Boosting CRISPR HDR Efficiency: Advanced Strategies for Precision Genome Editing in Research and Therapy

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is the cornerstone of precise CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, enabling targeted gene insertions, corrections, and the creation of sophisticated disease models.

Boosting CRISPR HDR Efficiency: Advanced Strategies for Precision Genome Editing in Research and Therapy

Abstract

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is the cornerstone of precise CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, enabling targeted gene insertions, corrections, and the creation of sophisticated disease models. However, its low efficiency compared to error-prone repair pathways remains a significant bottleneck. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the latest strategies to enhance HDR outcomes. We explore the foundational science of DNA repair pathway competition, detail cutting-edge methodological advances in donor template design and cellular pathway modulation, address critical troubleshooting for optimizing efficiency and fidelity, and discuss robust validation techniques to accurately assess editing outcomes. By synthesizing recent discoveries from 2024 and 2025, this review serves as a strategic roadmap for overcoming the key challenges in achieving high-efficiency, high-precision genome editing.

The HDR Challenge: Understanding the Cellular Battlefield of DNA Repair

FAQ: Why does NHEJ happen more often than HDR in my experiments?

In most cells, the Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway is the dominant and more active repair mechanism for double-strand breaks (DSBs) across all phases of the cell cycle. In contrast, the Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway is active only during the S and G2 phases, when a sister chromatid is available to use as a template. Furthermore, NHEJ is a faster process, as it simply ligates the broken DNA ends together without needing a homologous template [1] [2].

The table below summarizes the key competitive advantages of NHEJ.

| Feature | NHEJ | HDR |

|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | None (error-prone) | Homologous DNA template (precise) |

| Cell Cycle Activity | Active throughout all phases (G1, S, G2) [3] | Primarily restricted to S and G2 phases [1] [3] |

| Speed & Efficiency | Fast, "first-responder" pathway | Slower, more complex process |

| Primary Role in CRISPR | Ideal for gene knockouts (indels) | Ideal for precise knock-ins and specific edits |

Troubleshooting Guide: Strategies to Favor HDR

FAQ: How can I tip the balance in favor of HDR in my experiments?

You can coax cells to favor HDR by using strategic interventions that either suppress the NHEJ pathway or enhance the HDR pathway directly.

Suppressing Competing Repair Pathways

Inhibiting key molecules in the NHEJ and other alternative repair pathways can significantly reduce off-target editing and increase HDR efficiency.

- NHEJ Inhibition: Using small molecule inhibitors like Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 targets the NHEJ pathway [4].

- SSA & MMEJ Inhibition: Recent research shows that even with NHEJ inhibited, other pathways like Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) and Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) contribute to imprecise repair. Suppressing these by inhibiting their key effectors (POLQ for MMEJ and Rad52 for SSA) can further improve HDR accuracy [4].

The table below lists key reagents for pathway suppression.

| Research Reagent | Target Pathway | Key Effector | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | NHEJ | DNA Ligase IV complex | Small molecule inhibitor to suppress error-prone NHEJ [4]. |

| ART558 | MMEJ | POLQ (Pol Theta) | Small molecule inhibitor to reduce large deletions and complex indels [4]. |

| D-I03 | SSA | Rad52 | Small molecule inhibitor to reduce asymmetric HDR and other imprecise integration events [4]. |

Enhancing HDR Efficiency Directly

You can also directly stimulate the HDR machinery by modulating protein expression or optimizing the donor template.

- Overproducing HDR-Related Proteins: Studies have shown that overexpression of RAD52, a key protein in homologous recombination, can enhance the integration of single-stranded DNA templates, in some cases increasing HDR efficiency nearly 4-fold [5].

- Optimizing Donor Template Design: The design of your donor DNA is critical.

- 5' Modifications: Adding a 5'-biotin or 5'-C3 spacer to your donor DNA can substantially boost single-copy HDR integration by up to 8-fold and 20-fold, respectively, potentially by protecting the ends and improving recruitment to the break site [5].

- Using Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA): ssDNA donors are often favored over double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) due to lower cytotoxicity and higher HDR efficiency. For long insertions, methods like Easi-CRISPR that use long single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors can achieve efficiencies of 25-50% [6] [3].

- Denaturing dsDNA Templates: Heat-denaturing long double-stranded DNA templates before delivery has been shown to enhance precise editing and reduce the formation of unwanted template concatemers [5].

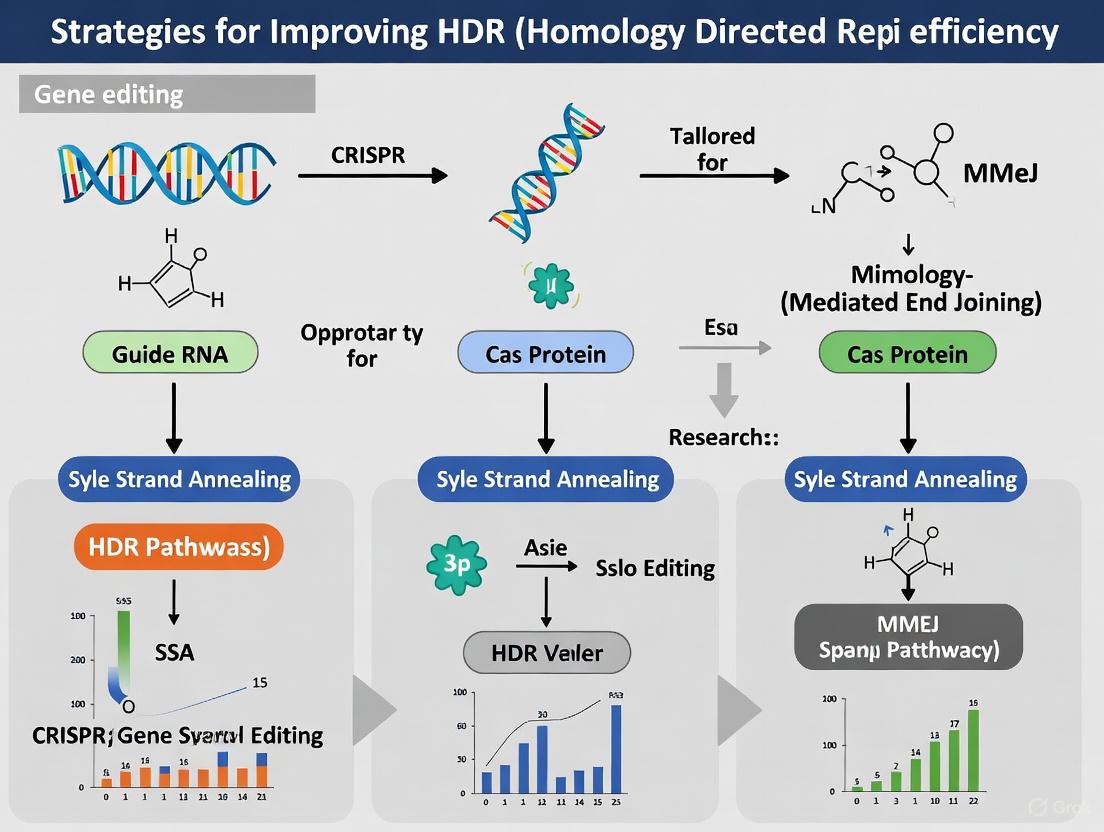

Diagram 1: The competitive balance between NHEJ and HDR pathways and strategies to shift the outcome.

Quantitative Data on Editing Outcomes

FAQ: How much can these strategies actually improve my HDR rates?

The effectiveness of these strategies is highly dependent on your experimental system, including the target locus, cell type, and nuclease platform [7]. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from recent studies.

| Experimental Strategy | Quantitative Effect on HDR | Effect on Undesired Outcomes | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibition (Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) | Increased knock-in efficiency from ~6% to ~22% (approx. 3-fold) [4] | Significantly reduced small indels [4] | Human RPE1 cells |

| SSA Inhibition (Rad52 suppression) | --- | Reduced asymmetric HDR and other imprecise donor integrations [4] | Improved precision, not necessarily overall efficiency |

| MMEJ Inhibition (POLQ suppression) | Increased perfect HDR frequency [4] | Reduced large deletions (≥50 nt) and complex indels [4] | Human RPE1 cells |

| RAD52 Supplementation | Increased ssDNA integration nearly 4-fold [5] | Accompanied by higher template multiplication [5] | Mouse zygote microinjection |

| 5'-Biotin Donor Modification | Up to 8-fold increase in single-copy integration [5] | --- | Mouse embryo experiment |

| 5'-C3 Spacer Donor Modification | Up to 20-fold rise in correctly edited mice [5] | --- | Mouse embryo experiment |

| Denatured DNA Template | Increased correctly targeted animals from 2% (dsDNA) to 8% (ssDNA) [5] | Reduced template multiplication from 34% to 17% [5] | Mouse Nup93 locus targeting |

Experimental Protocol: A Sample Workflow for Enhancing HDR

This protocol outlines a methodology for improving HDR efficiency in cell culture, based on strategies cited above [4] [5] [3].

