From Bacterial Immunity to Biotech Revolution: The Comprehensive History and Discovery of CRISPR Technology

This article traces the journey of CRISPR technology from its initial discovery as a bacterial immune mechanism to its current status as a revolutionary gene-editing tool.

From Bacterial Immunity to Biotech Revolution: The Comprehensive History and Discovery of CRISPR Technology

Abstract

This article traces the journey of CRISPR technology from its initial discovery as a bacterial immune mechanism to its current status as a revolutionary gene-editing tool. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational science behind CRISPR, details its methodological evolution and diverse therapeutic applications, analyzes key challenges and optimization strategies, and provides a comparative assessment against traditional gene-editing platforms. Synthesizing historical context with the latest 2025 clinical advancements, this review serves as a critical resource for understanding both the technical trajectory and future potential of CRISPR in biomedicine.

The Accidental Discovery: Tracing CRISPR's Origins from Bacterial Defense to Genetic Scissors

The period between 1987 and 2000 marks the nascent stage of one of the most significant biological discoveries of the 21st century: the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system. This era was characterized by the initial observation of mysterious repetitive sequences in prokaryotic genomes, whose biological function remained elusive for over a decade. Within the broader context of CRISPR technology research, this foundational period represents the critical first encounter with a genomic structure that would eventually revolutionize genetic engineering [1] [2]. Researchers during this time meticulously documented these unusual patterns without understanding their profound implications as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, setting the stage for a paradigm shift in molecular biology.

The significance of these early observations lies in their cross-domain conservation. The independent discovery of similar repetitive architectures in both bacteria and archaea suggested a fundamental biological role, driving persistent investigation despite the absence of immediate functional explanations [1] [3]. This chapter delineates the key observations, methodological challenges, and evolving hypotheses that characterized the early CRISPR research landscape, providing the essential groundwork for the transformative applications that would follow.

Key Discoveries and Chronological Development

The elucidation of CRISPR's identity and significance was a gradual process, spanning multiple research groups and continents between 1987 and 2000. The table below summarizes the pivotal milestones during this initial observation period.

Table 1: Key Discoveries in CRISPR Research (1987-2000)

| Year | Key Discovery/Event | Lead Researcher(s) | Organism(s) Studied | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | First accidental discovery of unusual interrupted repeats [1] | Yoshizumi Ishino [1] [3] | Escherichia coli | Initial observation of a CRISPR-like sequence; function unknown. |

| 1993 | Identification of similar repeats in archaea [4] [1] | Francisco Mojica [4] [3] | Haloferax mediterranei | Showed conservation across domains of life; suggested possible role in gene regulation or DNA partitioning. |

| 1993-2000 | Systematic identification across diverse prokaryotes [4] [3] | Multiple groups [4] [3] | Various bacteria and archaea | Recognition of a common family of sequences; given multiple names (SRSRs, SPIDRs, LCTRs). |

| 2000 | Proposal of the acronym CRISPR [4] [3] | Francisco Mojica & Ruud Jansen [4] [3] | N/A (Comparative genomics) | Standardized the nomenclature, unifying the field. |

| 2002 | Identification of cas genes [5] [3] | Ruud Jansen et al. [5] [3] | Multiple prokaryotes | Found conserved genes adjacent to CRISPR loci, hinting at a functional complex. |

The Initial Discovery in E. coli (1987)

The first documented encounter with a CRISPR sequence occurred in 1987 when Yoshizumi Ishino and colleagues at Osaka University were conducting a routine analysis of the iap gene (isozyme conversion of alkaline phosphatase) in Escherichia coli [1]. Their objective was unrelated to immune systems or repeats; they were studying the gene responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in the bacterium's periplasm [1]. During sequencing of a 1.7-kbp DNA fragment spanning the iap gene region, they stumbled upon a puzzling downstream sequence [1] [3].

This enigmatic region contained five highly homologous, 28-base-pair repeats, each separated by non-repeating, variable sequences of 32 base pairs (spacers) [1]. The repeats were arranged in a direct, clustered fashion and displayed palindromic characteristics [1] [3]. The authors noted the uniqueness of this structure in their publication, explicitly stating that "five highly homologous sequences of 29 nucleotides were arranged in tandem as direct repeats with 32 nucleotides as spacing" but could not assign any function to it [1]. The technological limitations of the time, which relied on the Klenow fragment for sequencing reactions, made resolving these palindromic sequences particularly challenging due to secondary structure formation, requiring several months of meticulous work to decipher accurately [1].

Expansion to Archaea and Comparative Genomics (1993-2000)

A critical expansion of the field occurred in 1993 when Francisco Mojica, then a PhD student, identified similar sequences in the genome of the halophilic archaeon Haloferax mediterranei [4] [1]. His initial research focused on how this organism adapts to high-salt environments, and the discovery of these repeats was, like Ishino's, serendipitous [1]. This finding was pivotal because it demonstrated that these unusual sequences were not an anomaly limited to E. coli but were conserved across two fundamental domains of life—Bacteria and Archaea—implying they held a important and evolutionarily significant biological function [1].

Throughout the 1990s, as more microbial genomes were sequenced, similar repeat clusters were identified in an increasing number of organisms [1] [3]. Different research groups used different names for these structures, including Short Regularly Spaced Repeats (SRSRs) by Mojica, Spacers Interspersed Direct Repeats (SPIDRs), and Large Cluster of Tandem Repeats (LCTRs) [1]. This period was characterized by widespread confusion in nomenclature but growing interest in the sequences' potential role. Early functional hypotheses were speculative, ranging from involvement in gene regulation—potentially by facilitating a B-to-Z DNA transition in halophiles—to playing a role in chromosome partitioning during cell division, given the symmetric location of some clusters around the origin of replication in certain Pyrococcus species [1].

The turning point in nomenclature came around 2000-2002. Francisco Mojica, recognizing that all described sequences belonged to a single family, proposed the acronym CRISPR through correspondence with Ruud Jansen, who first used the term in print in 2002 [4] [3]. This standardized naming convention was crucial for unifying the field and enabling efficient literature searches and comparative analyses.

Structural Characterization of the Repeats

The early research period yielded a detailed, albeit purely descriptive, understanding of the CRISPR locus architecture. The defining features, derived from comparative genomic studies, are summarized below.

Table 2: Structural Characteristics of Early CRISPR Loci

| Structural Component | Description | Functional Implication (Theorized 1987-2000) |

|---|---|---|

| Repeats | Short (24-47 bp), direct, often palindromic sequences; highly conserved within a locus [1] [3]. | Suggested formation of secondary RNA structures; possible protein-binding sites. |

| Spacers | Variable sequences of similar length (∼30-40 bp) interspersed between repeats [1] [3]. | Hypothesized to confer specificity, but the source and target were unknown. |

| Leader Sequence | An AT-rich, non-repetitive region of several hundred base pairs located upstream of the repeat-spacer array [1]. | Proposed to serve as a promoter for transcription of the entire locus. |

| Locus Location | Typically found in intergenic regions [1]. | Supported a potential regulatory role rather than encoding proteins. |

The structural analysis confirmed that CRISPR loci were not random repetitions but highly organized genetic elements. The conservation of the repeat sequences within a given locus was striking, while the spacer sequences were unique, suggesting a mechanism for generating diversity [1]. The presence of a common leader sequence was another key hallmark, strongly implying that the entire array was transcribed as a single unit [1]. The palindromic nature of many repeats led to early suggestions that the transcribed RNA could form stable secondary structures, such as stem-loops, which might be critical for function [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The research conducted during this era relied heavily on foundational molecular biology techniques. The following workflow diagram and detailed protocol outline the key methodological approaches used to identify and characterize these mysterious repeats.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for early CRISPR identification

Detailed Protocol: Identification and Initial Characterization of CRISPR Loci

Objective: To isolate, sequence, and perform initial characterization of unknown repetitive genomic sequences from prokaryotes.

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial/Archaeal Strains: Source of genomic DNA (e.g., E. coli K-12, H. mediterranei).

- Cloning Vectors: M13 mp18 and mp19 phage vectors for single-stranded DNA production [1].

- Enzymes: Restriction enzymes, Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA Polymerase I [1].

- Radioisotopes: [α³²P]-dATP for radioactive labeling of sequencing products [1].

- Membranes: Nitrocellulose or nylon membranes for Southern and Northern blotting.

