Overcoming Mosaicism in CRISPR-Edited Organisms: Strategies for Reliable Gene Editing in Research and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of genetic mosaicism, a prevalent challenge that reduces the efficiency and reliability of CRISPR-based gene editing in both model organisms and therapeutic applications.

Overcoming Mosaicism in CRISPR-Edited Organisms: Strategies for Reliable Gene Editing in Research and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of genetic mosaicism, a prevalent challenge that reduces the efficiency and reliability of CRISPR-based gene editing in both model organisms and therapeutic applications. We explore the fundamental mechanisms by which mosaicism arises when edits occur asymmetrically after the first embryonic cell division. The review systematically evaluates current methodologies to minimize mosaicism, including the optimization of CRISPR editor formats, delivery methods, and the timing of editing events. Furthermore, we discuss advanced screening strategies and alternative technologies that circumvent the production of mosaic offspring. Finally, the article synthesizes validation techniques and comparative analyses of different CRISPR systems, offering a troubleshooting and optimization guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to achieve consistent, heritable genetic modifications.

Understanding Mosaicism: Defining the Challenge in CRISPR-Edited Organisms

What is Genetic Mosaicism? Definition and Impact on Experimental and Breeding Outcomes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is genetic mosaicism?

Genetic mosaicism is the condition in which a single multicellular organism possesses two or more genetically distinct cell lineages. These different cell lines all originate from a single fertilized egg (zygote), but acquire genetic differences due to mutations that happen after fertilization, a process known as post-zygotic mutation [1] [2].

What is the difference between somatic and germline mosaicism?

- Somatic Mosaicism: The genetic variation is present in somatic (body) cells but not in the germ cells (sperm or oocytes). This type of mosaicism can affect the individual's health but is not passed on to their offspring [1] [2].

- Germline Mosaicism: The genetic variation is present specifically in the germ cells. The individual may not be affected, but they can pass the mosaicism on to their offspring, potentially causing genetic disease in the next generation [1].

Why is mosaicism a major concern in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing?

In CRISPR-Cas9 editing, mosaicism is a frequent challenge where an organism develops with a mixture of edited and unedited cells [3]. This occurs because the editing process may not complete before the embryo begins its initial cell divisions. If the CRISPR machinery remains active and edits DNA in only some cells of a multicellular embryo, it results in a mosaic organism [4] [3]. This is problematic for research and breeding because:

- It leads to inconsistent presentation of the desired trait.

- The intended edit might be absent from the germline, meaning it cannot be passed to future generations [3].

How can I reduce the incidence of mosaicism in my CRISPR experiments?

Several strategies are being refined to tackle mosaicism, focusing on four key areas [3]:

- CRISPR-Cas9 Format: Using alternative formats like ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes instead of plasmid DNA can speed up editing as they are active immediately upon delivery.

- Timing and Delivery: Optimizing the method and timing of delivery (e.g., microinjection or electroporation) to ensure editing occurs at the single-cell zygote stage before DNA replication and division.

- Editor Type: Employing advanced Cas9 variants, such as base editors or prime editors, which can cause more precise and efficient edits without relying on the cell's error-prone repair pathways.

- Small Molecule Enhancers: Using small molecules that inhibit non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or promote homology-directed repair (HDR) can improve the efficiency of precise edits and reduce mosaic outcomes [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Managing Mosaicism in Your Experiments

Mosaicism can confound experimental results and lead to non-reproducible data. The flowchart below outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and managing this issue.

Steps to take:

- Confirm the Problem: If you observe a weak, variable, or absent phenotype in a founder organism, suspect mosaicism. Genotype multiple tissue samples (e.g., ear clip, liver, blood) from the same animal. Finding different genotypes across tissues confirms mosaicism [3].

- Assess Experimental Impact: Determine if the level and distribution of edited cells are sufficient for your experimental goals. For some somatic studies, a specific tissue with high editing may be usable.

- Check the Germline: This is critical for breeding projects. Cross the mosaic founder (F0) with a wild-type animal. Genotype the offspring (F1). If no F1 animals carry the edit, the founder's germline was not edited, and you cannot establish a stable line [3].

