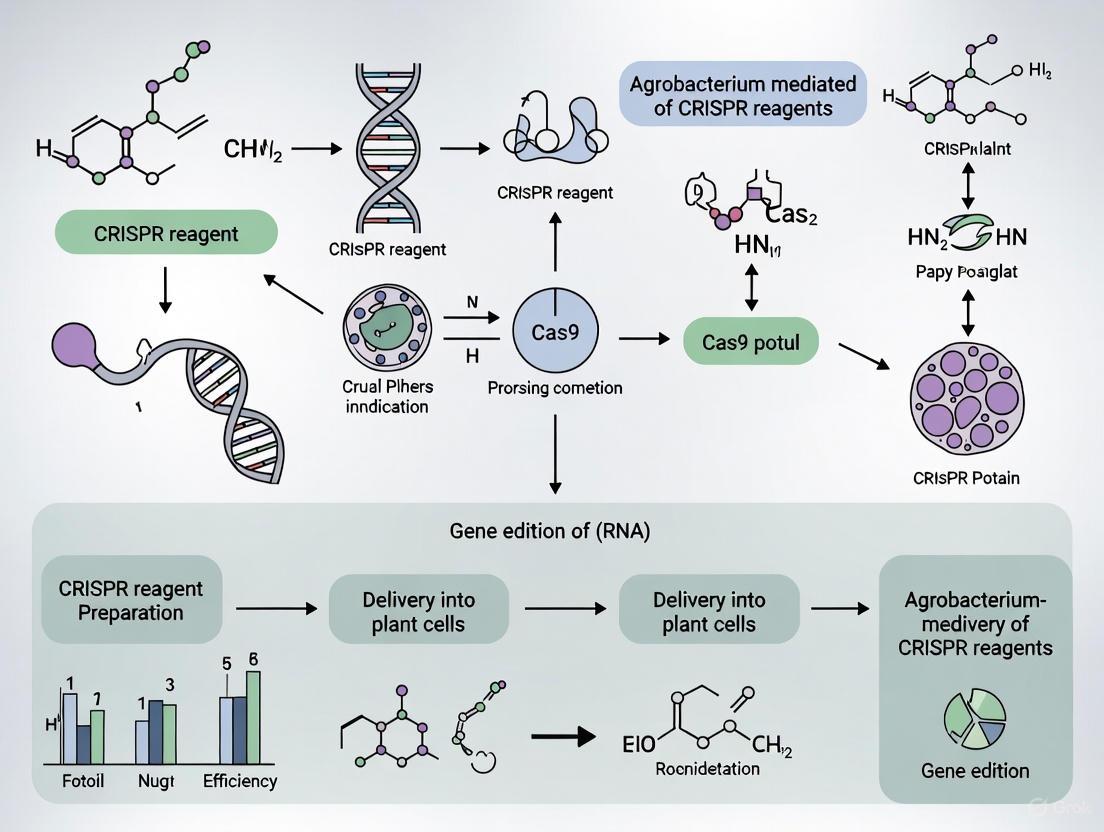

The following diagram illustrates this complex transfer process and its integration with CRISPR/Cas9 delivery workflows.

Application Notes: Delivering CRISPR/Cas9 Reagents

The natural DNA transfer machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens has been ingeniously repurposed to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing components into plant cells. This application is revolutionizing plant functional genomics and molecular breeding by enabling precise genetic modifications.

Key Advancements and Efficiencies

Table 1: Recent Applications of Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery in Plants

| Plant Species | Target Gene | Edited Trait | Transformation/Editing Efficiency | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraxinus mandshurica (Manchurian ash) [4] | FmbHLH1 | Drought tolerance | 18% of induced clustered buds were gene-edited | Established first CRISPR system for this tree; knockout increased drought resistance. |

| Platycodon grandiflorus (Balloon flower) [5] | chr2.2745 | Functional genomics | 16.70% genome editing efficiency | Combined with morphogenic regulators to boost regeneration to 21.88%. |

| Elymus nutans (Alpine grass) [5] | EnTCP4 | Delayed flowering, Drought tolerance | 19.23% editing efficiency | First stable transformation system for this grass; enabled molecular breeding. |

| Melia volkensii (African timber tree) [5] | M24::eGFP (reporter) | Foundation for future editing | Transformation established | Pioneered method for future CRISPR applications in this drought-resistant species. |

| Tomato [5] | Multiple gene families | Fruit development, flavor, disease resistance | ~1300 independent lines created | Used genome-wide multi-targeted sgRNA library to overcome functional redundancy. |

Protocol: Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of Fraxinus mandshurica

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, details the successful generation of FmbHLH1 knockout plants to study drought tolerance [4].

I. Plant Material Preparation

- Explant Source: Excise embryos from surface-sterilized seeds of Fraxinus mandshurica.

- Germination: Culture sterile embryos on Woody Plant Medium (WPM) solid medium (WPM + 20 g/L sucrose + 6 g/L agar, pH 5.8) without hormones.

- Growth Conditions: Maintain plantlets at 24–26 °C, 70–75% relative humidity, with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle (400 μmol/m²/s light intensity) [4].

II. Vector Construction and Agrobacterium Preparation

- Target Selection: Input the target gene sequence (FmbHLH1 used in the cited study) into a target design website (e.g., http://skl.scau.edu.cn/targetdesign/) to generate specific knockout targets.

- Vector Assembly: Clone synthesized oligonucleotide cassettes into a binary CRISPR/Cas9 vector (e.g., pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N) behind a suitable promoter like AtU6-26.

- Agrobacterium Transformation: Introduce the recombinant vector into an appropriate Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., EHA105) via electroporation or freeze-thaw. Select positive colonies on LB agar with appropriate antibiotics [4].

III. Inoculation and Co-cultivation

- Bacterial Culture: Grow the transformed Agrobacterium in liquid LB medium at 28 °C until the OD₆₀₀ reaches between 0.5 and 0.8.

- Centrifugation: Pellet the bacteria by centrifugation at 1500 g for 10 min and resuspend in an inoculation medium.

- Infection: Infect the sterile plantlets or explants with the bacterial suspension. The study optimized both Agrobacterium concentration and infection duration for maximal efficiency [4].

IV. Selection and Regeneration

- Selection Medium: Transfer infected explants to a selective WPM solid medium containing antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin at a lethal concentration determined empirically, found to be between 20-70 mg/L for F. mandshurica) to inhibit Agrobacterium growth and select for transformed plant cells.

- Clustered Bud Induction: Induce the formation of clustered buds from the transformed growing points by supplementing the media with specific hormones at optimized concentrations.

- Screening: Screen the induced buds for editing events. In the cited study, 18% of the randomly selected clustered buds were confirmed to be gene-edited, validating the system's effectiveness [4].

V. Analysis of Transgenic Plants

- Molecular Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from putative transgenic lines. Use PCR and sequencing to confirm the presence of CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations at the target locus.

- Phenotypic Analysis: For functional gene studies (e.g., FmbHLH1), conduct phenotypic analyses. The cited study evaluated drought tolerance by measuring physiological indicators like reactive oxygen species scavenging ability and osmotic adjustment [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Components / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strain | Engineered to deliver T-DNA containing CRISPR constructs. Hypervirulent strains can increase efficiency. | EHA105, AGL1, LBA4404. Strain AGL1 is noted for hypervirulence [6]. |

| Binary Vector System | Carries the genetic cargo between E. coli and Agrobacterium. Houses CRISPR/Cas9 genes and gRNA expression cassettes. | pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N vector [4]. Contains plant and bacterial origins of replication, selectable markers. |

| Culture Media | For growing and inducing Agrobacterium, and for regenerating transformed plants. | LB, YEB, or AB-MES for bacteria; WPM or MS1 solid medium for plant culture and selection [4] [6]. |

| Vir Gene Inducers | Chemical signals that activate the vir genes on the Ti plasmid, initiating T-DNA transfer. | Acetosyringone (200 μM used in Arabidopsis suspension cell transformation) [6]. |

| Selection Agents | To eliminate non-transformed plant cells and isolate editing events. | Antibiotics like kanamycin (20-70 mg/L for F. mandshurica [4]); herbicides depending on the resistance marker used. |

| Hormone Supplements | To induce callus formation and regenerate whole plants from transformed cells. | Cytokinins (e.g., 6-Benzylaminopurine/BAP), Auxins (e.g., 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid/2,4-D) [6]. |

Advanced Experimental Workflow: From Transformation to Analysis

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive journey of creating and analyzing a gene-edited plant line using Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery, integrating steps from the protocol above.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is continuously evolving, with several emerging technologies poised to enhance its utility for CRISPR/Cas9 delivery further.