- Oligonucleotides: Designed based on initial repeat sequences for use as hybridization probes.

Methodology:

Genomic DNA Extraction and Cloning: High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was extracted from the prokaryotic strain of interest. The DNA was partially digested with restriction enzymes and size-fractionated. Fragments of interest (e.g., containing a known gene like iap) were cloned into M13 vectors for sequencing [1].

DNA Sequencing via Sanger Method: Template single-stranded DNA was prepared from the M13 clones. The dideoxy chain termination reaction was performed using the Klenow fragment at 37°C, with reaction products labeled by incorporating [α³²P]-dATP. Sequence ladders were visualized by autoradiography [1]. The palindromic nature of the repeats often caused nonspecific termination, complicating sequencing and requiring manual resolution and subcloning of smaller fragments, a process that could take several months [1].

Sequence Analysis and Comparative Genomics: Manual analysis of sequence chromatograms revealed the direct repeat structures. With the growth of public databases in the 1990s, sequences were compared using early bioinformatic tools (e.g., BLAST) to identify homologous repeat clusters in other sequenced prokaryotes [4] [3].

Experimental Confirmation of Conservation (Southern Blot): To verify the presence of similar repeats in related strains without full sequencing, genomic DNA was digested, electrophoresed, and transferred to a membrane (Southern blotting). The membrane was hybridized with a radioactively labeled probe complementary to the conserved repeat sequence, revealing a characteristic banding pattern in positive strains [1].

Transcriptional Analysis (Northern Blot): To investigate if the loci were transcribed, total RNA was extracted, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to a membrane. Hybridization with a repeat-specific probe revealed multiple RNA transcripts, providing the first evidence that CRISPR loci were functional at the RNA level [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The investigation of CRISPR repeats during this period relied on a suite of core molecular biology reagents. The following table catalogs the key solutions and their specific functions in these early studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Early CRISPR Characterization

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in CRISPR Discovery |

|---|---|

| M13 Bacteriophage Vectors (mp18/mp19) | Essential for generating single-stranded DNA templates required for the Sanger sequencing method of the era [1]. |

| Klenow Fragment | The primary enzyme used in dideoxy sequencing reactions before the advent of thermostable polymerases. Its suboptimal processivity at palindromic repeats made sequencing CRISPR loci challenging [1]. |

| [α³²P]-dATP | Radioactive label for visualizing DNA sequencing ladders via autoradiography and for preparing high-sensitivity probes for Southern/Northern blotting [1]. |

| Oligonucleotide Probes | Synthetic DNA sequences complementary to the conserved repeat regions, used as hybridization probes to identify homologous sequences across different species via blotting techniques [1]. |

| Bioinformatic Databases & Tools | Emerging public genome databases and sequence alignment tools (e.g., BLAST) were crucial for comparing newly found repeats and recognizing CRISPR as a widespread, conserved family [4] [3]. |

Evolving Hypotheses and Functional Speculations

Prior to the seminal realization in 2005 that spacers were derived from foreign genetic elements, several hypotheses were proposed to explain the function of CRISPR loci. The following diagram illustrates the logical progression of these early theories.

Diagram 2: Logical flow of early functional hypotheses for CRISPR

The most prominent early hypotheses included:

- Role in DNA Repair: Eugene Koonin's group initially hypothesized, based on genomic context analysis, that Cas proteins specific to thermophilic archaea and bacteria might constitute a novel DNA repair system [6]. This was a logical inference given the nuclease and helicase motifs found in some Cas proteins [5].

- Involvement in Chromosome Partitioning: The symmetric location of some CRISPR arrays around the chromosomal origin of replication in Pyrococcus species led to the theory that they might serve as loading sites for proteins involved in segregating replicated DNA into daughter cells [1]. However, this model did not hold for the many loci found elsewhere in genomes.

- Gene Regulation: The transcription of the CRISPR loci, confirmed by Northern blotting, and their conservation in halophiles led Francisco Mojica to suggest a potential role in regulating gene expression, possibly by modulating DNA topology [1].

None of these hypotheses fully explained all the observed characteristics, particularly the variable spacer sequences. The field remained in a state of intriguing uncertainty until the next phase of research, which would leverage the growing power of genomics to compare spacer sequences with public databases, leading to the groundbreaking immune system hypothesis.

The period from 2000 to 2007 marked a paradigm shift in understanding CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), transitioning from observation of mysterious genetic repeats to experimental validation of their function as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes. This foundational chapter examines the crucial hypothesis—primarily advanced by Francisco Mojica, Alexander Bolotin, and Eugene Koonin, and later validated by Rodolphe Barrangou and Philippe Horvath—that CRISPR-Cas systems provide heritable, sequence-specific immunity against viruses and plasmids. We detail the key bioinformatic predictions and decisive experimental evidence that established this biological function, which subsequently paved the way for the development of CRISPR-Cas9 as a revolutionary genome-editing tool.

The journey to hypothesizing CRISPR as an adaptive immune system began with the identification of an unusual genetic architecture. Initially discovered in 1987 in the E. coli genome, CRISPR loci consisted of short, palindromic repeats separated by unique "spacer" sequences of similar length [6] [3]. For over a decade, the function of these structures remained enigmatic, with proposed roles ranging from DNA repair to chromosome segregation [3].

A critical turning point emerged circa 2000, when Francisco Mojica, analyzing genomes across multiple microbial species, recognized that these sequences constituted a distinct family [4] [7]. He subsequently named them "Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats" (CRISPR) [3]. The subsequent hypothesis that CRISPR constitutes an adaptive immune system represents a quintessential example of scientific discovery, integrating comparative genomics, bioinformatic analysis, and ultimately, rigorous experimental validation.

The Core Hypothesis: CRISPR as an Adaptive Immune System

The adaptive immune system theory posited that CRISPR-Cas systems allow prokaryotes to acquire resistance to invading genetic elements, such as viruses and plasmids, in a sequence-specific and heritable manner. The table below summarizes the key postulates of this hypothesis and the initial evidence supporting them.

Table 1: Core Postulates of the CRISPR Adaptive Immune System Hypothesis and Initial Evidence

| Postulate | Description | Supporting Initial Evidence (2000-2005) |

|---|---|---|

| Spacer Origin | Spacer sequences are derived from foreign genetic elements (phages, plasmids). | Bioinformatic analyses showed spacer sequences matched viral and plasmid DNA [4] [3]. |

| Adaptive Immunity | Integration of new spacers confers resistance to specific pathogens. | Observation that microbes with spacers matching a virus were resistant to infection [6]. |

| Memory & Heritability | The spacer array provides a genetic record of past infections, passed to progeny. | The CRISPR locus is part of the genome, ensuring heritability of resistance [8]. |

| Specificity | Immunity is highly specific to the pathogen whose DNA matches the spacer. | Specificity was inferred from the precise sequence homology between spacers and foreign DNA [3]. |

The conceptual breakthrough came from simultaneously recognizing the origin of the spacer sequences and their potential function. In 2005, three research groups independently reported the key bioinformatic evidence that spacers often exhibited sequence homology to bacteriophage genomes and other mobile genetic elements [4] [3]. This led to the direct proposition that CRISPR is a prokaryotic immune system capable of adaptive, sequence-based recognition of pathogens [3].

Key Theoretical and Experimental Milestones (2000-2007)

The establishment of the CRISPR adaptive immunity theory was driven by a series of interconnected discoveries between 2000 and 2007.

Bioinformatic Predictions and Mechanism Proposals (2000-2005)

2000-2005: Francisco Mojica's Insight: Mojica's group was instrumental in recognizing the foreign origin of spacers. His observation that viruses could not infect bacteria possessing homologous spacer sequences directly suggested an immunological function [7] [6]. He also hypothesized that the RNA transcript of these spacers could guide the immune response, a mechanism analogous to RNA interference in eukaryotes [3].

May 2005: Alexander Bolotin and the Discovery of Cas9: While studying Streptococcus thermophilus, Bolotin and colleagues identified a unique CRISPR locus lacking some known cas genes but containing a novel, large gene encoding a protein with predicted nuclease activity—later named Cas9 [4]. They also noted a crucial pattern: the viral DNA sequences matching the spacers all shared a common adjacent sequence, which they identified as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [4]. This finding was critical for understanding how the system distinguishes between foreign DNA and the bacterial genome's own CRISPR array.

