CRISPR Screening in Functional Genomics: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Clinical Translation

CRISPR screening has emerged as a transformative technology in functional genomics, enabling systematic interrogation of gene function across diverse biological contexts.

CRISPR Screening in Functional Genomics: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Clinical Translation

Abstract

CRISPR screening has emerged as a transformative technology in functional genomics, enabling systematic interrogation of gene function across diverse biological contexts. This comprehensive review explores the foundational principles of CRISPR screening, detailing its evolution from a basic gene-editing tool to a sophisticated platform for high-throughput genetic analysis. We examine current methodological approaches including knockout, activation, and inhibition screens, along with cutting-edge applications in drug target identification, personalized medicine, and complex disease modeling. The article provides practical troubleshooting guidance for common experimental challenges and data analysis pitfalls. Finally, we evaluate validation frameworks and comparative performance against alternative technologies, highlighting the rapid clinical translation of CRISPR-based discoveries and future directions integrating artificial intelligence and single-cell technologies. This resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with both theoretical knowledge and practical insights to leverage CRISPR screening in their functional genomics programs.

The CRISPR Screening Revolution: Redefining Functional Genomics

CRISPR screening has evolved from a basic gene-editing tool into a powerful framework for high-throughput functional genomics research. The integration of CRISPR-based functional genomics with pluripotent stem cell (PSC) technologies represents a transformative approach for investigating gene function, modeling human disease, and advancing regenerative medicine [1]. This evolution has been marked by the development of sophisticated CRISPR-Cas platforms including gene knockouts, base and prime editing, and CRISPR activation or interference (CRISPRa/i) systems applied to diverse biological models [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances provide unprecedented capability to systematically dissect complex biological processes and identify novel therapeutic targets through high-content screening methodologies.

The core innovation lies in moving beyond single-gene manipulation to genome-scale interrogation of gene function. While early CRISPR-Cas9 systems enabled targeted gene disruption through double-strand breaks repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), newer platforms have expanded this toolbox significantly [2]. Current technologies now include catalytically deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional regulators for gene activation or repression without altering DNA sequence, base editors for precise single-nucleotide changes, and prime editors that offer search-and-replace functionality without double-strand breaks [2] [3]. These tools have opened new avenues for comprehensive genotype-phenotype mapping in diverse cellular contexts.

Technological Evolution of CRISPR Screening Platforms

Advanced Screening Methodologies

Recent methodological innovations have substantially improved the resolution and applicability of CRISPR screening in complex model systems. The CRISPR-StAR (Stochastic Activation by Recombination) platform addresses key limitations in conventional screening by introducing internal controls generated through Cre-inducible sgRNA expression [4]. This method activates sgRNAs in only half the progeny of each cell after clonal expansion, creating intrinsic controls that overcome heterogeneity and genetic drift in bottleneck scenarios such as in vivo tumor modeling [4]. The system employs intercalated lox5171 sites (incompatible with loxP) to create mutually exclusive recombination outcomes—either excision of a stop cassette to generate active sgRNAs or excision of the tracrRNA to maintain inactive states [4]. This internal control mechanism maintains high reproducibility (Pearson correlation coefficient >0.68) even at low sgRNA coverage where conventional analysis fails completely [4].

For high-content phenotypic screening, the PERISCOPE (perturbation effect readout in situ with single-cell optical phenotyping) platform combines destainable high-dimensional phenotyping based on Cell Painting with optical sequencing of molecular barcodes [5]. This approach enables genome-scale morphological profiling through five-color fluorescence microscopy imaging cell compartments (actin, mitochondria, Golgi, endoplasmic reticulum, and nucleus) followed by in situ sequencing to assign perturbations [5]. A key innovation involves conjugating phenotypic probes to fluorophores using disulfide linkers that can be cleaved with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) after imaging, freeing fluorescent channels for subsequent barcode sequencing [5]. This technology has generated the first morphology-based genome-wide perturbation atlas, profiling >20,000 gene knockouts in >30 million human cells [5].

Algorithmic and Library Design Improvements

Substantial progress has been made in sgRNA library design and performance optimization. Benchmark comparisons of CRISPRn guide-RNA design algorithms have demonstrated that smaller, more optimized libraries can perform equivalently or superior to larger conventional libraries [6]. The Vienna library, designed using VBC scores, achieves strong depletion of essential genes with only 3 guides per gene, outperforming the 6-guide Yusa v3 library in both essentiality and drug-gene interaction screens [6]. Dual-targeting libraries, where two sgRNAs target the same gene, show enhanced depletion of essential genes but may trigger a heightened DNA damage response, as evidenced by a log₂-fold change delta of -0.9 compared to single-targeting guides [6].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPR sgRNA Libraries

| Library Name | Guides per Gene | Essential Gene Depletion | Drug-Gene Interaction Performance | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna-single | 3 | Strongest depletion | Best resistance log fold changes | Selected by VBC scores |

| Vienna-dual | 3 pairs | Strong depletion | Strongest effect sizes | Dual targeting strategy |

| Yusa v3 | 6 | Weaker depletion | Consistently lowest performance | Conventional library |

| MinLib | 2 | Strong depletion | Not tested | Minimal guide design |

| Brunello | 4 | Intermediate | Not tested | Widely adopted |

Artificial intelligence has further advanced library design and editor optimization. Machine learning and deep learning models now accelerate the optimization of gene editors for diverse targets, guide the engineering of existing tools, and support the discovery of novel genome-editing enzymes [3]. AI methodologies have been particularly valuable for predicting Cas protein behavior, optimizing guide RNA designs, and forecasting editing outcomes based on sequence and cellular context [3].

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols for Advanced CRISPR Screening

Protocol 1: CRISPRi Screening for Cell-Type-Specific Genetic Dependencies

Background: This protocol describes comparative CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) screening to identify cell-type-specific essential genes, particularly in mRNA translation machinery, across human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and differentiated lineages [7].

Experimental Workflow:

Cell Line Engineering:

sgRNA Library Design and Cloning:

Cell Differentiation and Screening:

- Differentiate inducible hiPS cells into neural progenitor cells (NPCs), neurons, and cardiomyocytes using established protocols [7].

- Transduce inducible hiPS cells, NPCs, and control cells (e.g., HEK293) with lentiviral sgRNA library at low MOI to ensure one sgRNA per cell [7].

- Induce KRAB-dCas9 expression with doxycycline and maintain cultures for ten population doublings [7].

Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Collect genomic DNA from matched samples grown without or with doxycycline [7].

- Amplify and sequence sgRNA regions, then calculate gene-level enrichment/depletion scores using established CRISPRi screen analysis pipelines [7].

- Validate hits by individual sgRNA transduction and RT-qPCR confirmation of knockdown efficiency [7].

Key Considerations: CRISPRi avoids p53-mediated toxicity associated with double-strand breaks, making it suitable for sensitive pluripotent stem cells [7]. Essentiality profiles differ significantly across cell types; hiPS cells show higher sensitivity to mRNA translation perturbations (76% of targeted genes essential) compared to NPCs (67% essential) [7].

Protocol 2: In Vivo CRISPR Screening Using CRISPR-StAR

Background: This protocol enables high-resolution genetic screening in complex in vivo models by incorporating internal controls to overcome heterogeneity and bottleneck effects [4].

Experimental Workflow:

Vector Construction:

Cell Preparation and Transplantation:

Induction and Analysis:

- Upon tumor establishment (typically 2-3 weeks), induce Cre::ERT2 recombinase with 4-OH tamoxifen administration [4].

- Allow tumor growth for additional 2-3 weeks before harvest [4].

- Quantify abundance of active and inactive sgRNAs within each clonal UMI population using NGS [4].

- Compare representation of active sgRNAs at endpoint to inactive internal UMI controls rather than pre-injection baseline [4].

Key Considerations: CRISPR-StAR maintains high reproducibility (R>0.68) even at low sgRNA coverage where conventional screening fails [4]. The internal control structure corrects for both intrinsic and extrinsic heterogeneity in tumor microenvironment [4].

Protocol 3: Genome-Wide Morphological Profiling with PERISCOPE

Background: This protocol enables unbiased morphology-based genome-wide perturbation mapping through optical pooled screening [5].

