Boosting CRISPR Efficiency: A Scientist's Guide to Troubleshooting Low Editing Rates

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for diagnosing and resolving low CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency.

Boosting CRISPR Efficiency: A Scientist's Guide to Troubleshooting Low Editing Rates

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for diagnosing and resolving low CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, it synthesizes the latest research on cell-type-specific repair mechanisms, optimized sgRNA design, delivery methods, and chemical enhancers. The article offers actionable strategies for improving knockout and knock-in outcomes, ensuring reliable and reproducible genome editing for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

Understanding the Core Principles of CRISPR-Cas9 Editing and Efficiency Barriers

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary DNA repair pathways activated after a CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand break (DSB), and how do they influence the editing outcome?

After CRISPR-Cas9 creates a DSB, the cell primarily activates two repair pathways [1]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is the dominant and most error-prone pathway. It directly ligates the broken DNA ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). For knockout experiments, this is the desired outcome, as indels can disrupt the gene's reading frame.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This is a precise repair pathway that uses a DNA template (such as a donor DNA molecule) to faithfully repair the break. HDR is less efficient than NHEJ and is restricted to certain cell cycle phases (S/G2), making it challenging for precise knock-in experiments [2].

Q2: Beyond small indels, what are the more complex, unintended on-target consequences of CRISPR-Cas9 editing?

Recent studies reveal that CRISPR-Cas9 can cause significant on-target structural variations (SVs) that are often undetected by standard short-read sequencing [1]. These include:

- Large Deletions: Ranging from kilobases to megabases, which can remove entire genes or critical regulatory elements.

- Chromosomal Translocations: Occur when simultaneous breaks on different chromosomes are incorrectly joined.

- Chromothripsis: A catastrophic event where a chromosome is shattered and reassembled incorrectly.

These SVs raise substantial safety concerns for therapeutic applications, as they could disrupt tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes [1].

Q3: How does the choice of cell type, particularly dividing versus non-dividing cells, affect CRISPR repair outcomes?

DNA repair is not universal across cell types. Postmitotic cells, such as neurons and cardiomyocytes, repair DSBs differently than rapidly dividing cells [2]:

- Repair Kinetics: Indels accumulate over a much longer period (up to two weeks) in neurons, unlike in dividing cells where repair plateaus within days.

- Pathway Preference: Neurons exhibit a narrower distribution of repair outcomes, heavily favoring small indels typical of NHEJ and showing a significantly lower prevalence of the larger deletions associated with microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), a pathway more active in dividing cells [2].

Q4: What strategies can be used to minimize off-target editing?

Several strategies can enhance the specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 [3] [4]:

- High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Use engineered Cas9 nucleases (e.g., HiFi Cas9) designed to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity.

- Optimized gRNA Design: Carefully select gRNAs with high specificity using bioinformatic tools to avoid off-target sites. Chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl analogs) on synthetic gRNAs can also reduce off-target activity.

- Alternative Editors: Consider using base editors or prime editors that do not create DSBs, thereby lowering the risk of off-target effects.

- Delivery Method: Use delivery methods that result in transient expression of CRISPR components (e.g., Cas9 ribonucleoprotein, RNP) to limit the window of opportunity for off-target cutting [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low Knockout Efficiency

Low knockout efficiency is a prevalent problem where an insufficient percentage of cells show gene disruption, leading to weak phenotypes and unreliable data [5].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Suboptimal sgRNA Design: The chosen sgRNA may have low activity or form secondary structures that hinder function [5].

- Solution: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling) to design and select 3-5 highly specific sgRNAs with optimal GC content. Test them empirically to identify the most effective one [5].

- Low Transfection Efficiency: The CRISPR components are not successfully delivered to a high percentage of cells [5].

- Solution: Optimize the delivery method. For hard-to-transfect cells, use electroporation or high-efficiency viral vectors (e.g., lentivirus). Lipid-based transfection reagents (e.g., DharmaFECT, Lipofectamine 3000) can be optimized for other cell types [5].

- Inefficient DNA Repair: The cell's DNA repair machinery may be efficiently repairing the DSBs.

- Solution: Use stably expressing Cas9 cell lines to ensure consistent nuclease activity. The choice of cell line matters, as some (e.g., HeLa) have highly efficient DNA repair systems that can reduce knockout success [5].

- Suboptimal sgRNA Design: The chosen sgRNA may have low activity or form secondary structures that hinder function [5].

Validation Protocol:

- Genotypic Validation: Use T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor assays to detect indels. Confirm with Sanger sequencing and analyze editing efficiency with tools like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) [3].

- Phenotypic Validation: Perform Western blotting to confirm the absence of the target protein or use reporter assays to demonstrate loss of gene function [5].

Issue 2: High Off-Target Activity

Off-target activity occurs when Cas9 cuts at genomic sites similar but not identical to the intended target, potentially confounding experimental results and posing a critical safety risk in therapies [3].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Promiscuous sgRNA: The sgRNA has high similarity to multiple genomic sites.

- Solution: Redesign the sgRNA using prediction tools to minimize off-target potential. Select gRNAs with a high on-target/off-target ratio and consider shorter guide lengths (17-20 nt) to increase specificity [3].

- Prolonged Cas9 Expression: Persistent activity of the Cas9 nuclease increases the chance of off-target cleavage.

- Solution: Deliver CRISPR components as a pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. RNP delivery leads to rapid degradation and a shorter activity window, significantly reducing off-target effects [3].

- Use of Wild-Type Cas9: The standard SpCas9 has a known tolerance for mismatches.

- Solution: Switch to high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) or alternative Cas nucleases with inherently higher specificity (e.g., Cas12a) [3].

- Promiscuous sgRNA: The sgRNA has high similarity to multiple genomic sites.

Detection and Analysis Protocol:

- Prediction: Use tools like CRISPOR to identify potential off-target sites during the gRNA design phase [3].

- Targeted Detection: For candidate site sequencing, design primers flanking the top predicted off-target loci and sequence them after editing. For a more comprehensive profile, use methods like GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq [3].

- Comprehensive Analysis: Use whole genome sequencing (WGS) for the most thorough, unbiased detection of off-target edits and chromosomal aberrations [3].

Issue 3: Unintended On-Target Structural Variations

As discussed in the FAQs, Cas9 cutting can lead to large, unintended on-target mutations that are difficult to detect with standard methods [1].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inhibition of Canonical NHEJ: Using DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) to enhance HDR efficiency can dramatically increase the frequency of kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [1].

- Solution: Avoid or carefully titrate NHEJ-inhibiting compounds. Explore alternative HDR-enhancing strategies that do not disrupt core NHEJ factors, such as transient 53BP1 inhibition, which has not been associated with increased translocation frequencies in some studies [1].

- Standard Amplicon Sequencing: Typical analysis methods that use short-read sequencing and PCR amplification fail to detect large deletions that span primer binding sites.

- Solution: Employ long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) or specialized assays like CAST-Seq (chromosomal translocation sequencing) and LAM-HTGTS that are designed to detect and quantify these large SVs [1].

- Inhibition of Canonical NHEJ: Using DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) to enhance HDR efficiency can dramatically increase the frequency of kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [1].

Detection Protocol:

- CAST-Seq: This method is highly effective for identifying and quantifying CRISPR-induced translocations and other complex rearrangements. It involves a targeted enrichment and NGS-based workflow specifically designed for SV detection, making it suitable for preclinical safety assessment [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions for optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 experiments.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants [3] | Engineered nucleases with reduced off-target activity. | Ideal for applications requiring high specificity; may have slightly reduced on-target efficiency. |

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) [3] | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and guide RNA for direct delivery. | Reduces off-target effects due to short activity window; improves editing efficiency in many cell types. |

| Stably Expressing Cas9 Cell Lines [5] | Cell lines with constitutive Cas9 expression. | Ensures consistent editing and improves experimental reproducibility; avoids transfection variability. |

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) [1] | Small molecules that inhibit NHEJ to enhance HDR rates. | Can cause severe genomic aberrations (large deletions, translocations); use with extreme caution. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) [2] | Engineered particles for efficient protein delivery to hard-to-transfect cells (e.g., neurons). | Enables editing in postmitotic cells; high transduction efficiency with minimal immunogenicity. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNAs [3] | Synthetic guides with modifications (e.g., 2'-O-Me, PS bonds) to improve stability and performance. | Increases editing efficiency and reduces off-target effects; essential for in vivo therapeutic applications. |

