Base Editors in Genome Engineering: A Comprehensive Guide to Precision Tools for Research and Therapy

Base editors represent a revolutionary class of CRISPR-derived genome engineering tools that enable the direct, programmable conversion of a single DNA base into another without creating double-stranded DNA breaks.

Base Editors in Genome Engineering: A Comprehensive Guide to Precision Tools for Research and Therapy

Abstract

Base editors represent a revolutionary class of CRISPR-derived genome engineering tools that enable the direct, programmable conversion of a single DNA base into another without creating double-stranded DNA breaks. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational mechanisms of Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) and Adenine Base Editors (ABEs), their diverse methodological applications in research and therapy, persistent challenges like off-target effects and bystander editing, and the critical frameworks for validating editing efficiency and specificity. By synthesizing current advancements and comparative analyses, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to strategically implement base editing technologies to address genetic diseases and accelerate therapeutic development.

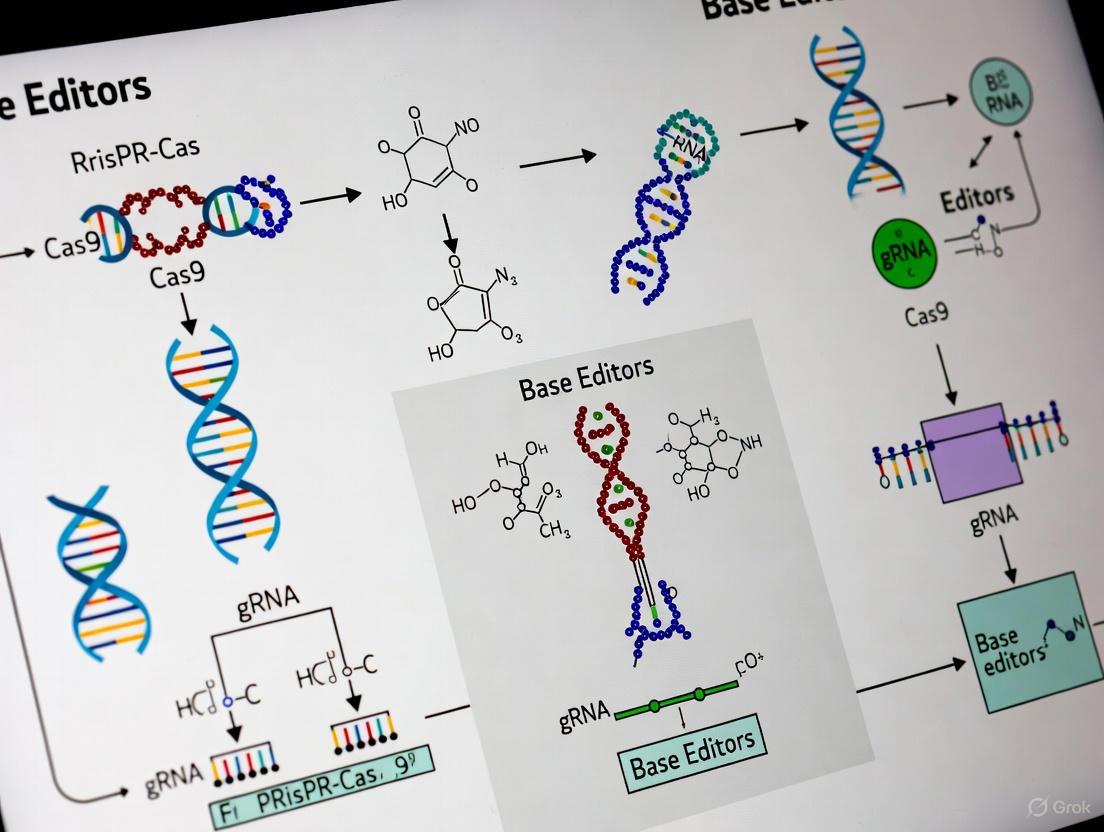

The Foundation of Precision: Understanding Base Editor Mechanisms and Components

Base editing represents a transformative advancement in genome engineering, enabling precise, single-nucleotide alterations without inducing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs). This technology leverages fusion proteins combining catalytically impaired CRISPR-Cas systems with nucleobase deaminases, directly converting one base pair to another through chemical modification. Unlike conventional nuclease-based CRISPR approaches that rely on cellular repair mechanisms following DSBs, base editing operates through fundamentally different biochemical principles, offering higher efficiency and purity in installing point mutations. This technical guide examines the molecular architecture, mechanisms, and experimental applications of base editing technologies, framing them within the broader paradigm shift toward precision genetic engineering in research and therapeutic development.

Traditional CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized biological research by enabling targeted genomic modifications through RNA-programmed DNA cleavage. However, its dependence on double-strand break generation and subsequent cellular repair pathways introduces significant limitations, including unpredictable indel formation, chromosomal rearrangements, and low efficiency of precise point mutation installation, particularly in non-dividing cells [1] [2].

Base editing emerged in 2016 as a groundbreaking alternative that addresses these limitations by directly rewriting one DNA base into another without DSB formation [3]. This technology has expanded the genome editing toolkit beyond cutting and patching to include precise chemical conversion, establishing a new paradigm for therapeutic correction of point mutations—which constitute the largest class of known human genetic variants associated with disease [4] [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Editing Technologies

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Base Editing | Prime Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Double-strand break induction | Direct chemical base conversion | Reverse transcription of new sequence |

| DSB Formation | Required | Avoided | Avoided |

| Donor Template | Required for HDR | Not required | Encoded in pegRNA |

| Primary Editing Outcomes | Indels (NHEJ) or targeted integration (HDR) | C•G to T•A or A•T to G•C transitions | All 12 possible base-to-base conversions, small insertions/deletions |

| Editing Efficiency in Non-dividing Cells | Low (HDR inefficient) | High | Moderate to high |

| Therapeutic Application | Gene disruption | Point mutation correction | Point mutation correction, small insertions/deletions |

| Key Limitations | Off-target indels, complex rearrangements | Restricted to specific transition mutations, bystander edits | Lower efficiency, larger construct size |

Molecular Architecture of Base Editors

Base editors are sophisticated fusion proteins that combine multiple enzymatic functions to achieve precise nucleotide conversion. Their core components work in concert to target specific genomic loci and execute chemical modifications on DNA bases.

Core Protein Components

The foundational architecture of base editors consists of three essential elements:

Catalytically Impaired Cas Protein: Either Cas9 nickase (nCas9) with a single active nuclease domain or completely deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) serves as a programmable DNA-binding module that localizes the editor to specific genomic sites without generating DSBs [6] [7]. The nickase variant (containing a D10A mutation in SpCas9) creates a single-strand break in the non-edited DNA strand, enhancing editing efficiency by directing cellular repair to utilize the edited strand as a template [4].

Nucleobase Deaminase: This enzyme performs the central chemical conversion of target nucleotides. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) utilize cytidine deaminases (e.g., APOBEC1) that convert cytosine to uracil, while adenine base editors (ABEs) employ engineered adenosine deaminases (e.g., TadA*) that convert adenine to inosine [8] [4].

Accessory Proteins: In CBEs, uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) is fused to prevent excision of the uracil intermediate by cellular base excision repair (BER) pathways, thereby increasing editing efficiency and product purity [4] [1].

Guide RNA and Targeting Constraints

Base editors employ standard CRISPR guide RNAs (gRNAs) for DNA targeting, but with unique design considerations. The target base must be strategically positioned within a specific "editing window" relative to the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence [6]. This window typically spans nucleotides 4-8 (counting the PAM as positions 21-23) in SpCas9-derived editors, creating a constraint that must be addressed during gRNA design [4].

Diagram 1: Base editor targeting requires precise positioning of the editing window relative to the PAM sequence.

Mechanisms of Base Editing

The molecular mechanism of base editing involves a coordinated sequence of DNA binding, chemical modification, and cellular processing that ultimately results in permanent nucleotide conversion.

Cytosine Base Editing (CBE) Pathway

Cytosine base editors initiate a multi-step process that converts C•G base pairs to T•A pairs:

DNA Binding and Strand Separation: The gRNA directs the CBE to the target genomic locus, where nCas9 binds and unwinds the DNA duplex, forming an R-loop structure that exposes a single-stranded DNA region [4] [6].

Cytosine Deamination: The APOBEC1 deaminase domain catalyzes the hydrolytic deamination of cytosine bases within the editing window, converting them to uracils by removing an amino group [3] [4].

Cellular Processing: The resulting U•G mismatch undergoes cellular repair processes. UGI inhibits uracil N-glycosylase, preventing erroneous uracil excision. Nicking of the non-edited strand by nCas9 directs the mismatch repair (MMR) system to preferentially replace the G with an A, using the uracil-containing strand as a template [4].