Experimental Workflow:

Library Design and Cell Preparation:

- Select ~4 sgRNAs per gene from existing libraries, choosing sequences enabling total deconvolution in 12 cycles of in situ sequencing [5].

- Ensure Levenshtein distance of 2 between sgRNA sequences for error detection [5].

- Clone 80,408 sgRNA library targeting 20,393 genes into CROP-seq vector for direct in situ sequencing of sgRNAs [5].

Cell Staining and Imaging:

- Plate transfected cells and perform five-color Cell Painting: phalloidin (actin), anti-TOMM20 (mitochondria), WGA (Golgi/membrane), ConA (ER), and DAPI (nucleus) [5].

- Image phenotypic markers using high-content microscopy [5].

- Treat with TCEP reducing agent to cleave fluorophores via disulfide linkages [5].

In Situ Sequencing:

Image Analysis and Hit Calling:

- Process images using modified CellProfiler workflow incorporating image alignment and barcode calling [5].

- Extract single-cell morphological profiles using adapted Pycytominer library [5].

- Identify "whole-cell" hit genes based on aggregate signal from all compartments and "compartment" hit genes from subcellular features [5].

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% for hit calling with profile strength calculation using mAP metric [5].

Key Considerations: PERISCOPE profiles >30 million cells generating ~500 cells per gene, enabling detection of subtle morphological phenotypes [5]. Compartment-specific hits reveal subcellular localization of gene function—for example, mitochondrial genes show 54% of phenotypic signal in mitochondrial channel [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced CRISPR Screening

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Effectors | Cas9, Cas12, Cas13, base editors, prime editors | DNA/RNA targeting and modification | Variants with improved specificity (NmeCas9), compact size, altered PAM requirements |

| sgRNA Libraries | Vienna-single, Vienna-dual, Yusa v3, Brunello | High-throughput gene perturbation | Genome-wide coverage, optimized on-target efficiency, minimal off-target effects |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), AAV | Efficient intracellular delivery of editing components | Cell-type specificity, minimal immunogenicity, payload capacity optimization |

| Stem Cell Models | hiPS cells, embryonic stem cells, organoids | Physiologically relevant disease modeling | Differentiation capacity, genetic stability, human disease relevance |

| Screening Platforms | CRISPR-StAR, PERISCOPE, Perturb-seq | High-content phenotypic assessment | Internal controls, single-cell resolution, multi-parameter readouts |

| Analysis Tools | Chronos, MAGeCK, VBC scores, CellProfiler | Data processing and hit identification | Time-series modeling, essentiality calling, morphological feature extraction |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

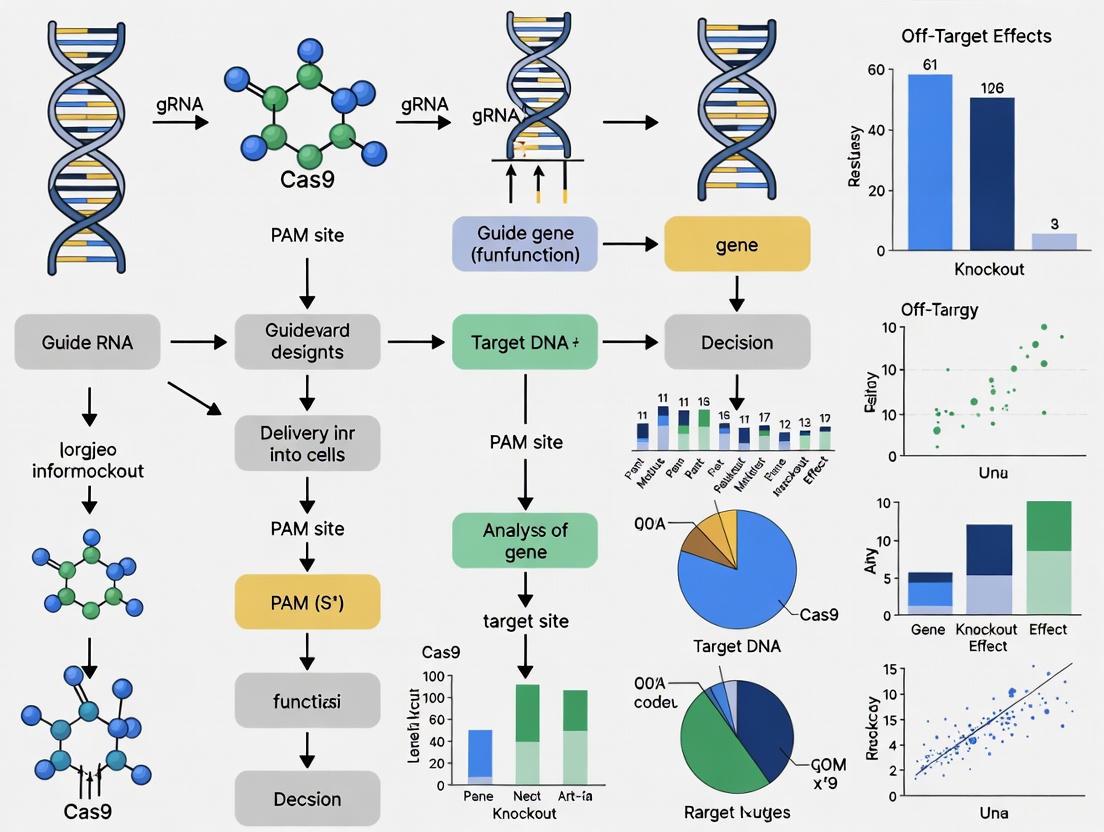

Diagram 1: CRISPR-StAR workflow for in vivo screening. This diagram illustrates the process of stochastic activation by recombination that creates internal controls within each clonal population, enabling high-resolution genetic screening in complex models [4].

Diagram 2: PERISCOPE workflow for morphological profiling. This diagram shows the integrated process of high-content imaging and in situ sequencing that enables genome-wide mapping of gene knockout effects on cell morphology [5].

The evolution of CRISPR screening technologies has transformed functional genomics research, enabling systematic mapping of gene function across diverse biological contexts. Current methodologies now support high-resolution screening in complex models including organoids, in vivo systems, and patient-derived samples through innovations like CRISPR-StAR that overcome previous limitations of heterogeneity and bottleneck effects [4]. The integration of artificial intelligence further accelerates this progress by optimizing editor design, predicting functional outcomes, and discovering novel editing systems [3].

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing single-cell multi-omic readouts, improving in vivo delivery efficiency, and expanding therapeutic applications. The recent success of CRISPR-based medicines like Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia demonstrates the clinical translation potential of these technologies [8]. Additionally, advances in base editing and prime editing offer more precise genetic modification capabilities with reduced off-target effects [3]. As screening methodologies continue to evolve, they will provide increasingly sophisticated tools for deciphering complex biological networks and accelerating drug discovery pipelines.

CRISPR screening has emerged as a powerful tool in functional genomics, enabling researchers to systematically investigate gene function on a genome-wide scale. These screens employ a forward genetics approach, where cellular phenotypes resulting from precise genetic perturbations are analyzed to establish causal relationships between genes and biological processes [9]. The technology has largely surpassed earlier methods like RNA interference (RNAi) due to its higher specificity, fewer off-target effects, and ability to permanently disrupt gene function through DNA editing rather than transient mRNA knockdown [9]. Within drug discovery pipelines, CRISPR screens play a pivotal role in target identification and validation, helping to identify genes associated with diseases and potential therapeutic targets [10] [9]. Two primary experimental paradigms have emerged for conducting these investigations: pooled and arrayed screening platforms, each with distinct methodologies, applications, and considerations.

Fundamental Principles and Direct Comparative Analysis

Pooled Screening Principle

Pooled screens involve introducing a complex mixture of sgRNAs into a single population of cells. A library of sgRNA-containing plasmids is packaged into lentiviral particles and used to transduce host cells at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI), ensuring each cell receives approximately one viral construct [11] [9]. The edited cell population is then subjected to selective pressures or sorted based on a phenotype of interest. Since all genetic perturbations occur within a mixed cell population, linking phenotypes to specific genotypes requires physical separation of cells (e.g., via fluorescence-activated cell sorting or viability selection) followed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify sgRNA enrichment or depletion [11].