- Ternary Vector Systems: These systems incorporate accessory virulence genes and immune suppressors on a separate plasmid, working alongside standard binary vectors. This innovation can overcome the intrinsic transformation barriers of recalcitrant crops, achieving 1.5- to 21.5-fold increases in stable transformation efficiency in species like maize, sorghum, and soybean [7].

- Strain Engineering via INTEGRATE: Advanced CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems, such as INTEGRATE, enable precise genome engineering of Agrobacterium itself. This allows for the creation of optimized chassis strains, for example, by deleting the T-DNA from the root-inducing (Ri) plasmid of A. rhizogenes K599 to "disarm" it or by creating auxotrophic mutants (e.g., thymidine auxotrophy) for improved biosafety and control [1].

- Transformation Simplification: Novel methods are being developed to bypass the need for complex tissue culture. Techniques like the Leaf-Cutting Transformation (LCT) for Jonquil and similar plants allow for transgenic operations without aseptic procedures, significantly streamlining the process for amenable species [8].

- Protoplast Transfection as a Validation Tool: For species with low transformation and regeneration efficiency, such as pea (Pisum sativum L.), PEG-mediated transfection of protoplasts provides a high-throughput platform for rapidly validating the efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 reagents in vivo before undertaking stable transformation, saving considerable time and resources [9].

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, providing an unprecedented ability to precisely edit genomes across diverse organisms. For plant research, coupling this technology with Agrobacterium-mediated delivery has become a predominant method for introducing CRISPR reagents into plant cells [10]. This Agrobacterium-based approach utilizes the bacterium's natural ability to transfer DNA into plant genomes, offering a reliable means to achieve stable integration and expression of CRISPR components [7]. A comprehensive understanding of the three core components—the guide RNA (gRNA), the Cas nuclease, and the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM)—is fundamental to designing successful experiments. This protocol deconstructs the CRISPR/Cas9 system within the context of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, providing detailed methodologies for researchers to effectively harness this powerful technology for plant genome engineering.

Core Component 1: The Guide RNA (gRNA)

The guide RNA is a synthetic RNA molecule that directs the Cas nuclease to a specific genomic location. It consists of two primary parts: the scaffold sequence, necessary for Cas9 binding, and a user-defined ~20-nucleotide spacer that defines the genomic target to be modified [11].

gRNA Design Considerations

- Specificity: The targeting sequence must be unique compared to the rest of the genome to minimize off-target effects [11].

- Seed Sequence: An 8–10 base pair region at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence is critical for initial DNA annealing; mismatches here typically inhibit cleavage [11].

- Multiplexing: Delivering multiple gRNAs using a single plasmid ensures all are expressed in the same cell, enabling complex edits. Most multiplex systems can target 2–7 genetic loci from a single vector [11].

Core Component 2: The Cas Nuclease

The Cas nuclease is the enzyme that creates the double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA. The most commonly used nuclease is SpCas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes [11]. The resulting DSB is repaired by one of two cellular pathways [11]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An efficient but error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels), leading to gene knockouts.

- Homology Directed Repair (HDR): A less efficient, high-fidelity pathway that uses a homologous DNA template for precise repair, enabling specific gene edits.

Engineered Cas9 Variants for Enhanced Specificity and Flexibility

| Cas9 Variant | Key Features and Improvements |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Nickase (Cas9n) | D10A mutation; cuts only one DNA strand; requires two adjacent nickases for a DSB, increasing specificity [11]. |

| dead Cas9 (dCas9) | D10A and H840A mutations; no nuclease activity; used for targeted gene regulation or fluorescent imaging when fused to effectors [11] [12]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9s (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) | Engineered to reduce off-target editing by weakening non-specific DNA interactions [11]. |

| PAM-Flexible Cas9s (e.g., xCas9, SpRY) | Recognize non-canonical PAM sequences (e.g., NG, NGN), expanding the range of targetable genomic sites [11]. |

Core Component 3: The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM)

The PAM is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR system [13]. It is absolutely required for Cas nuclease activity and serves as a binding signal, enabling the nuclease to distinguish between foreign DNA (a valid target) and the bacterium's own CRISPR array (self-DNA) [13] [14].

PAM Sequences for Different Cas Nucleases

The PAM requirement is a key factor in determining which genomic locations can be targeted. The table below summarizes PAM sequences for various nucleases.

Table 1: Common CRISPR Nucleases and Their PAM Sequences

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| NmCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| Cas12i2Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| Cas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

Agrobacterium-Mediated Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a naturally occurring soil bacterium capable of transferring DNA (T-DNA) from its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant genome. This mechanism has been co-opted to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 components into plant cells [10].

Key Advantages

- High Editing Efficiency: Demonstrated to achieve up to 100% editing efficiency in some plant cultivars like Cavendish banana [10].

- Broad Applicability: Successfully used in a wide range of plants, including recalcitrant monocot crops and woody species like Citrus sinensis and Populus [10] [5].

- Stable Integration: Facilitates single-copy, stable integration of the T-DNA containing the CRISPR construct [10].

Experimental Protocol: Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation

This protocol outlines the key steps for delivering CRISPR/Cas9 reagents into plants using Agrobacterium.

Materials and Reagents

- Binary vector containing Cas9 and gRNA expression cassette(s)

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101)

- Appropriate plant explants (e.g., calluses, leaves, floral organs)

- Plant tissue culture media (co-cultivation, selection, regeneration)

- Antibiotics for bacterial and plant selection

Procedure

- Vector Construction: Clone your sequence-specific gRNA(s) and a Cas9 expression cassette (often codon-optimized for plants) into a binary T-DNA vector.

- Agrobacterium Transformation: Introduce the recombinant binary vector into your chosen Agrobacterium strain via electroporation or freeze-thaw transformation.

- Plant Co-cultivation:

- Grow the transformed Agrobacterium to log phase.

- Immerse the target plant explants in the Agrobacterium suspension for a defined period.

- Blot the explants dry and co-cultivate them on solid medium for 2-3 days to allow T-DNA transfer.

- Selection and Regeneration:

- Transfer explants to selection media containing antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium and select for plant cells that have integrated the T-DNA.

- Induce shoot and root formation from the transformed tissue on regeneration media.

- Molecular Analysis:

- Regenerate whole plants from the selected tissue.

- Validate genetic modifications using PCR, sequencing, and other assays to confirm the presence of edits and assess for off-target effects.

Diagram 1: Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR delivery workflow.

Advanced Applications: Visualization with CRISPRainbow

Beyond gene editing, catalytically inactive dCas9 can be used for visualizing genomic loci in living cells. The CRISPRainbow system engineers the gRNA scaffold to include unique RNA hairpins (e.g., MS2, PP7, boxB) that recruit differently colored fluorescent proteins [12]. This allows for multicolor labeling of up to six chromosomal loci in live cells, enabling researchers to study nuclear organization and chromosome dynamics in real time [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Plant Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Ternary Vector Systems | Enhances transformation efficiency in recalcitrant crops by delivering accessory virulence genes [7]. |

| Multiplex gRNA Vectors | Allows simultaneous expression of multiple gRNAs from a single plasmid for complex genome edits [11]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Reduces off-target effects while maintaining robust on-target activity [11]. |

| PAM-Flexible Cas Enzymes (e.g., SpRY) | Expands the targetable genome space by recognizing non-NGG PAM sequences [11] [13]. |

| dCas9-Fluorescent Protein Fusions | Enables live-cell imaging of genomic loci for studies of nuclear architecture [15] [12]. |

| Codon-Optimized Cas9 | Improves Cas9 expression and editing efficiency in plant cells [10]. |

| Morphogenic Regulators (e.g., Wus2, BBM) | Co-delivered to enhance regeneration efficiency, particularly in difficult-to-transform species [5]. |

The synergistic application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system with Agrobacterium-mediated delivery has created a powerful and accessible platform for plant genome engineering. The continuous refinement of its core components—through improved gRNA design, high-fidelity and PAM-flexible Cas enzymes, and optimized transformation protocols—is steadily overcoming the biological barriers in recalcitrant crop species. By following the detailed protocols and utilizing the reagent toolkit outlined in this document, researchers can systematically design and execute CRISPR experiments, accelerating the development of improved crop varieties to meet the challenges of global food security.