- Decision Point:

- If the germline is edited, you can proceed to breed the F1 generation to establish a stable, non-mosaic line for future experiments.

- If the germline is not edited, you must return to the experimental design phase and implement strategies to reduce mosaicism, such as those listed in the FAQs above.

Quantitative Impact of Mosaicism in Embryonic Development

The table below summarizes key data on how mosaicism detected during Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy (PGT-A) affects clinical outcomes, illustrating the potential for developmental impairment. This data is highly relevant for researchers working with early-stage embryos.

Table 1: Embryo Transfer Outcomes: Euploid vs. Mosaic

| Outcome Measure | Euploid Embryos | All Mosaic Embryos | Whole-Chromosome Mosaic Embryos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implantation Rate | 57.2% [5] | 46.5% [5] | 41.8% [5] |

| Ongoing Pregnancy / Live Birth Rate | 52.3% [5] | 37.0% [5] | 31.3% [5] |

| Spontaneous Abortion Rate | 8.6% - 8.9% [5] [6] | 20.4% [5] | 25.0% - 27.6% [5] [6] |

| Likelihood of Healthy Live Birth | Highest | Intermediate | Lowest among mosaic types [5] |

Prioritizing Mosaic Embryos for Transfer in Research Models

For researchers using model organisms where embryo transfer is necessary, the following ranking system, adapted from clinical studies, can help prioritize mosaic embryos with the best potential for development.

Table 2: Mosaic Embryo Transfer Priority Guide

| Priority Tier | Mosaic Level | Chromosome Type / Number | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low-level (<50% aneuploid cells) [5] [7] | Single, segmental abnormalities [5] | Outcomes most similar to euploid embryos. Lower risk of miscarriage [7]. |

| Medium | Low-level (<50% aneuploid cells) [5] | Specific whole chromosomes (e.g., 1, 3, 10, 12, 19) [7] | Associated with lower risk of adverse outcomes based on prenatal data [7]. |

| Low | High-level (≥50% aneuploid cells) [5] [7] | Multiple (complex) aneuploidies [5] | Significantly reduced implantation and pregnancy rates; high miscarriage risk [5] [7]. |

| Avoid | Any level | Specific high-risk chromosomes (e.g., 13, 16, 18, 21) [7] | High risk of nonviable birth or severe congenital disorders [7]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Overcoming Mosaicism

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Reducing Mosaicism | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-formed complex of Cas9 protein and gRNA. Edits immediately upon delivery, reducing the window for post-division editing [3]. | Microinjection or electroporation of RNP into zygotes. |

| Base Editors / Prime Editors | Advanced editors that directly convert one base to another or insert small sequences without causing a double-strand break, leading to more precise and efficient editing with lower mosaic rates [3]. | Used for introducing point mutations or small insertions with high fidelity. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers (e.g., RS-1) | Modulate DNA repair pathways. RS-1 stimulates Rad51 to promote Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) over error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) [3]. | Added to embryo culture media after CRISPR injection to boost precise editing. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | High-resolution genetic screening to detect and quantify the level of mosaicism in embryos or founder animals [8] [3]. | Used for rigorous genotyping of multiple tissues to confirm and assess mosaicism. |

| Single-Cell Cloning | A method to isolate a single, uniformly edited cell from a mosaic population, which can then be expanded into a non-mosaic cell line [4]. | Common in cell culture work to establish pure clonal lines after CRISPR editing. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is genetic mosaicism in the context of CRISPR-edited embryos? Genetic mosaicism occurs when a CRISPR-edited embryo contains a mixture of cells with different genotypes (more than two unique alleles) instead of a uniform edit across all cells. This is a common phenomenon when CRISPR components are active after the zygote has begun its cell divisions. [9] [10]

2. Why is asymmetric editing a primary cause of mosaicism? Asymmetric editing refers to the phenomenon where the paternal and maternal genomes in a zygote are edited at different times and with different efficiencies. The paternal genome, which undergoes rapid chromatin decondensation after fertilization, is often edited as an early event, before DNA replication. In contrast, the maternal genome is typically edited later, after the first round of DNA replication (S-phase). This temporal disparity means that edits to the maternal genome can result in a mixture of edited and unedited cells within the same embryo, leading to mosaicism. [11]