Objective: To achieve precise knock-in of a fluorescent tag at an endogenous gene locus in human cells while minimizing NHEJ-derived indels.

Key Reagents:

- RNP Complex: Recombinant Cas9 or Cpf1 protein and synthetic guide RNA (crRNA/tracrRNA).

- Donor Template: Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) with homology arms, ideally with 5'-biotin or 5'-C3 modification [5].

- Pathway Inhibitors: Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (NHEJi), ART558 (MMEJi), D-I03 (SSAi) [4].

- Cells: hTERT-immortalized RPE1 or other relevant cell line.

Procedure:

- Prepare Donor Template: Design an ssDNA donor with 40+ base homology arms. Synthesize the oligonucleotide with a 5' modification (e.g., biotin) to enhance HDR efficiency [5] [3].

- Form RNP Complex: Pre-complex the Cas protein with the guide RNA to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

- Electroporation: Co-deliver the RNP complex and the donor template into your cells via electroporation.

- Inhibitor Treatment: Immediately after electroporation, treat the cells with a cocktail of small molecule inhibitors (e.g., NHEJi, MMEJi, SSAi) for 24 hours to transiently suppress competing repair pathways during the critical DSB repair window [4].

- Analysis: After 3-4 days, analyze the editing outcomes. Use flow cytometry to assess knock-in efficiency (if using a fluorescent tag) and long-read amplicon sequencing (e.g., PacBio) coupled with computational genotyping (e.g., knock-knock framework) to comprehensively quantify perfect HDR, imprecise integration, and indel frequencies [4].

Diagram 2: A sample experimental workflow for enhancing HDR efficiency.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is the efficiency of precise genome editing via HDR so low in my experiments?

Answer: The low efficiency of Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is primarily due to strong cellular competition from other, faster DNA repair pathways.

- Pathway Competition: When CRISPR-Cas9 creates a double-strand break (DSB), the cell's repair machinery is activated. The dominant and most rapid pathway is Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), which operates throughout the cell cycle and simply rejoins the broken DNA ends, often introducing small insertions or deletions (indels). HDR, in contrast, is a more complex process restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and requires a homologous DNA template [8] [9].

- Alternative Error-Prone Pathways: Even when NHEJ is suppressed, alternative pathways like Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) and Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) can repair the break. These pathways use short or long homologous sequences, respectively, but are error-prone and often result in deletions, further reducing the yield of perfect HDR events [10] [11].

FAQ 2: What are the key differences between NHEJ, HDR, MMEJ, and SSA?

Answer: These four pathways are distinguished by their mechanisms, template requirements, and fidelity, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Key DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Pathway | Full Name | Mechanism | Template Required? | Fidelity | Key Effector Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ | Non-Homologous End Joining | Direct ligation of broken ends [9] | No | Error-Prone (often causes small indels) [9] | Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, DNA Ligase IV [12] |

| HDR | Homology-Directed Repair | Uses homologous sequence as a template for precise repair [9] | Yes | High-Fidelity (precise) [9] | BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51, MRN Complex [9] [12] |

| MMEJ | Microhomology-Mediated End Joining | Annealing of short microhomology regions (2-20 nt) flanking the break [11] | No | Error-Prone (causes deletions) [11] | PARP1, POLθ (POLQ), DNA Ligase 3 [10] [11] |

| SSA | Single-Strand Annealing | Annealing of long homologous repeats (>20 nt) flanking the break [10] | No | Error-Prone (causes large deletions) [10] | RAD52, MRN Complex [10] |

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally inhibit competing pathways to improve HDR efficiency?

Answer: You can bias repair toward HDR by using small-molecule inhibitors or genetic knockdown to target key factors of competing pathways.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Modulating DNA Repair Pathways

| Reagent / Method | Target Pathway | Key Component Inhibited | Effect on Editing Outcomes | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 [10] | NHEJ | DNA-PKcs (implied) | Increases perfect HDR frequency; reduces small indels [10] | A common first-step enhancement strategy. |

| ART558 [10] | MMEJ | POLQ (Polymerase Theta) | Reduces large deletions and complex indels; can increase HDR [10] | Effective in combination with NHEJ inhibition. |

| D-I03 [10] | SSA | RAD52 | Reduces asymmetric HDR and other imprecise donor integrations [10] | Effect may depend on the nature of the DNA cleavage ends. |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization | NHEJ vs. HDR | N/A (chemicals used for sync) | Increases HDR by enriching for S/G2 phase cells [9] | Can be technically challenging and impact cell health. |

Experimental Protocol: Pathway Inhibition for Enhanced HDR

- Design and Complex Formation: Form Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes by pre-incubating your chosen Cas nuclease (e.g., Cas9) with synthesized, chemically modified guide RNAs [13].

- Delivery and Electroporation: Co-deliver the RNP complexes and your donor DNA template into the target cells (e.g., hTERT-immortalized RPE1 cells) via electroporation [10].

- Inhibitor Treatment: Immediately after delivery, treat the cells with pathway-specific inhibitors.

- Use a commercial NHEJ inhibitor like Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2.

- For broader suppression, combine with ART558 (MMEJ inhibitor) and/or D-I03 (SSA inhibitor).

- A typical treatment duration is 24 hours, as HDR often occurs within this window post-Cas9 delivery [10].

- Analysis: After 3-4 days, analyze editing outcomes. Use flow cytometry to assess knock-in efficiency if using a fluorescent tag. For precise repair pattern analysis, perform long-read amplicon sequencing (e.g., PacBio) on the target locus and genotype the results with a computational framework like

knock-knock[10].

FAQ 4: My knock-in results show partial or incorrect integration of the donor template. What could be the cause?

Answer: Imprecise donor integration, such as "asymmetric HDR" (where only one end integrates correctly), is a common issue often linked to the Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) pathway. Even with NHEJ inhibition, the SSA pathway can still use the homology arms on your donor DNA to catalyze erroneous repair, leading to partial integration or duplication of homology arms [10].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Observation of various imprecise integration patterns (blunt, asymmetric, imperfect) despite NHEJ inhibition.

- Solution: Suppress the SSA pathway in addition to NHEJ inhibition. Using a Rad52 inhibitor (e.g., D-I03) during the initial repair period has been shown to specifically reduce asymmetric HDR and other faulty integration events, thereby increasing the proportion of perfect HDR [10].

Pathway Diagrams and Experimental Workflows

DNA Repair Pathway Mechanics

HDR Enhancement Experimental Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: Why is Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle?

HDR is restricted to these phases because it relies on a sister chromatid as a repair template, which is only available after DNA replication has occurred during the S phase. Additionally, key proteins in the HDR pathway are selectively active during these cell cycle stages [9].

FAQ: What are the main DNA repair pathways that compete with HDR after a CRISPR-Cas9 induced double-strand break (DSB)?

The primary competing pathways are:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone pathway that is active throughout all cell cycle phases and often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) [9].

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): An alternative, highly mutagenic pathway that can generate larger deletions [9].

FAQ: What practical strategies can I use to improve HDR efficiency in my experiments?

Key strategies include:

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Transiently synchronizing your cell population in the S/G2 phases.

- NHEJ Inhibition: Using chemical inhibitors or genetic knockdown of key NHEJ factors.

- Donor Template Optimization: Employing single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors with optimized design.

- HDR Pathway Enhancement: Overexpressing crucial HDR factors.

Experimental Protocols for HDR Enhancement

Chemical Inhibition of NHEJ

Detailed Methodology:

- Transfect cells with your CRISPR-Cas9 components (e.g., Cas9-gRNA RNP complex and donor DNA).

- Treat cells with small-molecule inhibitors targeting key NHEJ proteins. Common inhibitors include:

- The typical treatment window is 24-48 hours post-transfection. Optimize concentration and duration for your specific cell type to minimize cytotoxicity.

Cell Cycle Synchronization

Detailed Methodology:

- Use chemicals to arrest cells at the G1/S boundary before transfection.

- Common Reagents: Aphidicolin, thymidine, or lovastatin.

- Post-arrest, release cells into fresh medium to allow them to progress synchronously into S phase.

- Perform CRISPR transfection/transduction immediately after release to maximize the number of Cas9-induced DSBs occurring in the S/G2 phases, where HDR is active [9].

Using Optimized Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Donors

Detailed Methodology:

- Design ssDNA donors (e.g., ssODNs) with symmetrical homology arms.

- Optimal Arm Length: Typically 40-60 nucleotides on each side of the edit [3].

- Modifications: Consider phosphorothioate (PS) modifications at the 5' and 3' ends to increase donor stability and resistance to exonuclease degradation [3].

- Co-deliver the optimized ssDNA donor with your CRISPR-Cas9 system.