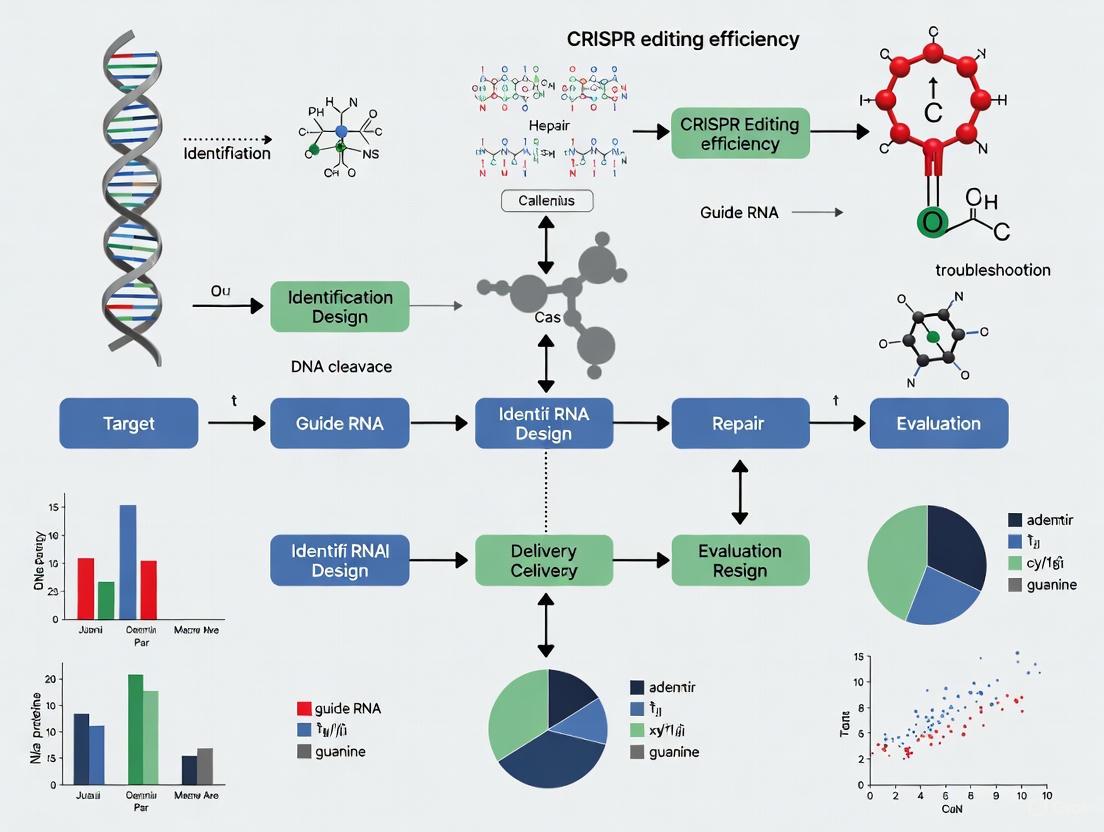

Visualizing the CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow and Repair Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9, from the creation of a double-strand break to the potential repair outcomes and associated technical challenges.

This troubleshooting guide provides a foundational framework for diagnosing and resolving common issues in CRISPR-Cas9 experiments. As the field evolves, staying informed on novel Cas variants, refined delivery methods, and advanced detection techniques will be crucial for achieving precise and efficient genome editing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common factors that lead to low editing efficiency in CRISPR experiments?

Low editing efficiency is most commonly caused by suboptimal guide RNA (gRNA) design, inefficient delivery methods, and low expression or activity of the Cas nuclease. The design of the gRNA is paramount; guides must be highly specific to the target and avoid off-target sites. Delivery is another critical bottleneck—whether using viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, or electroporation, the CRISPR machinery must efficiently reach the cell nucleus. Furthermore, the choice of promoter driving Cas9 and gRNA expression must be suitable for your specific cell type to ensure adequate levels of the nuclease and its guide [4] [6].

Q2: How can I improve the specificity of my edits and reduce off-target effects?

To enhance specificity and minimize off-target effects, researchers should:

- Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants that have been engineered for greater precision.

- Employ modified, chemically synthesized guide RNAs, which are more stable and can elicit a lower immune response, improving editing accuracy.

- Utilize ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for delivery. Delivering pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA complexes leads to a faster, more short-lived editing window, reducing the opportunity for off-target cuts [4] [6].

- Apply anti-CRISPR proteins. A newly developed system uses a cell-permeable protein to rapidly deactivate Cas9 after editing is complete, significantly reducing off-target activity [7].

Q3: My edits are successful but inconsistent, resulting in a mix of edited and unedited cells (mosaicism). How can I address this?

Mosaicism often arises from the timing of delivery and the cell cycle stage. To achieve a more homogeneous edited population:

- Synchronize your cell population to ensure delivery occurs at the optimal cell cycle stage for your desired repair pathway (e.g., S/G2 phases for homology-directed repair).

- Use inducible Cas9 systems to control the timing of nuclease activity.

- Isolate single-cell clones after editing. Following the editing process, perform single-cell dilution cloning and screen the resulting colonies to isolate clonal populations with uniform edits [4].

Q4: Are there new delivery technologies that can boost editing efficiency?

Yes, delivery technology is a rapidly advancing area. A significant recent development is the lipid nanoparticle spherical nucleic acid (LNP-SNA). This nanostructure wraps the CRISPR machinery in a protective, DNA-coated shell that cells absorb much more efficiently. In lab tests, this system tripled gene-editing success rates and improved precision compared to standard lipid nanoparticles [8]. Furthermore, researchers are continuously engineering new biodegradable ionizable lipids for LNPs that improve mRNA delivery to target organs like the liver, which is a common target for CRISPR therapies [9].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

The table below summarizes common issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency [4] [6] | Poor gRNA design, low transfection efficiency, suboptimal Cas9/gRNA expression. | Test 2-3 gRNAs; optimize delivery method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection); use RNPs; verify promoter suitability and codon-optimize Cas9. |

| High Off-Target Effects [4] [7] | Cas9 activity lingering in cells, gRNA homology with other genomic sites. | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants; design specific gRNAs with prediction tools; employ anti-CRISPR shut-off systems; deliver via RNP complexes. |

| Cell Toxicity [4] | High concentrations of CRISPR components. | Titrate component concentrations (start low); use RNPs or modified gRNAs to reduce immune stimulation. |

| Mosaicism [4] | Editing occurring at different cell cycles, delayed Cas9 expression. | Synchronize cell population; use inducible Cas9 systems; perform single-cell cloning post-editing. |

| Inability to Detect Edits [4] | Insensitive genotyping methods. | Use robust detection methods (T7EI assay, Surveyor assay, Sanger sequencing, or NGS). |

| Unsuccessful Cloning of gRNA [10] | Incorrectly designed oligonucleotides, degraded ds oligonucleotides. | Verify oligo design includes required cloning sequences (e.g., GTTTT, CGGTG); avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of oligonucleotides. |

Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Optimization

Protocol 1: Testing and Validating Guide RNA Efficiency

A critical first step is empirically determining the most effective gRNA for your target.

- Design: Select 2-3 bioinformatically predicted gRNAs for your target gene using reputable design tools [6] [11].

- Delivery: Transferd your chosen gRNAs and Cas9 (as plasmid, mRNA, or RNP) into your target cells. Include a positive control (a well-validated gRNA) and a negative control (a non-targeting gRNA) [4].

- Incubation: Allow 48-72 hours for editing to occur.

- Analysis: Extract genomic DNA. Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze the products using one of the following methods:

- Enzymatic Mismatch Assay: Use T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) or Surveyor assay on the PCR products. Cleaved bands indicate successful editing. Analyze by gel electrophoresis [4] [6].

- Sequencing: For the most accurate results, subject the PCR products to Sanger or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). This reveals the exact sequences and spectrum of indels [6].

Protocol 2: Delivering CRISPR Components as Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs)

RNP delivery can increase efficiency and reduce off-target effects.

- Complex Formation: In vitro, complex purified Cas9 protein with your synthesized, modified gRNA at a molar ratio of 1:2 to 1:3 (Cas9:gRNA). Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form the RNP complex [6].

- Cell Delivery: Deliver the pre-formed RNP complexes into your cells using a method suitable for your cell type, such as electroporation or lipofection (e.g., using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent) [10] [6].

- Advantages: This method leads to rapid editing, reduces the risk of immune activation and genomic integration of DNA, and shortens the window for Cas9 activity, thereby lowering off-target effects [6].

