From Bacterial Immunity to Clinical Breakthroughs: The Comprehensive Guide to CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, tracing its evolution from a prokaryotic immune mechanism to a revolutionary gene-editing tool.

From Bacterial Immunity to Clinical Breakthroughs: The Comprehensive Guide to CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, tracing its evolution from a prokaryotic immune mechanism to a revolutionary gene-editing tool. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of CRISPR systems, their diverse methodological applications in biomedicine and agriculture, current strategies for optimizing specificity and delivery, and a comparative analysis with other editing platforms. The scope extends to the latest clinical advancements, including recently approved therapies and ongoing trials, offering a validated perspective on the technology's current landscape and future potential in therapeutic development.

The Natural Origin and Fundamental Mechanics of CRISPR Systems

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and their associated (Cas) proteins constitute an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes that confers sequence-specific protection against mobile genetic elements. This mechanism involves three distinct functional stages: adaptation, expression, and interference. The system's ability to acquire immunological memory from past infections and execute precise nucleic acid cleavage has not only revolutionized our understanding of prokaryotic defense but has also been repurposed as a versatile tool for genome editing. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of the CRISPR-Cas system's biology, mechanisms, and its transformative impact on biomedical research and therapeutic development, framing it within its journey from a bacterial immune mechanism to a cornerstone of modern genetic engineering.

The discovery of CRISPR-Cas represents a paradigm shift in molecular biology. Initially observed as peculiar genetic loci in prokaryotes, these systems are now recognized as adaptive immune mechanisms that provide heritable, sequence-specific immunity against viruses and plasmids [1] [2]. The conceptual breakthrough that these sequences function as a biological memory system paved the way for their development into powerful technologies [3]. The subsequent domestication of the Type II CRISPR-Cas9 system into a programmable gene-editing tool has fundamentally transformed biomedical research, drug discovery, and therapeutic development [4] [5]. This report details the core biology of this system, its molecular mechanisms, and its experimental applications, providing a foundation for its use in research and clinical contexts.

Biological Foundations and Molecular Mechanisms

CRISPR-Cas systems are widely distributed, found in approximately 45% of sequenced bacterial genomes and 83% of archaeal genomes [1]. These systems are genetically diverse and have been classified into two major classes, six types, and numerous subtypes based on their genetic content and architectural features [3].

Core Genomic Architecture

The CRISPR locus is characterized by several key components, as illustrated in Figure 1:

- Direct Repeats: Short, partially palindromic DNA sequences (typically 28-37 base pairs) that are repeated at regular intervals and form the structural backbone of the locus [1].

- Spacers: Variable sequences (32-38 base pairs) interspersed between repeats. These sequences are derived from past invasions of mobile genetic elements, such as bacteriophages or plasmids, and serve as the immunological memory of the system [1] [3].

- Leader Sequence: An AT-rich region upstream of the CRISPR array that often contains a promoter and serves as the site for the integration of new spacers during adaptation [3].

- cas Genes: Genes encoding CRISPR-associated proteins, which are responsible for the various biochemical activities of the immune response, including the acquisition of new spacers and the cleavage of target nucleic acids [1].

The Three Stages of CRISPR-Cas Immunity

CRISPR-mediated immunity proceeds through three functionally distinct stages: adaptation, expression, and interference [1].

Stage 1: Adaptation

The adaptation or "spacer acquisition" phase involves the integration of novel spacers derived from invading nucleic acids into the CRISPR array. This process is mediated by the conserved Cas1-Cas2 protein complex, which captures fragments of foreign DNA (protospacers) and catalyzes their integration into the leader end of the CRISPR array as new spacers, flanked by new repeats [1]. A critical requirement for spacer acquisition in most systems is the presence of a short, conserved sequence adjacent to the protospacer in the invading DNA, known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [1] [3]. The PAM is essential for distinguishing self from non-self, preventing the CRISPR system from targeting the bacterial chromosome.

Stage 2: crRNA Biogenesis

In the expression stage, the CRISPR locus is transcribed as a long precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA). This primary transcript is then processed into short, mature CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs), each containing a single spacer sequence that guides the Cas machinery to complementary foreign nucleic acids [1]. In Type II systems, a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) hybridizes with the repeat regions of the pre-crRNA, facilitating its processing by Cas9 and RNase III into mature crRNAs [3].

Stage 3: Interference

In the final interference stage, the mature crRNA, complexed with Cas proteins, scans the cell for nucleic acids complementary to the spacer sequence. Upon recognition of a matching sequence adjacent to a valid PAM, the Cas nucleases are activated to cleave the target, leading to the degradation of the invading genetic element [1]. The molecular machinery involved in interference varies by system type, as detailed in Table 1.

System Classification and Functional Diversity

CRISPR-Cas systems exhibit remarkable diversity, which is reflected in their classification. The two main classes are defined by the architecture of their interference modules:

- Class 1 (Types I, III, IV) utilize multi-subunit effector complexes for nucleic acid targeting [3].

- Class 2 (Types II, V, VI) employ a single, large Cas protein (such as Cas9, Cas12, or Cas13) for the same function [3].

Table 1: Major Types of CRISPR-Cas Systems and Their Key Characteristics

| Type | Class | Signature Gene | Effector Complex | Target | PAM Requirement | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Class 1 | cas3 |

Multi-subunit (Cascade) | DNA | Yes (5' of protospacer) | Most common in bacteria [1] |

| Type II | Class 2 | cas9 |

Single protein (Cas9) | DNA | Yes (3' of protospacer) | Source of CRISPR-Cas9 tool; requires tracrRNA [1] [3] |

| Type III | Class 1 | cas10 |

Multi-subunit | DNA/RNA | No | Common in archaea; can target RNA transcripts [1] |

Quantitative Analysis of CRISPR System Efficacy

The application of CRISPR systems, both as a native immune system and as a biotechnology tool, can be quantified through various metrics. Recent comparative studies have evaluated the efficacy of different Cas nucleases for specific applications, such as the eradication of antibiotic resistance genes.

Eradication Efficiency of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

A 2025 study systematically compared the ability of three CRISPR systems—Cas9, Cas12f1, and Cas3—to eliminate the carbapenem resistance genes KPC-2 and IMP-4 from Escherichia coli [6]. The target sites were designed within specific regions of these genes (542–576 bp for KPC-2 and 213–248 bp for IMP-4), and the elimination efficiency was assessed.

Table 2: Comparative Efficacy of CRISPR Systems Against Carbapenem Resistance Genes

| CRISPR System | Signature Nuclease | PAM Sequence | Eradication Efficiency (KPC-2/IMP-4) | Resensitization to Ampicillin | Blocking of Plasmid Transfer | Relative Copy Number Reduction (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Cas9 | NGG | 100% / 100% | Yes | ~99% | Baseline |

| CRISPR-Cas12f1 | Cas12f1 | TTTN | 100% / 100% | Yes | ~99% | Baseline |

| CRISPR-Cas3 | Cas3 | GAA | 100% / 100% | Yes | ~99% | Highest |

The study found that while all three systems were 100% effective in eradicating the resistance genes and resensitizing the bacteria to antibiotics, quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis revealed that the CRISPR-Cas3 system showed the highest eradication efficiency in terms of reducing the copy number of the drug-resistant plasmid [6]. This highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate CRISPR system based on the specific application and desired outcome.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

The following section outlines detailed methodologies for leveraging CRISPR systems in research, from studying bacterial immunity to combating antibiotic resistance.

Protocol: Eradicating Plasmid-Borne Antibiotic Resistance Genes

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study demonstrating the use of CRISPR systems to resensitize resistant bacteria [6].

Objective: To eliminate carbapenem resistance genes (e.g., KPC-2, IMP-4) from a model bacterium (E. coli) using a plasmid-based CRISPR system.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strains: E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells harboring the resistant plasmid (e.g., pKPC-2 or pIMP-4).

- CRISPR Plasmids: Recombinant plasmids expressing a Cas nuclease (e.g., pCas9, pCas3, pCas12f1) and the corresponding guide RNA(s) targeting the resistance gene.

- Growth Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar plates.

- Antibiotics: As required for selection (e.g., Tetracycline, Chloramphenicol, Gentamicin, Kanamycin), prepared at standard concentrations.

- Equipment: Thermocycler, electrophoresis system, spectrophotometer for OD600 measurement.

Procedure:

Target Design and Cloning:

- Design spacer sequences (sgRNAs) targeting the resistance gene according to the PAM requirements of the chosen Cas nuclease.

- For Cas9: Select a 30-nt sequence directly upstream of an NGG PAM.

- For Cas12f1: Select a 20-nt sequence directly upstream of a TTTN PAM.