DNA Replication Outcome: During subsequent DNA replication, the uracil is read as thymine, resulting in a permanent C•G to T•A base pair conversion [6].

Diagram 2: The CBE mechanism involves DNA binding, cytosine deamination, cellular processing, and permanent conversion.

Adenine Base Editing (ABE) Pathway

Adenine base editors operate through a conceptually similar but chemically distinct pathway:

DNA Binding and Strand Separation: Similar to CBEs, ABEs use nCas9 to bind DNA and expose a single-stranded region through R-loop formation [4] [1].

Adenine Deamination: The engineered TadA deaminase domain converts adenine to inosine through deamination. Unlike cytosine deaminases, natural adenine deaminases acting on DNA did not exist and were engineered through extensive protein evolution [4] [2].

Cellular Interpretation: The DNA replication machinery interprets inosine as guanosine, leading to an A•T to G•C base pair conversion during subsequent cell divisions. ABEs do not require UGI as inosine is not efficiently recognized by DNA repair machinery [6] [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Base Editor Classes and Properties

| Property | Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) | Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Deaminase | APOBEC1 (natural) | engineered TadA (evolved) |

| Chemical Conversion | Cytosine → Uracil → Thymine | Adenine → Inosine → Guanine |

| Base Pair Change | C•G to T•A | A•T to G•C |

| Accessory Domain | UGI (uracil glycosylase inhibitor) | Not required |

| First Generation | BE1 (2016) | ABE7.10 (2017) |

| Efficiency in Mammalian Cells | 37% (BE3 average across 6 loci) | ~50% (ABE7.10) |

| Key Challenge | C-G/C-A byproducts, RNA off-targets | Narrower editing window in early versions |

| Optimized Versions | BE4, BE4max, AncBE4max | ABEmax, ABE8e, ABE8s |

Experimental Design and Implementation

Editor Selection and Optimization

The choice of base editor depends on the specific experimental requirements and target sequence context:

CBE vs. ABE Selection: Determine which transition mutation (C•G to T•A or A•T to G•C) is required based on the sequence context and desired amino acid change [6].

PAM Compatibility: Select Cas protein variants based on PAM availability near the target base. Options include SpCas9 (NGG PAM), SpCas9-NG (NG PAM), xCas9 (NG/GAA/GAT PAMs), and Cas12a-based editors (TTTV PAM) [1] [7].

Editing Window Considerations: Design gRNAs that position the target nucleotide within the optimal editing window (typically positions 4-8 for SpCas9-based editors) while minimizing potential bystander edits at adjacent bases of the same type within the window [6].

Delivery Methods and Validation

Efficient delivery and thorough validation are critical for successful base editing experiments:

Plasmid DNA: Most accessible approach but potential for extended editor expression and increased off-target effects [7].

mRNA and gRNA Co-delivery: Enables transient editor expression, reducing off-target risks while maintaining high editing efficiency [6].

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes: Preassembled editor-gRNA complexes offer the most transient activity, potentially minimizing off-target effects while enabling rapid editing [6].

Validation Requirements: Always assess on-target efficiency by Sanger or next-generation sequencing, evaluate potential bystander edits within the editing window, and perform appropriate off-target analyses (GOTI, whole-genome sequencing, or RNA-seq for transcriptome-wide deamination assessment) [1].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Base Editing Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Base Editor Plasmids | BE4max, AncBE4max, ABEmax, ABE8e | Optimized editor expression; improved efficiency and specificity |

| Cas Protein Variants | SpCas9-NG, xCas9, SpRY, SaCas9, LbCas12a | Expanded PAM compatibility for targeting diverse genomic loci |

| Guide RNA Cloning Systems | Multiplex gRNA vectors, U6 expression systems | Efficient gRNA delivery and expression; enable multiplexed editing |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV vectors, Lentiviral particles, Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo and in vitro editor delivery with tissue-specific targeting |

| Validation Tools | Sanger sequencing primers, NGS libraries, UNG inhibition assays | Assessment of editing efficiency, specificity, and product purity |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T, HAP1, iPSCs, Primary cell systems | Model systems for editing optimization and functional assessment |

Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite their transformative potential, base editors face several technical challenges that require careful consideration in experimental design:

Off-Target Editing: Base editors can cause both DNA and RNA off-target modifications. DNA off-targets may occur at partially homologous genomic sites, while RNA off-targets result from promiscuous deaminase activity independent of Cas9 binding [1]. High-fidelity base editor variants with engineered deaminase domains address these concerns through reduced non-specific activity [1] [2].

Bystander Edits: Multiple editable bases within the activity window can lead to unintended concurrent mutations. Strategies to mitigate this include using editors with narrower activity windows or designing gRNAs that position only the desired base within the window [8] [1].

Sequence Context Limitations: Certain sequence motifs (e.g., methylated cytosines for CBEs) may be edited with reduced efficiency. Deaminase engineering and editor architecture optimization can help address these constraints [4].

Delivery Constraints: The relatively large size of base editor constructs (~5-6 kb) presents challenges for packaging into delivery vehicles with limited capacity, such as adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) [1]. Split-intein systems and compact editor variants are being developed to overcome this limitation [2].

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The base editing field continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions emerging:

Therapeutic Translation: Multiple base editing therapies have entered clinical trials, including treatments for sickle cell disease, beta-thalassemia, familial hypercholesterolemia, and T-cell leukemia [2]. The first patient treated with base-edited cell therapy achieved remission from T-cell leukemia, demonstrating the technology's clinical potential [2].

Dual Base Editors: New editors capable of simultaneous cytosine and adenine editing (ACBEs) enable broader editing capabilities within a single system [1] [5].

AI-Guided Optimization: Machine learning approaches are being employed to predict editing outcomes, optimize gRNA design, and engineer novel editor variants with improved properties [9].

Novel Editor Discovery: Bioinformatic mining of microbial diversity has uncovered novel CRISPR systems and deaminases that may enable next-generation editing tools with unique capabilities [9].

The ongoing refinement of base editing technology continues to expand its potential for research and therapeutic applications, solidifying its role as a paradigm-shifting approach in genome engineering.

Base editors represent a revolutionary class of genome engineering tools that enable precise, programmable conversion of single DNA bases without inducing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs), a significant limitation of earlier CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease systems [3]. This core architecture ingeniously fuses a catalytically impaired Cas protein (dCas9) with a deaminase enzyme, all directed by a guide RNA (sgRNA) to a specific genomic locus [3]. The primary advantage of base editors over traditional CRISPR-Cas9 lies in their ability to directly convert one base pair to another without relying on homology-directed repair (HDR), thereby achieving higher efficiency and purity of editing outcomes while minimizing undesirable insertions and deletions (indels) [3]. Initially developed for cytosine (C) to thymine (T) conversions, the toolset has rapidly expanded to include adenine (A) to guanine (G) base editing and more sophisticated prime editing systems [9] [3]. This technical guide delves into the core architecture of these tools, detailing their components, mechanisms, and experimental methodologies, framed within the broader context of their transformative role in genome engineering research and therapeutic development.

Core Components of the Base Editing System

The functionality of base editors hinges on the synergistic interaction of three fundamental components: a catalytically impaired Cas protein, a deaminase enzyme, and a guide RNA. Each component plays a critical and distinct role in ensuring precise and efficient genome editing.

Catalytically Impaired Cas Protein

The foundation of the base editor is a Cas9 protein that has been rendered catalytically "dead" (dCas9) or converted into a nickase (nCas9) through targeted point mutations. The dCas9 variant contains mutations (e.g., D10A and H840A in Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) that abolish its endonuclease activity, meaning it can no longer cleave either strand of DNA [3]. Its primary function is to act as a programmable DNA-binding module, scanning the genome and unwinding the DNA double helix upon recognizing a target sequence adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [10]. This unwinding creates a transient single-stranded DNA region known as the R-loop, which exposes the non-target DNA strand and makes it accessible for the deaminase enzyme to act upon [10]. The use of a nickase (nCas9), which cuts only the non-edited DNA strand, is common in later-generation base editors like BE3. This nick promotes the cell's repair machinery to favor the conversion of the edited base (e.g., U to T) on the opposite strand, thereby increasing editing efficiency [3].

Deaminase Enzyme

The deaminase enzyme is the catalytic heart of the base editor, responsible for the direct chemical conversion of one base to another. These enzymes are typically recruited from the APOBEC (Apolipoprotein B mRNA Editing Enzyme, Catalytic Polypeptide-Like) family for cytosine base editing (CBE) or evolved from the TadA (tRNA adenosine deaminase) enzyme for adenine base editing (ABE) [3].