3. How does the timing of CRISPR delivery impact mosaicism? The point in the cell cycle when CRISPR components are delivered is a critical factor. Delivering CRISPR after the zygote has already started DNA replication drastically increases the risk of mosaicism. [9]

Table: Impact of Microinjection Timing on Mosaicism in Bovine Embryos

| Microinjection Protocol | Description | Reported Mosaicism Rate in Edited Embryos |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional (20 hpi) | Microinjection at 20 hours post-insemination | ~100% [9] |

| Early Zygote (10 hpi) | Microinjection at 10 hours post-insemination | ~30% [9] |

| Oocyte (0 hpi) | Microinjection of oocyte before fertilization | ~10-30% [9] |

Abbreviation: hpi, hours post-insemination.

4. What are the practical consequences of mosaicism in research? Mosaicism complicates genotype-phenotype correlation because a single animal has multiple cell populations with different genetic makeups. This reduces the odds of generating a complete knock-out (KO) animal in a single step, as the embryo may still contain unedited (wild-type) alleles. It also makes germline transmission in founder animals unpredictable, requiring extensive breeding to establish stable lines. [9] [10]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Rates of Mosaicism in Founder Embryos

Potential Cause #1: Late delivery of CRISPR components. If microinjection is performed after the zygote has already initiated DNA replication (S-phase), the editing machinery may only act on some of the replicated DNA copies, leading to multiple alleles in different daughter cells. [9]

- Solution: Implement early microinjection protocols.

- Protocol: Oocyte Microinjection (before fertilization): Inject the CRISPR components directly into the metaphase II (mII) oocyte, followed by fertilization via Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI). This pre-loading strategy ensures components are present at the earliest possible stage of the gamete-to-embryo transition. [11] [9]

- Protocol: Early Zygote Microinjection: Shorten the in-vitro fertilization (IVF) window and perform microinjection shortly after fertilization (e.g., 10 hpi), before the majority of zygotes enter S-phase. [9]

Potential Cause #2: Using less stable CRISPR formats. The format of the CRISPR components can affect how quickly and efficiently they act once inside the embryo.

- Solution: Use Cas9 pre-complexed with chemically modified guide RNAs as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP).

- Detailed Methodology: The use of Cas9 RNPs, where the Cas9 protein is pre-assembled with the guide RNA, leads to faster editing and reduced off-target effects. Chemically synthesized guide RNAs with stability-enhancing modifications (e.g., 2’-O-methyl at terminal residues) are more stable and can reduce immune stimulation in some models. Injecting RNP complexes into oocytes or early zygotes has been shown to achieve high editing efficiency while significantly reducing mosaicism. [12] [9]

Problem: Inaccurate Genotyping Due to Complex Edits

Potential Cause: Standard genotyping methods fail to detect large deletions. Common techniques like subcloning followed by Sanger sequencing may not reveal the full spectrum of edits, particularly large deletions or complex alleles present in a mosaic embryo, leading to misclassification of embryos as wild-type. [13]

- Solution: Employ long-read single-molecule sequencing for genotyping.

- Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Extraction & PCR: Isolate genomic DNA from embryonic tissue (e.g., yolk sac). Perform a long-range PCR to generate an amplicon of several kilobases surrounding the CRISPR target site.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the PCR product and run it on a long-read sequencing platform, such as Oxford Nanopore.

- Data Analysis: Use specialized software pipelines (e.g., CRISPResso2) to align sequences to a wild-type reference genome and identify the full spectrum of insertion or deletion (INDEL) events, including large deletions up to 3 kb or more. This method is crucial for accurate genotype-phenotype correlations in F0 generation CRISPants. [13]

- Detailed Protocol:

Experimental Workflows for Mosaicism Reduction

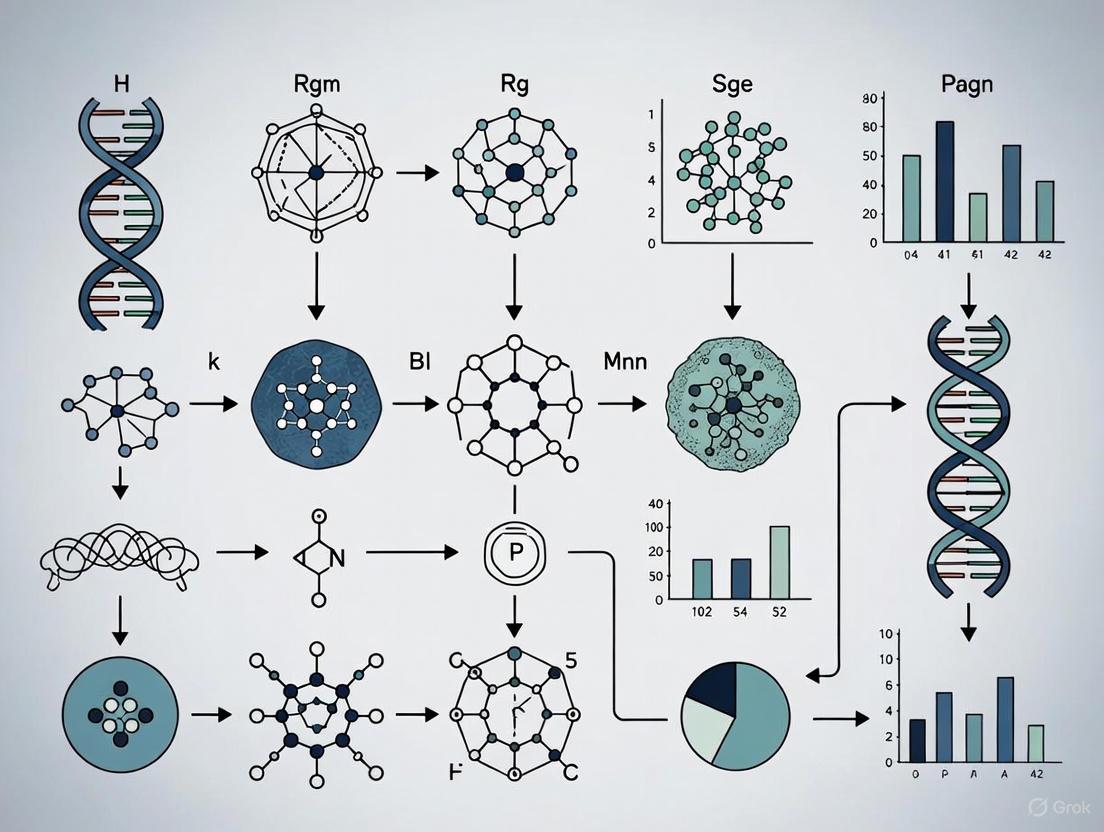

The following diagram illustrates two key early-delivery protocols designed to minimize mosaicism by ensuring CRISPR components are present before DNA replication begins.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for CRISPR Embryo Editing and Mosaicism Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Synthetic guide RNA with molecular modifications (e.g., 2’-O-methyl) to enhance stability and editing efficiency. | Reduces degradation by cellular RNases and can lower immune stimulation, leading to more consistent activity. [12] |

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | The Cas9 endonuclease enzyme. Used to form Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. | RNP delivery leads to rapid editing, high efficiency, and can reduce off-target effects compared to plasmid-based methods. [12] [9] |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) | An enzyme used in mismatch cleavage assays to estimate genome editing efficiency. | A convenient method for initial efficiency screening, but it does not provide detailed sequence information on the resulting indels. [12] |

| 5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) | A thymidine analog used to detect and track DNA replication (S-phase) in cells. | Crucial for characterizing the timing of DNA replication in zygotes to optimize injection windows and reduce mosaicism. [9] |

| Long-Range PCR Kit | A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system designed to amplify long segments of DNA (several kilobases). | Essential for preparing amplicons that encompass large potential deletion regions for long-read sequencing. [13] |

Mechanism of Asymmetric Genome Editing

The diagram below outlines the cellular mechanism that leads to asymmetric editing of parental genomes, a root cause of mosaicism.