- For Cas3: Select a 34-nt sequence on the antisense strand upstream of a GAA PAM.

- Synthesize oligonucleotides corresponding to the spacer sequences with appropriate overhangs for cloning.

- Digest the recipient CRISPR plasmid with the restriction enzyme BsaI.

- Ligate the annealed oligonucleotides into the digested plasmid backbone to generate the final CRISPR plasmid.

- Design spacer sequences (sgRNAs) targeting the resistance gene according to the PAM requirements of the chosen Cas nuclease.

Transformation:

- Prepare competent cells from the E. coli strain carrying the target resistance plasmid.

- Transform the prepared competent cells with the constructed CRISPR plasmid.

- Plate the transformation mixture on LB agar containing the antibiotics that select for both the resistance plasmid and the CRISPR plasmid.

- Incubate plates overnight at 37°C.

Validation and Analysis:

- Colony PCR: Pick individual transformant colonies and perform colony PCR using primers flanking the target site within the resistance gene. Analyze the PCR products by gel electrophoresis to confirm the loss of the resistance gene.

- Drug Sensitivity Test: Inoculate PCR-positive clones into liquid media without antibiotic selection and grow to saturation. Perform a spot assay or measure the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to confirm restored sensitivity to the relevant antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin).

- Conjugation Assay: To assess the blocking of horizontal transfer, perform a conjugation mating assay with a recipient strain. Calculate the conjugation frequency and compare it to a control without the CRISPR system to confirm the ~99% blocking rate.

- qPCR Confirmation: Perform quantitative PCR with primers specific for the resistance gene and a chromosomal control gene to quantify the reduction in plasmid copy number, confirming the eradication efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The application of CRISPR technology, both for studying its native function and for its biotechnological repurposing, relies on a core set of reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Based Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Plasmid | A vector encoding the Cas nuclease (e.g., Cas9, Cas12f, Cas3). Provides the catalytic component for DNA cleavage. | pCas9 (Addgene #42876) for Type II system editing [6]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Vector | A plasmid or DNA fragment encoding the custom guide RNA (sgRNA or crRNA). Provides the targeting specificity. | Custom plasmid with a BsaI cloning site for sgRNA insertion [6]. |

| Target DNA | The plasmid or genomic locus containing the protospacer and PAM sequence to be targeted. | Plasmid pKPC-2 carrying the KPC-2 carbapenemase gene [6]. |

| Competent Cells | Chemically or electrocompetent bacterial cells ready for plasmid transformation. | E. coli DH5α competent cells prepared for transformation [6]. |

| Selection Antibiotics | Antibiotics used in growth media to maintain selective pressure for plasmids with resistance markers. | Tetracycline, Chloramphenicol, Kanamycin for plasmid selection [6]. |

| AI Design Tools (e.g., CRISPR-GPT) | AI-powered platforms that assist in experimental design, gRNA selection, and prediction of off-target effects. | Accelerating guide RNA design and troubleshooting for complex edits [7]. |

The CRISPR-Cas system is a quintessential example of how understanding a fundamental biological mechanism in prokaryotes can catalyze a technological and therapeutic revolution. Its intrinsic function as an adaptive immune system, characterized by its three-stage mechanism and diverse molecular architectures, provides a rich framework for scientific inquiry. The repurposing of this system, particularly the Class 2 Type II CRISPR-Cas9 system, into a programmable gene-editing tool has created a paradigm shift across biology and medicine. It has accelerated drug target discovery, enabled the creation of precise disease models, and paved the way for a new class of gene therapies for genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases [4] [5]. As the field advances with new editors like Cas12f1 and Cas3, and leverages AI to overcome design challenges, the core principles of prokaryotic immunity remain the foundation upon which these innovations are built [6] [7]. Future progress will depend on continued rigorous research to address challenges related to delivery, efficacy, and safety, ensuring this powerful technology reaches its full potential to transform human health.

The transformation of the CRISPR-Cas system from an obscure bacterial immune mechanism into a revolutionary programmable gene-editing tool represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in modern biotechnology. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles underlying this technology, its molecular mechanisms, and its extensive applications in biomedical research and therapeutic development. We provide a comprehensive analysis of the core components, quantitative data on system performance, detailed experimental protocols, and visualization of key workflows to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge necessary to leverage this technology in their own work. The content is framed within the broader thesis of CRISPR's evolution from a bacterial adaptive immune system to a precision tool that is reshaping drug discovery and therapeutic intervention.

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system represents a paradigm shift in genetic engineering capabilities. Originally identified as an adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea, this system protects prokaryotes from viral infection by recognizing and cleaving foreign genetic elements [8]. The groundbreaking realization that this system could be repurposed as a programmable gene-editing tool has revolutionized biomedical research and therapeutic development [4] [5].

The core innovation lies in the system's programmability: a guide RNA directs Cas nucleases to specific DNA sequences, enabling precise genetic modifications [5]. This technology has overcome previous limitations in genetic engineering, providing researchers with an unprecedented ability to modify, correct, or modulate precise regions of genomic DNA across diverse cell types and organisms [4]. For drug development professionals, CRISPR-Cas systems have accelerated target identification and validation, enabled the creation of sophisticated disease models, and opened new therapeutic avenues for genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases [4] [9].

Molecular Mechanisms: From Bacterial Immunity to Programmable Editing

Core Components and Mechanisms

The CRISPR-Cas system functions as a two-component complex consisting of a Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [5]. The gRNA contains a sequence that binds to Cas9 and a customizable ~20-nucleotide spacer that specifies the target DNA site through complementary base pairing [8] [5]. Upon target recognition, Cas nucleases induce double-strand breaks in DNA, which are subsequently repaired by cellular mechanisms [4] [5].

Two primary DNA repair pathways are harnessed for genome editing:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair mechanism that often results in insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site, leading to gene disruption [4] [9].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a template to introduce specific genetic modifications, enabling gene correction or insertion [4].

Table 1: CRISPR-Cas System Components and Functions

| Component | Type/Variant | Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease | Cas9 | RNA-guided DNA endonuclease creating double-strand breaks | Gene knockout, disruption |

| dCas9 (catalytically inactive) | DNA binding without cleavage | CRISPRi, CRISPRa, gene regulation | |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | DNA cleavage with different PAM requirement; exhibits trans-cleavage activity | DNA editing, diagnostics [8] | |

| Cas13 | RNA-guided RNase; exhibits trans-cleavage activity | RNA targeting, diagnostics [8] | |

| Guide RNA | crRNA | Contains target-complementary spacer | Target recognition [8] |

| tracrRNA | Facilitates crRNA processing (Type II systems) | Cas9 recruitment | |

| sgRNA | Single-guide RNA combining crRNA and tracrRNA | Simplified editing [4] | |

| Repair Template | ssODN | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide | Small insertions, corrections |

| dsDNA | Double-stranded DNA vector | Large insertions, gene replacements |

CRISPR System Diversity and Applications

Beyond the canonical Cas9 system, various CRISPR nucleases with distinct properties have been identified and harnessed:

- Cas9: The most widely used nuclease, requiring an NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) and creating blunt-ended double-strand breaks [4].

- Cas12a: Recognizes T-rich PAM sequences, creates staggered DNA cuts, and exhibits trans-cleavage activity that has been exploited for diagnostic applications [8].

- Cas13: Targets RNA rather than DNA and demonstrates trans-cleavage activity that has been leveraged for RNA detection and manipulation [8].

The development of catalytically inactive dCas9 has further expanded CRISPR applications beyond editing. When fused to effector domains, dCas9 can be used for transcriptional activation (CRISPRa), repression (CRISPRi), epigenetic modification, and base editing without creating DNA double-strand breaks [4] [9].