HDR and Competing DNA Repair Pathways

Quantitative Data on HDR Enhancement Strategies

Key Small-Molecule Inhibitors for Modulating DNA Repair

| Inhibitor / Reagent | Target Pathway | Mechanism of Action | Effect on HDR | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NU7441 [9] | NHEJ | DNA-PKcs inhibitor | Increases HDR efficiency | 0.5–1 µM |

| M3814 [3] | NHEJ | DNA-PKcs inhibitor | Increases HDR efficiency | Cited in patent application |

| KU0060648 [9] | NHEJ | DNA-PKcs & PI3K-related kinase inhibitor | Increases HDR efficiency | Varies by cell type |

| Roscovitine (Seliciclib) [9] | Cell Cycle | CDK inhibitor | Synchronizes cells at G1/S; enriches S/G2 population | 10–25 µM |

| AZD-7648 [9] | NHEJ | DNA-PKcs inhibitor | Increases HDR efficiency | Varies by cell type |

| RAD51 agonists (e.g., RS-1) [9] | HDR | RAD51 stabilizer | Enhances strand invasion step of HDR | 5–25 µM |

Comparison of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Feature | NHEJ | MMEJ | HDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Used | None | Microhomology regions | Homologous donor (e.g., sister chromatid) |

| Fidelity | Error-Prone | Highly Error-Prone | Precise |

| Primary Phase | All phases | S/G2 [14] | S and G2 phases [9] |

| Key Initiating Factors | KU70/KU80, 53BP1, DNA-PKcs | PARP1, Pol θ, MRN/CtIP (limited resection) | MRN Complex, CtIP |

| Critical Effector | DNA Ligase IV/XRCC4 | DNA Pol θ | RAD51, BRCA2 |

| Typical Outcome | Small indels | Larger deletions | Precise gene correction/insertion |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Tool | Function in HDR Editing | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ssDNA Donors (ssODNs) [3] | Provides template for precise repair; lower cytotoxicity than dsDNA. | Optimize homology arm length (40+ bases); consider phosphorothioate modifications. |

| HDR Booster Modules [3] | Fusion proteins (e.g., nCas9-CtIP) designed to enhance HDR efficiency. | Can bias repair toward HDR by promoting initial resection steps. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) [14] | Efficient delivery of Cas9 RNP to hard-to-transfect cells (e.g., neurons). | Pseudotype choice (e.g., VSVG, BRL) critically impacts delivery efficiency. |

| Cell Cycle Reporters (e.g., Fucci) | Identifies and/or sorts cells in S/G2 phases for targeted editing. | Allows for tracking cell cycle progression without fixation. |

| NHEJ Chemical Inhibitors [3] [9] | Suppresses competing error-prone pathway to favor HDR. | Requires titration to balance HDR boost with potential cytotoxicity. |

In CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing, achieving precise modifications through Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a fundamental goal for researchers. However, HDR competes with the error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway, which often results in unpredictable insertions or deletions (indels) [15] [16]. This competition significantly limits the efficiency of precise gene knock-ins, point mutations, and gene corrections—a central challenge in therapeutic gene editing and functional genomics. The key to tilting this balance toward HDR lies in understanding and manipulating specific DNA repair proteins, primarily RAD51, RAD52, and the MRN complex (MRE11, RAD50, and NBS1). This technical support center details how these proteins function, how their activity can be enhanced, and how to troubleshoot common experimental hurdles to successfully improve HDR outcomes.

Core Protein Functions & Mechanisms

Q1: What are the specific roles of RAD51, RAD52, and the MRN complex in the HDR pathway?

The HDR pathway is a carefully coordinated process that requires multiple proteins to work in sequence after a CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand break (DSB). Below is a summary of their specialized functions.

Table: Core Functions of Key HDR Proteins

| Protein/Complex | Primary Function in HDR | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| MRN Complex | Initial DSB sensing and end resection (5' to 3') to create single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs [17]. | Recruits and activates ATM; stabilizes the DSB site [17]. |

| RAD51 | Forms a nucleoprotein filament on ssDNA; catalyzes the central step of strand invasion into the homologous donor template [17] [18]. | Loaded with the help of BRCA2 and PALB2; displaces RPA [17]. |

| RAD52 | Mediates the loading of RAD51 onto RPA-coated ssDNA (in yeast) and promotes single-strand annealing (SSA); serves as a backup mediator in human cells, crucial in BRCA-deficient contexts [19] [20]. | Has annealing activity; synthetically lethal with BRCA1/BRCA2 loss [20]. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential involvement of these proteins in the HDR pathway following a DSB.

Troubleshooting Low HDR Efficiency

Q2: My HDR efficiency is consistently low. What are the primary strategies to enhance it?

Low HDR efficiency is often due to the dominance of the NHEJ pathway. Effective strategies focus on either suppressing NHEJ or directly stimulating the HDR machinery.

- Inhibit the NHEJ Pathway: Transiently inhibiting key NHEJ proteins can shift the repair balance toward HDR. This can be achieved using small molecule inhibitors like SCR7 (targeting DNA Ligase IV) or M3814 (targeting DNA-PKcs) [19] [21]. Alternatively, you can use RNAi to knock down factors like KU70, KU80, or DNA Ligase IV [19].

- Stimulate the HDR Pathway Directly: As detailed in the following sections, you can boost HDR by:

- Optimize Donor Template Design: The design and delivery of your donor template are critical.

- Use single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors instead of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) where possible, as they are generally more efficient and less cytotoxic [21].

- For ssDNA donors, incorporate RAD51-preferred sequence motifs (e.g., containing a "TCCCC" motif) at the 5' end to enhance RAD51 binding and recruitment, a chemical-free method shown to significantly boost HDR [21].

- Chemically modify the 5' ends of donor templates with biotin or a C3 spacer to protect the ends and improve the rate of single-copy integration [5].

Experimental Protocols & Reagents

Q3: What are specific experimental protocols for implementing HDR-enhancing strategies?

Here are detailed methodologies for two key approaches: RAD51/RAD52 overexpression and MRN complex recruitment.

Protocol 1: Enhancing HDR via RAD51 or RAD52 Expression

This protocol involves co-expressing RAD51 or RAD52 with the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Plasmid Construction:

- For RAD51, clone the human RAD51 coding sequence into an all-in-one CRISPR vector downstream of a T2A or P2A self-cleaving peptide sequence, following Cas9 and a selection marker (e.g., EGFP/Puromycin) [18]. This ensures coordinated expression.

- For RAD52, clone the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad52 (ScRad52) gene into an expression vector under a strong promoter (e.g., CBh) [19]. Alternatively, create a fusion construct where ScRad52 is directly fused to the C-terminus of Cas9 via a flexible linker [19].

Cell Transfection and Selection:

- Transfect your target cells (e.g., HEK293T) with the constructed plasmid and your sgRNA and donor template.

- At 48 hours post-transfection, replace the media and begin selection with an appropriate antibiotic (e.g., Puromycin) for 72 hours to enrich for successfully transfected cells [18].

Efficiency Validation:

- Genotypic Analysis: Use T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay or tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) to assess mutation rates at the target locus [18]. For precise HDR, perform PCR followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) or Sanger sequencing of cloned amplicons.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Confirm editing success at the protein level via western blotting or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) if editing introduces or disrupts a fluorescent protein [18].

Protocol 2: Enhancing HDR via MRN Complex Recruitment

This protocol uses a chimeric Cas9 protein fused to an MRN-recruiting domain to localize the repair machinery.

Chimeric Cas9 Construction:

- Fuse the N-terminal 126-amino-acid intrinsically disordered domain from the HSV-1 alkaline nuclease (UL12), known to recruit the MRN complex, to the N- or C-terminus of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) [22]. Ensure the fusion preserves the nuclear localization signals of Cas9.

Delivery into Cells:

- Deliver the chimeric Cas9 as either plasmid DNA or pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- For plasmid transfection, use standard methods (e.g., calcium phosphate, PEI, or commercial reagents) to co-deliver the chimeric Cas9 plasmid, sgRNA plasmid, and donor template [22].

- For RNP delivery, complex in vitro transcribed sgRNA with purified chimeric Cas9 protein. Then, transfect this RNP complex along with the donor template using a reagent like Lipofectamine CRISPRMax [22].

Efficiency Assessment:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for HDR Enhancement Experiments

| Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HDR Enhancer (RS-1) | Small molecule that stabilizes RAD51-ssDNA filaments. | Add to cell culture media post-transfection to stimulate the strand invasion step of HDR [19]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitor (SCR7) | Small molecule inhibitor of DNA Ligase IV. | Add to media to transiently suppress the competing NHEJ pathway, favoring HDR [19]. |

| Chimeric Cas9-UL12 | Cas9 fused to the MRN-recruiting domain of HSV-1 UL12. | Used in RNP or plasmid formats to locally recruit the MRN complex to the DSB, boosting HDR [22]. |

| 5'-Modified ssDNA Donor | ssDNA donor with 5' biotin or C3 spacer modifications. | Use as a repair template to reduce concatemerization and improve single-copy HDR integration [5]. |

| Modular ssDNA Donor | ssDNA donor with 5' RAD51-preferred binding sequences (e.g., "TCCCC" motif). | A chemical-free donor design that augments affinity for RAD51, enhancing HDR efficiency [21]. |

Quantitative Data & Comparisons

Q4: Is there quantitative data comparing the efficacy of these different HDR-enhancement methods?