Despite the significant challenge of genetic mosaicism, direct zygote editing via CRISPR-Cas9 is often preferred over Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) for generating gene-edited livestock and animal models. SCNT, which involves editing cells in culture before nuclear transfer, produces non-mosaic offspring but is hampered by low efficiency, high technical demands, and cost [3] [14]. Direct zygote editing, while frequently resulting in mosaic founders (individuals with multiple cell genotypes), offers a simpler, more rapid protocol that is more practical for widespread integration into breeding programs [3] [15]. This technical support center outlines the core reasons for this preference and provides researchers with targeted FAQs and troubleshooting guides to directly overcome the hurdle of mosaicism, thereby improving the efficiency of this promising technique.

Core Comparison: SCNT vs. Direct Zygote Editing

The table below summarizes the fundamental technical and practical differences between the two primary methods for generating gene-edited animals.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of SCNT versus Direct Zygote Editing

| Feature | Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | Direct Zygote Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Gene editing is performed on somatic cells in culture, followed by transfer of a selected nucleus into an enucleated oocyte [3] [14]. | CRISPR-Cas9 reagents are introduced directly into a fertilized zygote to edit the genome in situ [3] [15]. |

| Mosaicism | Not present. The animal develops from a single, validated genome, ensuring uniformity [3]. | Common. Editing often continues after the first cell division, leading to multiple genotypes in a single individual [3] [15]. |

| Efficiency & Practicality | Technically demanding, low efficiency, and costly. Requires expertise in cell culture and micromanipulation [3] [14]. | Relatively simple, faster, and more efficient protocol. Easier to integrate into standard embryo transfer workflows [3]. |

| Germline Transmission | The edited genotype is guaranteed to be in all cells, including germlines, and is transmitted to offspring [14]. | Mosaic founders may not carry the edit in their germlines, preventing inheritance and requiring additional breeding [3]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Essential for complex, multiplexed edits where genotype must be 100% confirmed before animal generation (e.g., xenotransplantation pigs) [14]. | Preferred for high-throughput applications and breeding programs where simplicity and speed are prioritized, and mosaicism can be managed [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

Q1: Why is mosaicism such a significant problem in livestock research? Mosaicism is problematic because it can lead to an inconsistent presentation of the desired trait and, critically, the edited genotype may be absent from the animal's germline (sperm or egg cells) [3]. This prevents the founder animal from passing the modification to its offspring. Given the long generation intervals and high rearing costs of livestock, failing to secure germline transmission represents a major setback in a breeding program [3].

Q2: If SCNT avoids mosaicism, why isn't it the default method? While SCNT produces non-mosaic animals, it is a technically demanding, inefficient, and costly process [3] [14]. In contrast, direct zygote editing is a simpler, more accessible procedure that can be more readily adopted by laboratories and integrated into existing livestock embryo transfer programs, making it appealing despite the mosaicism challenge [3].

Technical & Troubleshooting

Q3: What are the key factors I can adjust in my experiment to reduce mosaicism? You can optimize your protocol by focusing on four key areas [3]:

- CRISPR-Cas9 Format: Using Cas9 protein in a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex can lead to faster activity and degradation, reducing persistent editing.

- Delivery Method & Timing: Electroporation of RNP complexes into zygotes can provide more synchronized delivery than microinjection. The timing of delivery relative to fertilization is critical to ensure editing occurs before the first DNA replication.

- Type of Genome Editor: Newer editors like base editors or prime editors, which do not cause double-strand breaks, may offer advantages.

- Use of Enhancers: Co-delivering small molecules or other enzymes can improve the efficiency and timing of editing.

Q4: Are there specific reagents that can help suppress mosaic mutations? Yes, research shows that co-delivering exonucleases like murine Trex2 (mTrex2) with CRISPR-Cas9 can significantly increase the rate of non-mosaic embryos. In one porcine study, the rate of non-mosaic blastocysts increased from 5.6% with CRISPR-Cas9 alone to 29.3% when mTrex2 mRNA was co-delivered [15]. It is hypothesized that Trex2 processes DNA ends to improve the efficiency of mutation induction at the one-cell stage [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating Mosaicism

This section provides a structured workflow to diagnose and address the causes of high mosaicism in your experiments. The following diagram outlines the key decision points and optimization strategies.

Diagram 1: A troubleshooting workflow for identifying and correcting common causes of mosaicism in direct zygote editing experiments.