- Natural Function and Mechanism: APOBEC deaminases, such as APOBEC1, function in innate immunity by deaminating cytidine to uridine in viral cDNA, while AID (Activation-Induced Deaminase) drives antibody diversification through somatic hypermutation in the Ig locus [3]. These enzymes operate by hydrolytically deaminating a cytosine base in single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), converting it to uracil, which is then read as thymine during DNA replication or repair [3].

- Engineering for Enhanced Performance: Natural deaminases have inherent sequence context preferences (e.g., human APOBEC3A prefers UC motifs) that can limit their versatility [11]. Recent advances use AI-driven protein engineering and structure-based design to create enhanced deaminases. For instance, researchers have developed "Professional APOBECs" (ProAPOBECs) with expanded capabilities for C-to-U editing across diverse sequence contexts (GC, CC, AC, UC) and reduced off-target effects by targeting dimerization interfaces [11].

Guide RNA (sgRNA)

The guide RNA (sgRNA) is the navigational system of the base editor. It is a chimeric RNA molecule that combines the functions of the native crRNA and tracrRNA. The ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence at the 5' end of the sgRNA is programmable and determines the specific genomic target site by forming a complementary duplex with the target DNA strand [10] [3]. The secondary stem-loop structures of the sgRNA scaffold are crucial for binding and stabilizing the Cas protein. The binding of the sgRNA to dCas9/nCas9 induces a conformational change that facilitates DNA unwinding, exposing a ~5-nucleotide "editing window" typically located 13-18 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site where the deaminase acts with highest efficiency [3].

Quantitative Data on Base Editing Systems

The performance of base editors is characterized by key metrics such as editing efficiency, editing window, and product purity. The following tables summarize quantitative data for various base editing architectures.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cytosine Base Editor Architectures [10]

| Base Editor Architecture | Average Editing Efficiency (%) | Editing Window (Position from PAM) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BE3 (N-terminal fused) | ~60% | C3-C8 (Peak: C5-C7) | Original high-efficiency editor; requires N-terminal fusion. |

| sgBE-SL4 (SL4+MS2) | ~40% higher than (SL1+MS2)+(SL3+MS2) | C5-C10 | Deaminase tethered to 4th stem-loop; wider window than BE3. |

| (SL1+MS2)+(SL3+MS2) | ~11.55% | Dual peaks at ~C5 and ~C12 | Traditional MS2 recruitment site; lower efficiency. |

Table 2: Advanced Base Editing Platforms and Their Efficiencies [12] [11]

| Platform Name | Type | Key Components | Reported Efficiency/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PERT | DNA Prime Editing | Prime Editor, engineered suppressor tRNA | Restored enzyme activity to 20-70% in human cell models; ~6% in mouse model, nearly eliminating disease. |

| CU-REWIRE4.0 | RNA Base Editing | ePUF10, ProAPOBEC | 82.3% C-to-U editing efficiency on EGFP mRNA; effective in vivo editing in mouse brain and liver. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility in genome engineering research, below are detailed protocols for key experiments involving base editing systems.

Protocol: sgBE System Assembly and Validation

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing and testing a structure-guided base editor (sgBE) where the deaminase is tethered to specific stem-loops of the sgRNA [10].

sgRNA Scaffold Design and Cloning:

- Design sgRNA expression vectors with MS2 RNA aptamer sequences inserted into specific stem-loops (e.g., SL1, SL3, SL4) of the sgRNA scaffold. For example, to create sgBE-SL4, fuse the MS2 sequence to the 4th stem-loop.

- Use site-directed mutagenesis or synthetic gene fragment assembly to generate these constructs within a U6-promoter driven plasmid.

Base Editor Protein Construction:

- Create an expression plasmid for a fusion protein consisting of (from N- to C-terminus): MS2 Coat Protein (MCP) -> linker -> cytidine deaminase (e.g., APOBEC1) -> linker -> uracil DNA glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) -> linker -> nickase Cas9 (nCas9).

- The nCas9 (D10A) is critical for nicking the non-edited strand to improve efficiency.

Cell Transfection and Editing:

- Culture HEK293T cells in standard DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS.

- Co-transfect cells at 70-80% confluency with the sgRNA plasmid and the base editor fusion protein plasmid using a transfection reagent like Lipofectamine 3000.

- Include a positive control (e.g., a standard BE3 editor) and a negative control (e.g., a non-targeting sgRNA).

Harvest and Analysis:

- Harvest cells 72 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify the target genomic locus by PCR and subject the product to Sanger sequencing.

- Quantify base editing efficiency using computational tools like EditR, which can detect and quantify base conversions from Sanger sequencing chromatograms. Editing efficiencies above 5% are generally considered statistically significant in this setup [10].

Protocol: In Vivo RNA Base Editing with CU-REWIRE

This protocol describes the application of the CU-REWIRE system for RNA base editing in a mouse model [11].

Editor Assembly:

- Construct a plasmid expressing the CU-REWIRE fusion protein: an engineered Pumilio/FBF (ePUF10) RNA-binding domain fused to a Professional APOBEC (ProAPOBEC) deaminase.

- The ePUF10 domain is engineered to include an LP peptide insertion in its fourth repeat for improved stability and efficiency.

Vector Packaging and Delivery:

- Package the expression construct into an Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) vector, selecting a serotype (e.g., AAV9) with high tropism for the target tissue (e.g., liver or brain).

- Purify the AAV particles and quantify the viral titer (vector genomes/mL).

Animal Injection and Phenotypic Analysis:

- Systemically administer the AAV (e.g., via tail vein injection for liver targeting or intracerebroventricular injection for brain targeting) to adult mice. Include control groups injected with a non-targeting AAV.

- For a cholesterol-lowering study: Several weeks post-injection, collect blood plasma from treated and control mice. Measure cholesterol levels using a standard enzymatic assay.

- For a neurological disease model: Conduct behavioral tests relevant to the disease phenotype (e.g., social interaction tests for autism models) several weeks post-injection.

Efficiency and Off-Target Assessment:

- Extract total RNA from the target tissue. Reverse transcribe RNA to cDNA.

- Perform deep sequencing (RNA-seq) of the target transcript with at least 50x coverage to quantify the C-to-U editing efficiency at the intended site.

- Analyze the entire transcriptome data from the RNA-seq to identify potential off-target editing events, noting that these are often due to the basal activity of the APOBEC enzyme rather than the PUF targeting domain [11].

Diagrams of Architectures and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core architectures and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Diagram Title: Core Base Editor Architecture

Diagram Title: sgBE Validation Workflow

Diagram Title: CU-REWIRE RNA Editing Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of base editing experiments requires a suite of specific reagents and tools. The table below catalogs essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Base Editing Experiments

| Reagent / Tool Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9/nCas9 Plasmids | Provides the DNA-binding backbone for base editors. | Catalytically impaired (D10A, H840A) or nickase (D10A) versions; from various species (Sp, Sa). |

| Deaminase Expression Constructs | Sources cytidine (APOBEC1, AID) or adenine (TadA) deaminase activity. | Can be wild-type or engineered (e.g., ProAPOBECs); often codon-optimized for mammalian cells. |

| MS2-tagged sgRNA Vectors | Enables deaminase recruitment to specific sgRNA stem-loops (e.g., SL4). | Plasmid with U6 promoter for sgRNA expression; includes MS2 aptamer sequences. |

| MS2 Coat Protein (MCP) Fusions | Links the deaminase to the MS2-tagged sgRNA. | MCP is fused to the deaminase, creating a physical bridge to the sgRNA. |

| UGI (Uracil Glycosylase Inhibitor) | Improves C-to-T editing efficiency by preventing uracil excision. | Included as a domain in the base editor fusion protein (e.g., in BE3, sgBE). |

| AAV Vectors | In vivo delivery of base editor components. | Serotypes (AAV9, AAV-DJ) selected for target tissue tropism; limited packaging capacity. |

| EditR Software | Quantifies base editing efficiency from Sanger sequencing data. | Accessible web tool; calculates percentage of base conversion from chromatogram files. |

Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) represent a groundbreaking class of genome engineering tools that enable precise, programmable conversion of cytosine to thymine (C•G to T•A) without introducing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or requiring donor DNA templates [13]. This technology represents a significant advancement over earlier CRISPR-Cas9 approaches that relied on the inefficient homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway, which often results in low editing efficiency and frequent unintended insertions or deletions (indels) [13]. CBEs have rapidly evolved from research tools to therapeutic agents, with recent clinical applications demonstrating the correction of a fatal genetic condition in a human infant [14].

The core innovation of CBEs lies in their fusion of a catalytically impaired Cas protein with a cytidine deaminase enzyme, typically from the APOBEC (Apolipoprotein B mRNA Editing Catalytic Polypeptide-like) family [15] [13]. This architecture allows targeted chemical modification of single DNA bases through a multi-step mechanism that harnesses and directs natural cellular processes. The development of CBEs has expanded the CRISPR toolbox beyond disruptive cutting toward precision editing, enabling single-nucleotide changes with efficiencies exceeding 50% at many genomic loci while maintaining low indel rates typically below 1.5% [13].