The revolutionary potential of CRISPR-based genome editing in plant biology and crop improvement is undeniable, offering unprecedented precision for functional genomics and the development of improved cultivars. However, the efficient delivery of CRISPR reagents into plant cells remains a significant bottleneck in plant genetic engineering [16]. The rigid plant cell wall presents a formidable barrier to the entry of foreign biomolecules, and many plant species have complex genome structures characterized by polyploidy and genomic rearrangements [16]. Among the various delivery methods available, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation has emerged as a preferred vehicle for CRISPR reagent delivery due to its unique combination of efficiency, reliability, and practical advantages [17] [18].

This Application Note examines the scientific and technical foundations underpinning the preference for Agrobacterium-mediated delivery systems in plant CRISPR workflows. We explore the methodological advances that have solidified its position, provide detailed protocols for implementation, and contextualize its role within the broader landscape of plant biotechnology. While newer technologies such as nanoparticle vectors and viral delivery systems continue to develop, Agrobacterium-based methods currently offer the most robust and widely adopted platform for achieving stable genetic modifications in a diverse range of plant species [17] [16].

Comparative Delivery Mechanisms in Plant Biotechnology

The Delivery Method Spectrum

CRISPR reagent delivery in plants primarily employs three principal methodologies: Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, biolistic particle delivery, and protoplast transfection. Each system possesses distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different applications and plant species [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Major CRISPR Delivery Methods in Plants

| Delivery Method | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium-mediated | Low transgene copy number; Stable integration; Reliable expression; Cost-effective [19] [16] | Limited host range; Tissue culture dependency; Somaclonal variations [16] | Stable transformation; Species within host range |

| Biolistic/Particle Bombardment | Genotype-independent; Broad species range; Delivers diverse cargo (DNA, RNA, RNP) [20] | High transgene copy number; Tissue damage; Equipment cost; Complex insertion patterns [20] [16] | Recalcitrant species; DNA-free editing (RNP delivery) |

| Protoplast Transfection | High efficiency; DNA-free editing possible; Genotype-flexible [16] | Regeneration challenges; Species-specific protocols; Technical expertise required [16] | DNA-free mutants; Species with established protoplast systems |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Recent technological advancements have significantly improved the performance of delivery systems. The development of the Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB) for biolistic delivery, for instance, has demonstrated a 22-fold enhancement in transient transfection efficiency and a 4.5-fold increase in CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein editing efficiency in onion epidermis [20]. Similarly, ternary vector systems for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation have achieved remarkable 1.5- to 21.5-fold increases in stable transformation efficiency in previously recalcitrant crops like maize, sorghum, and soybean [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Efficiency Metrics of Advanced Delivery Systems

| Delivery System | Innovation | Efficiency Gain | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biolistic Delivery | Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB) | 22x transient transfection; 4.5x RNP editing [20] | Onion epidermis |

| Biolistic Delivery | Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB) | 10x stable transformation frequency [20] | Maize B104 immature embryos |

| Agrobacterium System | Ternary Vector Systems | 1.5-21.5x stable transformation [7] | Recalcitrant crops (maize, soybean) |

| Agrobacterium Protocol | Developmental Regulators | 37.5-60.22% callus induction [19] | Maize inbred lines |

| Agrobacterium Protocol | Developmental Regulators | 6-12x transformation efficiency [19] | Wild tomato |

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation: Core Mechanisms and Workflow

The Molecular Basis of T-DNA Transfer

Diagram: Agrobacterium T-DNA Transfer and CRISPR Delivery Workflow

The fundamental mechanism of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation involves the natural ability of Agrobacterium tumefaciens to transfer a specific segment of DNA (T-DNA) from its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant genome [1]. In engineered strains for biotechnology applications, the disarmed T-DNA region carries CRISPR-Cas9 expression cassettes rather than the native oncogenes [1] [16]. The process initiates when the bacterium detects phenolic compounds released from wounded plant tissues, triggering the expression of virulence (vir) genes [1]. These vir genes facilitate T-DNA processing and delivery into plant cells through a Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) [1]. Once inside the plant nucleus, the T-DNA integrates into the genome, enabling stable expression of CRISPR components [16].

Advanced Vector Systems and Strain Engineering

The development of ternary vector systems represents a significant advancement in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation technology. Unlike traditional binary vectors, these systems incorporate accessory virulence genes and immune suppressors that overcome intrinsic transformation barriers in recalcitrant crops [7]. This innovation has dramatically expanded the effective host range of plant genetic engineering, enabling efficient transformation of species previously resistant to Agrobacterium-mediated methods [7].

Concurrent advances in Agrobacterium strain engineering have further enhanced the utility of this delivery system. The INTEGRATE system, a CRISPR RNA-guided transposase system, enables precise genomic modifications in Agrobacterium strains themselves, facilitating the development of auxotrophic mutants with improved biosafety profiles [1]. These engineered strains, such as those with thymidine auxotrophy, cannot survive outside laboratory conditions without supplementation, addressing concerns about environmental release [1].

Application Notes: Protocol for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery in Rice

Experimental Workflow and Reagent Solutions

Diagram: Rice Transformation and Genome Editing Protocol

This protocol outlines an optimized method for Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 delivery in recalcitrant rice genotypes, achieving high transformation efficiency in a relatively short period [18]. The method addresses the poor response to tissue culture that often limits genome editing in these genotypes.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Rice Transformation

| Reagent/Component | Function | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector | Carries CRISPR-Cas9 expression cassette | Typically contains plant codon-optimized Cas9, sgRNA expression unit |

| Agrobacterium Strain | T-DNA delivery vehicle | EHA105, AGL1, or LBA4404 disarmed strains [18] [1] |

| Explant Source | Target tissue for transformation | Immature embryos or calli induced from mature seed [18] |

| Selection Agents | Identification of transformed tissue | Antibiotics (e.g., hygromycin) or herbicides [18] [19] |

| Developmental Regulators | Enhance regeneration efficiency | WUS, BBM, PLT genes co-expressed to overcome genotype limitations [19] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Vector Construction and Agrobacterium Preparation

- CRISPR Construct Design: Clone species-specific sgRNA expression cassette into a binary vector containing a plant codon-optimized Cas9 nuclease driven by appropriate promoters (e.g., CaMV 35S or Ubiqutin) [18] [16].

- Agrobacterium Transformation: Introduce the binary vector into disarmed Agrobacterium strains (e.g., EHA105) via electroporation or freeze-thaw method [18].

- Culture Preparation: Inoculate a single colony into liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics and grow to OD₆₀₀ = 0.4-0.6 at 28°C with shaking [18].

Plant Transformation and Regeneration

- Explant Preparation: Isolate immature embryos (1.0-1.5 mm) from rice seeds and precondition on callus induction medium for 3-5 days [18].

- Inoculation: Immerse explants in Agrobacterium suspension for 15-30 minutes with gentle agitation [18].

- Co-cultivation: Transfer inoculated explants to filter paper over co-cultivation medium and incubate at 22-25°C for 2-3 days in darkness [18].

- Selection and Regeneration:

- Transfer explants to selection medium containing antibiotics to inhibit Agrobacterium growth and select for transformed plant cells [18].

- Subculture every 2 weeks to fresh selection medium until embryogenic calli form [18].

- Transfer putative transgenic calli to regeneration medium to induce shoot and root formation [18] [19].

- Plant Recovery: Transfer regenerated plantlets to rooting medium, then to soil in controlled environment conditions [18].

Molecular Verification and Editing Assessment

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from regenerated plant leaves using CTAB or commercial kits [18].