March 2006: Eugene Koonin's Hypothetical Scheme: Using computational analysis, Eugene Koonin and his team formally proposed a hypothetical model for CRISPR-Cas as a bacterial immune system. They abandoned the earlier DNA repair hypothesis and outlined a functional framework based on the inserts derived from phage DNA, providing a theoretical foundation for the field [4].

Experimental Validation and Functional Elucidation (2005-2007)

2005/2007: Rodolphe Barrangou and Philippe Horvath's Definitive Proof: The most compelling experimental evidence came from a Danisco team studying S. thermophilus, a bacterium used in yogurt production. In a landmark 2007 study, they demonstrated that when challenged with a bacteriophage, the bacteria integrated new spacers derived from the phage genome into their CRISPR array [4] [6]. Crucially, they showed that removing these spacers eliminated phage resistance, while adding specific spacers engineered to match a phage sequence conferred resistance to that specific phage [4] [3]. This provided direct, causal evidence for the adaptive immune system hypothesis.

2008: Elucidation of the crRNA and DNA Targeting: Following the 2007 validation, John van der Oost's group identified that the spacer sequences are transcribed into small CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) that guide Cas proteins to the target DNA [4]. Simultaneously, the team of Luciano Marraffini and Erik Sontheimer demonstrated that the target of the CRISPR-Cas system is DNA, not RNA, a finding that was pivotal for its future application in genome editing [4] [3].

The following diagram synthesizes the core mechanism of the adaptive immune function as understood by the end of this pivotal period.

Diagram 1: The CRISPR Adaptive Immune Mechanism. This workflow illustrates the process from initial infection and spacer acquisition to conferred immunity upon re-infection, as validated between 2005 and 2007.

Table 2: Timeline of Critical Discoveries Establishing the Adaptive Immune Function (2000-2007)

| Year | Scientist(s) | Key Contribution | Nature of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Francisco Mojica | Recognized CRISPR as a distinct family across microbes [4]. | Bioinformatic |

| 2005 | Mojica / Others | Reported spacer homology to phage/plasmid DNA [4] [3]. | Bioinformatic |

| 2005 | Alexander Bolotin | Identified Cas9 and the PAM sequence in S. thermophilus [4]. | Genomic Analysis |

| 2006 | Eugene Koonin | Proposed first formal hypothesis of CRISPR as an adaptive immune system [4]. | Computational/Bioinformatic |

| 2007 | Rodolphe Barrangou, Philippe Horvath | Experimentally demonstrated acquired resistance via spacer integration in S. thermophilus [4] [6]. | Experimental Validation |

Experimental Protocols: Validating the Hypothesis

The definitive proof in 2007 came from a series of elegant experiments in Streptococcus thermophilus. The methodology below outlines the core protocol used to test the adaptive immunity hypothesis.

Key Experimental Workflow: Establishing Acquired Resistance

Objective: To determine if exposure to a bacteriophage leads to the acquisition of new spacers in the CRISPR locus and if these new spacers are necessary and sufficient for phage resistance.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains: Streptococcus thermophilus (phage-sensitive starter strain).

- Bacteriophages: Target phages for infection.

- Growth media: Suitable for S. thermophilus culture.

- Molecular biology reagents: PCR primers flanking the CRISPR locus, DNA sequencing reagents, transformation tools for genetic manipulation.

Methodology:

- Phage Challenge: Expose a culture of phage-sensitive S. thermophilus to a high titer of a specific bacteriophage.

- Selection of Survivors: Plate the infected culture to isolate individual bacterial colonies that survive the phage challenge.

- Genetic Analysis:

- PCR and Sequencing: Amplify the CRISPR locus from the genomes of both the original sensitive strain and the surviving resistant colonies using PCR. Sequence the amplified DNA to compare the spacer content.

- Spacer Identification: Analyze the sequences to identify new spacers acquired in the resistant strains. Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., BLAST) to confirm the origin of these new spacers from the genome of the infecting phage.

- Functional Validation:

- Spacer Removal: Genetically remove the newly acquired spacer from the resistant strain. The resulting strain should become phage-sensitive again, demonstrating the spacer's necessity for immunity.

- Spacer Addition: Introduce a spacer sequence derived from a phage into the CRISPR locus of a naive, phage-sensitive strain. This engineered strain should gain resistance to that specific phage, demonstrating the sufficiency of a single spacer for specific immunity [4] [6] [3].

Interpretation: The acquisition of phage-derived spacers in resistant survivors, coupled with the loss of resistance upon spacer deletion and the gain of resistance upon spacer insertion, provides conclusive evidence that the CRISPR system functions as an adaptive immune mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The experiments that validated the CRISPR immune hypothesis relied on a specific set of biological tools and reagents. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Early CRISPR Immunity Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Example in Key Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Model Bacteria | Provided the cellular system for studying CRISPR function in vivo. | Streptococcus thermophilus: Used by Barrangou and Horvath for its well-defined CRISPR loci and industrial relevance [4] [8]. |

| Bacteriophages | Acted as the foreign invaders (pathogens) to challenge the bacterial immune system. | Phages infecting S. thermophilus; their DNA was the source of new spacers [4] [6]. |

| CRISPR Locus Sequencing | Enabled the discovery and comparison of spacer composition before and after phage challenge. | PCR primers flanking the CRISPR array, followed by Sanger sequencing, identified newly acquired spacers [3]. |

| Bioinformatics Databases | Allowed for the identification of spacer origins by homology comparison. | BLAST searches confirmed spacer sequences matched viral or plasmid DNA [4] [3]. |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | Enabled the manipulation of the CRISPR locus to test necessity and sufficiency of spacers. | Tools for precise deletion or insertion of spacer sequences to prove causal relationships [4] [3]. |

The hypothesis that CRISPR is an adaptive immune system, solidified between 2000 and 2007, was not merely an answer to a fundamental biological question. It laid the complete groundwork for a technological revolution. The understanding that CRISPR-Cas systems are programmable, RNA-guided nucleases capable of making precise cuts in DNA molecules directly enabled their repurposing as genome engineering tools. The subsequent work in 2012 to simplify the system into a two-component tool (Cas9 and a single-guide RNA) and its application in eukaryotic cells in 2013 were built directly upon the foundational knowledge of its native biological function [5] [4]. Thus, this period of hypothesis-driven discovery exemplifies how understanding a fundamental microbial defense mechanism can unlock transformative technologies with profound implications for biological research, therapeutic development, and biotechnology.