Core Mechanism of C•G to T•A Conversion

The conversion of C•G to T•A by CBEs occurs through a coordinated biochemical process involving multiple enzyme activities and cellular repair pathways. The mechanism can be dissected into four primary stages: target localization, cytosine deamination, uracil processing, and DNA repair.

Target Localization and ssDNA Exposure

CBEs utilize a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct a Cas9 nickase (nCas9) fusion protein to a specific genomic locus [15]. Upon binding, nCas9 partially unwinds the DNA duplex, exposing a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) bubble on the non-target strand. This exposed ssDNA region, typically 5-10 nucleotides in length and positioned within a defined "editing window" approximately 13-17 nucleotides upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site, becomes accessible to the deaminase domain [15] [16].

Cytosine Deamination to Uracil

The cytidine deaminase domain (e.g., APOBEC3A, APOBEC1, or Sdd7) catalyzes the hydrolytic deamination of cytosine to uracil within the exposed ssDNA window [15] [17]. This chemical conversion changes the base pairing properties: cytosine naturally pairs with guanine, while uracil pairs with adenine. The deamination reaction proceeds through a zinc-dependent mechanism where a water molecule attacks the cytosine ring at the C4 position, leading to the release of ammonia and formation of uracil [18].

Uracil Protection and Strand Nicking

To preserve the uracil intermediate and prevent its removal by cellular repair machinery, CBEs incorporate one or more copies of the uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) protein [15] [14] [13]. UGI binds to and inhibits endogenous uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG), which would otherwise excise uracil to initiate error-prone base excision repair that could lead to undesirable C-to-non-T outcomes or indels [15] [14]. Simultaneously, the nCas9 domain creates a single-strand nick in the non-edited DNA strand (the strand complementary to the uracil-containing strand) [13].

DNA Repair and Mutation Fixation

The combination of the U•G mismatch and the strategically placed nick triggers cellular DNA repair processes that favor the installation of a thymine in place of the original cytosine [15]. The nick is interpreted by the cellular machinery as indicating the U-containing strand as the template strand for repair. During subsequent replication or repair, the U•G mismatch is resolved to U•A, and then to T•A after another round of replication [13]. Alternatively, the nicked strand may be repaired using the uracil-containing strand as a template, directly converting the G to an A on the complementary strand [13].

Table: Key Components of Cytosine Base Editors and Their Functions

| Component | Structure/Type | Function in C•G to T•A Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytically impaired Cas | Cas9 nickase (nCas9) | Binds target DNA via gRNA complementarity; nicks non-edited strand to bias repair |

| Cytidine deaminase | APOBEC3A, APOBEC1, Sdd7, A3B-CTD | Converts cytosine to uracil in exposed ssDNA editing window |

| UGI | One or more protein domains | Inhibits uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG) to prevent uracil excision and increase C-to-T product purity |

| Nuclear localization signal | Peptide sequence | Directs the editor to the nucleus |

| Linkers | Flexible peptide sequences | Connects protein domains and affects editing window properties |

The DNA repair pathways that process the U•G mismatch significantly influence editing outcomes. Recent research has identified that mismatch repair (MMR) factors, particularly the MutSα complex (MSH2/MSH6 heterodimer), facilitate C•G to T•A outcomes [15]. In contrast, alternative repair pathways involving RFWD3 (an E3 ubiquitin ligase) can lead to C•G to G•C transversions, while XPF (a 3'-flap endonuclease) and LIG3 (a DNA ligase) can repair the intermediate back to the original C•G base pair [15].

Diagram Title: Core Mechanism of C•G to T•A Conversion by CBEs

Quantitative Comparison of CBE Platforms

The field has witnessed rapid development of diverse CBE platforms with varying editing characteristics, efficiencies, and specificities. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for prominent CBE systems.

Table: Performance Comparison of Major CBE Platforms

| Editor Name | Deaminase Source | Average C•G to T•A Efficiency | Editing Window | Sequence Context Preference | Key Features/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE3 | rAPOBEC1 | ~30% | Positions ~4-8 | Weak TC preference | First-generation editor; significant indels (~1.1%) and byproducts [13] |

| BE4max | rAPOBEC1 | 56.7% ± 3.3% | Positions ~2-11 | TC preference | Improved version with 2x UGI; reduced C-to-G/A byproducts [17] [13] |

| eA3A-BE3 | Engineered A3A (N57G) | Similar to BE3 on TC motifs | Positions ~5-9 | Strong TCR>TCY>VCN hierarchy | High precision; >40-fold improved precision at certain sites [16] |

| Sdd7 | Engineered Sdd7 | 60.1% ± 2.4% | Broad (positions ~2-14) | Minimal sequence preference | High activity but increased bystander and off-target editing [17] |

| Sdd7e1/e2 | Engineered Sdd7 variants | Maintains high efficiency | Narrowed | Minimal sequence preference | Reduced bystander editing; improved specificity [17] |

| CBE-T | Engineered TadA | Comparable to BE4 | More precise than BE4 | Flexible sequence preferences | Lower off-targets; uses evolved TadA variants [19] |

| A3B-CBE | A3B-CTD | Varies by site | Positions ~4-9 | Prefers 4-nt hairpin loops | Nuclear localization; hairpin loop preference [20] |

Advanced CBE Engineering and Optimization Strategies

Deaminase Engineering for Enhanced Specificity

Recent advances in CBE technology have focused on addressing limitations such as bystander editing (modification of non-target cytosines within the editing window) and off-target activity. Protein engineering approaches have yielded deaminase variants with improved properties:

Engineered A3A (eA3A): Structure-guided mutations (e.g., N57G, Y130F) in human APOBEC3A restore strong sequence preference (TCR>TCY>VCN), dramatically reducing bystander editing while maintaining efficiency on cognate motifs [16]. For example, eA3A-BE3 corrected a human beta-thalassemia promoter mutation with >40-fold higher precision than BE3 [16].

Sdd7 variants: Rational engineering of Sdd7 through mutations at positions V132L, R119A, and R153A reduced bystander editing upstream of the protospacer while maintaining high on-target efficiency [17]. Combination variants (e.g., V132L+R153A) nearly eliminated bystander edits while preserving robust on-target activity [17].

TadA-derived CBEs: Directed evolution of the adenine deaminase TadA created variants capable of efficient cytosine deamination [19]. These CBE-T editors demonstrate comparable on-target efficiency to BE4 but with a more precise editing window, reduced guide-dependent off-target editing, and no detectable gRNA-independent genome-wide off-target editing [19].

Delivery Methods and Format Optimization

Delivery method significantly impacts CBE performance and specificity:

Plasmid DNA: Convenient but associated with extended editor expression, increasing off-target risks [14].

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes: Direct delivery of preassembled editor protein with gRNA reduces off-target effects and avoids DNA integration concerns [14]. Purification challenges have been addressed through optimized expression in E. coli and inclusion of solubility tags [14].

Engineered virus-like particles (eVLP): Delivery of Sdd7e1/e2 via eVLP further improved specificity, nearly eliminating bystander edits and increasing precise single-point mutations [17].

Editing Window Modulation

Strategies to narrow the editing window improve precision when multiple cytosines are present in the target region:

SSB fusions: Fusion of phage-derived single-stranded DNA binding proteins (SSB) to the CBE N-terminus narrowed the editing window by occluding portions of the target sequence [14]. Placement at the N-terminus maintained efficient editing while intermediate positioning often abolished activity [14].

Linker optimization: Modifying linkers connecting deaminase to Cas9 affects editing window size and position [13].

Deaminase mutations: Specific mutations (e.g., in YE1-BE3) can narrow the editing window to approximately three nucleotides but may reduce overall efficiency [16].

Experimental Protocol for CBE Evaluation

Mammalian Cell Editing Protocol

The following protocol represents a standard methodology for evaluating CBE performance in human cell lines:

Materials:

- CBE expression plasmid (e.g., BE4max, eA3A-BE3, or Sdd7 variants)

- gRNA expression plasmid or synthetic gRNA

- HEK293T cells (or other relevant cell lines)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., PEI, Lipofectamine)

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents for target amplification

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Cell culture: Maintain HEK293T cells in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Transfection: Seed cells at 60-70% confluence in 24-well plates. Co-transfect 500 ng CBE plasmid and 250 ng gRNA plasmid using appropriate transfection reagent according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Harvest: 72 hours post-transfection, harvest cells and extract genomic DNA using commercial kits.

- Target amplification: Design primers flanking the target site and amplify by PCR with barcoded primers for multiplexing.