Yes, various studies have quantified the improvement in HDR efficiency using these strategies. The following table summarizes key findings for easy comparison.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of HDR Enhancement Strategies

| Enhancement Strategy | Experimental System | Reported HDR Efficiency | Key Findings and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAD51 Overexpression | Human HEK293T cells (GAPDH KO) | Editing efficiency increased >2.5-fold [18]. | Enhanced both knock-out and knock-in efficiency. |

| RAD52 Supplementation | Mouse zygotes (Nup93 cKO model) | HDR rate increased to 26% (from 2% with dsDNA) [5]. | Accompanied by a higher rate of template multiplication. |

| Cas9-UL12 Fusion (MRN Recruitment) | Human HEK293FT, HCT116, HeLa cells | ~2-fold increase over standard Cas9 [22]. | Effect depended on the MRN-recruiting activity of the UL12 domain. |

| 5'-Biotin Modified Donor | Mouse zygotes | Single-copy integration increased up to 8-fold [5]. | Reduces unwanted template multimerization. |

| 5'-C3 Spacer Modified Donor | Mouse zygotes | Correctly edited mice increased up to 20-fold [5]. | Highly effective in boosting single-copy HDR. |

| RAD51-Preferred ssDNA Module | HEK 293T-BFP reporter cells | HDR efficiency up to 90.03% (median 74.81%) when combined with M3814 [21]. | A chemical-free strategy that synergizes with NHEJ inhibition. |

FAQs on Protein-Specific Issues

Q5: Why would I choose to target RAD52 instead of RAD51, given RAD51's central role?

While RAD51 is the core recombinase, RAD52 offers a unique strategic advantage, particularly in certain genetic contexts. In human cells, the primary mediator for loading RAD51 is actually the BRCA2 protein, not RAD52 [20]. However, in cells with BRCA1, BRCA2, or PALB2 deficiencies (e.g., some cancer cell lines), RAD52 becomes essential as a backup loader. This creates a synthetic lethal interaction, where inhibiting RAD52 is lethal only to the BRCA-deficient cells [20]. Therefore, modulating RAD52 activity can be a more targeted strategy in these contexts, and its strong annealing activity also makes it critical for the SSA sub-pathway of HDR.

Q6: Are there any pitfalls or downsides to overexpressing RAD51 or RAD52?

Yes, potential downsides must be considered. A primary concern with enhancing HDR factors is the potential for increased off-target integration or aberrant recombination events. For instance, one study noted that while RAD52 supplementation significantly boosted precise HDR, it was also accompanied by a near doubling of unwanted template multiplication (concatemer formation) [5]. Furthermore, forced overexpression of these powerful recombinases could, in theory, lead to genomic instability by promoting recombination between non-allelic sequences with low homology. It is crucial to carefully optimize the expression levels and timing of these proteins to maximize on-target HDR while minimizing unintended consequences.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on HDR Efficiency

FAQ: Why is my knock-in efficiency so low, and why do I see random insertions instead of precise edits?

The dominant DNA repair pathway in most cells, particularly postmitotic cells like neurons, is the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway. This pathway is active throughout the cell cycle and often outcompetes the precise Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway, leading to a high frequency of insertions and deletions (indels) rather than your desired precise edit [14] [8]. The table below summarizes common issues and solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low HDR efficiency | NHEJ outcompeting HDR in dividing cells | Use single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) templates; inhibit NHEJ pathways chemically or genetically [5] [8]. |

| Random insertion/deletion (indels) | NHEJ-dominated repair in non-dividing cells | Design gRNAs compatible with MMEJ/SSA; use Cas9 proteins with altered PAM specificities [14]. |

| Donor DNA multimerization/ concatemers | End-joining of linear double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donor templates | Denature long dsDNA templates into ssDNA; use 5'-end modifications (e.g., C3 spacer, biotin) on donor DNA [5]. |

| Low HDR in iPSCs & HSPCs | Cell-type specific repair pathway dominance | Supplement with HDR-enhancing proteins (e.g., RAD52, commercial Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein) during editing [5] [23]. |

| Extended editing time in neurons | Slow DSB repair kinetics in postmitotic cells | Allow extended time (up to 2 weeks) for indel accumulation; use virus-like particles (VLPs) for efficient RNP delivery [14]. |

FAQ: My edits work in cell lines but fail in primary or non-dividing cells. Why?

DNA repair is not universal across cell types. Dividing cells, such as iPSCs, frequently use repair pathways like microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), which can create larger deletions. In contrast, non-dividing cells (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes) predominantly use classical NHEJ, resulting in smaller indels and a higher proportion of unedited outcomes [14]. Furthermore, homology-directed repair (HDR) is largely restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, making it inherently inefficient in non-dividing cells [14] [8].

Quantitative Data on HDR Optimization Strategies

The following table summarizes experimental data from a large-scale study targeting the Nup93 locus in mouse zygotes, comparing the effectiveness of various strategies to improve HDR outcomes [5].

Table: Impact of Different Strategies on HDR Efficiency and Template Multiplication

| crRNAs/Orientation | DNA Type | 5' End Modification | Additional Factor | F0 HDR % | F0 Head-to-Tail % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| crR1-7 (±) | dsDNA | 5'-P | no | 2% | 34% |

| crR1-7 (±) | dsDNA denatured | 5'-P | no | 8% | 17% |

| crR1-7 (±) | dsDNA denatured | 5'-P | RAD52 | 26% | 30% |

| crR1-7 (±) | dsDNA | 5'-C3 Spacer | no | 40% | 9% |

| crR1-7 (±) | dsDNA denatured | 5'-C3 Spacer | no | 42% | 5% |

| crR1-7 (±) | dsDNA | 5'-Biotin | no | 14% | 5% |

Key findings from the data:

- Donor Denaturation: Heat-denaturing a long dsDNA template into ssDNA boosted precise HDR by 4-fold (from 2% to 8%) and reduced template concatemer formation (head-to-tail) by half [5].

- RAD52 Supplementation: Adding RAD52 protein to ssDNA templates increased HDR efficiency dramatically to 26%, a 13-fold increase over standard dsDNA. However, this came with a trade-off of increased template multiplication [5].

- 5' End Modifications: Modifying the 5' end of the donor DNA was highly effective. The 5'-C3 spacer modification yielded the highest HDR efficiency (40-42%) while keeping concatemer formation low (5-9%). 5'-Biotin modification was also effective at reducing multimerization [5].

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing HDR

Protocol 1: Using Denatured DNA Templates and RAD52

This protocol is adapted from methods used to generate conditional knockout mouse models, which resulted in a 4-fold to 13-fold increase in precise editing [5].

- Donor DNA Design: Synthesize a long (e.g., ~600 bp) double-stranded DNA template with homologous arms (60 bp and 58 bp) and monophosphorylated 5' ends.

- Denaturation: Heat-denature the dsDNA template to create a single-stranded donor for microinjection or transfection.

- Complex Formation: Co-inject/co-transfect the denatured DNA template with CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. For the test condition, supplement the mix with recombinant human RAD52 protein.

- Analysis: Screen for precise HDR events and use Southern blot analysis to detect single-copy integrations and monitor template multiplication.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening for HDR-Enhancing Chemicals

This protocol outlines steps to identify small molecules that can shift the DNA repair balance toward HDR [24] [25].

- Plate Design: Seed cells expressing CRISPR-Cas9 components and a HDR reporter system into 96-well plates.

- Chemical Library Treatment: Treat cells with a library of small molecules (e.g., HDAC inhibitors, autophagy inducers). Include positive and negative controls.

- Dual Assay Execution: Simultaneously perform a colorimetric assay (e.g., LacZ) to quantify HDR efficiency and a viability assay to control for cytotoxicity.

- Data Analysis: Use a plate reader to collect data. Normalize HDR readouts to cell viability to identify compounds that specifically enhance HDR without detrimental effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Optimizing HDR in CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function in HDR Enhancement |

|---|---|

| Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Donor | Serves as an optimal repair template; reduces concatemer formation compared to dsDNA [5]. |

| RAD52 Protein | A recombination mediator that promotes strand invasion; can significantly boost ssDNA integration [5]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein | A proprietary, protein-based solution that shifts repair pathway balance toward HDR in challenging cells like iPSCs and HSPCs [23]. |

| 5'-C3 Spacer / 5'-Biotin Modifications | Chemical modifications to the 5' end of donor DNA that prevent ligation and multimerization, favoring single-copy HDR integration [5]. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered delivery vehicles for efficient transduction of Cas9 RNP into hard-to-transfect cells, such as human neurons [14]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

DNA Repair Pathway Competition

HDR Enhancement Experimental Workflow

Practical Strategies for Enhancing HDR in the Lab

FAQs on Donor Template Design

FAQ 1: Should I choose a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donor template for HDR?