Key Factors and Optimization Workflow

The diagram below outlines the logical relationship between key factors, common issues, and optimization strategies in a CRISPR experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below details key reagents and their functions for successful and efficient CRISPR genome editing.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered versions of Cas9 with reduced off-target effects, crucial for therapeutic applications [4]. |

| Modified Synthetic gRNAs | Chemically synthesized guide RNAs with modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) that enhance stability, improve editing efficiency, and reduce immune response compared to in vitro transcribed (IVT) gRNAs [6]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and gRNA. The preferred delivery method for many applications due to high efficiency, rapid action, and reduced off-target effects [6]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A non-viral delivery vehicle, ideal for in vivo delivery. Recent advances include LNP-SNAs (Spherical Nucleic Acids), which dramatically improve cellular uptake and editing efficiency [8] [9]. |

| Anti-CRISPR Proteins (e.g., LFN-Acr/PA) | Proteins used to precisely "turn off" Cas9 activity after editing is complete. This new technology minimizes the time Cas9 is active in the cell, greatly reducing off-target effects [7]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) / Surveyor Assay Kits | Enzymatic mismatch detection kits used for initial, rapid assessment of editing efficiency at the target site by detecting DNA heteroduplexes [4] [6]. |

Advanced Strategies: Signaling and Workflow for Precision

For advanced applications requiring high precision, such as homology-directed repair (HDR), the cellular signaling pathways and experimental workflow become critical. The following diagram illustrates a strategy that combines optimal delivery with a safety switch to maximize on-target editing.

The efficiency and outcome of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing are profoundly influenced by the physiological state of the target cell. Recent research reveals that fundamentally different DNA repair mechanisms operate in dividing versus non-dividing (postmitotic) cells, leading to dramatic variations in editing results [2]. This cellular context dependency presents both significant challenges and opportunities for therapeutic genome editing, particularly for diseases affecting non-dividing tissues such as neurons and cardiomyocytes [2] [12].

Understanding these differences is crucial for troubleshooting low CRISPR editing efficiency. While dividing cells like immortalized cell lines (HEK293, HeLa) efficiently utilize certain repair pathways, therapeutically relevant primary cells and differentiated cells often exhibit slower editing kinetics and distinct repair outcomes [13] [2]. This technical guide provides troubleshooting strategies and FAQs to help researchers navigate these complexities and optimize editing protocols for their specific experimental systems.

Key Biological Differences: Why Cell Type Matters

DNA Repair Pathway Utilization

The core challenge stems from differential activation of DNA repair pathways across cell states. Dividing cells actively cycle through cell cycle phases, enabling them to utilize a broader repertoire of repair mechanisms, including homology-directed repair (HDR) and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) [2]. In contrast, non-dividing cells predominantly rely on non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and exhibit upregulated non-canonical DNA repair factors [2] [12].

Table 1: DNA Repair Pathway Activity in Different Cell States

| DNA Repair Pathway | Dividing Cells | Non-Dividing Cells | Cell Cycle Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) | High | Very High | No |

| Homology-directed repair (HDR) | High | Very Low | Yes (S/G2 phases) |

| Microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) | High | Low | Yes (S/G2 phases) |

| Alternative end joining | Variable | upregulated in neurons [2] | No |

Editing Kinetics and Outcome Distributions

The timeline for achieving maximal editing efficiency varies dramatically between cell types. In dividing cells, CRISPR-induced indels typically plateau within 1-2 days post-transfection. However, in non-dividing cells such as neurons and cardiomyocytes, indel accumulation can continue increasing for up to 2 weeks after Cas9 delivery [2]. This prolonged timeline reflects fundamental differences in how these cell types manage DNA damage response.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes Between Cell Types

| Editing Parameter | iPSCs (Dividing) | Neurons (Non-dividing) | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to maximal indel accumulation | 1-2 days | 14-16 days [2] | VLP delivery of Cas9 RNP to isogenic cells |

| Predominant repair pathway | MMEJ | NHEJ [2] | Sequencing of editing outcomes at multiple loci |

| Distribution of outcomes | Broad range of indels | Narrow distribution [2] | Deep sequencing analysis |

| Insertion-to-deletion ratio | Lower | Significantly higher [2] | Analysis of multiple sgRNAs |

Diagram Title: Differential CRISPR Repair in Dividing vs. Non-Dividing Cells

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my editing efficiency so low in primary neurons and cardiomyocytes?

Cause: Non-dividing cells exhibit inherently slower editing kinetics and limited repair pathway availability compared to immortalized cell lines [2].

Solutions:

- Extend your assessment timeline: Allow at least 2 weeks post-transduction before evaluating editing outcomes in non-dividing cells [2].

- Optimize delivery methods: Use virus-like particles (VLPs) pseudotyped with VSVG and BaEVRless (BRL) glycoproteins, which achieve >95% transduction efficiency in human neurons [2].

- Manipulate DNA repair pathways: Apply chemical or genetic perturbations to direct repair toward desired outcomes in non-dividing cells [2] [12].

FAQ 2: Why do I see different mutation patterns in my stem cells versus differentiated cells?

Cause: Genetically identical cells at different differentiation stages employ distinct DNA repair machinery, resulting in divergent editing outcomes [2].

Solutions:

- Pre-validate sgRNAs in your target cell type: sgRNA performance varies significantly between cell types, even when targeting the same genomic locus [13] [11].

- Select target loci carefully: For knockout experiments in cells with multiple isoforms, design sgRNAs targeting exons common to all relevant isoforms [13].

- Anticipate pathway-specific outcomes: Recognize that MMEJ-associated larger deletions predominate in dividing cells, while NHEJ-associated small indels are more common in non-dividing cells [2].

FAQ 3: How can I improve editing precision in non-dividing cells for therapeutic applications?

Cause: The natural repair pathway bias in non-dividing cells favors error-prone NHEJ over precise HDR [2] [14].

Solutions:

- Consider alternative editors: Base editors or prime editors can achieve precise modifications without requiring DSBs or HDR, working efficiently in non-dividing cells [2].

- Modulate repair pathways: Chemical inhibition of NHEJ factors or activation of alternative repair pathways can shift outcome distributions [2] [12].

- Use RNP complexes: Preassembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes often show higher editing efficiency and specificity than plasmid-based delivery, especially when delivered via electroporation or nanoparticles [15] [16].

Essential Protocols for Cell-Type Specific Editing

Protocol: Rapid Assessment of Editing Outcomes Using Fluorescent Reporters

This protocol enables high-throughput screening of editing efficiency across different cell types using an eGFP to BFP conversion assay [14].

Materials:

- eGFP-positive cell lines (e.g., HEK293T, Hepa 1-6, IMR90, HepG2)

- SpCas9-NLS protein

- sgRNA targeting eGFP locus: GCUGAAGCACUGCACGCCGU

- Optimized BFP mutation HDR template

- Delivery reagent (Polyethylenimine or ProDeliverIN CRISPR)

- Flow cytometer with appropriate filters

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Cell Preparation: Culture eGFP-positive cells to 70-80% confluency in appropriate complete medium [14].

- RNP Complex Formation: Combine SpCas9 protein with sgRNA at molar ratio 1:1.2 and incubate 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Transfection: Deliver RNP complexes with or without HDR template using your preferred method. For HEK293T cells, polyethylenimine (PEI) provides efficient delivery.

- Incubation: Maintain cells for 3-7 days post-transfection to allow editing and fluorescence conversion.

- Analysis: Analyze cells by flow cytometry, measuring eGFP loss (NHEJ) and BFP gain (HDR) to quantify editing outcomes.

Diagram Title: Fluorescent Reporter Workflow for Editing Assessment

Protocol: Optimizing Delivery for Challenging Non-Dividing Cells

Efficient delivery remains a primary challenge in non-dividing cells. This protocol outlines VLP-based delivery optimized for neurons and cardiomyocytes [2].

Materials:

- HIV-based or FMLV-based VLP systems

- VSVG and BaEVRless (BRL) pseudotyping proteins

- Cas9 RNP complexes

- iPSC-derived neurons or cardiomyocytes

- Appropriate neuronal or cardiac culture media

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- VLP Production: Produce VLPs containing Cas9 RNP using appropriate packaging cells and pseudotyping with VSVG/BRL glycoproteins [2].

- Cell Preparation: Differentiate iPSCs to target cell type (neurons/cardiomyocytes), confirming purity (>95% NeuN+ for neurons) and postmitotic state (Ki67-negative) [2].