- Sequencing and analysis: Perform amplicon sequencing on an Illumina platform. Analyze sequencing data using appropriate base editing analysis tools (e.g., BE-Analyzer, CRISPResso2) to quantify editing efficiency, product purity, and indel frequency.

Analysis metrics:

- Editing efficiency = (Number of reads with C•G to T•A conversion) / (Total reads) × 100%

- Product purity = (C•G to T•A conversions) / (All observed edits at target site) × 100%

- Bystander editing ratio = (Editing at non-target C) / (Editing at target C)

Off-Target Assessment Methods

gRNA-independent off-target assessment (R-loop assay):

- Transfect cells with CBE plasmid, gRNA, catalytically inactive SaCas9 (dSaCas9), and saCas9 gRNA to create artificial R-loop structures [17].

- Amplify and sequence known R-loop formation sites at endogenous genomic loci.

- Compare C•G to T•A frequencies between CBE variants and negative controls.

Genome-wide off-target assessment:

- Use orthogonal methods such as whole-genome sequencing of edited clones.

- Apply specialized assays like UPD-seq (uracil pull-down sequencing) to map genome-wide uracil incorporation [20].

Research Reagent Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents for CBE Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBE Plasmids | BE4max, eA3A-BE3, Sdd7e1, CBE-T | Provide base editor expression | Available from AddGene; codon-optimized for mammalian cells [17] [16] [13] |

| gRNA Expression Systems | U6-promoter driven vectors, synthetic gRNAs | Target editor to specific genomic loci | Synthetic gRNAs preferred for RNP delivery [14] |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T, K562, SKOV3, primary T cells | Evaluation of editing efficiency and specificity | Primary cells important for therapeutic relevance [19] [17] |

| Delivery Reagents | PEI, Lipofectamine, electroporation kits | Introduce editors into cells | Electroporation preferred for RNP delivery [14] |

| Analysis Tools | Next-generation sequencer, BE-Analyzer software | Quantify editing outcomes | Amplicon sequencing depth >10,000x recommended [17] |

| Control Plasmids | GFP expression vectors, inactive CBE variants | Experimental controls | Essential for normalizing transfection efficiency [16] |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

CBEs have demonstrated significant potential in both basic research and therapeutic applications. Recent advances include:

Therapeutic genome editing: CBEs have entered clinical trials and have been used to correct a fatal genetic condition in a human infant, with marked clinical improvement reported [14].

Primary cell engineering: CBE-T editors demonstrated robust activity in primary T cells and hepatocytes, validating their potential as therapeutic gene-editing tools [19].

Dual base editors: Development of CABE-Ts that catalyze both A-to-I and C-to-U editing using a single TadA variant enables programmable installation of all transition mutations with a single editor [19].

RNA base editing: Engineered APOBEC variants (ProAPOBECs) fused with PUF proteins enable efficient C-to-U RNA editing with therapeutic potential demonstrated in mouse models of hypercholesterolemia and autism spectrum disorder [11] [21].

The future of CBE technology will likely focus on further enhancing specificity, expanding targeting scope through novel Cas variants with diverse PAM preferences, and improving delivery efficiency for therapeutic applications. As the understanding of DNA repair pathways involved in base editing outcomes deepens, more sophisticated editors that can precisely control editing outcomes will continue to emerge.

Genome engineering research has been transformed by the development of base editors, a class of precision tools that enable direct, irreversible conversion of one DNA base pair into another without inducing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or requiring donor DNA templates [13]. Unlike early CRISPR applications that relied on the low-efficiency homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway, base editors operate through chemical modification of nucleobases within DNA, effectively sidestepping the predominant non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway that often introduces unpredictable insertions and deletions (indels) [13]. Among these revolutionary tools, Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) specifically catalyze the conversion of A•T base pairs to G•C, representing a powerful approach for correcting the most common type of pathogenic single-nucleotide variants in humans [13] [22].

The Molecular Architecture of ABEs

Adenine Base Editors are fusion proteins comprising three essential components:

A catalytically impaired Cas9 variant: Typically a nickase (nCas9) that cleaves only the DNA strand containing the guide RNA complement (target strand) but leaves the other strand (non-target strand) intact [22]. This nicking activity is crucial for enhancing editing efficiency.

An engineered tRNA adenosine deaminase: The laboratory-evolved TadA (tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase) domain that performs the central catalytic function of deaminating adenosine [13] [22].

A guide RNA (gRNA): The RNA component that programs the Cas9 moiety to target specific genomic loci through complementary base pairing [22].

The development of ABEs presented a unique challenge as no natural DNA adenine deaminases were known to exist. This obstacle was overcome through extensive directed evolution of the native bacterial tRNA adenosine deaminase TadA, which naturally deaminates adenosine to inosine at the wobble position 34 of tRNAᵃʳᵍ [13] [22]. After seven rounds of molecular evolution, researchers obtained functional ABEs, with the most active initial variant (ABE7.10) displaying an average editing efficiency of 53% with an editing window spanning protospacer positions 4-7 [13].

Table 1: Evolution of Adenine Base Editors

| Generation | Key Features | Editing Efficiency | Editing Window | Notable Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABE7.10 | First functional ABE from directed evolution | ~53% average | Positions 4-7 | Foundation for all subsequent ABEs |

| ABEmax | Improved nuclear localization and codon usage | 1.3-1.5x ABE7.10 | Positions 4-7 | Better expression and nuclear targeting |

| ABE8e | TadA-8e (V106W) variant from phage-assisted evolution | ~590-fold faster than ABE7.10 [13] | Wider activity window | Dramatically accelerated deamination kinetics |

| ABE8s | 40 new variants from further evolution | 98-99% in primary T cells [13] | Expanded window (positions 3-10) | High efficiency in therapeutically relevant cells |

The Stepwise Molecular Mechanism of A•T to G•C Conversion

The process of adenine base editing involves a precisely coordinated sequence of molecular events:

Target Recognition and R-loop Formation

The Cas9-gRNA complex identifies target genomic DNA by locating a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence—for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), this is a 5'-NGG sequence [22]. Upon PAM recognition, the Cas9-gRNA complex initiates DNA unwinding, verifying complementarity between the gRNA and the target DNA strand. This process results in the formation of an R-loop structure, where the target strand forms a stable heteroduplex with the gRNA, while the non-target strand becomes temporarily displaced as a flexible single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) [22] [23].

Deoxyadenosine Deamination in the Single-Stranded DNA

The displaced non-target strand ssDNA within the R-loop becomes accessible to the engineered TadA deaminase domain of the ABE. TadA catalyzes the hydrolytic deamination of deoxyadenosine (dA) to deoxyinosine (dI) [22]. This conversion represents the central chemical transformation in adenine base editing. Structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy have revealed that ABE8e, one of the most efficient ABE variants, accelerates DNA deamination by up to ~1100-fold compared to earlier ABEs, primarily due to mutations that stabilize DNA substrates in a constrained, transfer RNA-like conformation [23].

DNA Strand Nicking and Cellular Repair

The nCas9 domain of the ABE then nicks the target DNA strand (the strand complementary to the edited strand) [22]. This strategic nicking of the unedited strand triggers cellular DNA repair mechanisms that perceive the nicked strand as "newly synthesized" and in need of correction. Consequently, the cell uses the edited strand (containing dI) as a template for repair [13].

DNA Replication and Permanent Base Pair Conversion

During subsequent DNA replication or repair, the deoxyinosine (dI) in the edited strand is interpreted by DNA polymerases as deoxyguanosine (dG), and thus pairs with cytosine [22]. After a second round of DNA replication, this results in a permanent A•T to G•C base pair conversion at the target site [13] [22].

Diagram Title: ABE Molecular Mechanism

Structural Basis of Engineered TadA Function

The remarkable efficiency of evolved TadA variants stems from specific structural modifications that enable DNA deamination. Wild-type EcTadA forms homodimers and specifically recognizes the rigid structure of tRNA anticodon stems with the U³³(-1)A³⁴(0)C³⁵(+1)G³⁶(+2) sequence in the anticodon loop [22]. Cryo-EM structures of ABE8e in DNA-bound states reveal that:

- Directed evolution introduced mutations primarily in substrate-binding loops and the C-terminal α5-helix, enabling recognition of ssDNA rather than tRNA [22].

- Despite significant functional changes, the overall 3D structure of evolved TadA8e remains comparable to wild-type EcTadA, suggesting optimization rather than complete restructuring of the active site [22].

- The homodimer interface (composed of α2, α3, and α4 helices) remains largely preserved, though the functional significance of dimerization in DNA deamination requires further investigation [22].

- Upon binding, the flexible ssDNA substrate acquires a U-turn conformation that positions the target adenine optimally for deamination [22].