Problem: Inefficient Editing in the One-Cell Stage

Potential Cause: The CRISPR-Cas9 system remains active too long or editing is not completed before the first embryonic cleavage, causing edits to occur in multiple cell lineages over time [3] [15].

Solutions:

- Use Cas9 RNP Complexes: Deliver pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and sgRNA. RNPs are active immediately upon delivery and degrade quickly, limiting the window of editing activity and reducing persistent cuts in subsequent cell divisions [3] [15].

- Optimize Delivery Timing: Introduce CRISPR reagents as early as possible in the one-cell stage, ideally during the S-phase of the cell cycle, to maximize the chance that edits are incorporated before DNA replication [3] [16].

- Modify Environmental Conditions: In zebrafish, reducing the incubation temperature of injected zygotes from 28°C to 12°C extended the single-cell stage and was associated with increased mutagenesis efficiency, providing more time for editing to occur [17]. While specific to fish, this demonstrates the principle that controlling the cell cycle can improve results.

Problem: Low Efficiency of Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Potential Cause: The error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway dominates DNA repair in zygotes, leading to a high frequency of indels. If an NHEJ event disrupts the gRNA target site before HDR can occur, the opportunity for precise editing is lost [3].

Solutions:

- Employ HDR Enhancers: Co-deliver small molecules that inhibit NHEJ or stimulate the HDR pathway. For example, RS-1, which stimulates the HDR protein Rad51, has been investigated for this purpose [3].

- Utilize Advanced Editors: For specific point mutations, use base editors or prime editors. These systems do not create double-strand breaks and can achieve precise changes without relying on the HDR pathway, thereby avoiding competing repair mechanisms [14] [18].

- Co-deliver Exonucleases: As demonstrated in FAQ 4, the exonuclease mTrex2 can be co-delivered to enhance mutation efficiency at the one-cell stage, increasing the proportion of non-mosaic embryos [15].

Featured Experimental Protocol: Suppressing Mosaicism with Trex2

This protocol details the methodology from a key study that successfully reduced mosaicism in porcine embryos by co-delivering CRISPR-Cas9 and mTrex2 via electroporation [15].

Objective: To generate non-mosaic mutant porcine embryos by improving editing efficiency at the one-cell stage. Key Reagents: The essential materials and their functions are listed below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for the Trex2 Co-delivery Protocol

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein | The endonuclease that creates a double-strand break at the target DNA sequence. Using protein (RNP) allows for rapid activity. |

| sgRNA | Single-guide RNA that directs the Cas9 protein to the specific genomic target site. |

| mTrex2 mRNA | mRNA encoding murine three-prime repair exonuclease 2. Co-delivered to enhance mutation induction by processing DNA ends [15]. |

| Porcine Zygotes | In vitro matured (IVM) and fertilized (IVF) one-cell stage embryos. |

| Electroporator | Device for delivering electrical pulses to introduce macromolecules into cells (e.g., using the TAKE or GEEP method) [15]. |

| Opti-MEM Medium | A reduced-serum medium used for handling and diluting nucleic acids and proteins during electroporation. |

Methodology:

- Preparation of Reagents: In vitro transcribe and purify mTrex2 mRNA and the target-specific sgRNA [15].

- Complex Formation: Pre-assemble the Cas9 protein with the sgRNA to form RNP complexes.

- Electroporation: Mix the RNP complexes with mTrex2 mRNA in Opti-MEM medium. Introduce the mixture into porcine zygotes using an electroporator with optimized parameters [15].

- Embryo Culture: After electroporation, wash the zygotes and culture them in a suitable embryo culture medium until they reach the blastocyst stage (typically 5-7 days).

- Genotype Analysis: Harvest individual blastocysts and use a method like Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) or next-generation sequencing to analyze the editing efficiency and determine the percentage of non-mosaic, mosaic, and wild-type embryos [15].

Expected Outcome: The study demonstrated a significant increase in the proportion of non-mosaic mutant blastocysts (from 5.6% to 29.3%) and a corresponding decrease in mosaic blastocysts (from 92.6% to 70.7%) with the co-delivery of mTrex2, without affecting pre-implantation development rates [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "heritability problem" in the context of CRISPR-edited organisms? The "heritability problem" refers to the challenge of ensuring that a genetically edited trait is stably and uniformly passed from a founder organism (F0) to its offspring (F1 and beyond). A primary obstacle is genetic mosaicism, where the founder organism develops with more than two different alleles of the edited gene in its different cells [9] [3]. This happens because the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery remains active and can edit DNA over several cell divisions after the initial zygote injection. Consequently, an edited founder may not carry the intended edit in its germline cells (sperm or eggs), meaning the edit cannot be inherited by the next generation [19].