Arrayed Screening Principle

Arrayed screens adopt a "one-gene-per-well" approach where individual genetic perturbations are physically separated in multiwell plates [12] [11]. Each well receives a single sgRNA targeting a specific gene, typically delivered as plasmid DNA, viral particles, or pre-complexed ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) [12] [9]. This physical separation enables direct genotype-phenotype linkage without requiring sequencing-based deconvolution. Arrayed screens are compatible with complex multiparametric assays that measure multiple phenotypic endpoints simultaneously, including high-content imaging, morphological analyses, and measurements of secreted factors [12] [9].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Pooled and Arrayed CRISPR Screens

| Characteristic | Pooled Screening | Arrayed Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Organization | Mixed population in a single vessel | Separate wells in multiwell plates |

| Library Delivery | Lentiviral transduction | Transfection or transduction |

| Genotype-Phenotype Linkage | Requires sequencing & deconvolution | Direct, per-well assessment |

| Primary Readout Method | NGS of sgRNA abundance | Various (imaging, biochemical, etc.) |

| Typical Scale | Genome-wide (thousands of genes) | Focused libraries or genome-wide |

| Phenotypic Scope | Binary outcomes (viability, FACS) | Simple to complex multiparametric |

Strategic Considerations for Platform Selection

The choice between pooled and arrayed screening formats depends on multiple experimental factors. Assay compatibility is crucial; pooled screens are restricted to binary assays where cells can be physically separated based on the phenotype, while arrayed screens accommodate diverse assay types including high-content imaging and multiparametric analyses [11] [9]. Cell model characteristics also influence selection; pooled screens require proliferating cells that can stably maintain integrated sgRNAs, whereas arrayed screens work with various cell types, including primary and non-dividing cells [11]. Additionally, researchers must consider equipment requirements (arrayed screens often need automated liquid handling and high-content imaging systems), labor investment (pooled screens require extensive bioinformatics analysis), and cost structure (arrayed screens have higher upfront costs but can provide more information-rich datasets) [11] [9].

Table 2: Practical Considerations for Selecting a Screening Platform

| Consideration | Pooled Screening | Arrayed Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Assay Types | Cell viability, FACS-based sorting | High-content imaging, multiparametric, biochemical |

| Ideal Cell Models | Rapidly dividing, easy-to-transduce cells | Primary cells, neurons, iPSCs, complex co-cultures |

| Equipment Needs | Standard cell culture, NGS, computational resources | Automated liquid handlers, high-content imagers |

| Data Analysis Complexity | High (bioinformatics, statistical deconvolution) | Lower (direct well-to-well comparisons) |

| Typical Workflow Timeline | Longer (library prep, expansion, sequencing) | Shorter (direct phenotypic assessment) |

| Cost Structure | Lower upfront, higher sequencing costs | Higher upfront (reagents, equipment), lower per-assay |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Pooled CRISPR Screening

Library Design and Preparation

The foundation of a successful pooled screen lies in careful gRNA library design. For a genome-wide human screen, typically 4-10 sgRNAs are designed per gene to ensure statistical robustness and account for variable editing efficiencies [13] [11]. sgRNAs should target early exons of protein-coding genes to maximize frameshift probability, with careful off-target prediction using bioinformatics tools like CRISPOR or CHOPCHOP to minimize non-specific editing [13]. The library is synthesized as oligonucleotide pools, then cloned into lentiviral vectors containing selectable markers (e.g., antibiotic resistance) [13] [11]. After transformation into E. coli, the plasmid library is amplified and validated by NGS to ensure equal sgRNA representation before lentiviral packaging in 293T cells [11].

Cell Transduction and Selection

The lentiviral library is transduced into Cas9-expressing cells at a low MOI (typically 0.3-0.5) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA [13] [11]. Transduction efficiency is optimized to achieve 30-50% infection rates to minimize multiple infections per cell. Forty-eight hours post-transduction, cells are placed under antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin) for 5-7 days to eliminate non-transduced cells, then expanded to achieve sufficient coverage (typically 500-1000 cells per sgRNA to prevent stochastic drift) [13] [4].

Phenotypic Selection and Analysis

The selected cell population is divided into experimental and reference groups, with the experimental arm subjected to the selective pressure of interest (e.g., drug treatment, nutrient deprivation) while the reference arm remains unperturbed [10] [11]. After a sufficient selection period (typically 2-3 weeks for negative selection screens), genomic DNA is extracted from both populations and sgRNA sequences are amplified with sample barcodes for multiplexed NGS [11]. Sequencing reads are aligned to the reference library, and sgRNA abundances are compared between conditions using specialized algorithms like MAGeCK or BAGEL to identify significantly enriched or depleted sgRNAs [14].

Diagram 1: Pooled screening workflow.

Protocol for Arrayed CRISPR Screening

Library Format and Preparation

Arrayed libraries are formatted as individual sgRNAs in multiwell plates (commonly 96-, 384-, or 1536-well formats) [12]. sgRNAs can be provided as chemically synthesized oligonucleotides (for RNP formation), plasmid DNA, or pre-packaged viral particles [12] [11]. For RNP-based approaches, which offer high editing efficiency and minimal off-target effects, crRNA:tracrRNA complexes are pre-assembled with recombinant Cas9 protein to form RNPs immediately before delivery [12]. Each well receives a single sgRNA targeting one gene, though some designs include multiple sgRNAs per well targeting the same gene to enhance knockout efficiency [12].

Cell Seeding and Transfection

Cells are seeded into multiwell plates at optimized densities for the specific assay duration and readout. For proliferating cells, reverse transfection approaches are often employed, where transfection reagents are pre-dispensed into plates before adding cells [12]. Cas9 can be delivered through multiple methods: using stable Cas9-expressing cell lines, co-transfection with Cas9 plasmid, or most effectively as pre-complexed RNP delivered via electroporation or lipid-based transfection [12]. Transfection conditions must be rigorously optimized for each cell type to maximize editing efficiency while maintaining viability.

Phenotypic Assessment and Analysis

After a suitable incubation period (typically 3-7 days to allow for protein turnover and phenotypic manifestation), plates are subjected to phenotypic analysis without the need for sequencing-based deconvolution [12] [11]. Assays are tailored to the biological question and can include high-content imaging of morphological features, viability measurements, reporter gene expression, or secreted factor analysis [9]. Data analysis involves comparing each well directly to control wells, with normalization to plate controls and statistical assessment of phenotype strength. Hit identification is straightforward as each well corresponds to a single genetic perturbation [11].

Diagram 2: Arrayed screening workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Guides Cas9 to specific genomic loci | Both pooled & arrayed (format differs) |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target sites | Both pooled & arrayed |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Efficient delivery & genomic integration | Primarily pooled screens |

| Lipid-Based Transfection Reagents | Delivers RNP or plasmid DNA to cells | Primarily arrayed screens |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-formed Cas9-sgRNA complexes | Primarily arrayed (higher efficiency, lower off-target) |

| Selection Antibiotics | Enriches for successfully transduced cells | Primarily pooled screens |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Quantifies sgRNA abundance | Primarily pooled screens |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Captures complex phenotypic data | Primarily arrayed screens |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Dispenses nanoliter volumes to multiwell plates | Primarily arrayed screens |

Advanced Applications and Integrated Workflows

The complementary strengths of pooled and arrayed screening platforms make them ideally suited for sequential application in target discovery pipelines. A common strategy employs pooled screening as a primary discovery tool to identify a broad set of candidate genes associated with a phenotype, followed by arrayed screening for secondary validation and detailed characterization of hits in more physiologically relevant models [11] [9]. This integrated approach balances the comprehensive coverage of pooled screens with the rigorous, information-rich validation capability of arrayed screens.

Advanced screening methodologies continue to emerge, addressing limitations of conventional approaches. CRISPR-StAR (Stochastic Activation by Recombination) introduces internal controls by activating sgRNAs in only half the progeny of each cell after clonal expansion, dramatically improving signal-to-noise ratio in complex models like in vivo tumors and organoids [4]. Single-cell CRISPR screening technologies like Perturb-seq and CROP-seq combine pooled CRISPR screening with single-cell RNA sequencing, enabling high-resolution analysis of transcriptional phenotypes resulting from genetic perturbations [14] [10].