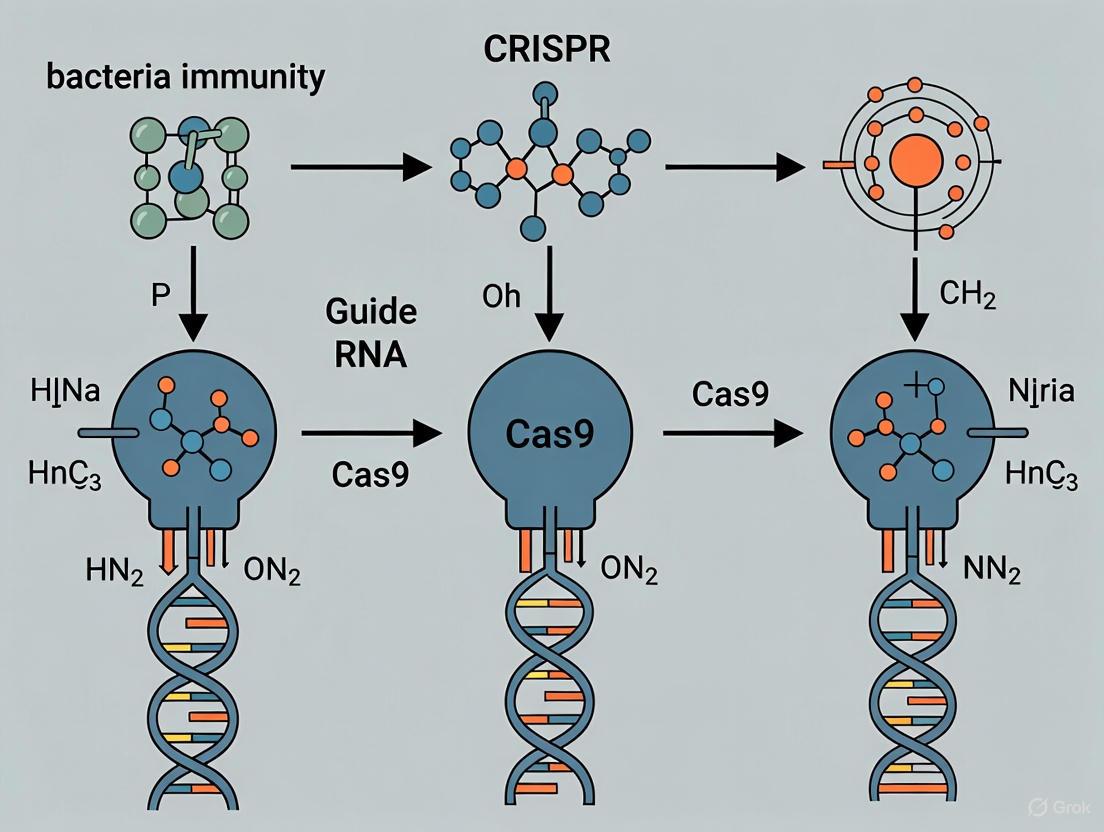

Diagram 1: CRISPR from bacterial immunity to programmable tool. This diagram illustrates the transition of CRISPR-Cas systems from their natural function in bacterial immunity to their repurposing as programmable gene-editing tools with diverse applications.

Quantitative Analysis of CRISPR Systems

Performance Metrics Across Cas Variants

The efficacy of CRISPR systems is quantified through multiple parameters, including editing efficiency, specificity, and sensitivity. Different Cas variants exhibit distinct performance characteristics that make them suitable for various applications.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of CRISPR-Cas Systems

| System | Target | PAM Requirement | Cleavage Type | Efficiency Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | DNA | NGG (SpyCas9) | Blunt ends | 30-80% (varies by cell type) | Gene knockout, large deletions [4] |

| Cas12a | DNA | T-rich (TTTV) | Staggered ends | 20-60% | DNA editing, diagnostics (DETECTR) [8] |

| Cas13 | RNA | Protospacer Flanking Site | RNA cleavage | aM level sensitivity | RNA detection (SHERLOCK), RNA editing [8] |

| dCas9 | DNA | NGG | No cleavage | N/A | Gene regulation, epigen editing [4] [9] |

| Base Editors | DNA | NGG | Chemical conversion | 10-50% | Point mutations without DSBs [4] |

Diagnostic Performance Comparison

CRISPR-based diagnostic platforms have demonstrated exceptional sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional methods, enabling rapid detection of pathogens and genetic variants.

Table 3: Diagnostic Performance Comparison

| Method | Detection Limit | Time to Result | Equipment Needs | Cost per Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-Based | Varies by pathogen | 24-72 hours | Incubators, microscopes | Medium |

| PCR | ~100 copies | 1-4 hours | Thermal cycler, real-time PCR | Medium-High |

| Immunoassay | ng-pg/mL | 1-2 hours | Plate readers, washers | Low-Medium |

| CRISPR-DETECTR | aM levels | 30-60 minutes | Minimal (isothermal) | Low [8] |

| CRISPR-SHERLOCK | aM levels | <60 minutes | Minimal (isothermal) | Low [8] |

Experimental Framework: CRISPR Screening Methodologies

Pooled CRISPR Screening Workflow

Functional genomic screening with CRISPR-Cas9 has become a powerful approach for systematic identification of genes associated with various phenotypes [10] [9]. The pooled screening approach enables genome-wide interrogation of gene function in a highly parallelized manner.

Diagram 2: Pooled CRISPR screening workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in a typical pooled CRISPR screen, from library design to hit validation.

Detailed Screening Protocol

Library Design and Preparation

sgRNA Library Design:

Library Cloning:

- Clone oligo pool into lentiviral backbone using Golden Gate assembly

- Transform into electrocompetent E. coli and plate on large-format bioassay dishes

- Harvest library with maxiprep kit, ensuring >500x coverage of library diversity

Cell Transduction and Selection

Virus Production:

- Transfect HEK293T cells with lentiviral packaging plasmids and library vector

- Harvest virus supernatant at 48h and 72h post-transfection, concentrate if necessary

Cell Transduction:

- Transduce Cas9-expressing target cells at low MOI (MOI=0.3-0.5) to ensure single integration

- Include non-transduced control for selection optimization

- Spinfect at 1000g for 2h at 32°C to enhance transduction efficiency

Selection and Expansion:

- Apply appropriate selection (e.g., puromycin 1-5μg/mL) 24h post-transduction

- Maintain selection for 5-7 days until control cells are completely dead

- Expand cells to maintain >500x library coverage at each passage

Phenotypic Screening and Analysis

Phenotypic Application:

- For negative selection screens: Passage cells for 14-21 days to allow dropout of essential genes

- For positive selection screens: Apply selective pressure (e.g., drug treatment) and collect surviving cells

- Collect timepoints at Day 0 (post-selection), Day 7, Day 14, and Day 21 for longitudinal analysis

Sequencing Library Preparation:

- Extract genomic DNA using maxiprep kits with RNase A treatment

- Amplify sgRNA region with 18 PCR cycles using barcoded primers for multiplexing

- Purify PCR products with SPRI beads and quantify by qPCR before sequencing

Data Analysis with MAGeCK-VISPR:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of CRISPR technologies requires a comprehensive set of specialized reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential components for CRISPR-based research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | S. pyogenes Cas9, AsCas12a, LwaCas13a | Target recognition and cleavage | PAM requirements, specificity, delivery format (RNP, mRNA) |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lentiviral particles, AAV, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Intracellular delivery of editing components | Tropism, payload size, immunogenicity, transduction efficiency [11] |

| Guide RNA Formats | sgRNA expression vectors, synthetic crRNA:tracrRNA | Target specification | Chemical modifications for stability, expression promoter (U6, H1) |

| Detection Tools | CRISPR-detector, T7E1 assay, NGS panels | Editing efficiency and specificity validation | Sensitivity, throughput, cost [12] |

| Cell Culture Models | iPSCs, Primary cells, Organoids | Physiological context for editing | Editability, expansion capacity, relevance to disease |

| Screening Libraries | Genome-wide knockout, CRISPRa/i, focused sublibraries | Functional genomics | Coverage, validation status, application-specific design [9] |

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

The transition of CRISPR technology from basic research to clinical applications has accelerated rapidly, with multiple therapeutic programs now in clinical trials and approved treatments emerging.

Clinical Trial Advancements

Recent clinical developments demonstrate the therapeutic potential of CRISPR-based interventions:

- Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel): The first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine for sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT), representing a landmark validation of the technology [11].

- In vivo CRISPR therapies: The first personalized in vivo CRISPR treatment was administered to an infant with CPS1 deficiency, developed and delivered in just six months using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [11].

- Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR): Intellia Therapeutics' phase I trial demonstrated ~90% reduction in disease-related TTR protein levels sustained over two years of follow-up [11].

- Hereditary angioedema (HAE): CRISPR-Cas9 therapy targeting kallikrein resulted in 86% reduction in target protein and significant reduction in inflammatory attacks [11].

Delivery System Advancements

Delivery remains a critical challenge for CRISPR therapeutics, with significant advances in:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Demonstrated success in liver-directed editing with potential for redosing due to reduced immunogenicity compared to viral vectors [11].

- Viral Vectors: AAV vectors optimized for cargo size and tissue specificity.

- Ex vivo Approaches: Cell therapies engineered outside the body and reintroduced, as exemplified by Casgevy for SCD.

The CRISPR therapeutic landscape continues to expand, with applications in genetic diseases, oncology, infectious diseases, and regenerative medicine, positioning CRISPR at the forefront of the next generation of precision medicines [11] [5].