- Transduction: Apply VLPs to cells at optimized MOI, determined through pilot experiments.

- Extended Incubation: Maintain cells for 14-16 days post-transduction, refreshing media as needed.

- Outcome Assessment: Harvest cells at multiple timepoints and analyze editing outcomes using next-generation sequencing to capture the prolonged editing kinetics.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Cell-Type Specific Editing

Table 3: Key Reagents for Optimizing CRISPR Across Cell Types

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery Systems | Virus-like particles (VLPs) pseudotyped with VSVG/BRL [2] | Efficient Cas9 RNP delivery to non-dividing cells | Achieves >95% transduction in human neurons |

| Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [16] | Non-viral RNP delivery for in vivo applications | Tissue-specific targeting possible | |

| Editing Cargo | Preassembled RNP complexes [15] [16] | Highest editing efficiency with minimal off-target effects | Ideal for sensitive primary cells |

| High-fidelity Cas9 variants [15] | Reduced off-target effects | Important for therapeutic applications | |

| Reporter Systems | eGFP-BFP conversion system [14] | Rapid quantification of HDR vs NHEJ outcomes | Enables high-throughput optimization |

| Cell Models | iPSC-derived neurons & cardiomyocytes [2] | Physiologically relevant non-dividing models | Genetically matched to iPSC controls available |

The dramatic differences in CRISPR repair outcomes between dividing and non-dividing cells underscore the critical importance of cell-type specific optimization in genome editing experiments. By understanding the distinct DNA repair environments in these cells, researchers can develop more effective troubleshooting strategies and design better experiments.

Future directions in this field include developing small molecule modulators of cell-type specific repair factors, engineering novel Cas variants with reduced dependence on endogenous repair pathways, and optimizing delivery platforms that account for the unique biology of non-dividing cells. As CRISPR-based therapeutics advance toward clinical applications, acknowledging and addressing these fundamental cellular differences will be essential for success, particularly for neurological and cardiac diseases where non-dividing cells are the primary therapeutic targets.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) dominate over homology-directed repair (HDR) in postmitotic cells like neurons?

A1: The dominance of NHEJ in postmitotic cells is fundamentally due to cell cycle restrictions. HDR is strictly confined to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle because it requires a sister chromatid as a template for repair [2] [17]. Postmitotic cells, such as mature neurons and cardiomyocytes, have permanently exited the cell cycle. Consequently, they lack this essential template and cannot activate the HDR machinery effectively [18] [17]. In contrast, NHEJ is active throughout all cell cycle phases and does not require a template, making it the primary and most readily available pathway for repairing double-strand breaks in non-dividing cells [17].

Q2: We are observing very low CRISPR knockout efficiency in our primary neuronal cultures. Is this a delivery problem or a repair problem?

A2: While efficient delivery is always a consideration, recent evidence strongly suggests that the inherently slow kinetics of DNA repair in postmitotic cells is a major contributing factor. Research shows that while indels in dividing cells plateau within days, they can continue to accumulate in neurons for up to two weeks after Cas9 delivery [2] [19]. Before troubleshooting delivery, ensure you are allowing a sufficiently long time for editing outcomes to manifest. Furthermore, confirm that your experimental system is truly postmitotic, as the DNA repair pathway balance differs significantly between dividing and non-dividing cells [2].

Q3: Are the risks of large structural variations (like chromosomal translocations) different when editing postmitotic cells?

A3: The risk of structural variations (SVs) is a critical safety concern for all CRISPR therapies. While the unique repair environment of postmitotic cells may influence SV profiles, the use of certain NHEJ-inhibiting small molecules to enhance HDR in other cell types has been shown to drastically increase the frequency of kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [1]. This underscores the importance of using advanced sequencing methods (e.g., CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS) that can detect these large aberrations, as they are often missed by standard short-read amplicon sequencing [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Knock-in Efficiency via HDR

Problem: Failure to achieve precise gene insertion or correction via HDR in postmitotic cells.

Solution: Given the near impossibility of performing standard HDR in non-cycling cells, consider switching to alternative precision editing tools that do not rely on the HDR pathway.

- Utilize Advanced Editors: Consider Prime Editing or Base Editing systems. These technologies can mediate precise changes without requiring a double-strand break or a donor template, making them much more effective in postmitotic cells. For example, prime editing has been used successfully in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes to correct disease-causing mutations with up to 34.8% efficiency [20].

- Explore Novel Nuclease Platforms: Investigate platforms like ARCUS nucleases, which have been reported to trigger high-frequency homologous recombination and achieve precise edits in non-dividing cells [20].

- If HDR is Absolutely Necessary: If you must use HDR, strategies involve artificially manipulating the cell cycle or DNA repair pathways, but this is typically only feasible in ex vivo settings with dividing cells. For postmitotic cells, HDR remains a major challenge, and alternative editors are strongly recommended [18] [17].

Key Data and Experimental Comparisons

The tables below summarize core quantitative findings and methodological details from recent key studies.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Repair Kinetics and Outcomes in Dividing vs. Postmitotic Cells

| Feature | Dividing Cells (e.g., iPSCs) | Postmitotic Cells (e.g., Neurons) | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Repair Pathway | Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) & NHEJ | Classical Non-Homologous End Joining (cNHEJ) | [2] |

| HDR Efficiency | Low, but possible in S/G2 phase | Extremely Low / Theoretically impossible | [18] [17] |

| Time to Indel Plateau | A few days | Up to 2 weeks | [2] [19] |

| Indel Distribution | Broad, larger deletions (MMEJ-like) | Narrow, small indels (NHEJ-like) | [2] |

| Therapeutic Example | Ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem cells | Gene inactivation for dominant neurodegenerative diseases | [2] [21] |

Table 2: Small Molecules for Modulating CRISPR Editing Efficiency

| Small Molecule | Target | Effect on Editing | Reported Efficiency Increase | Notes and Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repsox | TGF-β pathway (SMAD2/3/4) | Enhances NHEJ-mediated knockout | Up to 3.16-fold (in porcine cells) | Mechanism involves downregulation of SMAD proteins [22]. |

| AZD7648 | DNA-PKcs (NHEJ) | Inhibits NHEJ to enhance HDR | N/A (HDR increase reported) | Risks: Significantly increases large structural variations and chromosomal translocations [1]. |

| Various Inhibitors | 53BP1, Ligase IV | Inhibits NHEJ to enhance HDR | Varies | Transient 53BP1 inhibition did not increase translocations in one study, but general suppression of NHEJ carries risks [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing DNA Repair in Postmitotic Neurons

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 Nature Communications study that directly compared repair outcomes in iPSCs and iPSC-derived neurons [2].

Workflow Title: Comparing CRISPR Repair in Dividing and Postmitotic Cells

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Cell Line Preparation:

Validation of Postmitotic State:

CRISPR Delivery via Virus-Like Particles (VLPs):

- Rationale: Standard transfection is inefficient in neurons. VLPs engineered from Friend murine leukemia virus (FMLV) or HIV, pseudotyped with VSVG/BRL glycoproteins, can achieve >95% transduction efficiency in human neurons [2].

- Procedure: Produce VLPs loaded with pre-assembled Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexed with your target sgRNA.

Transduction and Time-Course Experiment:

Analysis of Editing Outcomes:

- Amplify the target genomic locus by PCR and perform next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Use computational tools (e.g., CRISPResso2) to quantify the spectrum and frequency of insertion/deletion mutations (indels).

- Key Analysis: Compare the kinetics of indel accumulation and the distribution of indel types (e.g., ratio of small vs. large deletions) between the two cell types [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying DNA Repair in Postmitotic Cells

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Postmitotic Cells |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-Derived Neurons | Provides a genetically defined, human-relevant model of postmitotic cells. | Essential for creating isogenic pairs with dividing iPSCs to isolate cell cycle effects on DNA repair [2]. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Efficient delivery of Cas9 protein (as RNP) into hard-to-transfect cells. | Superior to plasmids for transient, efficient Cas9 delivery to neurons, minimizing off-target effects from prolonged expression [2] [19]. |

| NHEJ-Enhancing Molecules (e.g., Repsox) | Small molecules that inhibit specific pathways to bias repair toward NHEJ. | Can boost NHEJ-mediated knockout efficiency in challenging cell types, as demonstrated in porcine cells [22]. |

| Prime Editing System (e.g., PE4) | A "search-and-replace" system that directly writes new genetic information without DSBs. | Enables precise single-base changes or small insertions/deletions in postmitotic cells where HDR is ineffective [20]. |

| Advanced Sequencing (CAST-Seq) | Detects large structural variations and chromosomal translocations. | Critical for comprehensive safety profiling, as standard amplicon-seq misses large deletions from CRISPR editing [1]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q: Why does CRISPR-induced indel formation happen so slowly in my postmitotic cells, such as neurons and cardiomyocytes, compared to standard dividing cell lines?