- Mutation Detection: Use restriction enzyme assays, PCR/sequencing, or next-generation sequencing to identify CRISPR-induced mutations at target loci [5].

- Transgene Copy Number Analysis: Employ Southern blotting or digital PCR to determine T-DNA copy number and identify single-copy events [18].

Emerging Innovations and Future Perspectives

Integration of Developmental Regulators

A significant advancement in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is the incorporation of developmental regulators (DRs) to enhance regeneration efficiency. Key genes such as WUSCHEL (WUS), BABY BOOM (BBM), and PLETHORA (PLT) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in promoting plant regeneration across diverse species [19]. For instance, co-expression of BBM and WUS2 has significantly boosted transformation efficiency in difficult-to-transform species like maize, rice, and sorghum [19]. Similarly, TaWOX5 (a WUS family gene in wheat) has improved transformation efficiency up to 75.7-96.2% in easily transformable varieties and 17.5-82.7% in difficult-to-transform varieties [19].

Viral Vectors and DNA-Free Approaches

Recent research has explored the combination of Agrobacterium with viral vectors to enhance CRISPR delivery efficiency. The Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) has been successfully employed as a viral vector for CRISPR reagent delivery, with TRV components introduced into T-DNA regions of Agrobacterium and infiltrated into transgenic plants expressing Cas9 [16]. This approach leverages the systemic movement of viruses within plants to achieve wider distribution of editing components [16].

For applications requiring DNA-free edited plants, Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression offers a viable pathway. By regenerating plants without employing selection pressure, researchers can recover transgene-free edited events, which is particularly valuable for vegetatively propagated plants where segregating out integrated transgenes through crossing is not feasible [16].

Ternary Vector Systems and Expanded Host Range

The development of ternary vector systems represents one of the most promising directions for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. These systems have demonstrated remarkable success in overcoming the biological barriers that previously limited transformation in recalcitrant species [7]. Future innovations are likely to focus on expanding these capabilities further, including transient delivery of morphogenic factors to enhance regeneration and organelle-targeted transformation for broader genetic modifications [7].

Additionally, ongoing refinement of Agrobacterium engineering—such as developing auxotrophic strains for improved biosafety and optimizing secretion systems for enhanced protein delivery—presents exciting opportunities for advancing plant biotechnology [7] [1]. These developments are reshaping the landscape of plant genetic engineering, bridging the gap between transformation efficiency and targeted genome modifications to drive the development of more resilient and high-performing crops [7].

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation remains the preferred vehicle for CRISPR delivery in plants due to its unique combination of biological efficiency, practical reliability, and continuous innovation. The method's ability to generate low-copy-number integration events, coupled with advances in vector design, strain engineering, and regeneration enhancement through developmental regulators, has maintained its relevance in an evolving technological landscape. While challenges remain—particularly regarding host range limitations and tissue culture dependencies—the integration of ternary vector systems, viral components, and DNA-free approaches continues to expand the capabilities of this powerful delivery platform. As plant biotechnology advances toward increasingly precise genetic modifications, Agrobacterium-mediated delivery is poised to remain a cornerstone technology for both basic research and crop improvement applications.

The Agrobacterium-mediated transformation stands as a cornerstone of plant biotechnology, enabling the transfer of genetic material into plant genomes. While binary vector systems have been the workhorse for decades, the emergence of ternary vector systems represents a significant evolutionary leap, particularly for delivering CRISPR-Cas reagents to recalcitrant plant species. This advancement is crucial for accelerating functional genomics and precision breeding in crops previously resistant to genetic transformation.

Traditional binary vectors consist of two plasmids: a T-DNA binary vector containing the genes of interest and a helper Ti plasmid carrying virulence (vir) genes. Ternary vector systems enhance this framework by incorporating a third, accessory plasmid that carries extra copies of key vir genes. This supplemental boost of virulence proteins has been shown to dramatically overcome the intrinsic biological barriers that limit transformation efficiency in many crop species [7] [21]. The fusion of this improved delivery system with CRISPR-Cas technology is now reshaping the landscape of plant genetic engineering.

The Technical Shift from Binary to Ternary Vector Systems

Core Architecture and Mechanism

The fundamental difference between binary and ternary systems lies in their plasmid composition and functional capacity:

- Binary Vector System: This conventional system uses two plasmids:

- T-DNA Binary Vector: Contains the genes of interest (e.g., Cas9 and gRNA expression cassettes) flanked by T-DNA borders.

- Helper Ti Plasmid: A disarmed plasmid that provides the essential vir genes required for T-DNA processing and transfer.

- Ternary Vector System: This enhanced system incorporates a third component:

The additive effect of these extra vir gene copies intensifies the plant's response to Agrobacterium infection. The enhanced virulence protein pool more effectively suppresses plant immune responses and facilitates higher efficiency T-DNA processing and delivery, effectively breaking down transformation barriers [7] [21].

Quantitative Evidence of Enhanced Performance

The superiority of ternary vector systems is demonstrated by substantial quantitative improvements in transformation efficiency across multiple plant species.

Table 1: documented Transformation Efficiency Enhancements Using Ternary Vector Systems

| Plant Species | Transformation Efficiency Increase (Fold) | Key Enabling Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maize | 3.9 to 6.8-fold | Ternary system united with morphogenic regulators (Bbm, Wus2) [23] | [23] |

| Maize inbred B104 | 4% to 6.4% (absolute frequency) | Ternary helper plasmid pKL2299, optimized media [22] | [22] |

| Sorghum, Soybean | 1.5 to 21.5-fold | Accessory vir genes and immune suppressors [7] [21] | [7] [21] |

| Wild tobacco (N. alata) | ~1% to >80% (absolute frequency) | Optimized hypocotyl transformation; CRISPR-Cas9 delivery [24] | [24] |

Beyond efficiency, ternary systems have proven highly effective for multiplex genome editing. In wild tobacco (Nicotiana alata), a ternary vector-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 system employing a polycistronic tRNA-gRNA (PTG) strategy successfully knocked out multiple allelic S-RNase genes simultaneously, achieving over 50% editing efficiency and creating self-compatible lines [24]. In wheat, an Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 system enabled the generation of mutants for four grain-regulatory genes with an average 10% edit rate in the T0 generation, allowing for the recovery of homozygous mutations [25].

Application Notes and Protocols

A Standardized Protocol for Maize Inbred B104 Transformation

The following optimized protocol, adapted from [22], details the use of a ternary vector system for efficient transformation and genome editing of the recalcitrant maize inbred B104. This method reduces the transformation timeline from over 160 days to just 60 days.

- Plant Material: Harvest B104 immature zygotic embryos (1.6–2.0 mm in length) 10–12 days after pollination. Ears can be stored at 4°C for 1–3 days before use.

- Agrobacterium Strain and Vectors:

- Strain: LBA4404.

- Ternary System: The strain should harbor both a conventional T-DNA binary vector (e.g., pKL2013, carrying Cas9, gRNA, and selectable marker) and a compatible ternary helper plasmid (e.g., pKL2299, containing additional vir genes from pTiBo542 with an RK2 origin) [22].

- Infection and Co-cultivation:

- Isolate embryos and infect with an Agrobacterium suspension (OD₆₀₀ = 0.4-0.8) for 15 minutes.

- Co-cultivate embryos on solid co-cultivation medium at 21°C in the dark for 3 days.

- Selection and Regeneration:

- Transfer embryos to callus induction medium containing a selective agent (e.g., bialaphos) and a bacteriostat (e.g., timentin). Culture for 2-3 weeks at 28°C in the dark.

- Move embryonic callus to regeneration medium, first to shoot induction medium for 2 weeks, then to root induction medium, under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod.

- Analysis of Transformed Plants:

- Extract genomic DNA from putative T0 plant leaves.

- Perform PCR and sequencing of the target genomic locus to identify CRISPR-Cas9-induced mutations.