From Bacterial Immunity to Gene-Editing Revolution

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins function as an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea, protecting them from viral infections [13] [14] [15]. This natural system has been repurposed into a revolutionary genome engineering tool that allows researchers to precisely edit any sequence in an organism's genome [16].

The core components of this system are Cas nucleases, guide RNA (gRNA), and the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence [16] [14]. The system's versatility stems from its programmability; by simply changing the ~20-nucleotide targeting sequence within the gRNA, researchers can redirect the Cas nuclease to virtually any genomic location [14]. This guide details the function and characteristics of these core components, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Core Functional Units

Cas Nucleases: The DNA Cutting Machinery

Cas nucleases are enzymes that create double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA. They are the executive effectors of the CRISPR system. The specific Cas protein used determines the system's properties, including its PAM requirement, size, and cutting mechanism [16] [14].

CRISPR-Cas systems are broadly classified into two classes. Class 1 (types I, III, IV, and VII) utilize multi-protein effector complexes, while Class 2 (types II, V, and VI) employ single-protein effectors like Cas9 and Cas12a, which are more commonly adapted for gene-editing applications due to their simplicity [13] [15]. The known diversity of these systems is rapidly expanding, with a current classification encompassing 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes [13].

Guide RNA (gRNA): The Targeting System

The guide RNA is a synthetic RNA molecule composed of two key parts:

- Scaffold Sequence: Necessary for binding the Cas nuclease [14].

- Spacer Sequence: A user-defined ~20-nucleotide sequence that is complementary to the target DNA and specifies where the Cas nuclease will bind and cut [14].

The gRNA directs the Cas nuclease to the target locus through Watson-Crick base pairing. The location of any mismatches between the gRNA and the target DNA matters significantly; mismatches in the seed sequence (the 8-10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence) are more likely to inhibit cleavage than mismatches farther away [14].

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): The Self vs. Non-Self Discriminator

The PAM is a short, specific DNA sequence (usually 2-6 base pairs) that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR system [16] [15]. Its primary role is to allow the CRISPR system to distinguish between foreign DNA (a valid target) and the bacterium's own CRISPR array (which must not be cleaved) [16] [17].

The spacer sequences stored in the bacterial CRISPR locus are derived from viral DNA but do not include the PAM. Therefore, when the Cas nuclease scans the cell for matching sequences, it will only cleave DNA that has both a complementary protospacer and the correct PAM sequence immediately downstream, thus avoiding autoimmunity [16] [15]. In genome engineering, the presence and location of the PAM sequence are absolute requirements for editing to occur and thus dictate where in the genome a Cas nuclease can be targeted [16] [17].

The Mechanism of CRISPR-Based Immunity and Gene Editing

The core function of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in both bacterial immunity and gene editing involves a sequence of molecular events triggered by the formation of the Cas-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complex.

Diagram 1: Core CRISPR-Cas9 DNA targeting and cleavage mechanism. The process begins with complex formation and proceeds through PAM-dependent scanning, R-loop formation, and complementarity checks before culminating in DNA cleavage, enabling both bacterial immunity and gene-editing applications.

Quantitative Landscape of CRISPR Nucleases

The choice of Cas nuclease is a critical experimental decision. Different nucleases have unique PAM requirements, sizes, and cleavage mechanisms, making them suitable for different applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Commonly Used and Emerging CRISPR Nucleases

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Size (aa, ~) | Cleavage Mechanism | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG [16] [14] [17] | ~1,360 | Blunt DSB, RuvC & HNH domains cut target & non-target strands [14] | Knockout, Knock-in, Activation/Repression |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRR(T) [16] | ~1,050 | Blunt DSB | In vivo delivery where size is a constraint |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT [16] | ~1,100 | Blunt DSB | Editing with longer PAM requirement |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV [16] | ~1,300 | Staggered DSB, single RuvC domain cuts both strands [15] | Knock-in, multiplexed editing |

| Cas12f1 | Engineered | TN and/or TNN [16] [6] | ~400-500 | Staggered DSB | In vivo delivery (extremely small size) |

| Cas14 | Uncultivated archaea | T-rich (e.g., TTTA) for dsDNA [16] | ~400-700 | ssDNA/ssRNA cleavage | Diagnostics, ssDNA targeting |

| Cas3 | Various Prokaryotes | No strict PAM requirement [16] [6] | Large, multi-protein | Processive degradation, large deletions [6] | Large genomic deletions, anti-plasmid applications |

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Eradication Efficiency of CRISPR Systems Against Antibiotic Resistance Genes

| CRISPR System | Target Gene | Eradication Efficiency (Colony PCR) | Resensitization to Antibiotic | Relative Efficiency (qPCR, vs. Cas9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | KPC-2 & IMP-4 | 100% [6] | Successful (Ampicillin) [6] | Baseline |

| CRISPR-Cas12f1 | KPC-2 & IMP-4 | 100% [6] | Successful (Ampicillin) [6] | Lower than Cas9 [6] |

| CRISPR-Cas3 | KPC-2 & IMP-4 | 100% [6] | Successful (Ampicillin) [6] | Higher than Cas9 [6] |

Advanced Nuclease Engineering

To overcome limitations like PAM restrictions, large size, and off-target effects, researchers have engineered numerous variants of Cas nucleases.

- High-Fidelity Cas9s: Variants like eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, and HypaCas9 contain mutations that reduce off-target editing by weakening non-specific interactions with the DNA backbone or enhancing proofreading capabilities [14].

- PAM-Flexible Cas9s: Engineered variants such as xCas9 and SpRY recognize non-NGG PAMs (e.g., NG, GAA, GAT, NRN, NYN), vastly expanding the targetable genome space [14].

- Special-Function Cas9s:

- Immunoevading Cas Proteins: Recently engineered versions of Cas9 and Cas12a have specific immunogenic amino acid sequences masked, reducing immune responses in mice—a crucial advancement for human therapies [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Eradicating Antibiotic Resistance Plasmids

The following protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, details the steps to eradicate carbapenem resistance genes (KPC-2 and IMP-4) from E. coli using three different CRISPR systems (Cas9, Cas12f1, Cas3), enabling a direct comparison of their efficacy [6].

Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial Strains: E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells.

- Resistant Model Plasmids: pKPC-2 and pIMP-4 (constructed by cloning KPC-2 or IMP-4 gene fragments into a vector like pSEVA551 with a tetracycline resistance marker) [6].

- CRISPR Plasmids: pCas9 (Addgene #42876), pCas12f1, and pCas3cRh (Addgene #133773), each containing a compatible antibiotic marker (e.g., chloramphenicol or kanamycin resistance) [6].

- Growth Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and LB agar plates.

- Antibiotics: Tetracycline (10 mg/mL), Chloramphenicol (50 mg/mL), Gentamicin (15 mg/mL), Kanamycin (50 mg/mL), Ampicillin.

- Oligonucleotides: Designed spacers for gRNAs targeting regions within the KPC-2 (542–576 bp) and IMP-4 (213–248 bp) genes.

- Restriction Enzyme: BsaI.

- Ligation Kit.

- Competent Cell Preparation Kit (e.g., TransEasy kit from GeneCopoeia).

Methodology

Part 1: CRISPR Plasmid Construction

- Spacer Design:

- Oligo Annealing: Synthesize and anneal oligonucleotide pairs for each spacer, adding the appropriate sticky ends for the respective BsaI-digested backbone [6].

- Digestion and Ligation: Digest the destination CRISPR plasmids (pCas9, pCas12f1, pCas3) with BsaI. Ligate the annealed spacer fragments into the digested backbones using a rapid ligation kit [6].

- Transformation: Transform the ligation products into competent E. coli DH5α cells and plate on selective media to obtain the final recombinant CRISPR plasmids.

Part 2: Eradication Efficiency Assay

- Prepare Model Bacteria: Transform the pKPC-2 or pIMP-4 plasmid into E. coli DH5α to generate the model drug-resistant bacteria. Select on tetracycline plates [6].

- Make Competent Cells: Prepare competent cells from the model drug-resistant E. coli strain [6].

- Transform CRISPR System: Transform the recombinant CRISPR plasmids (from Part 1) into the competent, drug-resistant E. coli. Plate the transformation on media containing both the CRISPR plasmid antibiotic (e.g., chloramphenicol) and the resistant plasmid antibiotic (tetracycline) [6].

- Screen for Eradication:

- Pick transformant colonies and perform colony PCR using primers flanking the target site within the KPC-2 or IMP-4 gene.

- Successful eradication is indicated by the absence of a PCR product or a size shift. The study reported 100% eradication efficiency for all three systems via this method [6].

- Drug Sensitivity Test: Inoculate eradication-positive colonies into liquid media with the CRISPR plasmid antibiotic but without tetracycline. Perform a disk diffusion or MIC assay with ampicillin. Successful resensitization confirms functional loss of the β-lactamase gene [6].