Table 2: Key TadA Mutations and Their Functional Impacts in ABE Development

| Residue | Wild-type | Evolved (ABE8e) | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 106 | Ala | Val/Trp (ABE8e) | Alters substrate specificity and processivity [13] |

| 108 | Asp | Asn | Enhances DNA binding and catalytic efficiency |

| Other mutations | Various | 20 total substitutions in ABE8e | Optimize active site, improve ssDNA binding, and increase deamination rate [22] |

Experimental Approaches for ABE Development and Analysis

Directed Evolution of TadA

The development of advanced ABE variants employed sophisticated phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE) systems [13]. In this approach:

- The evolving TadA gene is encoded on a selection phage that infects E. coli host cells.

- Host cells contain accessory plasmids that establish a selection circuit regulating gene III expression, which is essential for phage replication.

- Only phage encoding TadA variants with desired deamination activity trigger production of gene III product, enabling selective propagation of improved variants [24].

- Under constant mutagenesis and dilution, phage lacking desired activity are rapidly diluted out, while beneficial mutations persist and accumulate [24].

Assessment of Base Editing Efficiency

Robust experimental protocols are essential for characterizing ABE performance:

Cell Culture Transfection:

- HEK293T cells are commonly used for initial screening

- Cells are transiently co-transfected with ABE expression vectors and guide RNA plasmids

- Editing efficiency is assessed 72-96 hours post-transfection [25]

High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis:

- Genomic DNA is extracted from transfected cells

- Target regions are amplified via PCR and subjected to next-generation sequencing

- Base editing efficiency is quantified using tools like CRISPResso2 [25]

Off-Target Assessment:

- RNA sequencing evaluates transcriptome-wide off-target RNA editing

- Whole-genome sequencing detects DNA-level off-target effects

- γH2AX immunofluorescence or Western blotting assesses genotoxicity and DNA damage response [26]

Advanced ABE Engineering and Future Directions

Dual-Function Base Editors

Recent engineering efforts have successfully created dual base editors that combine the functions of both adenine and cytosine editing. Notably, TadA has been further engineered to generate:

- TadCBEs: TadA-derived cytosine base editors that convert C•G to T•A with high efficiency and low off-target activity [24].

- TadDE: A TadA dual base editor that performs equally efficient cytosine and adenine base editing [24].

- CABE-Ts: Cytosine and adenine base editors utilizing a single TadA variant (TADAC) that catalyzes both A-to-I and C-to-U editing, creating a more compact editor approximately 700 bp smaller than previous dual editors [19].

Chromatin-Modulating Fusion Proteins

Research has demonstrated that fusion of chromatin-associated factors such as HMGN1 can enhance ABE efficiency. HMGN1-fused ABE (HMGN1-A8e) showed modestly higher editing efficiency at most tested loci, with average increases of up to 37.40% at certain sites, likely through increased chromatin accessibility [25].

Clinical Applications and Trials

ABEs have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential in clinical settings:

- Primary T cell editing: ABE8 variants achieved 98-99% target modification in primary T cells, making them promising tools for cell therapy applications [13].

- In vivo therapies: Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery of ABEs enables systemic administration, as demonstrated in clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) where participants showed ~90% reduction in disease-related protein levels [27].

- Rare genetic diseases: The first personalized in vivo CRISPR treatment was successfully administered to an infant with CPS1 deficiency, establishing a regulatory pathway for rapid approval of genome editing therapies [27].

Diagram Title: ABE Engineering Evolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ABE Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for ABE Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ABE Plasmids | Expression of base editor components | ABE7.10, ABE8e, ABEmax; often with codon optimization for mammalian cells |

| Guide RNA Vectors | Target specificity determination | U6-promoter driven sgRNA expression cassettes |

| Cell Lines | In vitro editing assessment | HEK293T (screening), primary T cells, HSPCs (therapeutic relevance) |

| Delivery Methods | Introducing editors into cells | Lipid nanoparticles (LNP) for in vivo work; electroporation for ex vivo editing |

| Analysis Tools | Quantifying editing outcomes | CRISPResso2, next-generation sequencing, γH2AX staining for genotoxicity |

| Target Validation | Confirming editing specificity | RNA-seq for transcriptome-wide off-target assessment; WGS for DNA off-targets |

Adenine Base Editors represent a landmark advancement in genome engineering, offering unprecedented capability for precise A•T to G•C conversion without inducing double-strand breaks. Through sophisticated protein engineering of TadA deaminases, researchers have developed increasingly efficient and specific editors with expanding therapeutic applications. The modular nature of ABEs continues to inspire new engineering approaches, including dual-function editors and chromatin-modulating fusions, ensuring that this technology will remain at the forefront of precision genome editing for both basic research and clinical applications.

The Critical Role of the Uracil Glycosylase Inhibitor (UGI) in Enhancing CBE Efficiency

Base editing represents a significant evolution in the field of genome engineering, enabling precise, single-nucleotide changes without inducing double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) associated with traditional CRISPR-Cas9 editing [28] [6]. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) are a class of these tools designed specifically for converting cytosine (C) to thymine (T) through a multi-step biochemical process [3] [6]. The core architecture of a CBE typically consists of a catalytically impaired Cas9 variant (such as nickase Cas9 or dCas9) fused to a cytidine deaminase enzyme [6].

The editing process begins when the CBE complex binds to DNA at a target site specified by the guide RNA (gRNA). The cytidine deaminase component then acts on a single-stranded DNA region within an "editing window," converting cytosine to uracil [29] [6]. This uracil intermediate is structurally similar to thymine and pairs with adenine during DNA replication. However, a fundamental cellular defense mechanism recognizes this uracil as DNA damage and initiates base excision repair (BER) to restore the original cytosine, thereby undermining the editing efficiency [30] [3]. It is at this critical juncture that the uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) plays its indispensable role by blocking this repair pathway and ensuring the persistence of the edited base.

Molecular Mechanism of UGI Action

Structural Basis of UGI-Mediated Inhibition

UGI is a small, thermostable protein (84 amino acids in its native form from Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage PBS2) that acts as a potent and specific inhibitor of uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) [31] [32]. The molecular mechanism of inhibition has been elucidated through high-resolution crystal structures of UGI complexed with human and E. coli UDG [31] [32].

UGI achieves remarkable inhibition through protein mimicry of DNA. The UGI structure consists of a twisted five-stranded antiparallel beta sheet and two alpha helices [31]. During complex formation, UGI inserts a beta strand into the conserved DNA-binding groove of UDG without contacting the uracil specificity pocket [31]. This interface buries over 1200 Ų on UGI and is characterized by shape and electrostatic complementarity, specific charged hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic packing [31].

Notably, UGI most closely resembles a midpoint in the trajectory between B-form DNA and the kinked DNA observed in UDG:DNA product complexes, making it a transition-state mimic for UDG-flipping of uracil nucleotides from DNA [32]. This exquisite structural mimicry enables UGI to effectively compete with DNA substrates for the UDG active site, forming a very high-affinity complex that irreversibly inhibits the enzyme's activity [31] [32].

The UGI-UDG Interaction Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the competitive inhibition mechanism through which UGI blocks the base excision repair pathway, thereby ensuring the success of C•G to T•A base conversion:

Figure 1: UGI Inhibition of UDG in the Base Editing Pathway. UGI acts as a competitive inhibitor of UDG, preventing the initiation of base excision repair and allowing the uracil intermediate to be processed as thymine during DNA replication.

Historical Development and Optimization of UGI-Enhanced CBEs

Evolution of CBE Generations

The integration of UGI into base editing systems has evolved through several generations, each demonstrating improved editing efficiency and specificity:

First-Generation Base Editors (BE1): The initial CBE design featured a fusion of rat APOBEC1 cytidine deaminase to dCas9, which catalyzed the conversion of cytosine to uracil but suffered from low efficiency due to active uracil excision by endogenous UDG [3].

Second-Generation Base Editors (BE2): This iteration incorporated a single UGI unit fused to the C-terminus of dCas9, resulting in significantly enhanced C-to-T editing efficiency by blocking uracil excision [3].

Third-Generation Base Editors (BE3): The current standard configuration utilizes Cas9 nickase (nCas9) instead of dCas9, with UGI fused to the C-terminus. The nickase activity creates a single-strand break in the non-edited strand, which biases cellular repair mechanisms to replace the G opposite the U with an A, further improving editing efficiency [3] [6].

Advanced CBE Architectures: Recent developments have explored novel UGI placements, including internal fusion within the nCas9 architecture. A 2025 study demonstrated that relocating UGI to position 1282 within nCas9 maintained robust on-target editing while substantially reducing Cas9-dependent DNA off-target activity [30].