A: Slow accumulation of insertions and deletions (indels) is a fundamental characteristic of how non-dividing cells respond to CRISPR-Cas9-induced DNA damage. Unlike rapidly proliferating cells, which resolve double-strand breaks (DSBs) quickly to avoid cell death during division, postmitotic cells lack this pressure and repair DNA over a much longer, weeks-long timeline [2]. The primary cause is the different DNA repair pathway preferences: dividing cells frequently use faster, more mutagenic pathways like microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), while neurons rely more heavily on the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which can proceed at a slower pace and even result in a higher ratio of small insertions to deletions [2].

Key Differences in DNA Repair Between Dividing and Non-Dividing Cells

| Feature | Dividing Cells (e.g., iPSCs) | Non-Dividing Cells (e.g., Neurons, Cardiomyocytes) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary DSB Repair Pathway | MMEJ-like (larger deletions predominant) [2] | NHEJ-like (smaller indels predominant) [2] |

| Typical Indel Accumulation Timeline | Plateaus within a few days [2] | Continues to increase for up to 16 days or more [2] |

| Ratio of Insertions to Deletions | Lower [2] | Significantly higher [2] |

| Pressure for Fast Repair | High (to pass cell cycle checkpoints) [2] | Low (no replication checkpoints) [2] |

Q: What experimental evidence supports this prolonged editing timeline in neurons?

A: A key 2025 study used virus-like particles (VLPs) to deliver Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) to both human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and genetically identical iPSC-derived neurons [2]. The researchers tracked the formation of indels over time and found that while editing in iPSCs reached a maximum within a few days, indels in neurons continued to accumulate for at least two weeks post-delivery [2]. This same prolonged timeline was also observed in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, confirming it is a trait of postmitotic cells [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Tracking Indel Kinetics

- Cell Models: Human iPSCs and iPSC-derived cortical-like excitatory neurons (confirmed postmitotic by Ki67-negative and NeuN-positive staining) [2].

- CRISPR Delivery: Cas9 RNP delivered via VSVG-pseudotyped or VSVG/BRL-co-pseudotyped Virus-Like Particles (VLPs), achieving up to 97% transduction efficiency [2].

- Time-Course Experiment:

- Transduce cells with Cas9 VLPs.

- Harvest cells at multiple time points post-transduction (e.g., days 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, 16).

- Extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify the target genomic region by PCR and perform next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPResso2) to quantify the percentage of reads containing indels at each time point [2].

- Validation: The extended timeline was replicated using multiple sgRNAs and two different VLP platforms, ruling out delivery delays as the sole cause [2].

Diagram 1: Divergent CRISPR repair timelines in dividing and non-dividing cells.

Q: How can I troubleshoot and potentially improve editing efficiency in these challenging cell types?

A: While the slow timeline may be intrinsic, you can optimize your experiment for the best possible outcome.

- Optimize Delivery: Ensure your CRISPR components are efficiently delivered. VLPs pseudotyped with VSVG and BaEVRless (BRL) have shown high efficiency (up to 97%) in human neurons [2]. For other non-dividing cells like resting T cells, electroporation of Cas9 RNP can be effective [2] [5].

- Validate sgRNA Activity: A poorly designed sgRNA is a common cause of low efficiency [4] [5]. Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling) to design highly specific sgRNAs with optimal GC content (40-60%) and test 3-5 different sgRNAs per gene to identify the most effective one [5] [23].

- Confirm Successful Transduction and Cutting: Use immunocytochemistry to confirm the presence of Cas9-induced DSBs by co-staining for markers like γH2AX and 53BP1 in your target cells [2].

- Allow Sufficient Time for Editing: Plan your experiment with the extended timeline in mind. Harvesting cells too early (e.g., before 7 days) will capture only a fraction of the eventual indels. Monitor editing over a 2-week period to capture the full effect [2].

- Consider Alternative Editors: If precise nucleotide change is the goal, base editing or prime editing might be more efficient than Cas9 nuclease in neurons, as they do not rely on the formation of a DSB and can sometimes show comparable or even higher efficiency within a shorter time frame [2].

Q: Are there specific reagents or tools that can help study this phenomenon?

A: Yes, the table below lists key reagents and tools used in the foundational research on this topic.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Protein-based delivery of Cas9 RNP to hard-to-transfect postmitotic cells [2]. | VSVG-pseudotyped HIV VLPs or VSVG/BRL-co-pseudotyped FMLV VLPs [2]. |

| iPSC-Derived Neurons | A genetically defined, clinically relevant model for studying DNA repair in human neurons [2]. | Cortical-like excitatory neurons; >95% NeuN-positive, >99% Ki67-negative [2]. |

| Cas9 RNP Complex | The active editing complex; direct delivery of RNP reduces off-target effects and allows for transient activity [2]. | Pre-complexed purified Cas9 protein and sgRNA [2]. |

| sgRNA Design Tools | Bioinformatics software to predict and select high-activity, specific guide RNAs [5]. | CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling, GuideScan [5] [23]. |

| Antibodies for ICC | Validate DSB formation and repair protein recruitment [2]. | Anti-γH2AX and anti-53BP1 [2]. |

Diagram 2: A logical troubleshooting workflow for slow indel accumulation.

Strategic Guide and Donor Design for Knockout and Knock-in Experiments

FAQ: Addressing Key Challenges in sgRNA Design and Workflow

What are the most critical factors for designing an sgRNA for gene knockout? The primary factors are on-target activity and minimizing off-target effects. Successful design depends on:

- sgRNA Sequence: The nucleotide sequence at specific positions in the guide region significantly influences efficiency. For example, certain bases in the "seed" region (positions 1-10) and the non-seed region (positions 15-18) are critical [24].

- GC Content: Optimal GC content (typically 40-60%) improves stability and binding.

- Off-target Potential: The sgRNA should have minimal similarity to other genomic sequences, especially in the seed region, to prevent unintended cuts [5] [25].

- Target Location: For knockouts, target an exon near the 5' end of the gene's coding sequence to maximize the chance of a frameshift mutation [5].

Why is my homology-directed repair (HDR) efficiency so low, and how can I improve it? HDR is inherently less efficient than error-prone repair pathways like non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) in mammalian cells [26] [18]. You can improve HDR by:

- Modulating DNA Repair Pathways: Inhibiting key NHEJ factors (e.g., KU70, KU80, LIG4) or activating HDR factors (e.g., CDK1, CtIP) can shift the balance toward HDR. One study showed that simultaneously activating CDK1 and repressing KU80 increased HDR rates by an order of magnitude [26].

- Using High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Enzymes like HiFi Cas9 can reduce off-target effects, but be aware that some can cause a guide-dependent loss of on-target efficiency [24].

- Cell Cycle Timing: HDR is most active in the S and G2 phases. Transfecting cells during these phases or using cell cycle synchronization can enhance HDR [26].

Important Safety Note: Strategies that inhibit the NHEJ pathway (e.g., using DNA-PKcs inhibitors) to enhance HDR can carry a hidden risk. They have been shown to significantly increase the frequency of large, on-target structural variations, including megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations, which traditional short-read sequencing often misses [27].

My knockout worked in one cell line but not another. What could be the reason? Cell line specificity is a major challenge in CRISPR experiments. Causes for variable efficiency include:

- DNA Repair Machinery: Different cell lines have varying levels of DNA repair enzymes. Some, like HeLa cells, have highly efficient repair systems that can quickly fix Cas9-induced breaks, reducing knockout success [5].

- Cell State: Post-mitotic cells, such as neurons, repair DNA with unique kinetics and favor different repair pathways (like NHEJ over MMEJ) compared to dividing cells, leading to a narrower range of edits and an extended editing window [28].

- Transfection Efficiency: Delivery of CRISPR components can vary dramatically between cell types. Hard-to-transfect cells may require optimized methods like electroporation or the use of stable Cas9-expressing cell lines [5].

How many sgRNAs should I test per gene? It is strongly recommended to test multiple sgRNAs per gene, typically 3 to 5 [5]. This is because sgRNA efficiency is highly variable and sequence-dependent. Testing multiple guides ensures that at least one will be highly effective, safeguarding your experiment against the failure of a single sgRNA.