Part 3: Quantitative Efficiency Comparison (qPCR)

- Extract DNA: Extract total DNA from E. coli cells harboring both the resistant plasmid and the CRISPR plasmid, and from control cells with the resistant plasmid only.

- Perform qPCR: Perform quantitative PCR using primers specific for the resistance gene and a reference gene (e.g., a chromosomal housekeeping gene).

- Analyze Data: Calculate the relative copy number of the resistant plasmid in the CRISPR-containing cells compared to the control. The 2025 study found that CRISPR-Cas3 showed the highest eradication efficiency via this metric, followed by Cas9 and then Cas12f1 [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Plasmids | Delivery of Cas and gRNA genes into cells. | pCas9 (Addgene #42876), pCas3cRh (Addgene #133773) [6]. Often contain mammalian resistance markers (e.g., puromycin) for stable selection. |

| Vector-based Cas | Stable delivery of Cas nuclease via viral vectors. | Lentiviruses, Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). Ideal for long-term expression and hard-to-transfect cells. Market estimated at ~$600M annually [19]. |

| DNA-free Cas Systems | Transient editing with reduced off-target risk. | Cas9-gRNA Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. No DNA integration, higher editing efficiency, favored for therapeutic development [19]. |

| Synthetic gRNAs | Define targeting specificity for the Cas nuclease. | Chemically synthesized sgRNAs. High purity, reduced immune activation in cells compared to in vitro transcription products [16]. |

| Validated Cell Lines | Models for disease research and editing efficiency testing. | Human cell lines (e.g., A549, HEK293). Used in functional validation of gRNAs and Cas variants [20]. |

| Homing Guide RNAs (hgRNAs) | Cellular barcoding and lineage tracing. | gRNAs that include the PAM sequence to target their own DNA, generating diverse mutational profiles to track cell fate [16]. |

The sophisticated interplay between Cas nucleases, guide RNA, and the PAM sequence forms the foundation of CRISPR technology, from its origins in bacterial immunity to its current status as a transformative gene-editing tool. Ongoing research continues to expand the CRISPR toolkit through the discovery of novel systems like Type VII and engineered variants with enhanced precision, flexibility, and safety profiles [13] [14] [18]. For the research and drug development professional, a deep understanding of these core components—their mechanisms, diversity, and quantitative performance—is essential for designing effective experiments and developing the next generation of genetic therapies.

The discovery of CRISPR-Cas systems, adaptive immune mechanisms in bacteria that cleave foreign DNA, has revolutionized genome engineering [21] [22]. At the heart of both bacterial immunity and precision gene editing lies the DNA double-strand break (DSB)—one of the most cytotoxic forms of DNA damage that, if unrepaired, can lead to genomic instability, carcinogenesis, and cell death [23]. Eukaryotic cells have evolved two primary pathways to repair DSBs: the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and the high-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR) [21]. The competitive balance between these pathways is crucial for maintaining genomic integrity and represents a critical determinant for the outcomes of CRISPR-based gene editing [24]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the NHEJ and HDR mechanisms, their regulatory interplay, and their exploitation in therapeutic genome editing, framed within the broader thesis of CRISPR's journey from bacterial immunity to transformative research technology.

Core Mechanisms of NHEJ and HDR

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

NHEJ is the dominant DSB repair pathway in human somatic cells, operating throughout the cell cycle but most prominently in G1 phase [21] [25]. It functions through direct ligation of broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template, making it inherently error-prone but fast and efficient [25].

Key Molecular Steps:

- DSB Recognition: The Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer rapidly binds to exposed DSB ends, protecting them from excessive resection and degradation [23] [25].

- Pathway Activation: DNA-PKcs (DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit) is recruited, forming the DNA-PK holoenzyme that activates downstream signaling [25].

- End Processing: Artemis nuclease processes damaged or incompatible DNA ends. Polymerases μ and λ fill small gaps, while polynucleotide kinase/phosphatase (PNKP) prepares termini for ligation [21].

- Ligation: The XRCC4-DNA Ligase IV complex, stabilized by XLF, catalyzes final ligation [25].

NHEJ is actively suppressed in transcribed genomic regions through RNA-mediated mechanisms. Nascent RNA transcripts can guide repair through RNA-mediated NHEJ (R-NHEJ), where RNA:DNA hybrids form at break sites to facilitate sequence-specific reconstitution of broken ends [25].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

HDR is a precise, template-dependent repair pathway restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when a sister chromatid is available [21]. It utilizes homologous DNA sequences as templates for error-free repair.

Key Molecular Steps:

- 5'-3' DNA End Resection: The MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex initiates resection, generating short 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs. CtIP, BRCA1, EXO1, and DNA2/BLM extend these overhangs to several hundred nucleotides [23].

- RPA Coating: Replication Protein A (RPA) coats ssDNA tails, protecting them from degradation and preventing secondary structure formation.

- RAD51 Nucleoprotein Filament Formation: BRCA2 mediates replacement of RPA with RAD51, forming a helical filament on ssDNA that catalyzes homology search and strand invasion into the sister chromatid or homologous template [23].

- DNA Synthesis and Resolution: DNA polymerase extends the invading strand using the homologous template, followed by resolution of the Holliday junction structure to complete repair.

RNA molecules play underappreciated roles in HDR, serving as structural scaffolds, facilitating repair factor recruitment, and even acting as templates for DNA synthesis via reverse transcriptase activity of DNA polymerase ζ [25].

Table 1: Comparative Features of NHEJ and HDR Pathways

| Feature | NHEJ | HDR |

|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | None (error-prone) | Homologous template (high-fidelity) |

| Primary Catalysts | Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, XRCC4-LigIV | MRN complex, BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51 |

| Cell Cycle Phase | All phases (predominant in G1) | S and G2 phases |

| Repair Fidelity | Low (often introduces indels) | High (precise, error-free) |

| CRISPR Application | Gene knockout via indel mutations | Precise gene correction or insertion |

| Key Inhibitors | 53BP1, RIF1, Shieldin complex | C8orf33 (via H4K16ac regulation) [23] |

| RNA Involvement | RNA bridging, RNA-templated synthesis [25] | RNA-templated repair, hybrid formation [25] |

Pathway Regulation and Choice

The critical decision between NHEJ and HDR pathways is regulated by a complex interplay of cell cycle checkpoints, chromatin modifications, and competitive binding of repair factors at damage sites.

Chromatin and Acetylation Regulation

Histone modifications, particularly histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation (H4K16ac), play a decisive role in repair pathway choice. H4K16ac is predominantly catalyzed by KAT8 (lysine acetyltransferase 8) and creates a chromatin environment that inhibits 53BP1 binding while promoting BRCA1 recruitment, thereby favoring HDR over NHEJ [23].

Recent research has identified C8orf33 as a novel regulator that antagonizes KAT8-mediated H4K16 acetylation at DSB sites. By reducing H4K16ac levels, C8orf33 promotes 53BP1 recruitment and NHEJ while inhibiting DNA end resection and RAD51 accumulation, thereby channeling repair toward NHEJ. Consequently, C8orf33 deficiency enhances HDR activity, leading to increased ribosomal DNA repeat loss and genomic instability [23].

Key Regulatory Competition

The balance between 53BP1 and BRCA1 represents a crucial competition point that determines repair pathway choice. 53BP1 and its downstream effectors (RIF1, shieldin complex) protect DNA ends from resection, promoting NHEJ. In contrast, BRCA1 promotes end resection and counteracts 53BP1, initiating the HDR pathway [23].

Diagram 1: DSB Repair Pathway Regulation

Alternative Repair Pathways

Beyond canonical NHEJ and HDR, alternative repair pathways contribute to DSB repair, particularly in CRISPR editing contexts:

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): Utilizes 2-20 nucleotide microhomologous sequences flanking the break site for alignment, resulting in deletions [24] [25]. Key effector: POLQ (DNA polymerase theta).

- Single-Strand Annealing (SSA): Requires longer homologous sequences (≥30 nt) and deletes intervening sequence. Key effector: Rad52 [24].

- RNA-Templated Repair: Emerging evidence shows RNA molecules can template DSB repair via reverse transcriptase activity of Pol η and Pol θ, challenging the central dogma of DNA-exclusive genetic information transfer [25].

CRISPR Applications and Experimental Methodologies

Exploiting End-Joining for Genome Engineering

CRISPR-based gene knockout strategies predominantly exploit the NHEJ pathway. Following Cas9-induced DSBs, error-prone NHEJ repair introduces insertion/deletion mutations (indels) that disrupt gene function [21]. The efficiency of CRISPR knockouts has been dramatically improved through NHEJ inhibition using compounds like Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2, which increases precise knock-in efficiency by approximately 3-fold (from 5.2% to 16.8% for Cpf1-mediated knock-in and 6.9% to 22.1% for Cas9-mediated knock-in) [24].