Beyond simple knockout screens, CRISPR platforms have diversified to include CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for gene repression and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) for gene activation, both using catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to effector domains [14] [10]. These approaches enable fine-tuning of gene expression and study of essential genes that would be lethal in knockout screens. More recently, base editing and prime editing screens have enabled functional analysis of specific nucleotide variants, expanding CRISPR screening into functional variant characterization [10].

Pooled and arrayed CRISPR screening platforms represent complementary methodologies that together provide powerful tools for functional genomics research and drug discovery. The selection between these platforms depends on multiple factors including the biological question, assay requirements, available resources, and cell model characteristics. Pooled screens offer unparalleled scalability for genome-wide interrogation of binary phenotypes, while arrayed screens enable detailed multiparametric analysis of focused gene sets. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve with improvements in editing precision, delivery methods, and phenotypic readouts, both screening paradigms will remain essential components of the functional genomics toolkit, accelerating the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets across diverse disease areas.

CRISPR screening has revolutionized functional genomics by enabling high-throughput, systematic interrogation of gene function across the entire genome. This powerful approach relies on the coordinated function of three essential components: single-guide RNA (sgRNA) libraries, Cas enzymes, and delivery systems. Together, these elements facilitate the precise perturbation of thousands of genetic targets in parallel, allowing researchers to decipher complex genetic networks, identify key regulators of biological processes, and uncover novel therapeutic targets for disease treatment [15] [9]. The integration of these components has become indispensable for modern drug discovery and development, particularly in oncology, where CRISPR screens have proven invaluable for deciphering key regulators of tumorigenesis, unraveling underlying mechanisms of drug resistance, and optimizing immunotherapy approaches [15].

Table: Core Components of a CRISPR Screening Platform

| Component | Function | Key Considerations | Common Formats/Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Guides Cas enzyme to specific genomic targets; determines screening scope | Specificity, efficiency, off-target risk, coverage | Genome-wide, focused/subset, custom-designed [9] [13] |

| Cas Enzyme | Executes genomic perturbation; determines type of edit | PAM requirement, editing efficiency, size, specificity | Cas9 (knockout), dCas9-KRAB (interference), dCas9-activator (activation) [9] [16] |

| Delivery System | Introduces CRISPR components into target cells | Efficiency, cargo capacity, cell type compatibility, toxicity | Lentiviral, adeno-associated virus (AAV), liposome transfection, electroporation [13] |

sgRNA Libraries: Design and Construction

Library Design Principles

The design of sgRNA libraries is a critical foundational step that directly determines the success and reliability of CRISPR screens. Effective sgRNA design must balance multiple factors to achieve optimal performance. Each sgRNA typically ranges from 18-23 nucleotides in length, with GC content maintained between 40%-60% to ensure stable binding while avoiding complex secondary structures that could impede functionality [13]. Bioinformatic tools are essential for selecting target sequences with maximal on-target efficiency and minimal off-target potential by scanning the entire genome for unique sequences with minimal similarity to non-target regions [13].

Modern library designs incorporate multiple sgRNAs per gene (typically 3-10) to account for variations in efficiency and to provide statistical confidence in screening hits. For instance, in a novel approach called CRISPRgenee, which combines simultaneous gene knockout and epigenetic silencing, researchers used dual-guide RNAs to significantly improve loss-of-function effects and reduce sgRNA performance variance [17]. This approach demonstrates how advanced library design strategies can enhance screening robustness, particularly for challenging targets where conventional single-guide approaches may yield incomplete gene suppression.

Library Types and Applications

sgRNA libraries are broadly categorized based on their scope and application, with each type serving distinct research purposes. Genome-wide libraries encompass sgRNAs targeting nearly all genes in the genome, enabling unbiased discovery of genes involved in biological processes or disease states [15] [13]. These libraries are particularly valuable for identifying novel genetic regulators without pre-existing hypotheses. Focused libraries target specific gene families, signaling pathways, or functional categories, allowing researchers to concentrate resources on genes of particular interest [13]. These are especially useful for validation studies or when investigating specific biological mechanisms.

More specialized libraries have been developed for advanced applications. For example, CRISPRi libraries designed for transcriptional repression typically target promoter regions or transcription start sites (TSS) with truncated sgRNAs (15-20 nt) that maintain binding capability while modulating repression efficiency [17]. Dual-guide libraries represent another advancement, where two sgRNAs are deployed simultaneously against the same target to enhance perturbation efficacy, as demonstrated in the CRISPRgenee system which showed improved depletion efficiency and accelerated gene depletion compared to individual CRISPRi or CRISPRko approaches [17].

Table: Comparison of Common sgRNA Library Types

| Library Type | Scope | Number of Genes Targeted | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide | Entire genome | ~18,000-20,000 protein-coding genes [18] | Novel target discovery, comprehensive functional mapping | Unbiased approach, broad coverage | High cost, complex data analysis, requires large cell numbers |

| Focused/Subset | Specific pathways or gene families | Dozens to hundreds [13] | Validation studies, pathway-specific investigations | Cost-effective, simplified analysis, higher throughput | Limited to pre-defined gene sets |

| Druggable Genome | Commercially targetable genes | ~5,000 genes [18] | Drug discovery, therapeutic target identification | Direct therapeutic relevance | Excludes non-druggable targets |

| CRISPRi/a | Transcriptional regulation | Variable | Gene expression modulation, non-coding regions | Tunable perturbation, avoids DNA damage | Requires specialized Cas variants |

Library Construction Workflow

The construction of sgRNA libraries follows a meticulous process to ensure comprehensive coverage and representation. The workflow begins with oligonucleotide synthesis of designed sgRNA sequences through chemical synthesis or PCR amplification methods [13]. These oligonucleotides are then cloned into appropriate vectors, typically lentiviral backbones that enable efficient delivery and stable integration. The cloning process employs restriction enzymes and DNA ligases to precisely insert the sgRNA sequences into the vectors, creating a recombinant library [13].

A critical quality control step involves transforming the library into bacterial cells (typically E. coli) for amplification, followed by plasmid purification to obtain high-quality library DNA [13]. Throughout this process, maintaining library diversity and representation is paramount, often achieved by using high coverage libraries (>30x) and incorporating negative selection markers like ccdB to enhance cloning accuracy [13]. Finally, the library plasmids are packaged into viral particles using packaging cell lines (e.g., 293T cells) to generate the infectious virus stock ready for delivery into target cells [13].

Cas Enzymes: Mechanisms and Variants

Cas9 and Its Derivatives

The Cas9 nuclease from Streptococcus pyogenes represents the foundational enzyme for most CRISPR screening applications. The native Cas9 functions as a molecular scissors that introduces double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA at sites specified by the sgRNA and adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (NGG for SpCas9) [9] [13]. Following DSB formation, cellular repair mechanisms predominantly through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) often result in insertion/deletion mutations (indels) that disrupt gene function, enabling effective gene knockout [16].

Key advancements have led to the development of catalytically impaired "dead" Cas9 (dCas9), generated through point mutations (D10A and H840A) that abolish nuclease activity while preserving DNA binding capability [16]. dCas9 serves as a programmable DNA-binding platform that can be fused to various effector domains to modulate gene expression without altering DNA sequence. When fused to transcriptional repressor domains like KRAB (Krüppel-associated box), dCas9 becomes a potent tool for CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) that can silence gene expression by up to 1,000-fold [16]. Conversely, fusion to transcriptional activators such as VP64, VP64-p65-Rta (VPR), or synergistic activation mediator (SAM) creates CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems that enhance gene expression [16].

Specialized Cas Variants and Novel Systems

Beyond standard Cas9, numerous specialized Cas variants have been engineered to expand the capabilities of CRISPR screening. Base editors enable precise nucleotide conversions without introducing double-strand breaks by fusing dCas9 or Cas9 nickase with deaminase enzymes. Cytidine base editors facilitate C•G to T•A conversions, while adenine base editors enable A•T to G•C changes [16]. Prime editors represent even more versatile tools that use a reverse transcriptase domain fused to Cas9 nickase to directly write new genetic information into target sites using a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) template [3].