This protocol, leveraging the ternary system, achieves an average transformation frequency of 6.4%, with over 66% of transgenic plants carrying targeted mutations [22].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural steps and component interactions in the ternary vector system transformation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of advanced Agrobacterium-mediated transformation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and genetic components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ternary Vector Systems

| Reagent / Component | Function / Purpose | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ternary Helper Plasmid | Provides supplemental vir genes to enhance T-DNA delivery efficiency and expand host range. | pKL2299 (for use with LBA4404) [22]; pVS1-based helpers [23] |

| Morphogenic Regulators (MRs) | Transcription factors that promote somatic embryogenesis and shoot regeneration in recalcitrant genotypes and species. | Baby boom (Bbm), Wuschel2 (Wus2); often used as inducible or excisable cassettes [23] [26] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Binary Vector | Carries the genome editing machinery within the T-DNA. | Vectors with plant-optimized Cas9 (e.g., driven by ZmUbi promoter) and gRNA(s) (e.g., driven by TaU6 promoter) [25] [22] |

| Engineered Agrobacterium Strains | Strains optimized for specific purposes, such as reduced environmental persistence or improved transformation in certain hosts. | Auxotrophic strains (e.g., thymidine auxotrophs); INTEGRATE-system engineered strains [1] |

| Chemical Inducers & Excision Systems | To control the temporal expression or remove transformation-enhancing genes (like MRs) after regeneration to ensure normal plant development. | Estradiol-inducible systems (e.g., for BrrWUSa) [26]; Cre/loxP site-specific recombination [23] |

The transition from binary to ternary vector systems marks a pivotal advancement in Agrobacterium-mediated delivery, effectively overcoming one of the most significant bottlenecks in plant biotechnology. By integrating accessory virulence plasmids, these systems achieve unprecedented transformation efficiencies in previously recalcitrant crops. When combined with morphogenic regulators and modern genome editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9, ternary vectors provide a robust and versatile platform for functional genomics and precision breeding. This powerful synergy between delivery and editing technologies is poised to drive the development of more resilient and high-performing crops, essential for addressing global agricultural challenges.

The successful Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of CRISPR reagents is a cornerstone of modern plant genetic engineering. This process hinges on three interdependent pillars: the host range of the bacterial vector, the careful selection of explants, and the efficiency of tissue culture regeneration systems. Overcoming challenges in these areas is critical for applying CRISPR-Cas technology to a broader spectrum of plant species, particularly those deemed recalcitrant to genetic transformation. This protocol outlines key considerations and methodologies to optimize these factors, providing a framework for researchers to advance functional genomics and precision crop breeding.

Host Range and Agrobacterium Strain Selection

The inherent host range specificity of Agrobacterium tumefaciens can be a significant barrier to transforming non-model plant species. Recent advancements in vector engineering are directly addressing this limitation.

Ternary Vector Systems

Ternary vector systems represent a transformative innovation that enhances the virulence of Agrobacterium, thereby expanding its effective host range. Unlike traditional binary vectors, these systems incorporate accessory virulence genes and immune suppressors that help overcome the intrinsic transformation barriers of recalcitrant crops [7]. Their application has enabled remarkable 1.5- to 21.5-fold increases in stable transformation efficiency in species previously resistant to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, such as maize, sorghum, and soybean [7].

Agrobacterium Strain Engineering

Precise genome engineering of Agrobacterium itself is now possible, allowing for the development of specialized strains. The INTEGRATE system—a CRISPR RNA-guided transposase—enables high-fidelity, marker-free genomic modifications in Agrobacterium [1]. This technology can be used to create auxotrophic strains (e.g., through thymidylate synthase knockout), which require specific nutritional supplements. These strains offer improved biosafety by reducing environmental persistence and can enhance transformation efficiency by minimizing bacterial overgrowth during co-cultivation with plant tissues [1].

Quantitative Comparison of Transformation Technologies

Table 1: Key Transformation Technologies and Their Efficiencies

| Technology | Key Feature | Best For | Reported Efficiency Gains | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ternary Vector Systems | Delivers accessory virulence genes | Recalcitrant crops (maize, sorghum, soybean) | 1.5 to 21.5-fold increase in stable transformation [7] | Requires vector construction |

| Biolistics with FGB | Flow Guiding Barrel optimizes particle flow | Species resistant to Agrobacterium; DNA-free RNP delivery | 4.5-fold increase in RNP editing; 10-fold higher stable transformation in maize [20] | Can cause tissue damage; complex transgene insertions |

| Protoplast Transfection | PEG-mediated DNA-free editing | Species with established protoplast regeneration | Up to 64% regeneration frequency; 40% transfection efficiency [27] | Requires high-efficiency protoplast regeneration system |

| INTEGRATE-mediated Agrobacterium Engineering | Creates auxotrophic and disarmed strains | Improving biosafety and reducing contamination | High-efficiency, marker-free genome modifications in Agrobacterium [1] | Specialized technical expertise required |

Explant Selection and Preparation

The choice of explant is a critical determinant of transformation success, as it must possess high regenerative capacity and be accessible to Agrobacterium infection.

Meristematic and Nodal Explants

Explants rich in meristematic tissues are often preferred due to their active cell division and high totipotency. Nodal culture is particularly powerful for recalcitrant horticultural crops, utilizing sterilized immature nodal explants (1–2 cm in length) containing abundant intercalary and apical meristematic cells [28]. These cells exhibit high mitotic activity and enhanced totipotency, and they retain less water compared to other explants, making them more conducive to regeneration [28]. This method has been successfully applied to species including Garcinia mangostana, Artocarpus heterophyllus, Cucumis melo, and Citrus limon [28].

Explant Sterilization Protocol

Proper sterilization is essential to prevent microbial contamination without compromising explant viability.

- Cleaning: Clean immature nodal explants with a liquid detergent (Tween 20) and rinse thoroughly with distilled water for 20 minutes [28].

- Antimicrobial Treatment: Immerse explants in a fungicide-bactericide solution containing carbendazim (0.1%) and streptocycline (0.1%) for 20 minutes, then wash 4–5 times with distilled water [28].

- Surface Sterilization: Immerse in 70% ethanol for 5 minutes, followed by treatment with 0.8–1.0% sodium hypochlorite for 20 minutes [28].

- Rinsing: Rinse 3–5 times with sterile distilled water to remove all residual sterilants [28].

Media Formulation for Explant Establishment

Sterilized explants are inoculated onto media such as Murashige and Skoog (MS) or Driver-Kuniyuki (DKW), supplemented with plant growth regulators. A typical formulation includes 0.01–2 mg/L auxin and 0.4–4 mg/L cytokinin, or a combination of both [28]. Cultures are maintained under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod at 25 ± 2°C, with shoot regeneration typically occurring within 4–8 weeks [28].

Tissue Culture Regeneration Systems

Efficient regeneration of whole plants from transformed cells is often the bottleneck in plant genetic engineering. The following systems have proven effective across diverse species.

Clustered Bud System for Woody Plants

For challenging woody species like Fraxinus mandshurica, a clustered bud system has been developed to induce and screen homozygous edited plants [4]. This system involves supplementing media with hormones at different concentrations to promote the formation of multiple buds from a single transformed growing point. Among 100 randomly transformed growing points, 18% of the induced clustered buds were confirmed to be gene-edited, demonstrating the system's effectiveness for both regeneration and screening [4].

Protoplast Regeneration System

For species like Brassica carinata, a highly efficient, five-stage protoplast regeneration protocol has been developed [27]. The key to success lies in adjusting media composition and plant growth regulators at different developmental stages:

- Stage I (Cell Wall Formation): Requires high concentrations of NAA and 2,4-D in the initial medium (MI) [27].

- Stage II (Active Cell Division): Requires a lower auxin concentration relative to cytokinin (MII) [27].

- Stage III (Callus Growth & Shoot Induction): Essential high cytokinin-to-auxin ratio (MIII) [27].

- Stage IV (Shoot Regeneration): Optimal with even higher cytokinin-to-auxin ratio (MIV) [27].

- Stage V (Shoot Elongation): Requires only low levels of BAP and GA3 (MV) [27].

This optimized protocol achieves an average regeneration frequency of up to 64% and a transfection efficiency of 40% using the GFP marker gene [27].

In Planta Genome Editing System (IPGEC)

To bypass tissue culture entirely, an in planta genome editing system has been developed for species like citrus [29]. This system co-delivers Cas9, multiple sgRNAs, regeneration-promoting transcription factors (e.g., WUS, STM, IPT), and T-DNA delivery enhancers via Agrobacterium to soil-grown seedlings. This approach enables transgene-free, biallelic editing without tissue culture, significantly accelerating trait improvement while avoiding somaclonal variation [29].