The choice between ssDNA and dsDNA donors depends on the size of your intended insertion and the desired balance between efficiency and simplicity.

- ssDNA Donors are typically preferred for introducing shorter edits, such as point mutations or short tags, due to their generally higher HDR efficiency and lower cytotoxicity compared to dsDNA donors [3] [15]. They are effective even with very short homology arms (30-60 nucleotides) [26] [27].

- dsDNA Donors are more suitable for inserting larger DNA fragments (>1-2 kb) [27]. However, they often require significantly longer homology arms (200 bp to over 2,000 bp) to achieve reasonable HDR efficiency and are more prone to random integration or concatemer formation [26] [5].

Table 1: Comparison of ssDNA and dsDNA Donor Templates

| Feature | ssDNA Donors | dsDNA Donors |

|---|---|---|

| Best For | Point mutations, short insertions (a few hundred bases) [27] [3] | Large insertions (1 kb and above) [27] |

| Typical Homology Arm Length | 30-100 nucleotides [26] [27] | 200-2000+ base pairs [26] [27] |

| Efficiency | Generally higher for small edits [3] [15] | Lower, but necessary for large inserts [27] |

| Cytotoxicity | Lower [3] [15] | Higher |

| Common Issues | Limited insert size | Concatemer formation, random integration [5] |

FAQ 2: What is the optimal length for homology arms?

The optimal homology arm length is primarily determined by the type of donor DNA you are using.

- For ssDNA donors, arms as short as 30-40 nucleotides can support efficient HDR [26] [27]. Some studies report that increasing the arm length from 30 nt to ~60-97 nt does not necessarily lead to a significant increase in HDR efficiency, though it may influence the repair pathway choice [26].

- For dsDNA donors, arm length is much more critical. While very short arms (50 bp) can work at low efficiency, arms of 200-300 bp are often sufficient, and for maximum efficiency, arms can be extended to 500-2000 bp or even longer [26] [27].

Table 2: Recommended Homology Arm Lengths

| Donor Type | Recommended Arm Length | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| ssDNA | 30 - 100 nt | HDR achieved with 30 nt arms in potato; 40+ nt recommended for robustness [26] [27] [3]. |

| dsDNA | 200 - 300 bp (sufficient) 500 - 2000+ bp (optimal for large inserts) | 200-300 bp sufficient for HDR in mammalian cells; efficiency increases with arm length up to 2,000 bp [26] [27]. |

FAQ 3: How can I further enhance HDR efficiency with ssDNA donors?

Several advanced strategies can significantly boost the performance of ssDNA donors by promoting their recruitment to the double-strand break site.

Template Modifications:

- 5'-End Modifications: Adding 5'-biotin or a 5'-C3 spacer to the donor DNA can enhance single-copy integration by up to 8-fold and 20-fold, respectively, by preventing multimerization and improving localization to the break site [5].

- HDR-Boosting Modules: Engineering RAD51-preferred binding sequences (e.g., containing a "TCCCC" motif) into the 5' end of the ssDNA donor can augment its affinity for the RAD51 protein, a key player in HDR. This chemical-free method has been shown to increase HDR efficiency dramatically, especially when combined with NHEJ inhibitors [28].

Pharmacological and Protein Interventions:

- Inhibiting Competing Pathways: Transiently inhibiting the NHEJ or MMEJ pathways with small molecules (e.g., DNA-PKcs inhibitors) can shift repair toward HDR [29].

- Supplementing with Repair Proteins: Adding RAD52 protein to the editing mix has been shown to increase ssDNA integration by nearly 4-fold, though it can be accompanied by increased template multiplication [5].

- HDAC Inhibitors: Compounds like tacedinaline and entinostat can upregulate the expression of CRISPR system components (Cas9, sgRNA), thereby enhancing HDR efficiency in some cell types [30].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing HDR Efficiency Using an ssDNA Donor with Short Homology Arms

This protocol is adapted from a study in potato protoplasts and can be adapted for mammalian cells to rapidly test donor designs [26].

- Design ssDNA Donor: Synthesize a single-stranded donor oligo with your desired edit (e.g., a point mutation or short tag). Flank this edit with homology arms of 30-40 nucleotides on each side, homologous to the sequence surrounding the target site.

- Complex RNP with Donor: Form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex by pre-incubating purified Cas9 protein with your target-specific sgRNA.

- Co-Deliver into Cells: Co-transfect the RNP complex together with the ssDNA donor into your target cells. For mammalian cells, this can be done via electroporation or lipofection.

- Harvest and Extract DNA: Incubate cells for 48-72 hours to allow for repair, then harvest the cells and extract genomic DNA.

- Analyze Editing Efficiency: Amplify the target genomic region by PCR and analyze the editing outcomes using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify the percentage of HDR versus indels.

Protocol 2: Enhancing HDR Using a Modular ssDNA Donor

This protocol details the use of RAD51-preferred sequences to boost HDR, as described in [28].

- Design Modular ssDNA Donor: Synthesize your ssDNA donor with the desired edit and standard homology arms. Incorporate a RAD51-preferred sequence motif (e.g., 5'-TCCCC-3') at the 5' end of the donor molecule, as the 5' end is more tolerant of such additions.

- Prepare Editing Components: Complex high-fidelity Cas9 protein with your sgRNA to form an RNP.

- Transfect and Inhibit NHEJ: Co-deliver the RNP and the modular ssDNA donor into your cells. To maximize HDR, treat the cells with a small-molecule NHEJ inhibitor (e.g., M3814) or employ the HDRobust strategy (combined inhibition of NHEJ and MMEJ) [29].

- Validate HDR Efficiency: After 72 hours, analyze the cells using flow cytometry (if using a fluorescent reporter) or NGS to quantify precise gene editing. This combination has achieved median HDR efficiencies of ~75% in human cells [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HDR Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function in HDR Optimization |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex | Delivers the nuclease activity directly, leading to faster editing and reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid delivery. |

| 5'-Biotin or 5'-C3 Modified Donors | Chemical modifications that tether the donor to Cas9 (biotin) or prevent concatemerization (C3), improving single-copy HDR integration [5]. |

| RAD51-Preferred Sequence Modules | Functional DNA sequences engineered into the donor to recruit endogenous RAD51, enhancing donor recruitment to the break site without chemical modification [28]. |

| NHEJ/MMEJ Inhibitors (e.g., M3814) | Small molecules that transiently inhibit the competing error-prone repair pathways, thereby favoring HDR [29]. |

| HDRobust Substance Mix | A defined mixture that simultaneously inhibits NHEJ and MMEJ, drastically increasing outcome purity by directing most repairs through HDR [29]. |

Visualizing the Strategies and Pathways

The following diagrams summarize the key strategies for optimizing ssDNA donors and the cellular repair pathways involved.

In CRISPR-mediated genome editing, the precise incorporation of desired sequences via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) competes with the dominant and error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway. A powerful strategy to shift this balance is the use of small molecule inhibitors that target key proteins in the NHEJ machinery, particularly the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). This guide provides a technical overview and troubleshooting resource for using these chemical boosters to enhance HDR efficiency in your research.

FAQ: Understanding DNA-PKcs Inhibitors

Q1: What is the core mechanism by which DNA-PKcs inhibitors enhance HDR? DNA-PKcs is a critical serine/threonine kinase in the NHEJ pathway. The NHEJ repair process is initiated when the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer binds to broken DNA ends, subsequently recruiting DNA-PKcs to form the DNA-PK holoenzyme [31] [32]. This enzyme acts as a scaffold, tethering the broken ends together and facilitating their ligation [31]. By inhibiting DNA-PKcs, you pharmacologically suppress the competing NHEJ pathway, thereby creating a cellular environment that is more permissive for the HDR machinery to use your provided donor template [32].

Q2: What are the commonly used DNA-PKcs inhibitors and their reported efficacies? Researchers employ several small molecule inhibitors. The table below summarizes key compounds and their performance in recent studies.

Table 1: Key Small Molecule DNA-PKcs Inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Reported Effect on HDR/NHEJ | Key Findings and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| AZD7648 | Significantly increases apparent HDR reads in short-read sequencing [33]. | Can cause frequent kilobase- and megabase-scale deletions, chromosome arm loss, and translocations. These large-scale alterations often evade detection by standard short-read NGS assays [33]. |

| NU7026 | Potent and selective inhibitor; suppresses NHEJ [32]. | Shown to prevent CRISPR/Cas9-mediated degradation of HBV cccDNA, leading to frequent on-target deletions. Has ~60-fold higher activity for DNA-PK over PI3K [32]. |

| NU7441 | Drastically reduces NHEJ frequency while increasing HR rates [32]. | Cited as a potent DNA-PKcs inhibitor used in research settings. |

Q3: What are the major pitfalls and how can I detect them? A significant challenge is the potential for on-target genomic instability that is not captured by conventional analysis methods.

- Problem: The inhibitor AZD7648, while boosting HDR reads in short-read sequencing, was found to concurrently increase the frequency of large-scale chromosomal alterations [33].