Optimized sgRNA Design Parameters

The table below summarizes key design rules for maximizing on-target activity and specificity, synthesized from large-scale empirical studies [25].

Table 1: Key sgRNA Sequence Features for Optimal On-Target Activity

| Feature | Optimal Characteristic | Rationale & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Region (pos 1-10) | Specific nucleotide preferences (e.g., G at pos 1, C at pos 19 for some variants) | Critical for initial DNA binding; specific bases are enriched in highly active guides [25] [24]. |

| Non-Seed Region (pos 15-18) | Avoid sequences leading to loss of efficiency in high-fidelity Cas9 variants [24]. | Interacts with the REC3 domain of Cas9; mutations in high-fidelity variants can make efficiency dependent on these positions. |

| GC Content | 40% - 60% | Guides with very high or very low GC content can form stable secondary structures or have poor binding affinity [5]. |

| Off-target Score | Select sgRNAs with the lowest predicted off-target activity. | Minimizes unintended genomic alterations. Tools like MOFF score can predict off-target potential [25] [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Validating sgRNA Efficiency and Knockout

This protocol outlines a robust method for generating and validating knockout hPSC lines using an inducible Cas9 system, incorporating optimizations for high efficiency [29].

Design and Synthesis:

- Design 3-5 sgRNAs per target gene using a reliable algorithm (e.g., Benchling, CCTop, or GuideVar for high-fidelity Cas9 variants) [29] [24].

- Synthesize chemically modified sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNA) with 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both ends to enhance stability within cells, which has been shown to improve editing rates [29].

Cell Preparation and Nucleofection:

- Culture your engineered cell line (e.g., hPSCs with doxycycline-inducible Cas9).

- Induce Cas9 expression with doxycycline 24 hours before nucleofection.

- Dissociate cells and electroporate using a high-efficiency program (e.g., program CA137 on a Lonza 4D-Nucleofector). A critical optimized parameter is using 5 µg of sgRNA for 8×10^5 cells [29].

- For difficult targets, a second nucleofection with the same sgRNA can be performed 3 days after the first to boost indel rates.

Assessing Editing Efficiency (INDELs):

- Harvest cells 3-5 days post-nucleofection and extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify the target region by PCR and submit the product for Sanger sequencing.

- Analyze the sequencing chromatograms using algorithms like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) or TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) to quantify the percentage of insertions and deletions (INDELs) [29]. This optimized system can achieve INDEL rates of 82-93% [29].

Functional Validation of Knockout:

- Perform Western blotting to confirm the absence of the target protein. This is a crucial step, as high INDEL percentages do not always equate to complete protein loss. Some reading frame shifts may not be disruptive, resulting in "ineffective sgRNAs" and retained protein expression [29].

- For further phenotypic characterization, you can perform downstream assays like flow cytometry, reporter assays, or functional cellular assays specific to your target [5].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for sgRNA validation and knockout confirmation.

Advanced Strategy: Enhancing HDR with CRISPRa/i

For precise editing requiring HDR, a powerful strategy is to use catalytically dead guide RNAs (dgRNAs) to reprogram the cell's DNA repair machinery at the transcriptional level. This method uses a single active Cas9 for cutting and dgRNAs for regulation [26].

Diagram 2: CRISPRa/i mechanism for HDR enhancement.

Workflow:

- Co-deliver three components into your cells:

- A plasmid expressing active Cas9 and a target-specific sgRNA to create the DSB.

- Plasmids expressing dgRNAs that recruit activator complexes (like MS2-P65-HSF1) to promoters of HDR-related genes (e.g., CDK1, CtIP).

- Plasmids expressing dgRNAs that recruit repressor complexes (like COM-KRAB) to promoters of NHEJ-related genes (e.g., KU70, KU80, LIG4) [26].

- The dgRNAs activate HDR pathway components and repress NHEJ components, steering the repair of the Cas9-induced break toward the precise HDR pathway.

- This synergistic approach has been shown to increase HDR efficiency by up to 15-fold compared to standard methods [26].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for CRISPR sgRNA Design and Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example & Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | Algorithms to predict sgRNA on-target efficiency and off-target effects. | Benchling was identified as providing the most accurate predictions in one study [29]. GuideVar is a framework specifically for predicting performance with high-fidelity Cas9 variants [24]. |

| Stable Cas9 Cell Lines | Cell lines engineered for consistent Cas9 nuclease expression. | Eliminates variability from transient transfection, enhancing reproducibility and knockout efficiency (e.g., hPSCs-iCas9) [5] [29]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced off-target activity. | HiFi Cas9 and LZ3 are promising variants, but their efficiency can be sgRNA-sequence-dependent [24]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Synthetic sgRNAs with altered backbone for increased nuclease resistance. | Enhances sgRNA stability within cells, leading to higher editing efficiency [29]. |

| Analysis Software | Tools to quantify editing outcomes from Sanger sequencing data. | ICE (Synthego) and TIDE are widely used to calculate INDEL percentages from mixed sequencing traces [29]. |

Within the broader context of troubleshooting low CRISPR editing efficiency, selecting the appropriate Cas protein is a critical first step. The choice between wild-type, high-fidelity, and newly engineered variants directly impacts the success of your experiments, influencing on-target activity, off-target rates, and compatibility with your delivery system. This guide provides targeted FAQs and troubleshooting advice to help you navigate this complex decision.

FAQs: Cas Protein Selection

Q1: What are the primary limitations of wild-type SpCas9 that would lead me to consider an alternative?

Wild-type Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), while a workhorse, has three key limitations that can cause low experimental efficiency or confounding results:

- Off-target effects: Its complementarity requirements are not very stringent, allowing it to recognize and cleave non-specific DNA sequences with similar protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs), such as NAG or NGA, leading to unwanted mutations [30].

- Large size: At about 4.2 kb, the SpCas9 coding sequence is difficult to package into delivery vectors with limited cargo capacity, such as adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), hindering certain in vivo applications [30].

- Restrictive PAM requirement: The canonical NGG PAM sequence limits the genomic regions that can be targeted, reducing the flexibility of your experimental design [30].

Q2: When should I use a high-fidelity Cas9 variant?

High-fidelity variants are engineered to minimize off-target cleavage while retaining robust on-target activity. They are essential for applications where specificity is paramount.

- SpCas9-HF1 is an early high-fidelity variant that harbors four alanine substitutions (N497A, R661A, Q695A, Q926A) designed to reduce non-specific interactions with the DNA phosphate backbone [31]. GUIDE-seq experiments showed it rendered all or nearly all off-target events undetectable for standard non-repetitive target sites while maintaining comparable on-target activity for over 85% of sgRNAs tested [31].

- eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) is a more recently engineered high-fidelity nuclease that achieves exceptionally low off-target editing without the common trade-off of reduced on-target activity. It is derived from Parasutterella secunda Cas9 and is commercially available in both recombinant protein and mRNA formats [30].

Q3: I need to deliver CRISPR components via AAV. What are my best options?

For AAV delivery, compact Cas proteins are necessary. The table below summarizes key small-sized variants.

| Cas Protein | Origin | Size (amino acids) | PAM Sequence | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SaCas9 [30] | Staphylococcus aureus | 1053 | 3'-NNGRRT | Popular choice; used in neuronal studies, hepatitis B research, and plant genomes; has high-fidelity (SaCas9-HF) and broad-PAM (KKH-SaCas9) variants. |

| CjCas9 [30] | Campylobacter jejuni | ~984 | 3'-NNNNRYAC | Another naturally small Cas9 ortholog suitable for viral delivery. |

| hfCas12Max [30] | Engineered from Cas12i | 1080 | 5'-TN | High-fidelity nuclease; broader PAM recognition than SpCas9; uses a shorter crRNA. |

| Cas12g [32] | Type V-G System | 767 | None identified | RNA-guided ribonuclease (RNase) with collateral RNase and single-strand DNase activities; thermostable. |

Q4: Are there Cas variants that can target a wider range of genomic sequences?

Yes, several variants overcome the restrictive NGG PAM of SpCas9.

- ScCas9: Isolated from Streptococcus canis, it recognizes a less stringent 5′-NNG-3′ PAM, significantly expanding the potential target space [30].

- Cas12 Nucleases: Many Type V effectors, such as Cas12c, Cas12h, and Cas12i, recognize different PAM sequences. For instance, Cas12i prefers a 5'-TTN PAM [32].