Quantitative Data on Regeneration Efficiencies

Table 2: Regeneration Efficiencies Across Different Plant Systems

| Plant Species | Explant Type | Regeneration System | Key Growth Regulators | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraxinus mandshurica | Growing points | Clustered bud system | Hormones at varying concentrations (specifics not detailed) | 18% gene-edited clustered buds [4] |

| Brassica carinata | Leaf protoplasts | Five-stage protoplast regeneration | Stage-specific NAA, 2,4-D, cytokinins, BAP, GA3 | 64% regeneration frequency; 40% transfection efficiency [27] |

| Recalcitrant horticultural crops | Immature nodal segments | Nodal culture | 0.01-2 mg/L auxin; 0.4-4 mg/L cytokinin | Shoot regeneration in 4-8 weeks [28] |

| Citrus | Soil-grown seedlings | In Planta Genome Editing (IPGEC) | WUS, STM, IPT transcription factors | High-efficiency editing in commercial cultivars [29] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery and Plant Regeneration

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | EHA105, K599, C58C1 [4] [29] | Engineered for plant transformation; strain selection affects host range and efficiency. |

| CRISPR Delivery Vectors | pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N [4], Ternary vectors [7] | Carry Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA expression cassettes for plant transformation. |

| Plant Growth Regulators | Auxins (NAA, 2,4-D), Cytokinins (BAP) [27] [28] | Direct cell fate in tissue culture; critical ratios induce callus, shoot, or root formation. |

| Culture Media | MS, DKW, WPM [4] [28] | Provide essential nutrients and minerals; selection depends on plant species and explant type. |

| Selection Agents | Kanamycin [4] | Select for transformed tissues when combined with appropriate resistance genes in T-DNA. |

| Sterilization Agents | Ethanol, Sodium Hypochlorite, Tween 20 [28] | Surface sterilize explants to prevent microbial contamination in tissue culture. |

Regulatory Pathways in Explant Regeneration

The regeneration capacity of explants is governed by complex molecular pathways. Understanding these networks can inform protocol optimization, particularly through the strategic use of plant growth regulators.

Integrated Experimental Workflow

A successful transformation project integrates considerations of host range, explant selection, and regeneration into a cohesive workflow. The following diagram outlines this integrated process from explant preparation to plant acclimatization.

Concluding Remarks

The successful integration of Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR delivery with robust regeneration systems requires careful optimization of all three components covered in this protocol. The expansion of host range through ternary vector systems and engineered Agrobacterium strains, combined with the strategic use of meristematic explants and stage-specific regeneration protocols, is breaking down barriers in plant genetic engineering. By applying these principles and protocols, researchers can accelerate the development of improved crop varieties with enhanced precision and efficiency.

Advanced Workflows and Crop-Specific Protocols

Within the broader scope of CRISPR reagent delivery research, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation stands as a cornerstone method for plant genome engineering. [30] [16] This technique leverages the natural DNA transfer capability of Agrobacterium tumefaciens to deliver CRISPR/Cas components into plant cells, enabling precise genomic modifications. [31] The method is particularly valued for its ability to generate stable transformants and for its relatively high efficiency in a wide range of plant species, though its success is often genotype-dependent. [16] [31] This protocol outlines a standardized pipeline, integrating key optimizations from recent studies to ensure robust delivery of CRISPR reagents for effective genome editing in plants.

Principle of the Method

The type II CRISPR/Cas9 system from Streptococcus pyogenes functions as a highly programmable genome editing tool. [32] [11] Its core components are two elements: the Cas9 endonuclease and a single guide RNA (sgRNA). [32] [11] The sgRNA directs the Cas9 protein to a specific genomic locus through complementary base pairing. Upon recognition of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), typically 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9, the nuclease induces a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA. [11]

The cellular repair of this DSB is harnessed for genome editing. The predominant Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway often results in small insertions or deletions (indels), leading to gene knockouts. [32] [11] The less frequent Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway can be co-opted for precise gene insertion or replacement when a donor repair template is provided. [32] [16]

Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediates the delivery of the genes encoding these CRISPR components via its Transfer DNA (T-DNA). [31] The T-DNA, defined by left and right border sequences, is integrated into the plant genome, leading to the stable expression of Cas9 and sgRNA(s). This results in heritable genomic edits. [30] [16]

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental pipeline, from vector construction to the analysis of edited plants:

Key Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of this pipeline depends on critical reagents and genetic components. The table below details the essential "Research Reagent Solutions" required for establishing an efficient Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR delivery system.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery

| Reagent / Component | Function & Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector System | Carries T-DNA with CRISPR expression cassettes; backbone allows replication in both E. coli and Agrobacterium. | Ternary systems [30] or all-in-one vectors (e.g., pX260, pX330 [32]) with plant codon-optimized Cas9. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Engineered endonuclease that creates DSBs at target sites specified by the sgRNA. | SpCas9 is most common; high-fidelity variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1 [11]) reduce off-target effects. |

| Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Chimeric RNA that combines crRNA and tracrRNA functions for target recognition and Cas9 binding. | Driven by Pol III promoters (e.g., U6, U3 [25]); target sequence uniqueness is critical. |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Engineered soil bacterium that naturally transfers T-DNA into plant genomes. | Common strains: EHA105, LBA4404, GV3101; disarmed versions lack phytohormone genes for normal regeneration. [4] [31] |

| Plant Explants & Media | Source of plant cells/tissues for transformation and specialized media for regeneration. | Hypocotyls, immature embryos, leaf discs; media contain auxins/cytokinins for organogenesis. [24] |

| Selection Agents | Allows growth of transformed cells by conferring resistance to antibiotics or herbicides. | Kanamycin, hygromycin; resistance gene (e.g., NptII, HptII) included in T-DNA. [16] |

Equipment and Software

Laboratory Equipment

- Thermocycler: For PCR amplification during vector construction and genotyping.

- Electroporator or Water Bath: For introducing the plasmid vector into Agrobacterium cells.

- Laminar Flow Hood: Provides a sterile environment for all plant tissue culture work.

- Plant Growth Chambers or Incubators: For maintaining controlled conditions (temperature, light, humidity) for co-cultivation and plant regeneration.

- Centrifuges: For pelleting bacterial cultures and processing plant samples.

- Gel Electrophoresis System: For analyzing PCR products and checking DNA constructs.

- Sequencing Facility Access: For confirming plasmid sequences and genotyping edited plants.

Software and Bioinformatics Tools

- gRNA Design Software (e.g., CRISPR-P, CHOPCHOP): For selecting specific sgRNA targets with minimal off-site effects. [11]

- Sequence Analysis Tools (e.g., BLAST, Clustal Omega): For verifying target sequence uniqueness and designing primers.

- Plasmid Design Software: For planning and visualizing genetic constructs.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Stage 1: Vector Construction andAgrobacteriumPreparation

Step 1: Design and Clone sgRNA Expression Cassette(s)

- Design sgRNAs: Use bioinformatics software to select 20-nt target sequences specific to your gene of interest, located immediately 5' to a PAM (NGG for SpCas9). [11] Check for potential off-target sites across the genome.

- Clone into Binary Vector: Insert the annealed oligonucleotides encoding the sgRNA into the sgRNA expression site of a binary vector (e.g., pTagRNA4, pLC41-based vectors) using Golden Gate cloning (e.g., with BsaI) or traditional restriction-ligation. [25] For multiplex editing, use a polycistronic tRNA-gRNA (PTG) strategy or a vector with multiple sgRNA expression sites. [24] [11]

- Transform Agrobacterium: Introduce the verified binary vector into a suitable Agrobacterium strain (e.g., EHA105) via electroporation or freeze-thaw transformation. [4] Select transformed colonies on appropriate antibiotics.

Step 2: PrepareAgrobacteriumCulture for Transformation

- Inoculate and Grow: Pick a single positive colony and inoculate a liquid culture (e.g., YEP or LB medium with appropriate antibiotics). Grow at 28°C with shaking (200-250 rpm) for ~24 hours until the late log phase. [4]

- Induce and Adjust Culture: Centrifuge the culture and resuspend the bacterial pellet in an induction medium (e.g., containing acetosyringone, typically 100-200 µM) to mimic plant wound signals. Adjust the final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) to the optimal value for your plant species. The table below provides optimized parameters from recent studies.