- Solution: Implement comprehensive genotyping strategies that go beyond short-range PCR and short-read sequencing.

- Long-Range PCR & Long-Read Sequencing (Nanopore): Essential for detecting kilobase-scale deletions [33].

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): Useful for quantifying copy number variations and gene loss [33].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Can reveal coherent blocks of gene expression loss indicative of large-scale chromosomal aberrations [33].

Q4: Are there alternative or complementary strategies to small molecule inhibitors? Yes, other methods focus on directly enhancing the HDR pathway itself rather than suppressing its competition.

- Protein Engineering: Supplementing with RAD52 protein was shown to increase single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) integration efficiency nearly 4-fold, though it was accompanied by higher template multiplication [5].

- Donor DNA Optimization: Engineering ssDNA donors to include "HDR-boosting modules" with sequences preferred by the HDR protein RAD51 can significantly enhance HDR efficiency without chemical modifications [21]. Modifying the 5' ends of donor DNA with biotin or a C3 spacer can also boost single-copy integration [5].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Enhancing HDR using DNA-PKcs Inhibitors in Cell Culture

This protocol outlines the key steps for using inhibitors like AZD7648 or NU7026 in conjunction with CRISPR-Cas9 editing.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitor (e.g., AZD7648) | Selective small molecule that inhibits the kinase activity of DNA-PKcs, suppressing the NHEJ pathway. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex | The gene-editing machinery; a ribonucleoprotein complex that creates a specific double-strand break. |

| HDR Donor Template | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) containing the desired edit flanked by homology arms. |

| Long-Range PCR Kit | For amplifying large fragments around the target site to assess large-scale deletions. |

| ddPCR/scRNA-seq Tools | For in-depth analysis of potential large-scale genomic alterations. |

Workflow:

- Cell Preparation: Seed your target cells (e.g., HEK293T, iPSCs, primary CD34+ HSPCs) at an appropriate density.

- Transfection/Nucleofection: Deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 RNP complex along with your HDR donor template into the cells.

- Inhibitor Treatment: Add the chosen DNA-PKcs inhibitor (e.g., 1 µM AZD7648) to the culture media immediately after or during the delivery step. Include a DMSO-only control.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for the duration recommended for the specific inhibitor (e.g., 24-72 hours for AZD7648).

- Analysis:

- Primary Screening: Use short-read NGS of a target amplicon to get an initial readout of HDR and indel efficiency.

- Comprehensive Genotyping: To rule out large-scale alterations, perform long-range PCR followed by long-read sequencing (e.g., ONT) and/or ddPCR on edited samples, especially those treated with the inhibitor [33].

Protocol: Optimizing ssDNA Donors with RAD51-Boosting Modules

As an alternative or complementary strategy to chemical inhibition, you can optimize your donor design.

Workflow:

- Design: Synthesize your ssDNA donor with the HDR-boosting sequence module (e.g., the "TCCCC"-containing SSO9 or SSO14 motif [21]) incorporated at its 5' end. The 5' end is generally more tolerant of such additions than the 3' end [21].

- Delivery: Co-deliver the modified ssDNA donor with your CRISPR-Cas9 system.

- Combination Therapy: For maximal HDR, combine the optimized donor with an NHEJ inhibitor (e.g., M3814) or use the HDRobust strategy, which has been shown to achieve HDR efficiencies up to 90% [21].

Pathway and Mechanism Visualization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary mechanistic role of RAD52 in improving HDR efficiency? RAD52 is a key protein in the homologous recombination (HR) pathway. It directly binds to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and facilitates the central step in HDR: the invasion of the ssDNA donor template into the homologous genomic region after a double-strand break. Co-expressing RAD52 with the CRISPR-Cas9 system increases the local concentration of the repair machinery and donor template at the cleavage site, thus promoting precise editing over error-prone repair pathways [19].

Q2: I am using a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donor. Should I use a RAD52 fusion protein or co-express it separately? Both strategies are effective, but they have different considerations. Research shows that a Rad52-Cas9 fusion protein can be particularly effective, as it physically recruits the HDR-enhancing factor directly to the site of the DNA break [19]. However, co-expression of non-fused RAD52 also significantly boosts HDR. For ssDNA donors, studies have shown that supplementing with RAD52 protein can increase precise integration by nearly 4-fold, though this can be accompanied by a higher rate of template multiplication (concatemer formation) [5].

Q3: What are the trade-offs of using RAD52 to enhance HDR? The primary trade-off is an increased risk of unwanted template integration events. While RAD52 can dramatically boost precise HDR rates, it can also lead to a higher frequency of head-to-tail multicopy insertions of the donor template into the genome [5]. It is crucial to design your screening strategy to distinguish between single-copy correct integrations and these concatemers.

Q4: Besides RAD52, what other strategies can I combine for a synergistic HDR boost? A multi-faceted approach is often most successful. You can combine RAD52 with:

- Donor DNA Modifications: Using 5′-end modified donors (e.g., 5′-biotin or 5′-C3 spacer) can further enhance single-copy HDR efficiency, with 5′-C3 spacers showing up to a 20-fold increase in some studies [5].

- HDR-Boosting Modules: Engineering ssDNA donors to include specific sequence motifs (like RAD51-preferred binding sequences) can augment affinity for endogenous repair proteins and improve HDR efficiency without chemical modifications [21].

- NHEJ Inhibition: Using small molecules to suppress the non-homologous end joining pathway can help shift the repair balance toward HDR, but caution is advised as some inhibitors can exacerbate large-scale genomic aberrations [34].

Q5: My HDR efficiency is still low after using RAD52. What should I troubleshoot? First, verify the quality and design of your donor template. Using denatured, long double-stranded DNA templates has been shown to boost precision and reduce concatemer formation compared to standard dsDNA [5]. Second, ensure your donor has sufficient homology arm lengths. Finally, confirm the efficiency of your delivery method for both the CRISPR components and the RAD52 protein/mRNA to ensure they are co-localized in the same cells.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low HDR Efficiency Despite RAD52 Expression

| Possible Cause | Symptoms | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient delivery of RAD52 | Low protein expression confirmed by Western blot; no improvement over baseline. | Optimize delivery method (e.g., mRNA co-electroporation, protein delivery); use a fluorescence reporter to confirm co-delivery. |

| Suboptimal donor template design | High rates of indels (NHEJ) but no precise integration. | Use single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors; extend homology arms; consider 5′-end modifications (biotin/C3 spacer) [5] [21]. |

| Dominant NHEJ pathway | High indel frequency even with RAD52 present. | Consider low-toxicity, small molecule NHEJ inhibitors (e.g., Scr7), but thoroughly validate genomic integrity afterward [34] [19]. |

| Target site inaccessibility | Low overall editing efficiency (low indels and HDR). | Re-design gRNA to target a more accessible chromatin region; screen multiple gRNAs. |

Problem: High Rates of Unwanted Multi-Copy Donor Insertions

| Possible Cause | Symptoms | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High concentration of donor template | PCR screening shows larger-than-expected amplicons; Southern blot confirms concatemers. | Titrate the donor DNA to the lowest effective concentration. |

| Use of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donors | Frequent head-to-tail template multiplications. | Switch to denatured dsDNA or single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors, which reduce this issue [5]. |

| RAD52 activity | Increased HDR is accompanied by a rise in template multiplication. | This is a known trade-off with RAD52 [5]. Combine RAD52 with 5′-C3 spacer or 5′-biotin-modified donors, which are proven to reduce multiplications and boost single-copy integration. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on RAD52 and related HDR-enhancing strategies in mouse zygotes and cell models.

Table 1: Efficiency of HDR Enhancement Strategies

| Strategy | Test System | HDR Efficiency (Control) | HDR Efficiency (Enhanced) | Fold Increase | Key Observation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAD52 Supplementation (with denatured DNA) | Mouse zygotes | 8% (ssDNA only) | 26% | ~3.3 fold | Increased template multiplication to 30% | [5] |

| 5′-C3 Spacer (on dsDNA) | Mouse zygotes | Not specified (baseline) | 40% | Up to 20-fold vs. baseline | Significant boost regardless of donor strandness | [5] |

| 5′-Biotin Modification (on dsDNA) | Mouse zygotes | Not specified (baseline) | 14% | Up to 8-fold vs. baseline | Improved single-copy integration | [5] |

| HDR-Boosting Modules (RAD51 sequences in ssDNA) | Human cells (HEK293T) | Varies by locus | 66.62% - 90.03% (when combined with NHEJi) | Significant | Chemical modification-free strategy | [21] |

Detailed Protocol: Enhancing HDR with a RAD52-Cas9 Fusion Strategy

This protocol is adapted from research demonstrating enhanced HDR using a fusion protein strategy in mammalian cells [19].

Objective: To perform precise genome editing by co-delivering a Cas9 nuclease fused with RAD52 and an ssDNA donor template.

Materials:

- Plasmids: Expression vector for the RAD52-Cas9 fusion protein (e.g., pCBh-RAD52-Cas9), and a U6-sgRNA expression vector.