Emerging systems like CRISPRgenee demonstrate innovative approaches that combine multiple functionalities. This system utilizes ZIM3-Cas9 fusions with truncated sgRNAs (15-nt) to simultaneously achieve gene repression and DNA cleavage, resulting in significantly improved loss-of-function effects compared to conventional CRISPRko or CRISPRi alone [17]. The continuous discovery of novel Cas proteins from microbial diversity, including Cas12, Cas13, and miniature Cas variants, further expands the toolkit available for specialized screening applications [3] [13].

Delivery Systems: Methods and Applications

Viral Delivery Methods

Lentiviral vectors represent the most widely used delivery system for pooled CRISPR screens due to their ability to efficiently transduce a broad range of cell types, including non-dividing cells, and achieve stable genomic integration of CRISPR components [9] [13]. The lentiviral delivery process involves packaging sgRNA library plasmids into lentiviral particles using helper plasmids in packaging cell lines (typically 293T cells), followed by transduction of target cells at appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA [18] [13]. A key advantage of lentiviral systems is their capacity for long-term persistence, making them ideal for extended screens requiring continuous gene perturbation.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors offer an alternative viral delivery method with favorable safety profiles and reduced immunogenicity compared to lentiviral systems [13]. While AAV has a smaller packaging capacity that can limit its use for larger constructs, it provides high transduction efficiency for certain cell types and has been particularly valuable for in vivo screening applications. Recent advances in AAV serotype engineering have expanded the tropism and efficiency of AAV-mediated delivery for CRISPR components.

Non-Viral Delivery Methods

Non-viral delivery methods provide important alternatives that avoid limitations associated with viral systems, such as immunogenicity and insertional mutagenesis concerns. Liposome-mediated transfection involves complexing CRISPR reagents with cationic lipids that fuse with cell membranes, releasing the payload into the cytoplasm [13]. This method is particularly suitable for arrayed screens where each sgRNA is delivered separately to multiwell plates. Electroporation uses electrical pulses to create temporary pores in cell membranes through which CRISPR components can enter cells [13]. Modern electroporation systems have achieved high efficiency delivery even in challenging primary cells and stem cells.

The choice between delivery methods depends on multiple factors including cell type, screening format, and experimental requirements. Pooled screens typically utilize viral delivery, while arrayed screens often employ non-viral methods that enable individual treatment of each target across multiwell plates [9]. Recent innovations in nanoparticle-based delivery and exosome-mediated transfer show promise for further expanding the capabilities of CRISPR component delivery, particularly for in vivo applications and hard-to-transfect cell types.

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Pooled CRISPR Screening Protocol

Pooled CRISPR screening represents the most common approach for large-scale functional genomic studies, particularly for identifying genes involved in survival, proliferation, or response to therapeutic agents [9] [18]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for performing a genome-scale pooled CRISPR knockout screen:

Step 1: Library Selection and Preparation Select an appropriate sgRNA library based on experimental goals. For genome-wide screens, libraries typically contain 90,000-100,000 sgRNAs targeting 18,000-20,000 genes [18]. Amplify the library plasmid through large-scale bacterial culture and purify using endotoxin-free maxiprep kits. Determine the plasmid concentration and quality through spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Step 2: Viral Production Package the sgRNA library into lentiviral particles by co-transfecting the library plasmid with packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G) into 293T cells using polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection reagent. Harvest the viral supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection, concentrate using ultracentrifugation or PEG precipitation, and titer using qPCR or functional titration methods [13].

Step 3: Cell Transduction Seed Cas9-expressing target cells at appropriate density (typically 2-5×10^6 cells for coverage of 500× per sgRNA). Transduce cells with the lentiviral library at MOI of ~0.3 to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA. Include polybrene (8 μg/mL) to enhance transduction efficiency. After 24 hours, replace the virus-containing medium with fresh culture medium [18].

Step 4: Selection and Expansion Begin puromycin selection (1-5 μg/mL, concentration determined by kill curve) at 48 hours post-transduction to eliminate non-transduced cells. Maintain selection for 3-7 days until control non-transduced cells are completely eliminated. Expand the transduced cell population while maintaining at least 500× coverage for each sgRNA throughout the experiment [18].

Step 5: Phenotypic Selection and Harvest Apply the selective pressure of interest (e.g., drug treatment, FACS sorting based on markers, or continued culture for essential gene identification). For drug resistance screens, treat cells with IC50-IC90 concentrations of the compound for 2-3 weeks, refreshing drug and media every 3-4 days [18]. Harvest genomic DNA from both the experimental group and the initial plasmid library or day 0 control using maxiprep-scale DNA extraction protocols.

Step 6: Sequencing and Analysis Amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences from genomic DNA using PCR with barcoded primers compatible with high-throughput sequencing. Pool PCR products, purify, and sequence on an Illumina platform to obtain at least 500× coverage per sgRNA. Process sequencing data through alignment tools and quantify sgRNA abundance using specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK) to identify significantly enriched or depleted sgRNAs [18].

Arrayed CRISPR Screening Protocol

Arrayed CRISPR screening provides an alternative format where each sgRNA is delivered separately in multiwell plates, enabling more complex phenotypic readouts including high-content imaging and time-series analysis [9]. This protocol describes the worklow for performing an arrayed CRISPRi screen using dCas9-KRAB:

Step 1: Arrayed Library Formatting Obtain or prepare an arrayed sgRNA library where each well contains a single sgRNA sequence targeting a specific gene. Dilute sgRNAs or lentiviral vectors in individual wells of 96-well or 384-well plates. For CRISPRi applications, design sgRNAs to target transcription start sites (TSS) with 15-20 nt length optimized for efficient repression [17].

Step 2: Cell Seeding and Transduction Seed dCas9-KRAB-expressing target cells into each well of the library plates at optimized density (e.g., 2,000-5,000 cells per well for 96-well format). For viral delivery, add lentiviral particles for each sgRNA at appropriate MOI. For non-viral delivery, transfer sgRNA plasmids using liposome-based transfection reagents optimized for the cell type [9].

Step 3: Phenotypic Assay Implementation After adequate time for gene perturbation (typically 3-7 days depending on protein half-life), perform phenotypic assays. For high-content screens, this may involve fixed-cell immunofluorescence staining, live-cell imaging, or metabolic assays. For time-series analyses, implement automated imaging systems to track phenotypic changes over multiple days [19].

Step 4: Data Acquisition and Analysis Acquire readouts using appropriate instrumentation (high-content imagers, plate readers, or FACS systems). Extract quantitative features from the data (cell count, intensity measurements, morphological parameters) and normalize to control wells. Perform statistical analysis to identify hits showing significant phenotypic changes compared to non-targeting controls, using Z-score or strictly standardized mean difference (SSMD) methods [19].

Advanced Screening Protocol: CRISPRgenee

The CRISPRgenee system represents a novel approach that combines simultaneous gene knockout and epigenetic silencing to enhance loss-of-function efficacy [17]. This protocol outlines its implementation:

Step 1: Vector Construction Clone a dual sgRNA expression construct containing one truncated sgRNA (15-nt) targeting the promoter region for epigenetic repression and one full-length sgRNA (20-nt) targeting a shared exon for DNA cleavage. Incorporate both sgRNAs into a single vector expressing ZIM3-Cas9 fusion protein, which contains active Cas9 nuclease fused to the potent transcriptional repressor domain ZIM3-KRAB [17].

Step 2: Library Delivery and Induction Transduce target cells with the CRISPRgenee library using lentiviral delivery at MOI ensuring single integration. Induce ZIM3-Cas9 expression with doxycycline (0.5-1 μg/mL) for timed activation of both repression and cleavage activities. Include controls with individual components (CRISPRi-only with dCas9-ZIM3 and CRISPRko-only with Cas9) [17].