Table 2: Optimized Agrobacterium Infection Parameters for Different Plant Systems

| Plant Species / System | Optimal OD₆₀₀ | Optimal Infection Duration | Key Explant Type | Reported Editing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (Fielder) | Information Missing | Information Missing | Immature embryos | Average 10% (up to 68 mutants recovered for 4 genes) [25] |

| Wild Tobacco (N. alata) | Information Missing | Information Missing | Hypocotyls | >50% (PDS gene) [24] |

| Manchurian Ash (F. mandshurica) | 0.5 - 0.8 | Information Missing | Embryonic growing points | 18% of induced clustered buds [4] |

Stage 2: Plant Transformation and Regeneration

Step 3: Infect Plant Explants

- Prepare Explants: Surface-sterilize seeds or tissues and isolate the target explants (e.g., hypocotyls, immature embryos, leaf discs). A hypocotyl-based system boosted transformation efficiency in wild tobacco from ~1% to over 80%. [24]

- Inoculate: Immerse the explants in the prepared Agrobacterium suspension for the optimal duration (often 15-30 minutes), with gentle agitation.

Step 4: Co-cultivation

- Transfer Explants: Blot the explants dry on sterile filter paper and place them on solid co-cultivation medium (containing acetosyringone but no antibiotics).

- Incubate: Incubate the plates in the dark at a plant-specific temperature (e.g., 22-25°C) for 2-3 days. This allows Agrobacterium to attach to plant cells and transfer the T-DNA.

Step 5: Resting, Selection, and Regeneration

- Resting Phase: Transfer explants to a resting medium containing antibiotics (e.g., timentin or cefotaxime) to kill the Agrobacterium but without the plant selection agent. This reduces bacterial overgrowth and allows plant cell recovery.

- Selection Phase: Move explants to a selection medium containing both antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium and a selective agent (e.g., kanamycin) to inhibit the growth of non-transformed plant cells. Subculture to fresh selection media every 2-3 weeks.

- Regeneration: As resistant calli form, transfer them to regeneration media, often with adjusted phytohormone ratios to promote shoot formation. Subsequently, transfer developed shoots to rooting medium. [24] [31] The molecular process of T-DNA transfer and editing is shown below:

Stage 3: Molecular Analysis and Validation

Step 6: Screen Regenerated Plants (T0)

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest leaf tissue from regenerated plants and extract genomic DNA.

- PCR and Sequencing: Amplify the target genomic region by PCR and sequence the products (via Sanger or NGS) to detect mutations. Screening a small population of transgenic wheat plants (T0, T1, T2) allowed recovery of homozygous mutants without detecting off-target mutations in the most active lines. [25]

- Calculate Editing Efficiency: Determine the percentage of independently regenerated plants that carry mutations at the target locus.

Step 7: Assess Off-Target Effects

- In Silico Prediction: Use software to predict potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity to the sgRNA.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the top potential off-target sites from genomic DNA and sequence them to check for unintended edits. [25]

Troubleshooting

Table 3: Common Issues and Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Transformation Efficiency | Non-optimal Agrobacterium vitality or density. | Ensure bacteria are in log growth phase; optimize OD600 and infection time. [4] |

| No Regenerants After Selection | Selection pressure too high; explant not competent for regeneration. | Titrate selection agent concentration; use highly regenerable explant types and optimized hormone media. [24] |

| No Mutations Detected (Transformation Successful) | Low CRISPR/Cas9 activity; poor sgRNA design. | Verify sgRNA sequence and Cas9 codon-optimization for the plant species; use validated promoters (e.g., ZmUbi for Cas9, TaU6 for sgRNA in wheat). [25] |

| High Chimerism in T0 Plants | Editing occurred after initial cell division. | Regenerate from single cells (e.g., via protoplasts) or advance to T1 generation to segregate mutations. [16] |

| High Off-Target Effects | sgRNA has multiple near-identical matches in the genome. | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1); design sgRNAs with maximal on-target and minimal off-target scores. [11] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Editing Efficiency: Calculate as (number of edited T0 plants / total number of T0 plants analyzed) * 100%. Efficiencies can vary significantly; for example, reports include >50% in N. alata and 10% in wheat. [25] [24]

- Mutation Characterization: Classify the types and frequencies of induced mutations (e.g., deletions, insertions). In wheat, large deletions (>10 bp) were reported as the dominant mutation type. [25]

- Homozygous Mutant Recovery: Identify plants with bi-allelic mutations in the T0 generation or screen the T1 progeny of heterozygous T0 plants to find homozygous individuals. In wheat, homozygous mutants with a 1160-bp deletion in TaCKX2-D1 showed a significant increase in grain number per spikelet多元化. [25]

This standardized protocol for Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of CRISPR/Cas reagents provides a reliable pathway for achieving heritable genome edits in plants. The integration of optimized ternary vector systems [30], species-specific promoters [25], and improved regeneration techniques [24] has significantly enhanced the efficiency and scope of this method. This pipeline is instrumental for both basic research, such as functional gene characterization in wild relatives like Nicotiana alata [24] and Fraxinus mandshurica [4], and for applied crop improvement, enabling the development of novel traits in species like oil palm [31] and wheat [25]. As the field progresses, further refinements in vector design, Agrobacterium strains, and tissue culture methods will continue to expand the utility of this powerful genome editing delivery platform.

Within the broader scope of a thesis on Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of CRISPR reagents, the design and assembly of the transformation construct represent a critical foundational step. The choice of regulatory elements, particularly promoters, and the strategy for vector assembly directly determine the efficiency of reagent delivery, the frequency of mutagenesis, and the successful recovery of edited plants. This protocol details evidence-based strategies for selecting promoters and assembling binary vectors for CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing in plants, with a focus on applications in both model and recalcitrant species. The guidelines are framed to help researchers overcome specific bottlenecks in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, such as low editing efficiency and genotype dependency.

Promoter Selection for CRISPR/Cas9 Expression Cassettes

The promoter drives the consistent and robust expression of the Cas nuclease and the guide RNA (gRNA). Selection is based on the desired expression pattern (constitutive, tissue-specific, or transient) and the host organism's compatibility.

Table 1: Promoter Selection for Cas9 and gRNA Expression

| Component | Promoter Type | Example Promoters | Key Characteristics | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | Constitutive | CaMV 35S, OsUbiquitin (OsUbi), ZmUbiquitin (ZmUbi), Endogenous Constitutive (e.g., FmECP3) | Drives strong, continuous expression in most tissues; 35S is broad-range, ubiquitin promoters often stronger in monocots [33] [34]. Endogenous promoters can show superior activity (e.g., 5.48x higher than control) [35]. | Standard workhorse for stable transformation; species-specific promoters can significantly boost efficiency in recalcitrant species [35]. |

| gRNA | RNA Polymerase III | AtU6, OsU6, Truncated Endogenous Variants (e.g., FmU6-6-4) | Precise transcription initiation and termination; critical for gRNA accuracy. Species-specific U6 variants can drive sgRNA expression >3x higher than heterologous promoters [35]. | Default choice for gRNA expression; cloning the native U6 promoter from the target species is highly recommended to maximize editing efficiency [35]. |

Vector Assembly and Engineering

The assembly of the binary vector involves cloning the chosen expression cassettes for Cas9 and sgRNA(s) into a T-DNA region, which is then transferred into the plant genome by Agrobacterium.

Basic Workflow for Vector Construction

The following workflow outlines the key steps for constructing a CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector.

Advanced Vector Engineering Strategies

Recent research has highlighted several strategies to enhance vector performance:

- Binary Vector Copy Number Engineering: Introducing point mutations into the plasmid's origin of replication (ori) can increase its copy number within Agrobacterium. This simple engineering step has been shown to improve plant transformation efficiency by up to 100% and fungal transformation by up to 400%, as higher copy numbers lead to more T-DNA copies available for delivery [36].