- Donor Template: Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligo with homologous arms (90-100 nt total is common) and the desired edit.

- Cells: Adherent mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T).

- Transfection Reagent: PEI or a commercial lipofectamine-based reagent.

- Analysis Reagents: Lysis buffer, PCR reagents, T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor nuclease for indel analysis, sequencing primers.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Method:

- Construct Cloning: Clone your target-specific sgRNA sequence into a U6-driven expression vector. Obtain or clone a RAD52-Cas9 fusion construct where the RAD52 gene is fused to the Cas9 gene, typically with a flexible linker.

- Donor Design: Design a single-stranded DNA donor oligo with the desired sequence change flanked by homology arms (30-50 nt each). The 5′ end is more tolerant of additional sequence modules if needed [21].

- Cell Transfection: Seed HEK293T cells to reach 70-80% confluency at transfection. Co-transfect the cells with:

- RAD52-Cas9 fusion plasmid (e.g., 500 ng)

- sgRNA plasmid (e.g., 250 ng)

- ssDNA donor oligo (e.g., 100-200 pmol)

- Use an appropriate transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Incubation: Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-transfection for genomic DNA extraction and downstream analysis.

- Analysis:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from transfected cells.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the targeted genomic region.

- HDR Efficiency Quantification: Use a combination of methods:

- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP): If the edit introduces or disrupts a restriction site.

- TIDE/TIDER Decomposition Assay: For quantifying HDR and NHEJ frequencies from Sanger sequencing data.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For the most accurate and comprehensive analysis of editing outcomes, including precise HDR, indels, and unwanted genomic alterations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for RAD52 HDR Enhancement Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Example & Note |

|---|---|---|

| RAD52 Expression Vector | Provides source of RAD52 protein. | pCBh-RAD52 (for co-expression); pCBh-RAD52-Cas9 (for fusion) [19]. |

| HDR-Enhancing ssDNA Donor | Template for precise repair. | Chemically synthesized ssDNA with 5′ modifications (biotin, C3 spacer) or "HDR-boosting" RAD51-binding sequence modules [5] [21]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitor | Shifts repair balance toward HDR. | Scr7 (DNA Ligase IV inhibitor). Caution: Some DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) can cause severe structural variations [34]. |

| Commercial HDR Enhancer | Optimized, proprietary solutions. | Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein (IDT); a recombinant protein that boosts HDR with no reported increase in off-target edits [23]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | Reduces off-target cleavage. | SpCas9-HF1 or eSpCas9(1.1) variants. Use when high specificity is critical. |

Safety and Optimization Notes

When implementing HDR-enhancing strategies, it is critical to be aware of broader genomic impacts. Recent studies highlight that some methods, particularly the use of certain DNA-PKcs inhibitors to promote HDR, can lead to unforeseen large-scale structural variations (SVs), including megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations, which may be missed by standard short-read sequencing [34]. Always employ comprehensive genomic integrity assays (e.g., CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS) when developing therapeutic approaches.

FAQ: Understanding 5′ Modifications for HDR

What is the primary function of 5′ modifications on dsDNA donor templates? The primary function is to shield the ends of long double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donors. This shielding prevents the donors from joining together end-to-end (multimerization) and integrating as concatemers, which is a common problem with unmodified linear dsDNA. By promoting a monomeric donor conformation, 5′ modifications favor precise, single-copy integration via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [5] [35].

How do 5′-biotin and 5′-C3 spacer modifications directly improve HDR outcomes? These modifications directly enhance the efficiency of precise, single-copy integration. Research shows that 5′-biotin can increase single-copy HDR integration by up to 8-fold, while the 5′-C3 spacer modification can produce a remarkable up to 20-fold rise in correctly edited animal models compared to unmodified donors [5].

What are the practical consequences of using modified versus unmodified donors? The table below summarizes the key differences observed in a study targeting the Nup93 locus in mouse models [5].

| Donor DNA Type | 5′ End Modification | HDR Efficiency (%) | Template Multiplication (Head-to-Tail Integration %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dsDNA | Unmodified (5'-P) | 2% | 34% |

| dsDNA (denatured) | Unmodified (5'-P) | 8% | 17% |

| dsDNA | 5'-C3 Spacer | 40% | 9% |

| dsDNA | 5'-Biotin | 14% | 5% |

In which experimental scenarios are these modifications most critical? These modifications are particularly beneficial when integrating long dsDNA templates, such as those containing fluorescent reporters or conditional knockout elements like LoxP sites, where single-copy, precise integration is required. They are a practical strategy to enhance HDR without directly interfering with the cellular DNA repair machinery [5] [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Low HDR Efficiency and High Rates of Unwanted Template Multiplication

Symptoms:

- Genotyping reveals a high proportion of founders with head-to-tail multi-copy insertions of the donor template.

- Very low yield of founders with precise, single-copy HDR events.

- Difficulty in obtaining cleanly edited cell lines or animal models.

Solutions:

- Implement 5′-End Modifications: Switch from unmodified dsDNA donors to those with 5′-biotin or 5′-C3 spacer modifications. These "bulky" moieties sterically hinder the ends of the DNA, preventing concatemer formation and favoring single-copy HDR [5] [35].

- Combine with Denaturation: For unmodified or 5'-monophosphorylated (5'-P) dsDNA, heat denaturation into single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) can also boost precision and reduce template multiplication, though the effect is less potent than chemical modification [5].

- Consider RAD52 Supplementation Cautiously: Adding human RAD52 protein to the injection mix with ssDNA can increase HDR efficiency (e.g., from 8% to 26% in one study). However, this gain may come with a significant trade-off of increased template multiplication (e.g., from 17% to 30%) [5].

Problem: High Embryonic Lethality Post-Microinjection

Symptoms:

- A significant drop in the survival rates of injected embryos, making it impossible to generate founders.

Solutions:

- Avoid Certain Modifications: Some modifications, like 5′-Amino-dT (A-dT), have been associated with high embryonic lethality in model organisms like medaka fish. If encountering toxicity, switch to better-tolerated modifications like 5′-biotin or 5′-C3 spacer [35].

- Optimize Concentration: Titrate the concentration of the CRISPR-Cas9 components (Cas9 mRNA, sgRNA) and the modified donor DNA to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [36].

Experimental Protocol: Utilizing 5′ Modified Donors

This protocol outlines the key steps for using 5' modified long dsDNA donors in CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knock-in experiments, based on methodologies from recent publications [5] [35].

1. Design and Synthesis of the Donor Template

- Homology Arms: Design a donor cassette with homology arms flanking your insert (e.g., a fluorescent protein or LoxP sites). For long dsDNA donors, arms of 400-500 bp are typical.

- PCR Amplification with Modified Primers: Amplify your donor cassette using a high-fidelity PCR system. The critical step is to use primers where the 5′ end is synthesized with a biotin or C3 spacer (propyl) modification. Standard desalting purification of primers is often sufficient.

- Purification: Purify the final PCR product to remove enzymes, salts, and unused nucleotides.

2. Preparation of the CRISPR-Cas9 Injection Mix

- Combine the following components in microinjection buffer:

- Cas9: Cas9 mRNA or protein at an optimized concentration.

- sgRNA: One or more sgRNAs targeting the genomic locus of interest.

- Modified Donor DNA: The purified, 5′ modified dsDNA donor template.

- Optional: RAD52 protein can be added to boost HDR but monitor for increased multimerization.

3. Microinjection and Embryo Transfer

- Perform standard microinjection procedures for your model organism (e.g., into the pronucleus of zygotes).

- Transfer the injected embryos into pseudopregnant foster females to develop to term.

4. Genotyping and Analysis of Founders (F0)

- Screen born founders for the desired edit using a combination of methods:

- Junction PCR: Use primers outside the homology arms and within the inserted sequence to identify precise HDR events.

- Southern Blotting: This is the gold standard for confirming single-copy integration and ruling out concatemers.

- Sequencing: Always sequence the modified locus to verify perfect integration without errors.

Mechanism of Action: How 5' Modifications Facilitate Single-Copy HDR

The following diagram illustrates the mechanism by which 5' modified donor templates prevent multimerization and promote precise single-copy integration.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their functions for implementing this advanced HDR enhancement strategy.

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 5'-Biotin Modified Primers | Chemically synthesizes donor DNA with 5' biotin modification to block end-joining. | Standard desalting purification is often sufficient. [5] [35] |

| 5'-C3 Spacer (Propyl) Modified Primers | Chemically synthesizes donor DNA with an inert carbon spacer to block end-joining. | Can show higher efficiency gains than biotin in some systems. [5] [35] |

| RAD52 Protein | Recombinant protein added to injection mix to enhance HDR efficiency, particularly for ssDNA. | Can increase rates of unwanted template multiplication; use requires optimization. [5] |

| Long dsDNA Donor Template | PCR-amplified DNA cassette containing the insert (e.g., GFP, LoxP) flanked by homology arms. | Homology arm length (e.g., 400-500 bp) and sequence are critical for HDR efficiency. [5] [35] |

In CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair (HDR), the precise integration of donor DNA templates is a cornerstone for generating advanced animal models and therapeutic knock-ins. A significant obstacle in this process is the formation of concatemers—unwanted multi-copy integrations of the donor template arranged in head-to-tail tandem repeats [5] [37]. These concatemers arise when linear double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donor templates undergo non-homologous integration via the cell's error-prone repair pathways, leading to inaccurate editing outcomes, disrupted transgene expression, and complicating the genotyping of correctly modified cells [5] [38].