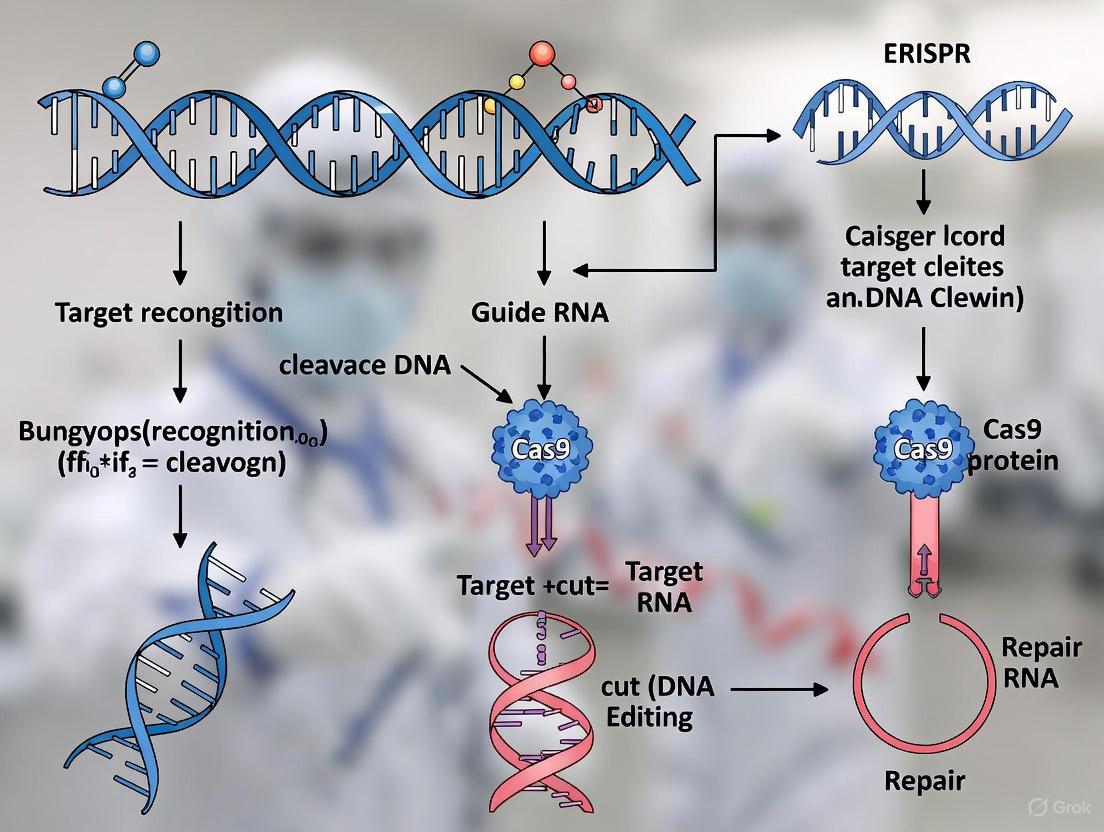

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, derived from an adaptive immune mechanism in prokaryotes, has revolutionized genome engineering due to its precision and programmability [9]. At its core, this system consists of three essential molecular components: the Cas9 endonuclease, which acts as the DNA-cutting machinery; the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which provides the targeting specificity; and the trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a critical scaffold and processing aid [10] [11]. These three elements form a functional complex capable of creating targeted double-strand breaks in DNA, enabling researchers to edit genomes with unprecedented ease [9]. The historical discovery and functional characterization of these components, particularly the relatively late identification of tracrRNA in 2011, were pivotal in transforming a bacterial defense system into a versatile technological platform [4] [11]. This guide examines the structure, function, and interplay of these core components, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical understanding essential for advancing CRISPR-based therapeutics.

Historical Context of Component Discovery

The elucidation of CRISPR-Cas9's key components unfolded through decades of research, with critical discoveries building upon earlier observations to reveal the complete system. Table 1 summarizes the major milestones in identifying the core molecular components.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key CRISPR Component Discoveries

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Initial identification of CRISPR sequences | Yoshizumi Ishino | First observation of unusual repetitive sequences in E. coli [6] |

| 2000 | Term "CRISPR" coined | Francisco Mojica | Recognition that disparate repeat sequences shared common features [4] |

| 2005 | Identification of Cas9 and PAM sequences | Alexander Bolotin | Discovery of Cas9 protein and its PAM requirement for target recognition [4] |

| 2005 | CRISPR as adaptive immunity | Francisco Mojica | Hypothesis that CRISPR is an adaptive immune system based on spacer homology to phage [4] [7] |

| 2007 | Experimental demonstration of adaptive immunity | Philippe Horvath | Confirmed CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses; suggested Cas9 sufficient for interference [4] |

| 2008 | Spacers transcribed into guide RNAs | John van der Oost | Identification that spacer sequences are processed into small crRNAs [4] |

| 2011 | Discovery of tracrRNA | Emmanuelle Charpentier | Identification of tracrRNA as essential component for crRNA maturation in Type II systems [4] [11] |

| 2012 | Biochemical characterization; creation of single-guide RNA (sgRNA) | Virginijus Siksnys; Charpentier & Doudna | Reprogrammed Cas9 with custom guides; fused crRNA and tracrRNA into single guide RNA [4] |

The journey began with the initial discovery of CRISPR sequences in 1987, but their function remained mysterious for years [6]. Francisco Mojica's crucial insight in 2005 that these sequences matched bacteriophage DNA established CRISPR as a prokaryotic immune system [4] [7]. Simultaneously, Alexander Bolotin's discovery of the Cas9 protein and its associated PAM requirement laid groundwork for understanding targeting specificity [4]. The period from 2007-2008 yielded critical understanding of the mechanism, with researchers demonstrating that spacers are transcribed into small RNAs that guide the immune response [4]. The final piece came in 2011 when Emmanuelle Charpentier's team discovered tracrRNA, revealing the complete picture of how the system processes its guides and assembles into a functional complex [11]. This discovery directly enabled the engineering of the dual-RNA complex into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), simplifying the system for widespread applications [4] [11].

Molecular Anatomy of the Core Components

Cas9: The DNA Cutting Machinery

The Cas9 endonuclease serves as the DNA-cutting enzyme within the CRISPR-Cas9 system. This multi-domain protein contains two distinct nuclease domains responsible for cleaving opposite strands of the target DNA: the HNH nuclease domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the crRNA guide sequence, while the RuvC-like nuclease domain cleaves the non-complementary strand [10] [9]. The resulting double-strand break occurs approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), a crucial short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site that Cas9 requires for recognition and binding [10] [4].

Cas9's functional state is a DNA-bound complex where the protein undergoes significant conformational changes upon target recognition. In its apo state (unbound), the protein maintains a relatively open conformation; however, upon binding to both the guide RNA and the complementary DNA target, Cas9 shifts to a closed conformation that positions the nuclease domains for precise cleavage [9]. This structural rearrangement ensures that DNA cutting only occurs when the correct target sequence and PAM are present, providing an important layer of specificity to the system.

Table 2: Cas9 Variants and Their PAM Specificities

| Species/Variant of Cas9 | PAM Sequence | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) | 3' NGG | Most widely used variant; reduced NAG binding in enhanced versions [10] |

| Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9) | 3' NNGRRT or NNGRR(N) | Smaller size beneficial for viral vector packaging [10] |

| xCas9 | 3' NG, GAA, or GAT | Engineered variant with increased PAM flexibility [10] |

| SpCas9-NG | 3' NG | Engineered variant with relaxed PAM requirements [10] |

| Acidaminococcus sp. (AsCpf1/LbCpf1) | 5' TTTV | Cas12 family nuclease; different cleavage mechanism [10] |

crRNA: The Targeting Guide

The CRISPR RNA (crRNA) provides the targeting specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system through its spacer sequence, which is complementary to the desired DNA target [10]. In native bacterial systems, multiple crRNAs are derived from a long precursor transcript (pre-crRNA) containing the entire CRISPR array, which includes direct repeats alternating with spacer sequences [11]. Each mature crRNA consists of a spacer region (approximately 20 nucleotides that define the genomic target) and repeat-derived sequences at both ends that contribute to the structural scaffold for Cas9 binding [10] [11].

The crRNA biogenesis pathway differs significantly between CRISPR system types. In Type I and III systems, the Cas6 nuclease processes pre-crRNA into individual units [9]. However, in Type II systems (including CRISPR-Cas9), crRNA maturation requires tracrRNA and RNase III, as detailed in Section 3.3 [11]. This fundamental difference in processing mechanisms reflects the evolutionary diversity of CRISPR systems, with the Type II pathway being particularly relevant for most genome engineering applications.

tracrRNA: The Scaffold and Processing Aid

The trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) is perhaps the most underappreciated yet essential component of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Discovered in 2011 through small RNA sequencing in Streptococcus pyogenes, tracrRNA exists as multiple transcripts (171-nt and 89-nt primary transcripts processed to a mature 75-nt form) that are encoded adjacent to the cas9 gene [11]. The tracrRNA contains an anti-repeat region that base-pairs extensively with the repeat sequences in the pre-crRNA, forming a duplex that recruits the host endoribonuclease RNase III for processing [4] [11].

This RNA molecule serves two critical functions: first, it acts as a scaffold that links the crRNA to Cas9, facilitating the formation of a stable ribonucleoprotein complex; and second, it is essential for crRNA maturation in native Type II systems [11]. The tracrRNA's anti-repeat domain (approximately 24 nucleotides) base-pairs with the repeat regions of the pre-crRNA, creating a double-stranded RNA substrate that RNase III recognizes and cleaves [11]. After processing, the mature crRNA and tracrRNA remain associated as a dual-RNA complex that guides Cas9 to its DNA targets [11].

The discovery that tracrRNA and crRNA could be fused into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) simplified the system for laboratory applications, but the native dual-RNA structure remains the biological functional unit [4] [11]. Bioinformatics analyses have revealed substantial diversity in tracrRNA structures across Type II systems, with at least 10 main groups identified based on predicted secondary structure features [11].

The Functional Complex: Component Interplay in DNA Targeting

The CRISPR-Cas9 DNA targeting mechanism involves a precisely orchestrated sequence of molecular interactions between the three core components and their DNA target. Figure 1 illustrates this process, from complex assembly through target cleavage.