Quantitative Impact of UGI on Editing Outcomes

Table 1: Comparative Performance of CBE Variants With and Without UGI

| CBE Variant | UGI Configuration | Average C-to-T Efficiency | C-to-A/C-to-G Indels | Cas9-Dependent Off-Target Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE1 (no UGI) | None | <10% | Not reported | Not assessed | [3] |

| BE2 | Single C-terminal UGI | ~15-20% | Reduced | Not assessed | [3] |

| BE3 | Single C-terminal UGI | ~30-50% | Minimized | Moderate | [3] [6] |

| YE1-no UGI | None | 12.6% | 45.1% total (C-to-A: 8.8%, C-to-G: 36.3%) | Not specified | [30] |

| YE1-UGI-C (Classical) | Single C-terminal UGI | 91.7% | <3% total | Substantial | [30] |

| YE1-UGI-1282 | Internal UGI (position 1282) | 84.3% | <1% total | Dramatically reduced | [30] |

The quantitative data clearly demonstrates that UGI inclusion is essential for achieving high-efficiency C-to-T conversion while minimizing undesired editing byproducts. The internal fusion strategy represents a particularly promising advancement for therapeutic applications where off-target effects present significant safety concerns.

Advanced UGI Engineering Strategies

Spatial Optimization of UGI Placement

Recent research has focused on optimizing UGI placement within the CBE architecture to enhance specificity. A comprehensive study published in Scientific Reports in 2025 systematically evaluated UGI relocation through internal fusion within nCas9 [30]. Researchers generated 23 distinct YE1-UGI-X CBE variants with UGI inserted at different positions within nCas9 and compared them to classical C-terminal UGI fusion.

The screening revealed that 20 out of 23 YE1-UGI-X variants maintained robust on-target editing (>50% C-to-T conversion) while 20/23 variants exhibited significantly reduced Cas9-dependent off-target activity [30]. The most promising construct, YE1-UGI-1282, demonstrated dramatic reductions in off-target editing across all examined loci while maintaining high on-target efficiency [30].

Notably, the selectivity ratios (on-target/off-target) of YE1-UGI-1282 exhibited 37- to 104-fold improvements over the classical YE1 system, establishing an alternative engineering paradigm for developing high-fidelity CBEs [30].

Split-UGI and Multiplexed Configurations

Further engineering explorations have investigated the use of P2A-linked UGI constructs that effectively create a split-Cas9 system [30]. Among 23 engineered YE1-2A-UGI-X CBE variants, 16 constructs retained robust on-target editing (>50% C-to-T conversion), with 21/23 variants showing significantly reduced Cas9-dependent off-target activity compared to the C-terminal UGI control [30].

The effective positions for UGI integration differed between conventional fusion and P2A-linked constructs, suggesting that the separation of protein fragments necessitates additional structural and functional assembly to achieve efficient editing at target sites [30].

Table 2: Comparison of UGI Engineering Strategies in CBEs

| Engineering Strategy | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-Terminal Fusion (Classical BE3) | Single UGI fused to nCas9 C-terminus | High on-target efficiency, established protocol | Substantial Cas9-dependent off-target effects | Moderate (requires careful off-target assessment) |

| Internal Fusion (YE1-UGI-1282) | UGI inserted at specific internal nCas9 sites | High on-target efficiency with dramatically reduced off-target effects | Requires extensive screening for optimal positions | High (improved safety profile) |

| Split-UGI with P2A Linker | P2A peptide creates separate but linked UGI | Reduced off-target effects, flexible configuration | Potential for decreased overall editing efficiency | Moderate to High (dependent on specific application) |

| UGI Dimer/Multimer | Multiple UGI units in tandem | Potentially enhanced UDG inhibition | Increased construct size, possible steric hindrance | Moderate (packaging challenges for viral delivery) |

Experimental Protocols for UGI-Enhanced CBE Evaluation

Protocol: Assessing CBE Efficiency with UGI Components

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the editing efficiency and specificity of UGI-enhanced CBEs at endogenous genomic loci.

Materials:

- CBE plasmid constructs (with and without UGI)

- HEK293T or other suitable cell line

- Target-specific sgRNAs

- Lipofectamine 3000 or similar transfection reagent

- PCR reagents and genomic DNA extraction kit

- High-throughput sequencing platform

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Maintain HEK293T cells in appropriate medium. Seed cells in 24-well plates at 70-80% confluence. Transfect with CBE constructs (with and without UGI) and target-specific sgRNAs using Lipofectamine 3000 according to manufacturer's protocol [30].

- Genomic DNA Extraction: 72 hours post-transfection, harvest cells and extract genomic DNA using commercial kits.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers flanking the target region and amplify by PCR. Include barcodes for multiplexed sequencing.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Purify PCR products and subject to next-generation sequencing (Illumina MiSeq or similar platform).

- Data Analysis: Process sequencing data using appropriate bioinformatics tools (CRISPResso2, BEAT, etc.) to quantify:

- C-to-T conversion efficiency at target site

- Presence of bystander edits within the activity window

- Indel formation rates

- Non-C-to-T conversion products (C-to-A, C-to-G)

Expected Results: UGI-containing CBEs should demonstrate significantly higher C-to-T conversion efficiency (>30%) compared to non-UGI controls, with minimal non-C-to-T byproducts [30].

Protocol: Evaluating Off-Target Effects of UGI-Enhanced CBEs

Objective: To assess Cas9-dependent and Cas9-independent off-target effects of different UGI-CBE configurations.

Materials:

- Engineered CBE variants (classical and internally-fused UGI)

- Validated off-target sgRNAs for known loci (e.g., EMX1-OT2, HEK4-OT2) [30]

- Control sgRNAs with minimal off-target potential

- Rest of materials as in Protocol 5.1

Methodology:

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cells with CBE variants and both on-target and validated off-target sgRNAs as described in Protocol 5.1.

- Amplification of Off-Target Loci: Design primers for known off-target sites based on previous studies or computational predictions [30].

- Deep Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing of both on-target and off-target loci.

- Comprehensive Analysis: Calculate editing efficiencies at all examined loci and determine selectivity ratios (on-target/off-target efficiency).

Expected Results: Classical C-terminal UGI fusions typically exhibit substantial off-target activity (e.g., 30-40% at validated off-target sites), while internally-fused UGI variants (e.g., YE1-UGI-1282) should show dramatically reduced off-target editing (e.g., <5%) while maintaining high on-target efficiency [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for UGI-CBE Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for UGI and CBE Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editor Plasmids | BE3, BE4, YE1-based constructs [30] [3] | Core editor components for C-to-T conversion | Available from Addgene; BE3 is most widely validated |

| UGI Variants | Wild-type UGI, UGI mutants, split-UGI configurations [30] | Inhibition of uracil excision repair | C-terminal fusion is standard; internal fusions show improved specificity |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T, HeLa, HAP1, iPSCs [33] | Evaluation of editing efficiency and specificity | HEK293T recommended for initial testing due to high transfection efficiency |

| Delivery Systems | Lipofectamine 3000, PEI-based nanoparticles [34], AAV vectors [35] | Introduction of editing components into cells | Non-viral methods suitable for research; AAV necessary for therapeutic applications |

| Analysis Tools | CRISPResso2, BEAT, targeted deep sequencing [30] | Quantification of editing efficiency and off-target effects | Amplicon sequencing required for precise quantification of base conversions |

| UDG Assay Kits | Commercial UDG activity assays | Validation of UGI functionality | Useful for confirming UGI activity in novel constructs |

The uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) plays an indispensable role in cytosine base editing by fundamentally altering the cellular response to the engineered uracil intermediate. Through its remarkable structural mimicry of DNA and competitive inhibition of UDG, UGI ensures that the deaminated cytosine persists through DNA replication to become a permanent T•A base pair [31] [32].

Recent advances in UGI engineering, particularly the strategic relocation of UGI within the Cas9 architecture, have demonstrated that spatial organization can significantly influence both on-target efficiency and off-target specificity [30]. The development of internally-fused UGI-CBE variants represents a promising direction for therapeutic applications where minimizing off-target effects is paramount.

As base editing continues to transition from research tool to clinical therapeutic—evidenced by the recent FDA approval of the first CRISPR-based therapy [28]—further optimization of UGI components and their integration into editing complexes will be essential. Future research directions include engineering UGI variants with enhanced inhibition potency, developing systems with tunable UGI activity for transient versus permanent inhibition, and creating novel architectures that optimize the size constraints of viral delivery vectors [35] [30]. Through these continued innovations, UGI-enhanced base editors will remain at the forefront of precise genome engineering for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

Base editing represents a significant leap forward in the field of genome engineering, enabling precise, single-nucleotide changes without inducing double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) [36] [8]. This technology combines the targeting specificity of CRISPR systems with the chemical conversion capabilities of deaminase enzymes, addressing the critical need for tools that can efficiently correct point mutations, which account for approximately 60% of known human disease-causing variants [37] [6]. The foundational adenine and cytosine base editors have undergone rapid evolution, yielding advanced platforms such as the ABE8 series and BE4max variants that offer dramatically improved editing efficiency, precision, and therapeutic potential [38] [37] [39]. This review examines the molecular architecture, functional improvements, and experimental applications of these advanced base editors, providing researchers with a technical guide for their implementation in genome engineering research.