- hfCas12Max: This engineered variant recognizes a simple 5'-TN PAM, enabling targeting of regions inaccessible to SpCas9 [30].

Q5: What is the role of AI in the future of Cas protein design?

Artificial intelligence is now being used to design novel Cas proteins that bypass the functional trade-offs of naturally derived systems. For example, OpenCRISPR-1 is an AI-generated gene editor. Its sequence is over 400 mutations away from any known natural Cas protein, yet it demonstrates comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being compatible with base editing. This approach can generate a massive expansion of functional diversity, creating editors with optimal properties for specific applications [33].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Editing Efficiency

Problem: Suspected Off-Target Effects

- Solution 1: Switch to a high-fidelity Cas variant like SpCas9-HF1 or eSpOT-ON. These are specifically engineered to minimize non-specific DNA cleavage [31] [30].

- Solution 2: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling) to design sgRNAs with maximal specificity. Predict and screen potential off-target sites for your sgRNA design [5].

- Solution 3: For wild-type SpCas9, consider using truncated sgRNAs with shortened complementarity regions, which can improve specificity [31].

Problem: Low On-Target Editing Efficiency

- Solution 1: Optimize sgRNA Design. Ensure your sgRNA has optimal GC content (typically 40-60%), avoids stable secondary structures, and is targeted to a genomically accessible region. Test 3-5 different sgRNAs for your target to identify the most effective one [5].

- Solution 2: Improve Delivery Efficiency. Low transfection efficiency means only a subset of cells receive the editing components.

- Chemical Transfection: Optimize lipid-based transfection reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine, DharmaFECT) for your specific cell type [5].

- Physical Methods: Use electroporation for hard-to-transfect cell lines [5] [4].

- Viral Delivery: For primary cells or in vivo work, use lentivirus or AAV (with a suitably small Cas protein like SaCas9) [30] [5].

- Solution 3: Use Stably Expressing Cas9 Cell Lines. Transient transfection can lead to variable expression levels. Using a validated, stable cell line that constitutively expresses Cas9 ensures consistent nuclease presence and can improve editing efficiency and reproducibility [5].

- Solution 4: Consider Cell Line Specificity. Be aware that different cell lines have varying DNA repair activity. Cell lines like HeLa with highly efficient DNA repair mechanisms can show reduced knockout efficiency. You may need to adjust protocols or model systems accordingly [5].

Problem: Difficulty with Viral Vector Packaging

- Solution: Select a compact Cas protein. The best-established option is SaCas9. Alternatively, explore newer small variants like hfCas12Max or Cas12g [30] [32].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Cas9 Fidelity with GUIDE-seq

The following detailed protocol is adapted from the validation of the SpCas9-HF1 variant [31].

1. Principle: Genome-wide unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq) detects double-strand breaks (DSBs) by capturing the integration of a transfected double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag. This allows for a genome-wide, unbiased profile of both on-target and off-target nuclease activity.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Human cells (e.g., HEK293T)

- Plasmids: Wild-type SpCas9 and high-fidelity variant (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) expression plasmids; sgRNA expression plasmid

- GUIDE-seq dsODN tag

- Transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000)

- Lysis buffer for genomic DNA extraction

- PCR reagents and primers for on-target and potential off-target sites

- Next-generation sequencing library preparation kit

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Co-transfect cells with the Cas9 expression plasmid, sgRNA plasmid, and the GUIDE-seq dsODN tag.

- Step 2: Incubate for 48-72 hours to allow for editing and tag integration.

- Step 3: Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA.

- Step 4: Verify on-target activity using a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay or T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay on the target site amplicon.

- Step 5: Perform GUIDE-seq library construction.

- Shear genomic DNA to an average fragment size of 500 bp.

- Prepare sequencing libraries using adapters. The GUIDE-seq dsODN tag is designed to serve as a primer binding site during PCR amplification, enriching for sequences that have incorporated the tag.

- Step 6: Sequence the libraries on a next-generation sequencing platform.

- Step 7: Bioinformatic Analysis. Map the sequenced reads to the reference genome and identify genomic locations where the dsODN tag has been integrated, indicating a DSB site.

4. Data Analysis:

- Compare the number and sequence of off-target sites identified for wild-type SpCas9 versus the high-fidelity variant.

- Confirm key off-target sites identified by GUIDE-seq using targeted deep sequencing of PCR amplicons from transfected cells that did not receive the dsODN tag.

Cas Protein Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for selecting the most appropriate Cas protein for your experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and reagents for working with Cas protein variants, as featured in the cited experiments.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpOT-ON) | Engineered nucleases for reducing off-target effects in sensitive applications like therapeutic development [31] [30]. |

| Compact Cas Proteins (e.g., SaCas9, hfCas12Max, CjCas9) | Small-sized nucleases enabling efficient delivery via size-limited vectors like AAVs [30]. |

| Stably Expressing Cas9 Cell Lines | Cell lines with consistent Cas9 expression, improving editing efficiency and reproducibility over transient transfection [5]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Non-viral delivery system for encapsulating and delivering CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) or mRNA in vivo [30]. |

| GUIDE-seq dsODN Tag | A double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide used to capture and sequence genome-wide double-strand breaks for comprehensive off-target profiling [31]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools (e.g., Benchling, CRISPR Design Tool) | Software for designing and optimizing highly specific sgRNA sequences and predicting potential off-target sites [5]. |

A key step of any CRISPR workflow is successfully delivering the guide RNA (gRNA) and Cas nuclease into your target cells. The choice of delivery system is frequently the primary variable determining the success or failure of an experiment. When editing efficiency is low, the delivery method is often the culprit. This guide provides a structured, troubleshooting-focused comparison of three primary delivery systems—plasmids, viral vectors, and ribonucleoprotein (RNP) electroporation—to help you diagnose problems and improve your results.

The questions and answers below are framed within the context of a broader thesis on troubleshooting low CRISPR editing efficiency, guiding you from problem identification to solution implementation.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My editing efficiency is low across multiple cell lines. What is the most common factor I should check first?

The most common factor is the format of the CRISPR components and their delivery method. Each format has a different cellular journey that impacts how quickly and efficiently editing occurs, which in turn affects off-target effects and cytotoxicity.

- Problem: Using a DNA-based format (plasmid or viral vector) that requires transcription and/or translation before editing can begin. This delays editing, increasing the window for off-target effects and cellular stress.

- Solution: Switch to a pre-complexed Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) format. The RNP complex is active immediately upon delivery and degrades quickly, leading to faster editing, higher efficiency, and reduced off-target effects [34] [35].

- Workflow: The diagram below illustrates the simplified, efficient pathway of RNP delivery compared to DNA-based methods.

FAQ 2: I need to edit hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells or iPSCs. Plasmids and lipofection are not working. What is a more effective strategy?

For sensitive and hard-to-transfect cells, RNP-based Electroporation, particularly Nucleofection, is the gold standard. Physical delivery methods outperform chemical ones for these cell types.

- Problem: Lipid-based transfection (lipofection) of plasmids or RNPs struggles to cross the membrane of difficult cells and can be cytotoxic. Plasmid delivery also requires nuclear entry, which is inefficient in non-dividing cells.

- Solution: Use electroporation to deliver pre-assembled RNPs. For highest efficiency in primary cells and stem cells, use Nucleofector systems, which are optimized for nuclear delivery [34] [35]. To further boost efficiency, consider adding electroporation enhancers, which are carrier molecules that improve RNP delivery and cell viability [35].

- Protocol: Optimized RNP Electroporation for Difficult Cells

- Complex Formation: Incubate purified Cas9 protein with synthetic gRNA at a molar ratio of 1:2 to 1:3 for 10-20 minutes at room temperature to form the RNP complex.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and wash your cells (e.g., primary T cells or iPSCs). Resuspend them in the appropriate electroporation buffer recommended by the system manufacturer for your specific cell type. Keep cells on ice.

- Electroporation: Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex and any electroporation enhancer. Electroporate using a pre-optimized program on a system like the Lonza Nucleofector or Thermo Fisher Neon.

- Recovery: Immediately transfer the electroporated cells to pre-warmed, enriched culture medium. Analyze editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-delivery.

FAQ 3: My experiment requires long-term, stable gene expression (e.g., for a genetic disease model or CRISPRa/i). Which delivery method should I use?

For long-term, stable expression, viral vectors, particularly lentiviral vectors (LVs), are the most suitable choice.