- Multiplexing with tRNA Processing Systems: For multi-gene editing, multiple gRNA expression units can be assembled in a single vector using a tRNA-processing system. The gRNA sequences are flanked by tRNA, which are cleaved post-transcriptionally to release individual gRNAs. This strategy was successfully used to create an optimized vector for pea,

PsU6.3-tRNA-PsPDS3-en35S-PsCas9[37]. - Self-Removing CRISPR Vectors: To generate transgene-free edited plants, the Cas9 and SMG expression cassettes can be flanked by target sites for gRNAs expressed from the same T-DNA. After editing, the CRISPR machinery excises itself, allowing for the recovery of edited plants without the transgene in the next generation [38].

Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Construct Design and Assembly

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vector | Carries T-DNA for transfer into plant genome. | pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N [4], pZNH2GTRU6 [34]. Backbone sequence and ori impact efficiency [36]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target DNA site. | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) is most common. Newer variants (e.g., SpRY) relax PAM constraints [33]. |

| Restriction Enzymes / Cloning Kit | Assembly of expression cassettes into the vector. | BsaI, BbsI for Golden Gate assembly [33] [34]. In-Fusion HD cloning kits also widely used [34]. |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Mediates delivery of T-DNA into plant cells. | EHA105 [4] [34], LBA4404 [38]. Strain choice can affect host range and efficiency. |

| Web-Based gRNA Design Tools | In silico selection of specific gRNA targets and off-target prediction. | CRISPR-P 2.0, CHOPCHOP, Cas-Designer [33]. Species-specific tools like WheatCRISPR improve accuracy for complex genomes [33]. |

| Developmental Regulators (DRs) | Co-expressed to enhance transformation & regeneration. | WUS2, BBM boost embryogenesis; GRF4-GIF1 fusion enhances shoot regeneration in recalcitrant varieties [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Protocol 1: Construction of a CRISPR/Cas9 Binary Vector

This protocol adapts established methods for assembling a binary vector containing a Cas9 expression cassette and one or more gRNA expression cassettes [33] [4].

Materials:

- Purified plasmid DNA of your chosen binary vector (e.g., pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N).

- Cas9 expression cassette (e.g., with 35S or Ubiquitin promoter).

- DNA fragment for the gRNA scaffold under a U6 promoter.

- Oligonucleotides for your target-specific gRNA sequence.

- Appropriate restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI) and ligase.

- Competent E. coli cells.

Procedure:

- sgRNA Oligo Annealing:

- Design forward and reverse oligonucleotides (∼20-nt target sequence) with 5' overhangs compatible with your digested vector.

- Resuspend oligonucleotides to 100 µM in annealing buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5–8.0).

- Mix equal volumes, heat to 95°C for 5 minutes, and cool slowly to room temperature (∼1–2 hours). Dilute the annealed duplex 1:100 before use.

Vector Digestion:

- Digest 1–2 µg of the binary vector with the appropriate restriction enzyme (e.g., BsaI for a Golden Gate assembly) in a 20 µL reaction for 1–2 hours at the recommended temperature.

Ligation:

- Set up a ligation reaction containing the digested vector and the diluted, annealed oligo duplex. Use a vector:insert molar ratio of ∼1:10. Incubate with T4 DNA ligase at room temperature for 1 hour or 16°C overnight.

Transformation and Screening:

- Transform the ligation product into competent E. coli cells.

- Select transformed colonies on antibiotic-containing plates.

- Screen colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest to confirm the correct insertion of the gRNA sequence.

Sequencing and Agrobacterium Transformation:

- Sequence the final plasmid from a positive E. coli colony to verify the entire sequence of the inserted gRNA and the absence of mutations.

- Transform the validated plasmid into your chosen Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., EHA105) using the freeze-thaw method [38].

Protocol 2: Validating gRNA Efficiency with an In Vitro Cleavage Assay

Before proceeding with plant transformation, validating the functionality of the designed gRNAs is highly recommended [39].

Materials:

- Purified CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid or synthetic gRNA and commercial Cas9 protein.

- Plant genomic DNA from the target cultivar.

- PCR reagents and primers flanking the target site (producing an amplicon of 500–800 bp).

- Gel electrophoresis equipment.

Procedure:

- Amplify Target Locus: Perform PCR using the cultivar's genomic DNA to amplify a fragment containing the gRNA target site.

- Set Up Cleavage Reaction:

- If using a plasmid: Incubate the PCR amplicon (∼200 ng) with the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid (∼200 ng) in a nuclease buffer.

- If using RNP complex: Pre-complex purified Cas9 protein (e.g., 100–200 ng) with synthetic gRNA (molar ratio 1:2) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Then add the PCR amplicon.

- Incubate and Analyze: Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 1 hour. Run the products on a 1.5–2% agarose gel. A successful cleavage will result in the full-length amplicon being cut into two smaller, distinct bands.

- Quantify Efficiency: Use gel image analysis software to estimate the cleavage efficiency as the intensity ratio of the cut bands to the total DNA (cut + uncut). Proceed with plant transformation for gRNAs showing efficient cleavage in vitro.

The strategic selection of promoters and careful assembly of the binary vector are non-negotiable prerequisites for successful Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR genome editing. As research advances, the trend is moving toward using species-specific endogenous promoters and engineered vector backbones to push the boundaries of efficiency, especially in recalcitrant species. By adhering to the detailed protocols and utilizing the recommended reagent toolkit outlined in this document, researchers can construct robust and highly efficient CRISPR systems. This establishes a solid foundation for subsequent Agrobacterium-mediated delivery and the regeneration of genome-edited plants, directly contributing to the overarching goals of functional genomics and precision crop breeding.

The application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology in wheat improvement has been historically challenged by the predominant use of biolistic transformation methods, which often result in complex integration patterns and transgene silencing [25]. This case study details the development of an optimized Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR system for hexaploid wheat, addressing key limitations in transformation efficiency and editing specificity. The system leverages advanced vector design and optimized tissue culture protocols to achieve high-efficiency genome editing in elite wheat cultivars, providing researchers with a robust tool for functional genomics and trait improvement [40] [25].

Within the broader context of Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of CRISPR reagents, this research demonstrates how tailored approaches can overcome species-specific barriers. The polyploid nature of the wheat genome (2n = 6x = 42) presents unique challenges for genome editing, including higher potential for off-target effects and the necessity for simultaneous editing of multiple homoeologous alleles [41] [42]. The protocol described herein successfully addresses these challenges through careful selection of regulatory elements and optimization of delivery parameters.

Results and Discussion

System Development and Optimization

The development of an efficient Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR system required optimization across multiple parameters, including vector design, selection of regulatory elements, and tissue culture conditions. A critical innovation was the incorporation of the JD633-GRF4-GIF1 vector system, which substantially reduces regeneration time to under 90 days while enabling efficient transformation of elite wheat cultivars [40]. This represents a significant improvement over conventional protocols that often require extended regeneration periods and are genotype-dependent.

Comparison of delivery methods revealed distinct advantages of the Agrobacterium-based approach over biolistic transformation. The Agrobacterium system consistently produced lower-copy-number integrations and reduced transgene silencing, facilitating more stable inheritance of edits across generations [25]. Additionally, the continued activity of CRISPR-Cas9 through generations enabled recovery of novel mutations in T1 and T2 populations, reducing the number of primary transformants required for successful editing [25].

Editing Efficiency and Specificity

The optimized system demonstrated an average edit rate of 10% across four grain-regulatory genes (TaCKX2-1, TaGLW7, TaGW2, and TaGW8) in T0, T1, and T2 generation plants [25]. Notably, different mutation patterns were observed in wheat compared to other plant species, with deletions exceeding 10 bp constituting the dominant mutation type [25]. The system successfully generated homozygous mutants in a single generation, including a 1160-bp deletion in TaCKX2-D1 that significantly increased grain number per spikelet [25].

Comprehensive analysis confirmed the absence of off-target mutations in the most Cas9-active plants, validating the specificity of the designed gRNAs [25]. This high specificity is particularly notable given wheat's complex genome, which contains over 80% repetitive sequences that pose significant challenges for precise targeting [41] [42].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPR Delivery Methods in Wheat

| Parameter | Agrobacterium-Delivered System | Biolistic Transformation |

|---|---|---|