Step 3: Efficiency Validation and Phenotyping Monitor gene suppression efficiency over time (5-14 days) using antibody staining or qPCR to confirm enhanced loss-of-function compared to individual approaches. Subject cells to phenotypic selection and analyze as in standard pooled screens. The dual-action system typically shows faster gene depletion and reduced sgRNA performance variance, enabling smaller library sizes with 1-3 sgRNAs per gene while maintaining high confidence in hit identification [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Enzymes | SpCas9, dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VPR, Base editors | Executes targeted genomic or transcriptional modifications | Select based on desired perturbation type: complete knockout (Cas9), repression (dCas9-KRAB), or activation (dCas9-VPR) [9] [16] |

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide (e.g., Brunello, GeCKO), Focused, Custom-designed | Guides Cas enzyme to specific genomic targets | Genome-wide libraries provide unbiased discovery; focused libraries enable targeted investigation [9] [13] |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral, AAV, plasmid vectors | Carries CRISPR components into target cells | Lentiviral offers stable integration; AAV has superior safety profile; plasmids for transient expression [13] |

| Cell Lines | Cas9/dCas9-expressing lines, iPSCs, Primary cells | Provides cellular context for screening | Engineered Cas9-expressing lines simplify workflow; iPSCs enable differentiation studies [7] [17] |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin, Blasticidin, Hygromycin | Enriches for successfully transduced cells | Concentration determined by kill curve for each cell line; typically applied 48h post-transduction [18] |

| Assay Reagents | Antibodies, Fluorescent dyes, Viability indicators | Enables phenotypic measurement and cell sorting | Choice depends on readout: FACS requires fluorescent markers; viability screens use proliferation dyes [9] |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | sgRNA amplification, Barcoded adapters | Facilitates sgRNA quantification from genomic DNA | Must maintain complexity during amplification; incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [18] |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Optimization of Screening Parameters

Successful CRISPR screening requires careful optimization of multiple parameters to ensure robust results. Library representation must be maintained throughout the experiment, with recommended coverage of at least 500 cells per sgRNA to account for stochastic effects [18]. Viral titer optimization is critical, as excessively high MOI can lead to multiple sgRNA integrations per cell, complicating data interpretation, while low MOI reduces screening efficiency. Selection conditions should be predetermined through pilot experiments, particularly for drug screens where appropriate concentration (typically IC50-IC90) must balance selection pressure with maintainance of sufficient cell population for analysis [18].

For advanced systems like CRISPRgenee, additional parameters require optimization. The ratio between truncated and full-length sgRNAs must be balanced to achieve both efficient epigenetic repression and DNA cleavage [17]. The timing of Cas9 induction also significantly impacts performance, with earlier induction typically leading to stronger phenotypic effects. Recent studies indicate that continuous induction over 10-14 population doubling times provides optimal depletion of essential genes while minimizing off-target effects [17].

Addressing Common Technical Challenges

Several technical challenges commonly arise in CRISPR screening experiments. Off-target effects remain a concern, particularly for sgRNAs with high similarity to multiple genomic locations. This can be mitigated through careful sgRNA design using bioinformatic tools that predict potential off-target sites, and through the use of recently developed high-fidelity Cas9 variants [13]. Incomplete gene perturbation can lead to false negatives, especially for genes where residual protein expression maintains function. The CRISPRgenee system addresses this challenge by combining multiple perturbation mechanisms to enhance loss-of-function efficacy [17].

Screen-specific artifacts may arise from various sources, including variable sgRNA efficacy, DNA damage toxicity in CRISPRko screens, and cell density effects on selection. Incorporating sufficient biological replicates (typically 3-5), including non-targeting control sgRNAs, and using robust statistical methods that account for multiple testing are essential for distinguishing true hits from background noise [18]. For specialized applications like stem cell screens, additional considerations include minimizing p53-mediated toxicity through CRISPRi rather than CRISPRko approaches, and accounting for variable differentiation efficiencies when interpreting screen results [7].

In the field of functional genomics, CRISPR screening has emerged as a powerful method for elucidating gene function on a large scale. While the foundational technology of CRISPR-Cas9 enables targeted gene knockout (KO), the CRISPR toolkit has expanded to include precise transcriptional modulation through CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa). These approaches allow researchers to move beyond binary gene disruption to fine-tune gene expression levels, enabling more nuanced functional studies that better mimic physiological and pathological states. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate CRISPR approach is critical for designing effective screens that yield biologically relevant insights into gene networks, signaling pathways, and potential therapeutic targets [10] [20].

Core Technologies: Mechanisms and Molecular Components

CRISPR Knockout (KO)

Mechanism: CRISPR-KO utilizes the wild-type Cas9 nuclease, which creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA at sites specified by the guide RNA (gRNA). The cell's primary repair mechanism, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the reading frame, leading to premature stop codons and complete loss of gene function [21].

Considerations: The permanent nature of KO makes it ideal for studying non-essential genes or for positive selection screens. However, the DNA damage response triggered by DSBs can cause cytotoxicity and genomic instability in some cell types. Furthermore, KO is poorly suited for studying essential genes, as their complete disruption is lethal to cells, and for targeting non-coding regions, where small indels may not be sufficient to ablate function [22] [20].

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi)

Mechanism: CRISPRi employs a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) that lacks nuclease activity but retains DNA-binding capability. When fused to a transcriptional repressor domain like the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB), the dCas9-KRAB complex is guided to a promoter region, where it sterically hinders RNA polymerase and recruits chromatin-modifying factors to silence gene transcription. This results in robust, reversible knockdown without altering the DNA sequence [22] [20] [21].

Considerations: CRISPRi is highly specific with minimal off-target effects compared to RNAi. It is particularly valuable for studying essential genes, as it allows for partial knockdowns that are tolerable to cells, and for probing the function of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [22] [20].

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa)

Mechanism: CRISPRa also uses dCas9 but fuses it to strong transcriptional activator domains, such as VP64, p65, or Rta. More advanced systems, like the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM), recruit multiple distinct activators simultaneously to a single promoter. This recruitment significantly enhances the transcription of the target endogenous gene, achieving gain-of-function upregulation from its native genomic context [22] [20].

Considerations: A key advantage of CRISPRa over traditional cDNA overexpression is that it produces more physiologically relevant expression levels and naturally occurring splice variants. This makes it superior for modeling diseases caused by gene haploinsufficiency or for identifying genes that confer resistance to selective pressures, such as drug treatments [22] [20] [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms and key effector molecules for each technology.

Comparative Analysis: A Guide for Selection

The choice between CRISPR-KO, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa depends on the biological question, the nature of the target genes, and the desired phenotypic output. The table below provides a structured comparison to guide this decision.

Table 1: Comparative overview of CRISPR-KO, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa technologies

| Feature | CRISPR Knockout (KO) | CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | Wild-type Cas9 induces DSBs, repaired by NHEJ to create frameshift indels [21]. | dCas9 fused to KRAB repressor blocks transcription [22] [20]. | dCas9 fused to activator domains (e.g., VP64, SAM) recruits transcriptional machinery [22] [20]. |

| Primary Effect | Permanent gene disruption; complete loss-of-function (LOF) [20]. | Reversible gene knockdown; partial/titratable LOF [22] [20]. | Gene upregulation; gain-of-function (GOF) from the endogenous locus [20] [23]. |

| gRNA Targeting Window | Early exons of the coding sequence to disrupt the open reading frame [22]. | -50 to +300 bp from the transcriptional start site (TSS), most effective within +100 bp downstream [22]. | -400 to -50 bp upstream of the TSS [22]. |

| Key Applications | • Identifying non-essential genes• Positive selection screens (e.g., for drug resistance) [10]. | • Studying essential genes• Targeting non-coding RNAs & enhancers• Mimicking drug action [10] [22] [20]. | • Modeling diseases from haploinsufficiency• Identifying genes conferring drug resistance• Overexpressing large or unknown splice variants [10] [20] [23]. |

| Advantages | • Permanent, complete LOF• Well-established and widely adopted | • Reversible & titratable• High specificity vs. RNAi• Minimal off-target effects & no DNA damage• Suitable for non-coding genes [22] [20] [23]. | • Physiological expression levels & splice variants• Superior to cDNA overexpression for large-scale screens [22] [20]. |

| Limitations & Risks | • Cytotoxicity from DSBs• Genomic instability• Unsuitable for essential genes & some non-coding regions [22] [20]. | • Knockdown is incomplete & transient• Efficacy depends on chromatin accessibility [22]. | • Limited by chromatin accessibility• Upregulation may be insufficient for some targets [23]. |

Practical Application: From Theory to Experiment

gRNA Design and Library Selection

The success of a CRISPR screen hinges on effective gRNA design. For CRISPR-KO, gRNAs are typically designed to target early constitutive exons to maximize the probability of a disruptive indel. In contrast, for CRISPRi and CRISPRa, gRNA design is critically dependent on the precise location of the TSS. CRISPRi gRNAs are most effective when targeting a window from -50 to +300 bp relative to the TSS, with peak efficacy just downstream of the TSS. CRISPRa gRNAs perform best in a region -400 to -50 bp upstream of the TSS [22].