- Problem: Plasmids and RNPs are transient; their effects fade as cells divide, making them unsuitable for long-term expression needs.

- Solution: Use integrating viral vectors like LVs, which permanently insert the CRISPR machinery into the host genome, ensuring stable, long-term expression [34] [36].

- Caution: The prolonged expression from viral vectors increases the risk of off-target effects and immune responses. A common strategy to mitigate this is to create a stable cell line expressing only Cas9, then transiently deliver guide RNAs targeting different genes as needed [34].

FAQ 4: I am working on an in vivo model and need systemic delivery to the liver. What are my best options?

For in vivo delivery, especially to the liver, viral vectors and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are the leading technologies, each with distinct advantages.

- Problem: The delivery vehicle must survive in the bloodstream, home to the correct tissue, and efficiently enter the target cells.

- Solution:

- Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs): Excellent for liver-targeted in vivo delivery due to their natural tropism and ability to sustain long-term expression. A key limitation is their small ~4.7 kb packaging capacity, which is too small for the standard SpCas9 and its gRNA. Strategies to overcome this include using smaller Cas9 orthologs (e.g., SaCas9) or splitting the components across two AAVs [36] [37].

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): These are synthetic particles that efficiently encapsulate and deliver CRISPR cargo (like mRNA or RNP) to the liver. A major advantage is the potential for re-dosing, which is difficult with viral vectors due to immune responses. LNPs were successfully used in the first personalized in vivo CRISPR therapy [21].

Delivery System Comparison at a Glance

The following table provides a quantitative summary of the key characteristics of each delivery system to aid in your selection and troubleshooting.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of CRISPR Delivery Systems

| Feature | Plasmid DNA | Viral Vectors (AAV/LV) | RNP Electroporation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Editing Efficiency | Variable, often low to moderate [36] | High [34] [36] | High, consistently among the highest [34] [35] |

| Time to Onset of Editing | Slow (requires nuclear entry, transcription, translation) [34] | Slow (requires transcription/translation) [34] | Fast (minutes to hours); immediately active [34] [35] |

| Duration of Expression/Activity | Transient (days) | Stable/Long-term (weeks to months) [34] [36] | Very Transient (hours to days) [34] [38] |

| Risk of Off-Target Effects | High (prolonged Cas9 expression) [36] | High (prolonged Cas9 expression) [36] | Low (short Cas9 exposure) [36] [35] |

| Cargo Size Capacity | Very High (limited only by transfection) | Limited (AAV: <4.7 kb; LV: ~8 kb) [36] [37] | Limited only by electroporation efficiency |

| Ideal Cell Types | Easy-to-transfect immortalized lines (HEK293, HeLa) [34] | Broad range, including hard-to-transfect and in vivo targets [36] | Difficult cells (primary, stem, immune cells) [34] [35] |

| Key Advantage | Cost-effective, high throughput possible [34] | High efficiency, stable expression, excellent in vivo delivery [36] | High efficiency & precision, low toxicity, works in many cell types [35] |

| Primary Disadvantage | Low efficiency in difficult cells, cytotoxicity [34] | Cargo size limits (AAV), immunogenicity, risk of genomic integration [36] | Lower throughput, requires specialized equipment, can be harsh on cells [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Success

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in CRISPR Delivery | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-complexed RNP | The active CRISPR editing complex; delivers Cas protein and gRNA directly into cells for fast, precise editing with minimal off-target effects. | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 System (IDT) [35] |

| Electroporation Enhancer | Single-stranded DNA molecules that act as carriers during electroporation, improving RNP delivery into cells, enhancing editing efficiency, and improving cell viability. | Alt-R Electroporation Enhancer (IDT) [35] |

| Chemical Transfection Reagent | Lipid-based reagents that form complexes with nucleic acids or RNPs, enabling them to fuse with and cross the cell membrane. | Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX, RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher) [34] [35] |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | A viral vector for highly efficient in vivo or difficult-to-transfect in vitro delivery; known for a strong safety profile but limited cargo capacity. | Serotypes like AAV5, AAV8, AAV9 for specific tissue tropism [21] [37] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | A viral vector that integrates into the host genome, enabling long-term, stable expression of CRISPR components. Ideal for creating stable cell lines. | Third-generation, replication-incompetent for safety [36] |

| Nucleofector System | Specialized electroporation technology optimized for nuclear delivery, critical for high-efficiency editing in primary cells and stem cells. | Nucleofector (Lonza) [34] |

Decision Workflow for Selecting a Delivery System

Use the following decision diagram to systematically select the best delivery method for your experimental goals and cell type, a critical step in preemptively troubleshooting efficiency issues.

Designing the Donor Template for Efficient Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) and why is it used in CRISPR genome editing? Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a precise cellular mechanism for repairing DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) by using a homologous DNA sequence as a template [39]. In CRISPR-based genome engineering, researchers leverage this pathway by providing an exogenous donor template containing desired edits (e.g., insertions, mutations). When a CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSB occurs, this donor template can be used by the cell's repair machinery to generate precise, site-specific modifications, enabling applications like gene knock-ins, reporter tagging, and correction of pathogenic mutations [40].

Why is my HDR efficiency low even with a well-designed gRNA? Low HDR efficiency is a common challenge, primarily because the competing Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway is more active in most cells, especially post-mitotic cells like neurons [28] [40]. Beyond gRNA design, key factors affecting HDR efficiency include:

- Distance from Cut Site: The desired edit should be as close as possible to the Cas9 cut site, ideally within 10 nucleotides [41] [42].

- Donor Template Type and Design: The choice between single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donors must match the size of your insertion, with appropriately sized homology arms [42].

- Cell Cycle Stage: HDR is primarily active in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, so dividing cells typically show higher HDR efficiency [40].

- Template Delivery: The method of delivering the donor template and CRISPR components into the cell can significantly impact results [5].

How can I prevent Cas9 from re-cleaving the genome after a successful HDR event? To prevent repeated cutting, you must disrupt the CRISPR target site within the donor template. This can be achieved by [41] [42]:

- Introducing silent mutations in the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence or within the seed region of the gRNA binding site.

- Designing the insertion itself to split the target sequence or the PAM. This ensures that after successful HDR, the genomic locus is no longer recognized and cleaved by the Cas9-gRNA complex.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Knock-in Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient gRNA | Use bioinformatics tools to select a gRNA with high predicted activity and specificity. An NHEJ-mediated efficiency of at least 25% is recommended. Test multiple gRNAs. | [41] [5] |

| Suboptimal donor template design | Ensure the modification site is <10 nt from the cut site. Use the correct donor type and homology arm lengths (see Table 1). | [41] [42] |

| Low HDR pathway activity | Use small molecule HDR enhancers (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer) or consider transiently inhibiting key NHEJ factors to favor the HDR pathway. | [42] [40] |

| Poor delivery of CRISPR components | Optimize transfection methods (e.g., electroporation, lipofection) for your specific cell type. Consider using Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for faster editing and reduced off-target effects. | [5] [43] |

Problem 2: High Background of Random Integration

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Using dsDNA plasmid donors | Random integration is more common with double-stranded DNA templates. For inserts under 200 bp, switch to single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), which are less genotoxic and show higher HDR efficiency. | [39] [42] |

| Homology arms are too short | When using dsDNA donors (e.g., for large insertions), ensure homology arms are sufficiently long, typically 500-1000 bp for plasmids and 200-300 bp for long dsDNA fragments. | [41] [42] |

| Lack of selection or enrichment | Employ antibiotic selection or Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to enrich for successfully edited cells, thereby reducing the background of unedited cells and random integration events. | [10] [5] |

Quantitative Data for Donor Template Design

The design of the donor template is critical for HDR success. The table below summarizes key quantitative parameters based on current best practices.

Table 1: Donor Template Design Specifications

| Template Type | Ideal Insert Size | Homology Arm Length | Key Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssODN (single-stranded oligo) | 1 - 50 bp (up to ~200 bp total) | 30 - 60 nt | Highest HDR efficiency for small edits. Total length often kept under 200 nt. | [39] [42] |

| dsDNA Donor Block (linear dsDNA) | 200 bp - 3 kb | 200 - 300 bp | Less toxic than plasmid donors. Suitable for medium to large insertions. | [42] |

| Plasmid Donor | Large insertions (e.g., fluorescent reporters, selection cassettes) | 500 - 1000 bp | Can have low HDR efficiency; consider linearizing the plasmid or using self-cleaving designs to improve efficiency. | [41] [39] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing and Using an ssODN Donor for a Point Mutation