Core Mechanisms of Base Editing

Fundamental Components and Editing Principles

Base editors are fusion proteins that typically consist of three main components: a catalytically impaired Cas protein (either dead Cas9/dCas9 or nickase Cas9/nCas9), a deaminase enzyme, and a guide RNA (gRNA) for target specificity [8] [6]. The mechanism relies on the Cas protein binding to a specific genomic locus directed by the gRNA, which creates an R-loop structure that exposes a single-stranded DNA region. The deaminase enzyme then acts on specific nucleotides within this exposed region, known as the "editing window," typically spanning 5-10 nucleotides [8].

Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) utilize cytidine deaminases (such as APOBEC1) to convert cytosine (C) to uracil (U), which DNA polymerases read as thymine (T) during replication or repair, ultimately resulting in a C•G to T•A base pair conversion [36] [6]. To enhance efficiency, CBEs incorporate uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) to prevent the base excision repair pathway from reversing the U•G mismatch back to C•G [36] [8].

Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) employ engineered adenine deaminases (such as evolved TadA) to convert adenine (A) to inosine (I), which is interpreted as guanine (G) by cellular machinery, resulting in an A•T to G•C base pair conversion [36] [39] [6]. The development of ABEs required extensive protein engineering since no natural DNA adenine deaminases were known to exist [36].

Table 1: Core Components of Advanced Base Editing Systems

| Component | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Protein | DNA binding and localization | nCas9 (D10A), dCas9, Cas12a, SpRY |

| Cytosine Deaminase | Converts C to U | APOBEC1, AncAPOBEC1, YE1, YFE |

| Adenine Deaminase | Converts A to I | TadA-7.10, TadA-8e, TadA-8.17 |

| Inhibitor Domains | Enhances editing efficiency | UGI (uracil glycosylase inhibitor) |

| Nuclear Localization Signals | Directs editor to nucleus | Bipartite NLS (BE4max, ABE8) |

| Guide RNA | Targets specific genomic loci | sgRNA, crRNA |

Visualizing Base Editor Architecture and Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and editing mechanism of a typical base editor:

Advanced Base Editor Platforms

The ABE8 Series: Enhanced Adenine Base Editing

The ABE8 series represents an eighth-generation evolution of adenine base editors developed through directed evolution of the TadA deaminase domain [38] [39]. These editors demonstrate substantial improvements over previous versions:

Enhanced Efficiency: ABE8s show approximately 1.5× higher editing at protospacer positions A5-A7 and 3.2× higher editing at positions A3-A4 and A8-A10 compared to ABE7.10 [38]. In primary human T cells, ABE8s achieve 98-99% target modification efficiency, maintained even when multiplexed across three loci [38].

Reduced Indel Formation: When using catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9), ABE8 constructs demonstrated a 2.1× on-target DNA-editing efficiency while reducing indel frequency by more than 90% compared to ABE7.10 [39].

Broadened PAM Compatibility: ABE8 variants utilizing NG-Cas9 (recognizing NG PAM) and SaCas9 (recognizing NNGRRT PAM) show 1.6× and 2× median increases in editing frequency respectively over ABE7.10 with standard SpCas9 [39].

Reduced Off-Target Effects: ABE8s induce no significant levels of sgRNA-independent off-target adenine deamination in genomic DNA and very low levels of adenine deamination in cellular mRNA when delivered as mRNA [38].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Adenine Base Editors

| Editor | Editing Efficiency | Editing Window | Indel Frequency | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABE7.10 | Baseline | Positions 4-7 (protospacer) | Up to 1.5% | First-generation efficient ABE |

| ABEmax | ~1.3× ABE7.10 | Similar to ABE7.10 | Similar to ABE7.10 | Codon optimization, NLS improvements |

| ABE8e | ~1.8-3.2× ABE7.10 | Positions 3-10 | <0.5% | Eight TadA mutations, monomeric |

| ABE8.17 | ~1.9-3.2× ABE7.10 | Positions 3-10 | <0.5% | High efficiency in primary cells |

| ABE8.17-NL | Similar to ABE8.17 | Positions 2-4 (narrowed) | <0.3% | Linker deletion for precision |

BE4max and AncBE4max: Optimized Cytosine Base Editing

The BE4max and AncBE4max platforms represent fourth-generation cytosine base editors with significant improvements over earlier CBEs:

Enhanced Nuclear Localization: BE4max incorporates bipartite nuclear localization signals at both N and C-termini, improving nuclear import and editing efficiency [37].

Ancestral Deaminase Reconstruction: AncBE4max substitutes rAPOBEC1 with an APOBEC optimized by ancestral sequence reconstruction, resulting in higher editing efficiency and reduced bystander edits [37].

Improved Product Purity: In zebrafish models, BE4max and AncBE4max provide desired base substitutions at similar efficiency to BE3 and Target-AID but without detectable indels [37]. AncBE4max specifically produces fewer incorrect and bystander edits [37].

Precision-Optimized Editors: YFE-BE4max and ABE8.17-NL

Recent engineering efforts have focused on narrowing the editing window to minimize bystander mutations:

YFE-BE4max: This cytosine base editor incorporates three mutations (W90Y + Y120F + R126E) in rAPOBEC1, narrowing the editing window to approximately 3 nucleotides while maintaining high efficiency [40]. In rabbit embryos, YFE-BE4max successfully mediated precise single C-to-T conversions at disease-relevant loci with minimal bystander editing [40].

ABE8.17-NL: By eliminating the linker between the TadA-8.17 and nCas9 domains, researchers created ABE8.17-NL, which achieves efficient base editing within a narrowed window (2-4 nt) in human HEK293FT cells [41]. This modification improves single-base precision while maintaining the high efficiency of the ABE8.17 platform.

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Implementation in Animal Model Systems

Advanced base editors have been successfully deployed across multiple organismal systems for disease modeling and functional studies:

Rabbit Disease Models: ABE8.17 and SpRY-ABE8.17 have been used to efficiently introduce point mutations in rabbits to model human diseases [41]. At the Tyr locus (associated with albinism), ABE8.17 achieved editing efficiencies of 41-72%, while ABE7.10 failed to produce desired edits at the same loci [41]. Similarly, YFE-BE4max was used to introduce precise point mutations in the Lmna gene (associated with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome) in F0 rabbits with high efficiency and precision [40].

Zebrafish Genetic Studies: BE4max and AncBE4max have demonstrated efficient C-to-T conversion in zebrafish using highly active sgRNAs targeting twist and ntl genes [37]. These editors provided desired base substitutions at similar efficiency to previous BE3 and Target-AID plasmids but without detectable indels [37].

Therapeutic Applications in Human Cells

Advanced base editors show remarkable promise for therapeutic genome engineering:

Hemoglobinopathies: ABE8 was used in human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells to recreate a natural allele at the promoter of the γ-globin genes HBG1 and HBG2 with up to 60% efficiency, causing persistence of fetal hemoglobin as a potential treatment for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia [38].

Primary T Cell Engineering: In primary human T cells, ABE8s achieved 98-99% target modification at multiple loci, enabling the generation of universal CAR T cells resistant to PD1 inhibition [38] [39]. This high efficiency was maintained when multiplexed across three loci simultaneously [38].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Base Editing in Mammalian Cells

The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for implementing advanced base editors in mammalian cell systems:

Critical Protocol Steps:

Target Selection and gRNA Design: Identify the target base and ensure a compatible PAM sequence is positioned such that the target base falls within the editor's activity window (typically positions 4-8 for canonical SpCas9-based editors) [36] [8]. For ABE8 editors, the window extends from approximately positions 3-10 [38] [39].

Editor Delivery: For therapeutic applications, mRNA delivery is recommended as it results in more effective on-target editing and reduced off-target editing frequencies compared to plasmid DNA [39]. The use of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes can further enhance specificity.

Validation Methods: Initial screening via Sanger sequencing followed by targeted deep sequencing to quantify editing efficiency, bystander edits, and indel frequencies [37] [40]. Tools like EditR can provide robust base editing quantification from Sanger sequencing data [40].

Off-Target Assessment: Evaluate potential sgRNA-dependent off-target sites through whole-genome sequencing or targeted approaches. For ABE8 editors, the V106W mutation (ABE8.17-m+V106W) can reduce off-target RNA and gRNA-dependent DNA editing while maintaining on-target activity [39].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Base Editing

| Reagent | Source/Identifier | Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|