For genome-wide screens, pooled lentiviral libraries containing 3-10 gRNAs per gene are standard to ensure statistical robustness and mitigate the risk of individual ineffective gRNAs. Compact, optimized libraries have been developed that maintain high coverage while reducing the number of cells required for screening [22] [15].

Essential Protocols for CRISPR Screening

The following workflow outlines the key steps for performing a pooled CRISPR screen, applicable to KO, i, and a approaches, with notes on critical decision points.

Protocol Steps Explained:

- Select Approach & Library: Choose between KO, i, or a based on your research question (refer to Table 1). Select a corresponding, validated gRNA library (e.g., genome-wide, focused) [10] [15].

- Generate Helper Cell Line: For CRISPRi and CRISPRa, generate a stable cell line expressing the dCas9-effector fusion (e.g., dCas9-KRAB for CRISPRi). This ensures uniform expression and simplifies the screen. For KO, a stable Cas9-expressing line is used [22] [21].

- Deliver gRNA Library: Transduce the helper cell line with the pooled lentiviral gRNA library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single gRNA. Maintain a high representation of cells (e.g., 500-1000 cells per gRNA) to prevent stochastic library dropout [10] [22].

- Apply Selection Pressure: Split the transduced cell population and subject it to the selective condition of interest (e.g., drug treatment, nutrient deprivation, FACS sorting based on a marker). A control population is maintained under standard conditions.

- Analyze gRNA Abundance: Harvest genomic DNA from the selected and control populations. Amplify the integrated gRNA sequences by PCR and subject them to next-generation sequencing (NGS). Computational tools (e.g., MAGeCK) are used to identify gRNAs that are significantly enriched or depleted in the selected population compared to the control [10].

- Validate Hits: Candidate genes identified in the primary screen must be validated. This is typically done by transducing naive cells with individual gRNAs targeting the hit genes and performing secondary assays to confirm the phenotype (e.g., viability assays, western blot, qPCR) [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key reagents and solutions for CRISPR screening

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Effector Plasmid | Expresses the core protein (dCas9-KRAB for CRISPRi; dCas9-activator for CRISPRa) [22] [20]. | Used to create stable "helper" cell lines. The choice of effector (e.g., KRAB vs. SAM) determines the system's potency. |

| Pooled gRNA Library | A collection of thousands of viral vectors, each encoding a specific gRNA, designed to target the entire genome or a specific gene set [15]. | Libraries are available from commercial suppliers. Design (KO/i/a) and scale (genome-wide vs. focused) must align with the screen's goal. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Produces replication-incompetent lentiviral particles to deliver the gRNA library into target cells [22]. | Ensures efficient and stable genomic integration of gRNAs. Low MOI is critical. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Quantifies the relative abundance of each gRNA in the population before and after selection [10]. | The primary readout for a pooled screen. Requires specialized bioinformatic pipelines for analysis. |

| Selection Agents | Applies the selective pressure to uncover gene-phenotype relationships (e.g., cytotoxic drugs, growth factors) [10]. | The nature of the selector defines the screen's purpose (e.g., drug resistance, essentiality). |

Advances and Integrated Applications in Functional Genomics

The field of CRISPR screening is rapidly evolving. A significant advancement is the integration of CRISPR perturbations with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Technologies like Perturb-seq enable researchers to conduct a complex pooled screen and then use scRNA-seq as the readout, capturing the transcriptomic consequences of each individual perturbation at single-cell resolution. This provides unparalleled insight into how gene perturbations alter cellular states, signaling networks, and heterogeneity within a population [10] [21].

Furthermore, base editing and prime editing screens are emerging as powerful tools for functionally annotating single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) at scale, moving beyond simple LOF/GOF to model specific disease-associated mutations [10] [3]. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) is also refining the entire process, from improving gRNA design and predicting off-target effects to interpreting the complex, high-dimensional data generated by these sophisticated screens [3] [21].

CRISPR-KO, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa are complementary technologies that form a comprehensive toolkit for functional genomics. The choice is not about which tool is universally best, but which is most appropriate for the specific biological context. CRISPR-KO remains the gold standard for complete, permanent gene disruption. In contrast, CRISPRi offers a refined, reversible method for knockdown, ideal for probing essential and non-coding genes. CRISPRa unlocks gain-of-function studies by driving endogenous gene expression, providing unique insights into gene dosage effects and resistance mechanisms. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each approach—and by leveraging integrated technologies like single-cell sequencing—researchers can design more insightful screens to accelerate the discovery of novel biological mechanisms and therapeutic targets in drug development.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has evolved from a simple gene-editing tool into a sophisticated platform for precision genome engineering. While early CRISPR applications relied primarily on creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) for gene knockout, this approach has inherent limitations including genotoxicity, unintended large-scale genomic alterations, and restricted application scope [24]. The expanding CRISPR toolbox now includes base editing, prime editing, and epigenetic modulation technologies that overcome these limitations by enabling more precise genetic and epigenetic modifications without requiring DSBs. These advancements are particularly valuable in functional genomics research, where precise perturbation of genetic elements is essential for understanding gene function and regulatory networks.

The natural diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems continues to grow, with current classification encompassing 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes [25]. This expanding repertoire of CRISPR systems provides researchers with a diverse set of molecular tools for different experimental needs. In functional genomics screening, these technologies enable more precise dissection of gene function, from single-nucleotide changes to genome-wide epigenetic remodeling, accelerating both basic biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Base Editing

CRISPR base editing enables direct, irreversible conversion of one DNA base pair to another without requiring double-strand breaks or donor DNA templates. This technology typically utilizes a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease (nickase) fused to a deaminase enzyme that mediates chemical conversion of nucleotide bases [24]. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) catalyze C•G to T•A conversions, while adenine base editors (ABEs) facilitate A•T to G•C transitions. The editing window is precisely defined by the guide RNA, with the nickase activity directing cellular repair mechanisms to incorporate the edited strand.

Recent advancements have produced more sophisticated base editing systems, including dual-strand editing capabilities. Researchers have developed compact Cas12f-based cytosine base editors that unexpectedly gained the ability to edit both target and non-target DNA strands [26]. Through focused mutagenesis and optimization, the team created strand-selectable miniature base editors, including TSminiCBE, which preferentially targets the target strand and has demonstrated successful in vivo base editing in mice. This compact size makes these editors compatible with therapeutic viral delivery vectors, expanding their potential applications in both basic research and clinical translation.

Prime Editing

Prime editing represents a more versatile precise genome-editing technology that can implement all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring double-strand breaks. The system utilizes a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme and employs a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit. This technology significantly expands the scope of editable sequences beyond what is possible with base editors, particularly for transversion mutations and larger sequence modifications.

Prime editing has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in therapeutic contexts. In a recent study focusing on junctional epidermolysis bullosa, researchers developed a prime editing strategy to correct pathogenic COL17A1 variants, achieving up to 60% editing efficiency in patient keratinocytes and successfully restoring the functional type XVII collagen protein [26]. In xenograft experiments, gene-corrected cells demonstrated a remarkable selective advantage, expanding from 55.9% of the input cells to populate 92.2% of the skin's basal layer after six weeks, suggesting that prime editing could provide an efficient and safe treatment for this and other genetic skin disorders.

Epigenetic Modulation

CRISPR-based epigenetic editing enables reversible modulation of gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This approach typically uses a catalytically dead Cas nuclease (dCas9) fused to epigenetic effector domains that can add or remove DNA methylation and histone modifications. CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems recruit transcriptional activators to gene promoters, while CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) systems recruit repressors to silence gene expression.

The reversibility of epigenetic modifications makes this technology particularly valuable for studying dynamic gene regulation processes. Researchers have developed CRISPR-dCas9-based tools to precisely edit the epigenetic state of the Arc gene in specific memory-encoding neurons, demonstrating that targeted chromatin modifications at a single genomic site can bidirectionally control memory expression [26]. The team showed that they could both enhance and suppress fear memory formation by activating or repressing the Arc promoter, with effects that were evident during initial learning phases and persisted even for fully consolidated memories. Remarkably, these epigenetic modifications were reversible within individual animals using anti-CRISPR proteins, providing the first direct causal evidence that site-specific chromatin changes serve as molecular switches for behavioural memory storage and retrieval.