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Complex Assembly and DNA Targeting Mechanism

Complex Assembly and crRNA Maturation

The process begins with the transcription of the CRISPR array to produce pre-crRNA, which contains multiple repeat-spacer units [11]. Simultaneously, tracrRNA is transcribed from its locus near the cas9 gene. The anti-repeat region of tracrRNA base-pairs with the repeat sequences in pre-crRNA, forming a double-stranded RNA structure that recruits the host RNase III enzyme [11]. In a process facilitated by Cas9, RNase III cleaves the pre-crRNA within the repeat regions, generating individual immature crRNAs that are subsequently trimmed to produce mature crRNAs of approximately 40 nucleotides [11]. The final functional complex consists of Cas9 bound to both the mature crRNA and the processed tracrRNA, forming a ribonucleoprotein ready for DNA target recognition [11].

PAM Recognition and DNA Binding

The Cas9 complex initially scans DNA for appropriate Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequences through three-dimensional diffusion [10] [9]. Upon encountering a valid PAM (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9), the protein undergoes conformational changes that promote DNA melting, enabling the formation of an "R-loop" structure where the target strand displaces to hybridize with the crRNA guide sequence [9]. This PAM recognition mechanism serves as a fundamental safeguard that prevents the CRISPR system from targeting its own CRISPR arrays, which lack PAM sequences [9].

DNA Cleavage Mechanism

Once specific complementarity between the crRNA spacer and target DNA is confirmed, Cas9 activates its nuclease domains to create a double-strand break [10]. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the crRNA guide, while the RuvC domain cleaves the opposite strand [10] [9]. This coordinated cleavage results in a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3-4 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [10]. The cell then repairs this break through either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), enabling various genome editing outcomes including gene knockouts, insertions, or precise modifications [9].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Component Functions

Key Methodologies in CRISPR Research

Researchers have employed diverse experimental approaches to characterize the structure and function of CRISPR components. Biochemical reconstitution has been instrumental in defining the minimal requirements for DNA cleavage, with studies demonstrating that Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA constitute the essential components for targeted DNA interference [4]. Heterologous expression experiments, such as those showing that CRISPR systems function when transferred between bacterial species, confirmed these systems are self-contained units with all necessary components encoded within their loci [4].

Structural biology techniques including X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have provided atomic-level insights into Cas9's architecture and its conformational changes during DNA binding and cleavage [9]. These approaches revealed how Cas9 positions its nuclease domains and how guide RNA binding activates the protein for DNA recognition [9]. Additionally, small RNA sequencing was critical for discovering tracrRNA and elucidating its role in crRNA processing, highlighting the importance of nucleic acid analysis in unraveling CRISPR mechanisms [11].

Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Guide RNA (synthetic) | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci | Can be dual-RNA (crRNA+tracrRNA) or single-guide RNA (sgRNA) format [10] |

| Recombinant Cas9 Nuclease | DNA cleavage enzyme | Purified protein for in vitro studies; codon-optimized versions for eukaryotic expression [10] |

| RNase III | Processes pre-crRNA in Type II systems | Host enzyme required for crRNA maturation in native bacterial systems [11] |

| PAM-containing DNA substrates | Target for Cas9 cleavage | Must contain appropriate PAM sequence adjacent to target site for recognition [10] [9] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery of CRISPR components | Encapsulate ribonucleoprotein complexes for therapeutic applications [12] |

The precise understanding of Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA structure and function has enabled the remarkable transition of CRISPR technology from basic bacterial immunity to transformative therapeutic applications. The discovery that these three components constitute a programmable DNA-targeting system paved the way for groundbreaking therapies now advancing through clinical trials, including Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, and multiple investigational treatments for genetic disorders like hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis and hereditary angioedema [12] [13]. As research continues to refine these core components through engineered Cas9 variants with altered PAM specificities, enhanced precision, and novel functionalities like base editing, the fundamental triad of Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA remains the foundation upon which next-generation genomic medicines are being built [10] [12]. For researchers and drug development professionals, deep knowledge of these key molecular components provides the essential framework for developing safer, more effective CRISPR-based therapeutics.

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a critical short DNA sequence required for the function of CRISPR-Cas systems. This motif, typically 2–6 base pairs in length, is located directly adjacent to the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR complex [14] [15]. The PAM sequence serves as a fundamental "self" versus "non-self" discrimination mechanism, enabling CRISPR systems to precisely identify and cleave foreign invading DNA while avoiding autoimmunity against the bacterial host's own genome [14]. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' (where "N" can be any nucleotide base), located immediately downstream of the target DNA sequence [15] [16]. The discovery and understanding of the PAM have been instrumental in transforming CRISPR from a bacterial immune system into a revolutionary genome engineering tool.

Historical Discovery: The PAM in the Context of CRISPR Research

The history of PAM discovery is inextricably linked to the broader elucidation of the CRISPR-Cas system. The story begins not with PAM itself, but with the initial observation of unusual genetic structures in prokaryotes.

The Early Years: Identifying CRISPR Sequences

In 1987, Japanese researchers first discovered clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) in the Escherichia coli genome, though their function remained mysterious [5] [7]. Throughout the 1990s, Francisco Mojica at the University of Alicante characterized these sequences across multiple microorganisms and, in 2000, recognized that disparate repeat sequences shared common features, coining the term CRISPR [4]. The breakthrough came in 2005 when Mojica reported that these sequences matched snippets from bacteriophage genomes, correctly hypothesizing that CRISPR functions as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes [4] [7].

The PAM Discovery and Its Significance

The PAM sequence was first identified in May 2005 by Alexander Bolotin and colleagues at the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) [4]. While studying the CRISPR locus in Streptococcus thermophilus, they noted that spacers homologous to viral genes all shared a common sequence at one end—the protospacer adjacent motif [4]. This observation was crucial because it revealed a fundamental aspect of the CRISPR targeting mechanism. Bolotin's team also discovered a novel Cas protein with predicted nuclease activity, now known as Cas9, which would become the cornerstone of CRISPR genome editing [5] [4].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in PAM and CRISPR Discovery

| Year | Discoverer(s) | Breakthrough | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Ishino et al. | First discovery of CRISPR sequences in E. coli | Initial observation of unusual genetic structures [5] |

| 2000 | Francisco Mojica | Coined the term CRISPR; recognized common features | Unified previously disparate observations [4] |

| 2005 | Alexander Bolotin | Identified PAM sequence and discovered Cas9 | Revealed key targeting mechanism and main editor enzyme [4] |

| 2005 | Francisco Mojica | CRISPR matches bacteriophage sequences | Established CRISPR as adaptive immune system [4] |

| 2007 | Barrangou & Horvath | Experimental proof of adaptive immunity in S. thermophilus | Confirmed CRISPR function; applied in bacterial vaccination [5] [4] |

The following timeline visualizes the key discoveries in CRISPR research that led to the identification and understanding of the PAM sequence:

The Functional Role and Mechanism of the PAM Sequence

Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination

The fundamental biological function of the PAM is to protect the host bacterium from its own CRISPR system. When the Cas1-Cas2 complex acquires spacers from invading viral DNA, it incorporates them into the bacterial CRISPR array without the adjacent PAM sequence [14] [15]. Consequently, when Cas effector proteins later scan the cell for foreign DNA, they only target sequences that are both complementary to the crRNA and adjacent to the correct PAM. The bacterial genome itself contains the spacers but lacks the flanking PAM, thus preventing autoimmune destruction [15]. This elegant mechanism ensures that the bacterial immune system exclusively attacks foreign genetic elements while preserving host genomic integrity.

The Molecular Mechanism of PAM Recognition

At the molecular level, PAM recognition initiates the process of DNA interrogation by Cas proteins. For Cas9, the PAM is recognized by a PI domain within the protein, which causes local DNA melting and facilitates the formation of an R-loop structure where the target DNA strand is displaced and the complementary strand pairs with the crRNA [14]. The PAM sequence is located directly downstream of the target DNA region (the protospacer), and the Cas9 nuclease creates a double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM [15] [17].