Enhancing Precision Editing via HDR

Precise genome editing requires HDR using exogenously supplied donor DNA templates containing desired modifications flanked by homology arms. However, HDR efficiency remains challenging due to competitive dominance of NHEJ and cell cycle dependence.

Advanced HDR Enhancement Strategies:

- NHEJ Pathway Inhibition: Chemical inhibition (e.g., Scr7, Nu7441) or genetic knockdown of core NHEJ factors (Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs) enhances HDR efficiency [24].

- MMEJ and SSA Pathway Suppression: Inhibiting POLQ with ART558 reduces large deletions (≥50 nt) and complex indels, while Rad52 inhibition with D-I03 decreases asymmetric HDR events [24].

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Forcing Cas9 expression in S/G2 phases using geminin- or cyclin B1-derived degrons improves HDR efficiency [21].

- Regulatory Factor Modulation: Depleting C8orf33 enhances HDR by increasing KAT8-mediated H4K16 acetylation, promoting BRCA1 recruitment over 53BP1 [23].

Table 2: Experimental Reagents for Manipulating DSB Repair Pathways

| Reagent | Target Pathway | Mechanism of Action | Application in CRISPR Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | NHEJ inhibitor | Potent chemical inhibition of NHEJ pathway | Increases precise knock-in efficiency ~3-fold [24] |

| ART558 | MMEJ inhibitor | Selective inhibition of POLQ (DNA polymerase theta) | Reduces large deletions and complex indels [24] |

| D-I03 | SSA inhibitor | Specific inhibition of Rad52 annealing activity | Decreases asymmetric HDR and donor mis-integration [24] |

| Cas9-START | Cell cycle regulation | Cas9 fused to geminin-derived degron for S/G2-specific expression | Enhances HDR efficiency by restricting editing to permissive phases |

| C8orf33 siRNA | Regulatory factor | Knockdown enhances KAT8-mediated H4K16ac | Promotes HR over NHEJ by altering chromatin state [23] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery system | Non-viral delivery of CRISPR components | Enables in vivo editing and potential redosing [11] |

DSB Repair Analysis Methodologies

Genotyping Repair Outcomes:

- Long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio) with computational frameworks like knock-knock enables comprehensive classification of repair patterns (perfect HDR, indels, imprecise integration) [24].

- Traffic light reporter (TLR) systems allow simultaneous quantification of HDR and NHEJ efficiencies at defined genomic loci [23].

Functional Assays:

- EJ5-GFP reporter: Quantifies NHEJ integrity and efficiency [23].

- Immunofluorescence for repair factors: Monitoring 53BP1, BRCA1, RAD51, or γH2AX foci formation at damage sites reveals pathway utilization [23] [26].

- Spatio-temporal analysis frameworks: Live imaging of tumor spheroids via Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy with DNA damage sensors (e.g., mCherry-53BP1) generates quantitative maps of DSB repair dynamics in 3D microenvironments [26].

Diagram 2: DSB Repair Analysis Workflow

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

The manipulation of DSB repair pathways has enabled groundbreaking clinical applications. Casgevy, the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia, utilizes ex vivo HDR-mediated editing of hematopoietic stem cells [11] [21]. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of NHEJ-mediated gene disruption for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), with lipid nanoparticle-delivered CRISPR achieving ~90% reduction in disease-causing TTR protein levels sustained over two years [11].

Emerging strategies include:

- In vivo base editing: CRISPR components delivered via LNPs to correct point mutations without inducing DSBs, avoiding repair pathway competition altogether [21].

- Prime editing: Utilizes reverse transcriptase activity to write genetic information directly into target sites using RNA templates, harnessing cellular repair mechanisms similar to natural RNA-templated repair [25].

- Immuno-oncology applications: DDR gene mutations influence tumor immunogenicity and response to checkpoint inhibitors. BRCA-deficient tumors exhibit enhanced neoantigen presentation and improved response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapies [27].

The intricate balance between NHEJ and HDR pathways represents a fundamental cellular process that maintains genomic stability while creating evolutionary flexibility. The journey from understanding bacterial CRISPR immunity to harnessing these mechanisms for precision genome editing has revealed the profound complexity of DSB repair regulation. As we continue to elucidate the nuanced interplay between chromatin modifications, repair factor competition, and RNA-mediated processes, new opportunities emerge for increasingly sophisticated control over repair outcomes. The strategic modulation of these pathways—through chemical inhibition, temporal control, or regulatory factor manipulation—will undoubtedly unlock new therapeutic possibilities and further cement CRISPR-based technologies as transformative tools in biomedical research and clinical medicine.

From Lab to Clinic: Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Trial Progress

Ex Vivo vs. In Vivo Editing Approaches

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology represents a transformative breakthrough in genetic engineering, repurposing an ancient bacterial immune system into a precise gene-editing tool. First discovered in bacterial immune systems and described in the seminal 2012 publication by Dr. Jennifer Doudna and Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier, the CRISPR-Cas system originated as a defense mechanism that bacteria use to cut and disable invading bacteriophage DNA [28]. This natural system comprises two key components: a guide RNA (gRNA) sequence that directs the CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease to a specific target DNA sequence, and the Cas nuclease itself that creates the double-stranded break in the DNA [28]. The repurposing of this bacterial immune mechanism into a programmable gene-editing tool earned Doudna and Charpentier the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and launched a new era in genetic medicine [28].

As CRISPR technologies have evolved from basic research tools to therapeutic applications, two primary delivery approaches have emerged: ex vivo and in vivo gene editing. These approaches represent fundamentally different strategies for implementing genetic modifications, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and technical considerations. This review provides a comprehensive technical comparison of ex vivo and in vivo editing approaches, examining their underlying mechanisms, current applications, methodologies, and future directions in therapeutic development.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Definitions

Ex Vivo Gene Editing

Ex vivo gene editing involves extracting cells from a patient, genetically modifying them outside the body using CRISPR technology, and then reinfusing the edited cells back into the patient [28]. This approach essentially transforms the patient's own cells into living therapies that have been engineered for specific therapeutic purposes. The most prominent example of ex vivo editing is exagamglogene autotemcel (exa-cel), marketed as Casgevy, which received regulatory approval for treating sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia [28]. This therapy involves harvesting hematopoietic stem cells from the patient, editing them using CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the BCL11A gene enhancer, thereby increasing fetal hemoglobin production, and reinfusing them after the patient receives conditioning chemotherapy to clear bone marrow space [28].

In Vivo Gene Editing

In vivo gene editing occurs when the instructions for the CRISPR gene editor are injected directly into a patient, where the editing components navigate to the target cells and perform genetic modifications inside the body [28] [11]. This approach utilizes various delivery vehicles, most commonly recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors or lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), to transport CRISPR components to specific tissues [29]. A landmark example of in vivo editing is the personalized CRISPR treatment developed for an infant with CPS1 deficiency, where lipid nanoparticles delivered the editing machinery directly to the patient's cells via intravenous infusion [11]. This case demonstrated the potential for rapid development of bespoke in vivo therapies for rare genetic conditions.

Technical Comparison and Clinical Applications

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ex Vivo and In Vivo Editing Approaches

| Parameter | Ex Vivo Editing | In Vivo Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Cells edited outside the body and reinfused | Genetic editing occurs inside the body |

| Delivery Method | Electroporation, chemical transfection of extracted cells | Viral vectors (rAAV), Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) |

| Therapeutic Examples | Casgevy (SCD, TDT), CAR-T cells | EDIT-101 (LCA10), hATTR therapy |

| Key Advantages | Precise control over editing conditions; Lower immunogenicity risk; Ability to select and validate edited cells | Less invasive; Potential to target inaccessible tissues; Broader applicability |

| Major Challenges | Complex manufacturing; High cost; Requires cell transplantation | Delivery efficiency; Immune responses; Limited packaging capacity |

| Editing Efficiency | High (can be validated pre-infusion) | Variable (depends on delivery and tissue targeting) |

| Manufacturing Complexity | High (requires GMP cell processing facilities) | Medium (biological manufacturing of vectors) |

| Therapeutic Durability | Potentially lifelong (with stem cell editing) | May require redosing (LNPs allow this) |

Table 2: Current Clinical Applications and Trial Status

| Disease Area | Ex Vivo Approach | In Vivo Approach | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Disease | Casgevy (approved) | N/A | Market approval [28] |

| Beta-Thalassemia | Casgevy (approved) | N/A | Market approval [28] |

| hATTR | N/A | NTLA-2001 (Intellia) | Phase III [11] |

| Hereditary Angioedema | N/A | Intellia program | Phase I/II [11] |

| Leber Congenital Amaurosis | N/A | EDIT-101 | Phase I/II [29] |

| Autoimmune Diseases | Multiple programs (CRISPR Therapeutics) | N/A | Phase I/II [30] |

| Oncology | CAR-T cell therapies | N/A | Multiple Phase I/II [30] |

The clinical trial landscape for CRISPR therapies has expanded dramatically, with approximately 250 clinical trials involving gene-editing therapeutic candidates currently tracked, more than 150 of which are active as of February 2025 [30]. These span multiple therapeutic areas including blood disorders, cancers, infectious diseases, metabolic disorders, and rare genetic conditions [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Ex Vivo Editing Workflow

The standard protocol for ex vivo gene editing involves multiple meticulously controlled steps:

- Cell Collection: Apheresis is performed to collect target cells (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells, T cells) from the patient [28].