Recent advances have also produced more compact and efficient epigenetic editors. A single LNP-administered dose of mRNA-encoded epigenetic editors has silenced Pcsk9 in mice, reducing PCSK9 by ~83% and LDL-C by ~51% for six months [26]. The compact editors, including a Cas12i3-based variant, enabled durable, liver-specific gene repression with minimal off-target effects, offering a clinically viable platform for long-term gene modulation via transient mRNA delivery.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced CRISPR Editing Technologies

| Technology | Editing Mechanism | Editing Outcomes | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editing | Chemical conversion of bases using deaminase-fused nickase | C•G to T•A (CBE) or A•T to G•C (ABE) | No DSBs; high product purity; efficient in non-dividing cells | Restricted to specific transition mutations; limited editing window |

| Prime Editing | Reverse transcription of edited sequence from pegRNA | All 12 base substitutions; small insertions/deletions | No DSBs; broad editing scope; fewer off-target effects | Lower efficiency than base editing; complex pegRNA design |

| Epigenetic Modulation | Recruitment of epigenetic modifiers to target loci | Reversible gene activation or silencing | No permanent genomic changes; tunable expression modulation | Transient effects; potential for off-target transcriptional changes |

Application Notes for Functional Genomics Research

Functional Genomics Screening with Base Editors

Base editing platforms have revolutionized functional genomics screening by enabling precise single-nucleotide perturbations at scale. CRISPR-base editor screens are particularly valuable for modeling human disease-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and conducting amino acid-saturating mutagenesis studies to map protein functional domains. The high efficiency and precision of base editing allow for the creation of more physiologically relevant disease models compared to traditional knockout screens.

Recent work has demonstrated the power of base editor screens for identifying novel therapeutic targets. A genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screen identified the XPO7-NPAT pathway as a critical vulnerability in TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukaemia, which is notoriously resistant to all current therapies [26]. The researchers discovered that while XPO7 normally suppresses tumours by regulating p53, in TP53-mutated AML, it drives leukaemia growth by retaining NPAT in the nucleus. Targeting this pathway induced replication catastrophe and compromised genomic integrity specifically in TP53-mutated cells, highlighting how functional genomics can reveal novel therapeutic opportunities for recalcitrant cancers.

Base editing has also shown advantages over conventional CRISPR-Cas9 in therapeutic contexts. In a murine model of sickle cell disease, base editing outperformed CRISPR-Cas9 in reducing red cell sickling, despite similar engraftment rates [26]. Base editing demonstrated higher editing efficiency than CRISPR-Cas9 in competitive transplants, with fewer concerns regarding genotoxicity, supporting base editing and lentiviral approaches as more effective therapeutic strategies for SCD.

High-Resolution Functional Mapping with Prime Editing

Prime editing enables functional genomics researchers to systematically assess the functional consequences of specific nucleotide variants with unprecedented precision. This capability is particularly valuable for saturation prime editing, where researchers can introduce every possible nucleotide substitution at a genomic region of interest to comprehensively map functional elements. The ability to make precise sequence changes without double-strand breaks or donor DNA templates makes prime editing ideal for studying non-coding regulatory elements, creating disease-associated point mutations in cell models, and correcting pathogenic variants.

The versatility of prime editing was demonstrated in a study where researchers developed dramatically improved versions of compact gene-editing enzymes called Cas12f1Super and TnpBSuper, which are small enough to fit inside viral delivery vehicles yet show up to 11-fold better DNA editing efficiency in human cells [26]. These enhanced tools could overcome a significant hurdle in gene therapy by combining the precision needed for treating genetic diseases with the practical size requirements for clinical delivery, highlighting how technological improvements continue to expand the applications of advanced CRISPR tools in functional genomics.

Elucidating Gene Regulation with Epigenetic Editors

CRISPR-based epigenetic editing tools provide functional genomics researchers with unprecedented capability to directly manipulate the epigenetic landscape and observe consequent changes in gene expression and cellular phenotype. These tools are particularly valuable for establishing causal relationships between specific epigenetic marks and transcriptional outcomes, mapping functional regulatory elements, and studying the heritability of epigenetic states across cell divisions. The reversibility of epigenetic modifications enables researchers to study dynamic processes of gene regulation in ways that permanent genetic changes do not permit.

Epigenetic editing has demonstrated remarkable potential for treating complex genetic disorders. Japanese researchers employed CRISPR-based epigenome editing to demethylate the Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting control region in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), successfully reactivating silenced maternal genes and restoring proper methylation patterns throughout PWS-associated regions [26]. The epigenetic corrections were maintained when cells were differentiated into hypothalamic organoids, as shown by single-cell analysis, which demonstrated partial restoration of the disrupted gene expression patterns characteristic of PWS, suggesting potential for treating this and other genomic imprinting disorders.

Table 2: Applications in Functional Genomics Research

| Application Domain | Base Editing | Prime Editing | Epigenetic Modulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Function Studies | Functional consequences of SNPs; domain-specific mutagenesis | Saturation variant testing; precise knockout via start codon mutation | Direct promoter/enhancer manipulation; establishing causality in regulation |

| Disease Modeling | Introduction of disease-associated point mutations | Precise recapitulation of patient-specific variants | Modeling epigenetic contributors to disease |

| Therapeutic Target Identification | Resistance mutation screens; functional variant validation | Comprehensive variant-to-function mapping | Identification of druggable epigenetic regulators |

| High-Throughput Screening | Base editor screens for functional variant discovery | Prime editor screens for precise sequence variants | Epigenetic modifier screens for gene regulation networks |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Base Editing for Functional Genomics Screens

This protocol describes the implementation of a base editing screen to identify genetic determinants of drug resistance, utilizing a cytosine base editor (CBE) and a genome-wide sgRNA library.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cytosine base editor (e.g., BE4max)

- Lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., whole-genome Brunello library with appropriate barcoding)

- Target cell line with high proliferation capacity (e.g., HAP1, K562)

- Polybrene (8 μg/mL)

- Puromycin (concentration to be determined by kill curve)

- Selection drug for resistance screen

Procedure:

Library Amplification and Lentivirus Production:

- Amplify the sgRNA library plasmid following manufacturer's instructions, ensuring >200x coverage to maintain library diversity

- Produce lentivirus by co-transfecting HEK293T cells with the sgRNA library plasmid and packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G)

- Concentrate virus using PEG-it or ultracentrifugation; titer using qPCR for functional titer determination

Cell Transduction and Selection:

- Seed 2×10^7 target cells at 20-30% confluence 24 hours before transduction

- Transduce cells at MOI 0.3-0.4 to ensure most cells receive single integrations, using 8 μg/mL polybrene to enhance transduction efficiency

- 24 hours post-transduction, replace medium with fresh complete medium

- 48 hours post-transduction, begin puromycin selection (1-5 μg/mL, concentration determined by kill curve) for 5-7 days to eliminate non-transduced cells

Base Editor Delivery and Screen Implementation:

- Transduce selected cells with CBE-expressing lentivirus or transfert with CBE plasmid/RNP

- 72 hours post-base editor delivery, split cells into treatment and control groups (in biological triplicate)

- Treat with selection drug at predetermined IC50 concentration for 14-21 days, maintaining >500x library coverage at all times

- Passage cells regularly to maintain logarithmic growth

Sample Collection and Sequencing:

- Harvest 2×10^7 cells (≥1000x coverage) at Day 0 (pre-treatment) and from treatment and control groups at endpoint

- Extract genomic DNA using Maxi Prep kit; amplify integrated sgRNA sequences with barcoded primers

- Purify PCR products and prepare sequencing library for Illumina NextSeq with 75 bp single-end reads

Data Analysis:

- Align sequencing reads to sgRNA library reference using MAGeCK or similar analysis pipeline

- Calculate fold-change and statistical significance for each sgRNA between conditions

- Identify significantly enriched genes (FDR < 0.05) as potential resistance determinants

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low library representation: Ensure >500x coverage at all screening stages