Q2: How does mosaicism impact the establishment of a pure breeding founder line? Mosaicism significantly complicates and prolongs the establishment of a stable, homozygous breeding line. Key impacts include [9] [19] [3]:

- Unpredictable Germline Transmission: A mosaic founder must be bred to wild-type partners to determine if, and which, edited alleles are present in its gametes.

- Extended Timelines: Multiple breeding cycles (to the F2 generation or beyond) are often required to identify and isolate a single desired edit from the multiple alleles present in a mosaic founder.

- Resource Intensiveness: Breeding and genotyping numerous offspring is costly and time-consuming, especially in species with long generation intervals like livestock.

Q3: What are the primary technical causes of mosaicism? Mosaicism arises when gene editing continues after the first embryonic cell division. The main factors influencing this are [9] [3]:

- Timing of Editing Activity: If CRISPR components are delivered too late, the embryo may have already divided, and editing occurs in only some cells.

- Persistence of CRISPR Components: The Cas9 protein and guide RNA can remain active in the embryo for multiple cell cycles, causing sequential, non-simultaneous edits in daughter cells.

- Delivery Method and Format: The method (e.g., microinjection, electroporation) and the format of the CRISPR machinery (e.g., mRNA, protein) can affect how quickly and uniformly editing occurs.

Q4: Can mosaicism ever be beneficial for research? Yes, in some specific cases, mosaicism can be a powerful tool. It can be used to model diseases where a homozygous mutation is lethal, allowing researchers to study the function of a gene by comparing mutant and wild-type cells within the same animal. For example, CRISPR-engineered mosaicism was used to rapidly validate that loss of Kcnj13 function in mice mimics human blindness phenotypes, overcoming the postnatal lethality of homozygous null alleles [19].

Q5: What is the risk of accidental germline transmission in human clinical trials? For in vivo CRISPR therapies (where editing components are infused directly into a patient), the risk of unintentionally editing a patient's sperm or egg cells is a critical safety concern. Recent data from clinical trials is reassuring. Intellia Therapeutics reported studies in non-human primates showing "that there’s no evidence of vertical germline transmission of those edits" from their CRISPR-based therapy for transthyretin amyloidosis [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Overcoming Low Germline Transmission Rates

Problem: A founder (F0) animal confirmed to carry a desired edit via tissue biopsy fails to transmit the edit to its progeny.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Germline Mosaicism. The edit is present in the founder's somatic cells (e.g., skin) but not in its germline cells [19].

- Solution: Breed the founder extensively. Genotype a large number of offspring to determine if the edit is present at low frequency in the germline. If no transmission is observed, the founder is not suitable for establishing a line.

- Cause: Chimerism vs. Mosaicism. The founder may be a chimera (composed of cells from different zygotes) rather than a mosaic from a single edited zygote.

- Solution: Perform deep sequencing analysis on DNA from multiple tissues (including germline tissues if possible) to confirm the origin and distribution of edits [3].

- Preventative Strategy: Use early microinjection or RNP delivery to maximize the chance of the edit occurring in cells that will contribute to the germline [9].

Guide 2: Strategies to Minimize Mosaicism in Founder Generation

The core strategy is to ensure editing occurs completely and uniformly before the first cell division. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from studies that successfully reduced mosaicism.