- Cell Processing and Activation: Cells are processed and activated to make them receptive to genetic modification.

- CRISPR Delivery: CRISPR components (Cas protein and guide RNA) are introduced into the isolated cells via electroporation, which uses electrical pulses to create temporary pores in cell membranes [31].

- Editing Verification: A sample of edited cells is analyzed using methods like Sanger sequencing, next-generation sequencing, or functional assays to confirm editing efficiency and specificity [32].

- Cell Expansion: Successfully edited cells are expanded in culture to achieve therapeutic quantities.

- Patient Conditioning: The patient receives conditioning chemotherapy (e.g., busulfan) to create space in the bone marrow for the edited cells [28].

- Reinfusion: The engineered cells are infused back into the patient where they engraft and produce the therapeutic effect.

In Vivo Editing Workflow

In vivo editing follows a different pathway that relies on sophisticated delivery systems:

- Vector Production: CRISPR-Cas system is packaged into delivery vehicles. For rAAV vectors, this involves plasmid transfection into producer cells; for LNPs, CRISPR mRNA and gRNA are encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles [29].

- Quality Control: Vector products undergo rigorous testing for potency, purity, and safety.

- Administration: The formulated CRISPR therapeutic is administered directly to the patient via route appropriate to the target tissue (e.g., intravenous injection, subretinal injection) [29].

- Cellular Uptake: Delivery vehicles are taken up by target cells through endocytosis or membrane fusion.

- Component Release and Editing: CRISPR components are released into the cytoplasm and traffic to the nucleus where genome editing occurs.

- Therapeutic Effect Assessment: Patients are monitored for editing efficiency (e.g., through biomarker changes) and therapeutic outcomes.

In Vivo CRISPR Workflow

Delivery Systems and Vector Engineering

Viral Vector Systems for In Vivo Delivery

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors have emerged as prominent vehicles for in vivo CRISPR delivery due to their favorable safety profile, high tissue specificity, and ability to induce sustained transgene expression [29]. However, their limited packaging capacity (<4.7 kb) presents significant challenges for delivering larger CRISPR components. Several innovative strategies have been developed to overcome this limitation:

- Compact Cas Orthologs: Utilization of smaller Cas proteins such as Campylobacter jejuni Cas9 (CjCas9), Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9), and the ultra-compact Cas12f enable packaging into single rAAV vectors [29].

- Dual rAAV Vector Systems: Splitting CRISPR components across two separate rAAV vectors that recombine inside target cells to reconstitute functional editing machinery [29].

- Trans-splicing rAAV Vectors: Employing intein-mediated protein trans-splicing to reassemble split Cas proteins after delivery [29].

Recent advances have identified even smaller effectors such as IscB and TnpB, putative ancestors of modern Cas proteins, as promising tools for ultra-compact genome editing due to their small molecular size and potentially reduced immunogenicity [29].

Non-Viral Delivery Systems

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as a powerful alternative to viral delivery systems, particularly for liver-directed therapies. LNPs are tiny lipid particles that naturally form droplets around CRISPR components and have a natural affinity for liver cells when delivered systemically [11]. A significant advantage of LNPs is their reduced immunogenicity compared to viral vectors, which enables redosing - as demonstrated in the cases of the hATTR trial and the personalized CPS1 deficiency treatment where patients safely received multiple doses [11].

CRISPR Delivery System Classification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9, SaCas9, CjCas9, Cas12a | DNA cleavage enzymes with different PAM requirements and sizes |

| Base Editors | BE4max, ABE8e | Catalyze specific base conversions without double-strand breaks |

| Prime Editors | PE2, PEmax | Enable precise insertions, deletions, and all base-to-base conversions |

| Delivery Vehicles | rAAV serotypes, LNPs, Electroporation systems | Transport CRISPR components into target cells |

| Control gRNAs | TRAC, RELA, ROSA26 (mouse) | Validated positive controls for editing efficiency [32] |

| Validation Tools | ICE Analysis, NGS assays, T7E1 assay | Assess editing efficiency and specificity |

| Cell Culture Media | Stem cell media, T-cell activation media | Support maintenance and expansion of primary cells |

When planning CRISPR experiments, researchers must select appropriate controls to validate their findings. Essential controls include:

- Positive Editing Controls: Validated guide RNAs targeting standard genomic regions (e.g., TRAC, RELA in human cells; ROSA26 in mouse models) that demonstrate high editing efficiencies and confirm optimized workflow conditions [32].

- Negative Editing Controls: Include scramble guide RNAs with no genomic targets, guide RNA only (no Cas nuclease), or Cas nuclease only (no guide RNA) to establish baseline cellular responses to transfection stress [32].

- Transfection Controls: Fluorescence reporters (e.g., GFP mRNA) to visualize and quantify delivery efficiency into target cells [32].

- Mock Controls: Cells subjected to transfection conditions without any CRISPR components to distinguish true editing phenotypes from cellular stress responses [32].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Technical and Manufacturing Challenges

Both ex vivo and in vivo approaches face significant technical hurdles. For ex vivo therapies, the complex manufacturing process requiring specialized facilities and the high costs present barriers to widespread accessibility [28]. Additionally, the conditioning chemotherapy needed for stem cell engraftment carries significant toxicity risks [28].

For in vivo approaches, delivery efficiency remains a primary challenge, with limited tissue targeting capabilities beyond the liver [11] [29]. Immune responses to CRISPR components or delivery vehicles can reduce efficacy and prevent redosing, particularly with viral vectors [29]. The limited packaging capacity of preferred viral vectors also restricts the size of CRISPR machinery that can be delivered [29].

Financial and Regulatory Landscape

The CRISPR medicine landscape has shifted significantly in recent years, with market forces reducing venture capital investment in biotechnology [11]. This has led companies to narrow their pipelines and focus on getting a smaller set of products to market more quickly rather than creating broader therapeutic pipelines [11]. Additionally, the first half of 2025 saw major cuts in US government funding for basic and applied scientific research, potentially slowing the development of new therapies in the future [11].

Future Directions

Despite these challenges, the field continues to advance with several promising developments:

- Redosing Capabilities: The demonstration that LNP-delivered CRISPR therapies can be safely redosed opens new possibilities for titrating editing levels and addressing diseases requiring multiple treatments [11].

- Personalized Therapies: The successful development of a bespoke CRISPR treatment for a single patient with CPS1 deficiency in just six months establishes a precedent for rapid development of personalized in vivo therapies for rare genetic conditions [11].

- Expanded Delivery Options: Research continues on creating LNPs with affinity for organs beyond the liver and improving viral vector targeting capabilities [11].

- Novel Editing Platforms: The exploration of compact ancestral effectors like IscB and TnpB may lead to more efficient delivery and reduced immunogenicity [29].

The evolution of CRISPR from a bacterial immune mechanism to a powerful gene-editing technology has opened transformative possibilities for treating genetic diseases. Both ex vivo and in vivo editing approaches have demonstrated remarkable clinical successes, from the approved ex vivo therapy Casgevy for hemoglobinopathies to the pioneering in vivo treatments for hATTR and rare genetic conditions. The choice between ex vivo and in vivo approaches depends on multiple factors including the target tissue, disease pathophysiology, manufacturing capabilities, and therapeutic goals.

As the field advances, key challenges remain in improving delivery efficiency, reducing immunogenicity, expanding tissue targeting, and making these innovative therapies more accessible. The ongoing development of more compact editors, improved delivery vehicles, and personalized approaches promises to expand the therapeutic landscape and bring CRISPR-based treatments to more patients with genetic diseases.