The recognition process follows a specific sequence:

- PAM Binding: Cas proteins first scan DNA for compatible PAM sequences [14]

- DNA Melting: PAM binding induces local unwinding of the DNA duplex [14]

- Seed Sequence Interrogation: The "seed sequence" (8-10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA) begins annealing to the target DNA [17]

- Full Complementarity Check: If seed matching is successful, complete pairing between gRNA and target DNA occurs [17]

- Cleavage Activation: Successful recognition triggers Cas nuclease activity [17]

Table 2: PAM Sequences and Properties of Commonly Used CRISPR-Cas Systems

| CRISPR Nucleases | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | Most widely used; first Cas9 adapted for eukaryotic editing [15] [17] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRR(T) | Smaller size beneficial for viral packaging [15] |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | Longer PAM; higher specificity [15] |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV | Creates staggered cuts; processes its own crRNAs [15] [17] |

| Cas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | Thermostable; used in diagnostic applications [15] |

| xCas9 | Engineered from SpCas9 | NG, GAA, GAT | Broad PAM recognition; increased fidelity [17] |

| SpRY | Engineered from SpCas9 | NRN (prefers NGN) | Near-PAMless variant; greatly expanded targeting range [17] |

Experimental Methods for PAM Identification and Characterization

As CRISPR technologies advanced, robust experimental methods emerged to characterize PAM requirements for both naturally occurring and engineered Cas nucleases. These methods have evolved from computational approaches to sophisticated high-throughput experimental techniques.

Evolution of PAM Determination Methods

Early PAM identification relied on in silico approaches through alignments of protospacers to identify consensus sequences [14]. While fast and accessible, these computational methods couldn't distinguish between functional PAMs for spacer acquisition versus target interference, and were limited by available phage genome sequences [14].

The plasmid depletion assay represented a significant experimental advancement. This negative selection approach involves transforming a host with an active CRISPR-Cas system with a plasmid library containing randomized DNA stretches adjacent to target sequences [14]. Plasmids with "inactive" PAMs that aren't recognized by the Cas nuclease are retained, allowing identification of functional PAMs through sequencing of the remaining plasmids [14].

More recently, PAM-SCANR (PAM screen achieved by NOT-gate repression) enabled high-throughput in vivo PAM screening using a catalytically dead Cas9 variant (dCas9). When dCas9 binds to a functional PAM, it represses GFP expression, allowing sorting by FACS and subsequent identification of functional PAM motifs [14].

Advanced Mammalian Cell-Based PAM Determination

A cutting-edge method published in 2025, PAM-readID, addresses the crucial need for PAM determination in mammalian cells, where cellular environment significantly influences PAM specificity [18]. This method uses double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODN) integration to tag cleaved DNA ends bearing recognized PAMs.

The PAM-readID workflow consists of five key steps [18]:

- Library Construction: Create plasmids bearing target sequences flanked by randomized PAMs

- Transfection: Introduce plasmids expressing Cas nuclease, sgRNA, and dsODN into mammalian cells

- Cleavage & Integration: Allow 72 hours for Cas cleavage and NHEJ repair-mediated dsODN integration

- Amplification: PCR amplify integrated fragments using dsODN-specific and target-plasmid-specific primers

- Analysis: High-throughput sequencing and bioinformatic analysis to define PAM recognition profiles

This method successfully defined PAM profiles for SaCas9, Nme1Cas9, SpCas9, SpG, SpRY, and AsCas12a in mammalian cells, revealing non-canonical PAMs such as 5'-NNAAGT-3' for SaCas9 [18]. The experimental workflow is visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PAM Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAM and CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease Variants | DNA recognition and cleavage | SpCas9 (NGG), SaCas9 (NNGRR[T]), Cas12a (TTTV) [15] [17] |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Targets Cas nuclease to specific genomic loci | 20-nucleotide spacer defines target; scaffold binds Cas [17] |

| PAM Library Plasmids | Determining PAM recognition profiles | Contain randomized nucleotide regions adjacent to fixed target [18] |

| dsODN (double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides) | Tagging cleaved DNA ends in PAM-readID | Integrated at cleavage sites during NHEJ repair [18] |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Reduce off-target editing | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9, evoCas9 [17] |

| PAM-Flexible Enzymes | Expand targetable genomic sites | xCas9 (NG), SpCas9-NG (NG), SpRY (NRN) [17] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | PAM sequence analysis and visualization | CRISPRTarget, CRISPRFinder, PAM Wheel visualization [14] |

PAM Engineering and Clinical Applications

Engineering Cas Proteins with Altered PAM Specificities

The limited targeting range imposed by strict PAM requirements has driven extensive protein engineering efforts to develop Cas variants with altered PAM specificities. These engineered enzymes significantly expand the targetable genome space for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

Key engineering approaches include:

- Directed Evolution: Using phage-assisted continuous evolution to generate Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility [17]

- Structure-Guided Engineering: Modifying PAM-interacting domains based on protein-DNA co-crystal structures [17]

- Domain Swapping: Creating chimeric Cas proteins with novel PAM specificities [19]

Notable successes include xCas9, which recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs; SpCas9-NG with NG PAM recognition; and SpRY, a nearly PAM-less variant that recognizes NRN (prefers NGN) and NYN sequences [17]. These advances have dramatically expanded the targeting range of CRISPR systems, enabling access to previously inaccessible genomic regions.

PAM Considerations in Clinical Applications

The translation of CRISPR technologies into clinical applications heavily depends on PAM availability near disease-relevant mutations. The first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine, Casgevy, for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia, utilizes ex vivo editing where PAM constraints are managed during experimental design [12].

For in vivo therapeutic applications, PAM requirements present additional challenges. Successful clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) and hereditary angioedema (HAE) both target genes expressed in the liver, using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that naturally accumulate in hepatic tissue [12]. These therapies use CRISPR to disrupt disease-causing genes, requiring PAM sequences adjacent to the target sites.

Recent advances in personalized CRISPR therapy highlight both the promise and challenges of PAM-dependent genome editing. In 2025, physicians developed a bespoke in vivo CRISPR treatment for an infant with CPS1 deficiency, delivering the therapy via LNPs in just six months from design to administration [12]. This case demonstrates the critical importance of PAM availability when designing personalized therapies for rare genetic mutations.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is accelerating PAM and CRISPR research. AI models are being used to predict protein structures, optimize guide RNA designs, and engineer novel Cas proteins with desired PAM specificities [19]. These computational approaches complement experimental methods, enabling more rapid development of CRISPR tools with expanded targeting capabilities.

The history of PAM research demonstrates how understanding a fundamental biological mechanism—bacterial adaptive immunity—has enabled revolutionary technologies. From its initial discovery in 2005 by Bolotin to the current development of PAM-flexible Cas variants, the PAM sequence has remained a central consideration in CRISPR-based genome editing. As clinical applications expand, ongoing research continues to address the limitations imposed by PAM requirements through both protein engineering and improved delivery methods.

The future of CRISPR-based therapeutics will likely involve a combination of approaches: engineered Cas variants with relaxed PAM specificities for increased targeting range, improved delivery systems to reach target tissues, and advanced screening methods to identify optimal target sites within disease-associated genes. The PAM sequence, once a curiosity of bacterial immunity, now stands as a cornerstone of genome engineering with profound implications for medicine, biotechnology, and basic research.

The 2012 publication by Jinek et al., "A Programmable Dual-RNA–Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity," represents a pivotal moment in the history of CRISPR technology. While the CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) system was first discovered in 1987 [5] and its function as a prokaryotic immune system was elucidated in 2007 [8], the 2012 paper demonstrated for the first time that the CRISPR-Cas9 system could be engineered as a universal programmable tool for cutting DNA at precise locations in vitro [20] [8]. This work laid the essential foundation for all subsequent applications of CRISPR-Cas9 as a genome-editing technology, transforming biological research and therapeutic development.

The journey to this landmark discovery began with foundational research from multiple groups. Francisco Mojica was instrumental in recognizing CRISPR as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes [5]. Later, the roles of the key molecular components were uncovered: the Cas9 nuclease was identified [5], the crRNA (CRISPR RNA) was shown to guide the system to foreign DNA [5], and finally, a second RNA, the tracrRNA (trans-activating CRISPR RNA), was discovered as being essential for processing crRNA and for Cas9 nuclease activity [5]. The critical insight of the 2012 study was the simplification of this natural, multi-component system into a single, programmable endonuclease.