Template denaturation, the process of applying heat to separate dsDNA into single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), presents a powerful strategy to mitigate this issue. This article explores the molecular basis of how heat-denatured dsDNA reduces concatemer formation and enhances the precision of HDR, providing a practical troubleshooting guide for researchers aiming to optimize their genome editing experiments.

The Mechanism: Why Denatured Templates Reduce Concatemers

The structure of the DNA donor template directly influences its interaction with the cellular DNA repair machinery. The propensity for linear dsDNA to form concatemers is largely due to its exposed double-stranded ends, which are susceptible to recognition and ligation by the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway [38].

The Molecular Basis of Concatemer Formation

- DSB Repair Pathway Competition: When a CRISPR-induced double-strand break (DSB) is introduced, it triggers a competition between the high-fidelity HDR pathway and the error-prone NHEJ pathway [38]. NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle and often dominates, especially in non-dividing cells.

- Ligation of Exogenous DNA Ends: The free ends of linear dsDNA donors can be recognized by the NHEJ machinery as substrates for direct ligation. This can result in the donor template integrating into the target site—or even off-target sites—in a homology-independent manner [38] [39]. When multiple copies of the donor template ligate together before integration, a concatemer is formed [5].

How Single-Stranded DNA Avoids This Pitfall

Heat denaturation converts dsDNA into ssDNA, which fundamentally alters how the cell processes the donor template.

- Elimination of NHEJ Substrates: Single-stranded DNA lacks double-stranded ends, thereby removing the primary substrate for the NHEJ machinery. This inherently redirects the repair process toward single-strand annealing and HDR-like pathways that utilize homologous sequences [5] [3].

- Enhanced Incorporation Fidelity: Research indicates that ssDNA donors are processed differently, favoring homology-based integration over random end-joining. This leads to a higher proportion of precisely edited alleles and a marked reduction in head-to-tail multiplications [5].

The following diagram illustrates the divergent cellular repair pathways for double-stranded and single-stranded DNA donors, leading to their distinct editing outcomes.

Diagram: Differential repair pathways for dsDNA and ssDNA donors. dsDNA donors with exposed ends are susceptible to NHEJ, leading to concatemer formation. ssDNA donors, lacking these ends, are channeled toward HDR, resulting in precise, single-copy integration.

Key Experimental Evidence & Data

The effectiveness of template denaturation is supported by robust quantitative data. A seminal study targeting the Nup93 locus in mouse zygotes provided a direct comparison of editing outcomes using dsDNA versus heat-denatured ssDNA templates [5].

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes

The table below summarizes the critical findings from the Nup93 locus study, demonstrating the impact of template denaturation on HDR precision and concatemer formation.

| Template Type | Total Pups Born | Correctly Targeted (HDR%) | Head-to-Tail Multiplication (HtT%) | Locus Modification % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dsDNA (5'-P) | 47 | 1 (2%) | 16 (34%) | 40% |

| dsDNA Denatured (5'-P) | 12 | 1 (8%) | 2 (17%) | 50% |

| Denatured + RAD52 | 23 | 6 (26%) | 7 (30%) | 83% |

Table: Impact of template denaturation on HDR efficiency and concatemer formation at the Nup93 locus. Data adapted from [5].

Interpretation of Experimental Data

- Boost in Precision: Denaturing the dsDNA template led to a 4-fold increase in the rate of precise HDR (from 2% to 8%), confirming that ssDNA is a more efficient substrate for precise editing [5].

- Reduction in Concatemers: More strikingly, denaturation caused an almost 2-fold reduction in head-to-tail template multiplication (from 34% to 17%), directly demonstrating its efficacy in suppressing concatemerization [5].

- The Trade-off with RAD52: Supplementing the denatured template with the RAD52 protein, a recombinase enhancer, further increased HDR efficiency to 26% but also increased template multiplication to 30% [5]. This highlights a potential trade-off, where aggressively boosting HDR can re-introduce the risk of concatemers.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

To successfully implement this strategy, follow this detailed protocol for template preparation and microinjection, derived from the methodology that yielded the above data [5].

Donor Template Design and Preparation

- Template Design: Design a dsDNA donor template (e.g., ~600 bp for conditional knockout models) containing your gene of interest flanked by homology arms (60-100 nt is sufficient) and the necessary site-specific recombinase sites (e.g., LoxP) [5].

- 5' End Modification (Optional but Recommended): Synthesize the template with 5'-monophosphates (5'-P) or other modifications like 5'-biotin or 5'-C3 spacer, which have been shown to further boost single-copy HDR integration [5].

- Heat Denaturation:

- Prepare the dsDNA template in nuclease-free buffer. Incubate at 95°C for 5 minutes to ensure complete strand separation.

- Immediately transfer the tube to ice for at least 2 minutes to prevent reannealing. The template is now ready for use as ssDNA.

Microinjection Mix Preparation and Zygote Injection

- Prepare the RNP Complex: Complex the Cas9 protein with crRNAs (designed to target the flanking regions of your genomic locus) to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) [5].

- Assemble the Injection Mix: Combine the following components:

- Pre-complexed CRISPR-Cas9 RNP.

- Freshly denatured ssDNA donor template (from Step 1.3).

- (Optional) RAD52 protein (e.g., 100-200 ng/µL). Note: This may increase HDR but also concatemer risk [5].

- Perform Microinjection: Inject the mixture directly into the pronucleus or cytoplasm of mouse zygotes using standard microinjection techniques [5].

- Embryo Transfer and Genotyping: Transfer viable injected embryos into pseudopregnant female mice. Analyze the resulting founder animals (F0) using junction PCR, Southern blotting, or long-read sequencing to accurately determine integration patterns and identify precise HDR events [5] [37].

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My HDR efficiency remains low even after using denatured templates. What can I optimize further?

- A: Investigate the following factors:

- 5' End Modifications: Using 5'-biotin or a 5'-C3 spacer on your donor DNA can dramatically improve single-copy integration. One study showed a 20-fold rise in correctly edited mice with a 5'-C3 spacer modification [5].

- Homology Arm Length: While ssDNA works with short arms, ensure they are long enough (e.g., 90-100 nt) for efficient strand invasion and pairing [40].

- crRNA Design: Targeting the antisense strand with your crRNAs has been shown to improve HDR precision in some contexts [5].

Q2: Are there any cell types or contexts where ssDNA donors are not superior to dsDNA?

- A: Yes, performance can be system-dependent. One study in human diploid RPE1 and HCT116 cells found that for long transgene insertions (like fluorescent reporters), dsDNA donors actually outperformed ssDNA in both efficiency and the ratio of precise insertion [40]. Always validate the optimal donor type for your specific cell line and application.

Q3: I am concerned about large-scale unintended edits. How can I thoroughly screen for them?

- A: This is a critical safety consideration. Conventional short-read sequencing can miss large deletions and rearrangements [33] [34].

- Employ Long-Read Sequencing: Use technologies like Oxford Nanopore (ONT) or PacBio to sequence long-range PCR amplicons spanning the entire integration site. This can reveal kilobase-scale deletions, concatemers, and integration of vector sequences (e.g., AAV ITRs) that are otherwise invisible [33] [37].

- Avoid Aggressive NHEJ Inhibition: While inhibitors like AZD7648 can boost HDR rates, they are also associated with a significant increase in large-scale chromosomal alterations, including megabase-scale deletions and chromosome arm loss [33] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 5'-C3 Spacer / 5'-Biotin | Chemical modifications to donor DNA 5' ends that block illegitimate ligation and improve HDR. | Increased single-copy HDR integration by up to 20-fold in mouse models [5]. |

| Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks (IDT) | Chemically modified, sequence-verified dsDNA donors designed for high HDR and low non-homologous integration. | A commercial source of optimized dsDNA donors for knock-in experiments [39]. |

| RAD52 Protein | Recombinase that promotes strand invasion and exchange during homologous recombination. | Enhanced ssDNA integration nearly 4-fold, though with increased template multiplication in zygotes [5]. |

| Long-Range PCR & ONT Sequencing | Critical quality control method to detect concatemers, large deletions, and complex rearrangements. | Identified kilobase-scale deletions and partial AAV vector integrations in founder mice [33] [37]. |

| enGager / TESOGENASE System | Cas9 fused to ssDNA-binding peptides to tether cssDNA donors, increasing local concentration and HDR. | Achieved high-efficiency CAR transgene integration (33%) in primary human T cells [41]. |