The journey of CRISPR from a fundamental bacterial immune system to a revolutionary clinical tool represents a paradigm shift in biomedical science. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and their associated proteins (Cas) function as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, protecting against viral invaders by capturing and storing fragments of foreign DNA. This natural system has been harnessed into a precise genome-editing technology that is now delivering therapeutic breakthroughs across multiple disease areas [21]. As of February 2025, the CRISPR clinical landscape encompasses approximately 250 clinical trials involving gene-editing therapeutic candidates, with more than 150 trials currently active, spanning hematologic, metabolic, and infectious diseases [30]. This technical guide examines the key therapeutic applications, experimental methodologies, and clinical progress of CRISPR-based interventions in these three pivotal areas.

Hematologic Diseases

Clinical Landscape and Therapeutic Approaches

CRISPR-based therapies for hematologic diseases have led the clinical translation of gene editing, with the first approved CRISPR therapy, CASGEVY (exagamglogene autotemcel), now approved for both sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT) [30] [11]. The therapeutic strategy primarily involves ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or T-cells followed by reinfusion into patients.

Table 1: Key CRISPR Clinical Trials in Hematologic Diseases

| Indication | Therapy/Candidate | Editing Approach | Phase | Key Target | Sponsor/Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Disease & Beta Thalassemia | CASGEVY | ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 | Approved | BCL11A enhancer | CRISPR Therapeutics/Verve |

| B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (B-ALL) | N/A | ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 | I/II | CD19 | Servier, Great Ormond Street Hospital |

| Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) | N/A | ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 | I | Multiple | Intellia Therapeutics |

| B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) | N/A | ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 | I/II | CD19 | Bioray Laboratories, Precision BioSciences |

| Multiple Myeloma | N/A | ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 | I | BCMA | University of Pennsylvania, Fate Therapeutics |

| Relapsed/Refractory B-cell Malignancies | N/A | ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 | I | CD19 | Chinese PLA General Hospital |

The majority of Phase 3 trials in the gene editing field continue to focus on hematologic disorders, particularly sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia [30]. Beyond these monogenic blood disorders, the field has expanded to include hematologic malignancies, with approaches focusing on engineering immune cells to enhance their anti-tumor capabilities.

Key Experimental Protocols

Ex Vivo HSC Editing for Hemoglobinopathies:

- HSC Collection: CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells are collected from patient via apheresis following mobilization [11]

- Electroporation: Cells are transfected with CRISPR-Cas9 components (typically as ribonucleoprotein complexes) via electroporation [33]

- Targeted Editing: The BCL11A enhancer is targeted to disrupt the repressive binding that suppresses fetal hemoglobin production [11]

- Myeloablative Conditioning: Patients receive busulfan conditioning to clear bone marrow niche

- Reinfusion: Edited cells are infused back into the patient where they engraft and reconstitute hematopoiesis

- Validation: Editing efficiency is confirmed using NGS-based methods (ICE analysis or targeted NGS) [34]

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell Engineering:

- T-cell Isolation: T-cells are collected from patient via leukapheresis

- CRISPR-Mediated Knockout: Endogenous T-cell receptor genes (TRAC, TRBC) and/or HLA genes are disrupted to reduce graft-versus-host disease potential [30]

- CAR Integration: A CAR transgene is integrated into a specific genomic locus using HDR

- Expansion: Engineered CAR T-cells are expanded ex vivo

- Lymphodepletion: Patient receives lymphodepleting chemotherapy

- Infusion: CAR T-cells are administered to patient

- Quality Control: Multiplex qPCR and flow cytometry assess CAR expression and phenotype

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hematologic Disease Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Method | Neon Transfection System, Nucleofector | Electroporation for ex vivo editing of HSCs and primary T-cells |

| CRISPR Nuclease | High-fidelity Cas9, Cas12a variants | Improved specificity for clinical applications |

| Stem Cell Media | StemSpan, ImmunoCult | Maintenance and expansion of hematopoietic stem cells |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | SCF, TPO, FLT3-L, IL-3, IL-6, IL-7, IL-15 | Support differentiation and expansion of blood lineages |

| Analysis Tools | ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits), TIDE, NGS | Quantification of editing efficiency and specificity |

Figure 1: Ex Vivo CRISPR Workflow for Hematologic Diseases

Metabolic Diseases

Clinical Landscape and Therapeutic Approaches

Metabolic diseases represent a rapidly advancing area for CRISPR therapeutics, particularly with the development of in vivo delivery systems, most notably lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that preferentially target the liver [11] [33]. The liver's central role in metabolism and the efficiency of LNP-mediated delivery have enabled successful clinical programs for multiple metabolic disorders.

Table 3: Key CRISPR Clinical Trials in Metabolic Diseases

| Indication | Therapy/Candidate | Editing Approach | Phase | Key Target | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR) | NTLA-2001 | in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 LNP | III | TTR | Intellia Therapeutics |

| Hereditary Angioedema (HAE) | NTLA-2002 | in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 LNP | I/II | KLKB1 | Intellia Therapeutics |

| Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) | VERVE-101, VERVE-102 | in vivo Base Editing LNP | Ib | PCSK9 | Verve Therapeutics |

| Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) | VERVE-201 | in vivo Base Editing LNP | Ib | ANGPTL3 | Verve Therapeutics |

| Severe Hypertriglyceridemia | CTX310 | in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 LNP | I | ANGPTL3 | CRISPR Therapeutics |

| High Lipoprotein(a) | CTX320 | in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 LNP | I | Lp(a) gene | CRISPR Therapeutics |

| CPS1 Deficiency | Bespoke Therapy | in vivo Base Editing LNP | Case Study | CPS1 | CHOP/Penn |

A landmark case reported in 2025 demonstrated the potential for personalized CRISPR therapeutics for ultra-rare metabolic diseases. An infant with severe carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency was treated with a bespoke base editing therapy developed and delivered in just six months [35]. This case establishes a regulatory and manufacturing precedent for personalized gene editing approaches.

Key Experimental Protocols

In Vivo LNP Delivery for Liver-Targeted Metabolic Diseases:

- LNP Formulation: CRISPR-Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA are encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles optimized for hepatic delivery [11]

- Dose Determination: Preclinical studies in non-human primates establish effective dosing ranges [36]

- Administration: LNPs are administered via intravenous infusion

- Hepatocyte Transfection: LNPs are taken up by hepatocytes, releasing CRISPR components

- Target Gene Modification: Cas9 induces DSBs in the target gene (e.g., TTR, PCSK9, ANGPTL3)

- Therapeutic Effect: Reduction in pathogenic protein levels measured in serum

- Safety Monitoring: Assessment of liver enzymes, off-target effects, and immune response

Personalized Therapy Development (as demonstrated for CPS1 deficiency):

- Variant Identification: Specific disease-causing mutation identified via clinical sequencing [35]

- gRNA Design: Guide RNA designed to target the specific pathogenic variant

- Editor Selection: Appropriate base editor chosen based on required nucleotide change

- LNP Manufacturing: GMP-compliant production of bespoke LNP formulation

- Preclinical Validation: Editing efficiency and safety assessed in relevant cell models

- Regulatory Approval: IND application submitted to FDA under emergency use pathway

- Clinical Administration: Multiple LNP doses administered via IV infusion with monitoring

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Disease Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Vehicle | LNP formulations, GalNAc-LNPs, AAV | In vivo delivery to hepatocytes |

| Editor Platform | ABE, CBE, Prime Editors | Precise nucleotide conversion without DSBs |

| Animal Models | Non-human primates, humanized mice | Preclinical efficacy and safety testing |

| Biomarker Assays | ELISA, MSD, SIMOA | Quantification of protein reduction in serum |

| Off-Target Assessment | CHANGE-seq, GUIDE-seq, ONE-seq | Genome-wide identification of off-target edits |

Figure 2: In Vivo LNP Delivery Pathway for Metabolic Liver Diseases

Infectious Diseases

Clinical Landscape and Therapeutic Approaches

CRISPR applications in infectious diseases leverage the technology's origins as an adaptive immune system, deploying it against human pathogens through multiple mechanisms: direct pathogen targeting, host factor manipulation, and engineering of therapeutic cells [37].

Table 5: Key CRISPR Clinical Trials in Infectious Diseases

| Indication | Therapy/Candidate | Editing Approach | Phase | Key Target | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Infections | crPhage Cocktail | CRISPR-Cas3 Engineered Bacteriophage | I/II | E. coli genomic sequences | SNIPR Biome |

| Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) | crPhage Cocktail | CRISPR-Cas3 Engineered Bacteriophage | I/II | E. coli genomic sequences | Locus Biosciences |

| HIV-1 | EBT-101 | in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 AAV | I | HIV Proviral DNA | Excision BioTherapeutics |

| HPV-associated Cancer | N/A | in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 LNP | Preclinical | E6/E7 oncogenes | Multiple |