Core Experimental Breakthrough

Research Objective and Hypothesis

The primary goal of the 2012 study was to reconstitute the Type II CRISPR system in vitro to determine whether the Cas9 protein could be programmed with engineered RNA components to cleave specific, pre-determined DNA sequences. The central hypothesis was that the Cas9 enzyme's DNA cleavage activity was RNA-programmable. The researchers proposed that by combining the naturally occurring crRNA and tracrRNA into a single chimeric "guide RNA" (gRNA), they could create a simplified, two-component system (Cas9 + gRNA) capable of inducing double-strand breaks in DNA targets matching the gRNA sequence [8].

Key Experimental System and Methodology

The experiments utilized a purified, recombinant Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 protein and synthetic RNA components. The DNA targets were typically short, linear, double-stranded DNA fragments containing a target sequence adjacent to the requisite Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which for SpCas9 is 5'-NGG-3' [5] [8].

A key methodological innovation was the design of a single-chimeric guide RNA (sgRNA). This was created by fusing the 3' end of the crRNA (which contains the target-complementary "spacer" sequence) to the 5' end of a truncated tracrRNA via a synthetic loop sequence. This chimeric RNA molecule retained the essential functions of both natural RNAs, thereby simplifying the system [8].

The standard DNA Cleavage Assay protocol involved:

- Complex Formation: Incubating the Cas9 protein with the sgRNA (or with separate crRNA and tracrRNA) in a suitable reaction buffer to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

- Reaction Initiation: Adding the target DNA substrate to the pre-formed RNP complex.

- Cleavage Reaction: Conducting the reaction at 37°C in a buffer containing Mg2+ as an essential cofactor [20].

- Reaction Termination and Analysis: Stopping the reaction and analyzing the products using agarose gel electrophoresis to visualize and quantify the cleavage efficiency based on the appearance of shorter DNA fragments.

The following diagram illustrates this streamlined experimental workflow.

The in vitro cleavage assays provided robust quantitative data demonstrating the system's programmability and specificity. The table below summarizes the core findings.

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Findings from the 2012 Study

| Experimental Parameter | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Cleavage Efficiency | High-efficiency, site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) were achieved. | Confirmed Cas9 functions as an RNA-programmable endonuclease. |

| Dual-RNA Requirement | Both crRNA and tracrRNA were necessary for efficient DNA cleavage in the natural system. | Elucidated the fundamental mechanism of the native bacterial immune system. |

| Chimeric gRNA Function | The single-guide RNA (sgRNA) was functionally equivalent to the natural dual-RNA complex. | Simplified the system from three components to two, enabling facile engineering. |

| PAM Specificity | Cleavage was strictly dependent on the presence of a 5'-NGG PAM sequence adjacent to the target site. | Defined a critical targeting constraint and revealed a key mechanism for self/non-self discrimination. |

| Mg2+ Dependence | Cleavage activity was absolutely dependent on the presence of Mg2+ ions. | Identified an essential catalytic cofactor for the Cas9 nuclease. |

A critical finding was the architecture of the Cas9 nuclease, which contains two distinct catalytic domains that cleave opposite DNA strands. The study demonstrated that these domains could be inactivated individually to create a "nickase" (creating single-strand breaks) or together to create a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9). The following diagram details this cleavage mechanism and its engineering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The in vitro demonstration relied on a specific set of core reagents. The table below details these essential materials and their functions, which formed the basis for subsequent CRISPR tool development.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Purified Cas9 Nuclease | The effector enzyme that executes the DNA cleavage; its programmable specificity is the core of the technology. |

| crRNA (CRISPR RNA) | The guide RNA component that contains the ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target DNA. |

| tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA) | Essential RNA component that base-pairs with the crRNA, facilitates processing, and is required for Cas9 nuclease activity. |

| Single-Guide RNA (sgRNA) | A chimeric, synthetic RNA molecule combining the essential parts of crRNA and tracrRNA, simplifying the system. |

| Target DNA Plasmid/Fragment | The double-stranded DNA substrate containing the target sequence and the requisite PAM site for cleavage. |

| Reaction Buffer with MgCl₂ | Provides the optimal ionic and pH conditions for Cas9 activity; Mg2+ is an essential catalytic cofactor. |

Impact and Evolution in Research and Drug Development

The immediate impact of this in vitro demonstration was profound. Within a year, multiple groups had adapted the CRISPR-Cas9 system for genome editing in mammalian cell culture [8], heralding a new era in genetic engineering. For researchers and drug development professionals, this provided a tool of unprecedented simplicity and programmability for gene knockout, knock-in, and modulation [21] [8].

The technology has since evolved dramatically, leading to:

- Advanced Editors: Development of base editors and prime editors for precise single-nucleotide changes without creating double-strand breaks [22].

- Diagnostic Tools: Creation of CRISPR-based diagnostic tests, including for viruses like SARS-CoV-2 [5] [12].

- Therapeutic Breakthroughs: The 2023 approval of Casgevy, the first CRISPR-based medicine for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, marks the clinical culmination of this research [12]. Current clinical trials are exploring in vivo CRISPR therapies for diseases like hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) and hereditary angioedema (HAE) [12] [22].

- Functional Genomics: The development of CRISPR screening platforms, including hypothesis-driven custom libraries, for drug target discovery and dissecting the genetic basis of disease [23] [24].

The 2012 publication by Jinek et al. was a landmark proof-of-concept that successfully harnessed a bacterial defense mechanism, transforming it into a versatile, programmable, and efficient molecular tool. It laid the essential groundwork for a technology that continues to revolutionize basic research and is now delivering on its promise to treat human disease.

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna recognized their development of CRISPR-Cas9 as a method for genome editing, a discovery that has fundamentally reshaped the life sciences [25]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, tracing its origins from a prokaryotic immune mechanism to a programmable genetic scissors. We detail the key molecular components, experimental workflows, and mechanistic insights that enabled the repurposing of this bacterial defense system into a versatile genome engineering platform. Furthermore, we present current clinical applications and quantitative data from recent trials, highlighting the transformative impact of this technology on therapeutic development.

The journey to the 2020 Nobel Prize began not with human genetics, but with fundamental microbiological research. The term CRISPR, an acronym for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, was first coined in 2002 by Francisco Mojica, who identified these unusual DNA repeats in archaea and bacteria and correctly hypothesized their function in adaptive immunity [4] [5]. This built upon observations dating back to 1987, when unusual repetitive sequences in the E. coli genome were first documented [5] [26].

The timeline below summarizes the critical discoveries that led to the development of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool:

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key CRISPR Discoveries

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Unusual repetitive sequences in E. coli | Ishino et al. [5] | Initial observation of what would later be known as CRISPR |

| 2002 | Term "CRISPR" coined; Cas genes identified | Mojica, Jansen et al. [4] [5] | Naming and initial characterization of the system |

| 2005 | CRISPR spacers match phage DNA | Mojica et al.; Bolotin et al. [4] [5] | Identification of CRISPR as an adaptive immune system |

| 2007 | Experimental demonstration of adaptive immunity | Barrangou, Horvath et al. [4] | First functional proof that CRISPR provides resistance to viruses |

| 2011 | Discovery of tracrRNA | Charpentier et al. [4] | Identified a key RNA component essential for the Cas9 system |

| 2012 | In vitro reprogramming of CRISPR-Cas9 | Doudna, Charpentier et al. [25] [4] | Creation of a programmable gene-editing tool |

The period from 2005-2008 saw crucial advancements in understanding the system's mechanism. Researchers discovered that CRISPR systems require Cas (CRISPR-associated) genes [5], that the target molecule is DNA rather than RNA [4], and that spacer sequences are transcribed into small guide RNAs (crRNAs) that direct Cas proteins to complementary DNA sequences [4]. The stage was set for reprogramming this bacterial immune system into a universal gene-editing tool.

The Core Technology: Molecular Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9

Key Molecular Components

The CRISPR-Cas9 system's functionality depends on a minimal set of molecular components that work in concert to achieve targeted DNA cleavage:

- Cas9 Nuclease: The effector protein that creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in DNA. It contains two nuclease domains: the HNH domain that cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the guide RNA, and the RuvC-like domain that cleaves the non-complementary strand [4] [27].

- crRNA (CRISPR RNA): A short RNA molecule containing a ~20 nucleotide guide sequence that is complementary to the target DNA site, providing the system's targeting specificity [5].

- tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA): A necessary RNA component that facilitates the maturation of crRNA and forms a complex with Cas9 [4] [28].

- sgRNA (single-guide RNA): A synthetic fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA into a single RNA chimera, simplifying the system for practical applications [4] [27].

- PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif): A short (2-6 base pair) DNA sequence adjacent to the target site that is essential for Cas9 recognition and cleavage. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' [4] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the relationships and functions of these core components in the CRISPR-Cas9 complex:

The Three-Stage Mechanism of Action

The natural CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as an adaptive immune system in three distinct stages:

- Adaptation (Spacer Acquisition): When a bacterium survives a viral infection, it incorporates a short fragment of the viral DNA (∼20-40 bp) as a "spacer" into its CRISPR locus, creating a molecular memory of the infection [26].

- Expression and Maturation: The CRISPR locus is transcribed into a long precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA), which is processed into mature crRNAs with the help of tracrRNA and Cas9 [4] [5].

- Interference: The mature crRNA-tracrRNA complex guides Cas9 to complementary viral DNA sequences. Cas9 scans DNA for PAM sequences, unwinds the DNA adjacent to the PAM, and if the crRNA matches the target DNA, Cas9 introduces a double-strand break, thereby inactivating the pathogen [4] [27].

The key insight by Charpentier and Doudna was that the tracrRNA and crRNA could be combined into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), and that by simply modifying the 20-nucleotide guide sequence of the sgRNA, the Cas9 nuclease could be programmed to target any DNA sequence of choice, provided it is adjacent to a PAM [25] [28].

Experimental Breakthrough: Reprogramming CRISPR-Cas9In Vitro

Key Experimental Workflow

The seminal experiment by Charpentier and Doudna that led to the reprogramming of CRISPR-Cas9 involved a systematic biochemical approach to reconstitute and simplify the system in vitro [4] [28]. The workflow can be summarized as follows:

Detailed Methodology

Objective: To reconstitute the Streptococcus pyogenes Type II CRISPR system in vitro and engineer it into a programmable gene-editing tool.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified Cas9 protein from S. pyogenes

- DNA templates containing target sequences

- In vitro transcription system for RNA synthesis

- Synthetic crRNA and tracrRNA molecules

- Plasmid DNA substrates for cleavage assays

- Gel electrophoresis equipment for analyzing cleavage products

Procedure:

- Component Isolation: The Cas9 gene was cloned and the protein was expressed and purified. Native crRNA and tracrRNA components were identified and characterized [4] [28].

- System Reconstitution: The minimal components (Cas9, crRNA, tracrRNA) were combined in a buffer system with plasmid DNA targets to reconstitute DNA cleavage activity in vitro [4].

- RNA Engineering: The dual-RNA structure (crRNA:tracrRNA duplex) was redesigned into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) by connecting the 3' end of the crRNA to the 5' end of the tracrRNA via a synthetic linker [4] [27].

- Reprogramming Validation: The guide sequence of the sgRNA was modified to target specific DNA sequences of interest. Cleavage activity was confirmed by incubating the programmed Cas9-sgRNA complex with DNA substrates containing the target sequence and the requisite PAM [25] [4].

- Specificity Verification: Target recognition specificity was validated through mismatch experiments, demonstrating that single-base pair mismatches between the sgRNA and target DNA could significantly reduce cleavage efficiency [27].

Key Outcome: The experiment demonstrated that:

- The CRISPR-Cas9 system could be reduced to two components: Cas9 protein and a programmable sgRNA.

- The system could be targeted to any DNA sequence of choice by simply modifying the 20-nucleotide guide sequence within the sgRNA.

- DNA cleavage required both complementarity between the sgRNA and target DNA, and the presence of a correct PAM sequence adjacent to the target site [4] [27].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Applications

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-stranded breaks in target DNA | Wild-type SpCas9: 1368 amino acids; requires NGG PAM. Variants include high-fidelity (HF-Cas9), Cas9 nickase (nCas9), and catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) [27]. |

| Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci | ~100 nt synthetic RNA or expressed from U6 promoter. 20-nt guide sequence must be complementary to target, with G at position 1 for U6 transcription [4] [27]. |

| Repair Templates | Enables precise genome editing via HDR | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs, ~100-200 nt) or double-stranded DNA donors with ~800 bp homology arms [29]. |

| Delivery Vectors | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Plasmids, mRNA, or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. Viral vectors (AAV, lentivirus) or non-viral methods (electroporation, lipid nanoparticles) [12] [27]. |

| Validation Tools | Confirms editing efficiency and specificity | T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor assays for indel detection; Sanger sequencing; next-generation sequencing for off-target analysis [26]. |

Clinical Translation and Current Applications

The reprogramming of CRISPR-Cas9 has led to its rapid adoption in clinical research and therapeutic development. The following table summarizes key clinical areas where CRISPR-based therapies have shown significant progress:

Table 3: Current Status of CRISPR-Cas9 Clinical Applications

| Disease Area | Therapeutic Approach | Clinical Trial Status / Key Results |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Blood Disorders | Ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem cells | Approved: Casgevy (exa-cel) for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia demonstrates sustained response >2 years [12]. |

| Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR) | In vivo knockdown of TTR gene in liver | Phase III: LNP-delivered therapy shows ~90% reduction in TTR protein sustained over 2 years [12]. |

| Hereditary Angioedema (HAE) | In vivo knockdown of kallikrein gene | Phase I/II: 86% reduction in kallikrein; 8 of 11 high-dose participants attack-free [12]. |

| Oncology | PD-1 knockout in T cells for enhanced immunotherapy | Early trials: First clinical trial for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer demonstrated safety and feasibility [26]. |

| Rare Genetic Diseases | Personalized in vivo CRISPR therapy | Proof-of-concept: Infant with CPS1 deficiency safely received 3 LNP doses with symptom improvement [12]. |

Delivery Technologies in Clinical Development

Effective delivery remains a critical challenge for CRISPR therapeutics. Current approaches include:

- Ex Vivo Editing: Cells are removed from the patient, edited in culture, and reintroduced (used in Casgevy for sickle cell disease) [12].

- In Vivo Viral Delivery: Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) deliver CRISPR components but have limited packaging capacity and potential immunogenicity [27].

- In Vivo Non-Viral Delivery: Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as a promising vehicle, particularly for liver-targeted therapies, with potential for redosing [12] [27].

The therapeutic development pathway for CRISPR-based medicines involves careful consideration of both the editing strategy and delivery modality, as illustrated below:

The recognition of CRISPR-Cas9 with the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry marks a pivotal moment in the history of biotechnology. The fundamental work by Charpentier and Doudna to elucidate the molecular mechanism of this bacterial immune system and reprogram it into a versatile genetic scissors has created a paradigm shift across the life sciences. The technology's simplicity, precision, and programmability have democratized gene editing, accelerating basic research and enabling the development of transformative therapies for previously untreatable genetic diseases.

While challenges remain in delivery efficiency, specificity, and ethical considerations, the rapid clinical translation of CRISPR-based therapies demonstrates the profound impact of this discovery. As delivery technologies advance and editing precision improves, CRISPR-Cas9 and its derivatives are poised to revolutionize therapeutic development, offering new hope for patients with genetic disorders, cancers, and other intractable diseases.

From Lab Bench to Clinic: CRISPR's Methodological Evolution and Breakthrough Applications

The CRISPR-Cas9 system represents a revolutionary advance in genome engineering, enabling precise manipulation of DNA sequences across diverse biological systems. At its core, this technology functions as a programmable DNA-targeting platform where a single guide RNA (gRNA) directs the Cas9 nuclease to create site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA. This mechanism has transformed basic biological research and therapeutic development, offering unprecedented control over genetic information [5]. The system's operation mirrors its natural function in prokaryotic immunity, where it protects bacteria and archaea from mobile genetic elements such as viruses by storing fragments of foreign DNA in genomic CRISPR arrays [4] [5]. When these sequences are transcribed and processed, they guide Cas proteins to recognize and cleave matching invading DNA, providing adaptive immunity [5]. The repurposing of this natural system for programmable genome editing has created a powerful toolkit that is reshaping medicine and biotechnology, with ongoing clinical trials demonstrating its potential to treat genetic disorders, infectious diseases, and cancer [12].

Historical Context of CRISPR Discoveries

The development of CRISPR-Cas9 technology stems from foundational discoveries by numerous researchers across three decades. Table 1 summarizes the key historical milestones that led to our current understanding of the CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key CRISPR-Cas9 Discoveries

| Date | Discoverers | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|