Table 1: Experimental Strategies to Reduce Mosaicism

| Strategy | Protocol Description | Key Finding | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Zygote Microinjection [9] | Microinjection of CRISPR mRNA/sgRNA at 10 hours post-insemination (hpi) in bovine embryos, instead of the conventional 20 hpi. | DNA replication begins early; ~40% of zygotes were already in S-phase at 10 hpi. | Mosaicism reduced from 100% (20 hpi) to ~30%, with no loss of editing efficiency. |

| Oocyte Microinjection (RNA) [9] | Microinjection of CRISPR mRNA/sgRNA into bovine oocytes before fertilization (0 hpi), followed by IVF. | Enables presence of CRISPR machinery at the earliest possible stage (fertilization). | Mosaicism rate of ~10%, with high genome edition rates (>80%). |

| Oocyte Microinjection (RNP) [9] | Microinjection of pre-complexed Cas9 protein and sgRNA (ribonucleoprotein, RNP) into oocytes before fertilization. | RNP acts faster than mRNA, which must be translated first, leading to more rapid and transient activity. | Mosaicism rate of ~30%, with high genome edition rates (>80%). |

| Use of High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants [4] | Employing engineered Cas9 versions (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) with reduced off-target activity. | Improved specificity can reduce unpredictable cleavage and complex mutation patterns that contribute to mosaicism. | Improved specificity leads to cleaner genotyping and more predictable editing patterns, indirectly aiding mosaic analysis. |

Guide 3: Experimental Protocols for Reducing Mosaicism

Protocol: Early Microinjection of CRISPR RNP in Bovine Zygotes [9]

Objective: To achieve high editing efficiency while minimizing genetic mosaicism in bovine embryos.

Materials:

- In vitro matured bovine oocytes

- CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (pre-assembled from purified Cas9 protein and synthetic sgRNA)

- Microinjection system (e.g., piezo-driven micromanipulator)

- Culture media for embryo development

Workflow:

- Oocyte Preparation: Collect metaphase II (MII) oocytes and remove cumulus cells.

- RNP Complex Preparation: Complex the sgRNA with Cas9 protein according to manufacturer's instructions and keep on ice.

- Microinjection: Using a piezo-driven microinjection needle, deliver a precise volume of the RNP complex directly into the cytoplasm of the oocyte.

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Immediately after microinjection, fertilize the oocytes using standard IVF procedures.

- Embryo Culture: Culture the resulting zygotes under standard conditions to the blastocyst stage.

- Genotyping: Analyze blastocysts using PCR, followed by deep sequencing (e.g., clonal sequencing of 10+ colonies per embryo) to accurately determine the number and type of alleles present.

Rationale: Delivering pre-formed RNP complexes at the oocyte stage ensures the genome editing machinery is active immediately upon fertilization. The transient nature of RNP activity (as the protein degrades naturally) limits the window for editing, reducing the chance of sequential edits in daughter cells and thus lowering mosaicism [9].

Diagram: RNP microinjection workflow for reducing mosaicism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Addressing Mosaicism and Heritability

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) [9] | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and guide RNA. Delivered directly into the oocyte or zygote. | Faster editing kinetics and reduced persistence compared to mRNA delivery, leading to lower mosaicism. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants [4] | Engineered Cas9 proteins with mutated amino acids to reduce off-target binding. | Minimizes unintended cuts, simplifying the genotyping profile and reducing the risk of complex, mosaic-inducing mutations. |

| Chemical Enhancers (e.g., RS-1) [3] | Small molecules that modulate DNA repair pathways. | Can be added to culture media to promote Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) over error-prone NHEJ, favoring precise edits. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [3] | Deep sequencing of PCR amplicons from edited embryos or tissues. | Essential for accurate diagnosis of mosaicism. Distinguishes between multiple alleles in a sample, which Sanger sequencing cannot reliably do. |

| Locus-Specific Genotyping Assays [21] | PCR-based detection kits (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I, Surveyor Assay) for initial cleavage screening. | Useful for a quick, low-cost assessment of editing efficiency but lacks the sensitivity to detect low-level mosaicism or multiple alleles. |

Diagram: Logical relationship between mosaicism causes and mitigation strategies.

Strategic Interventions: Editor Selection, Delivery, and Timing to Reduce Mosaicism

Mosaicism, the occurrence of multiple genetically distinct cell populations within a single organism, is a significant challenge in CRISPR-edited research models. It complicates phenotypic analysis, reduces experimental reproducibility, and can hinder the generation of stable animal lines. The choice of genome-editing tool—conventional Cas9, base editors, or prime editors—profoundly influences the frequency and extent of mosaicism. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help researchers select the appropriate editor and design strategies to minimize mosaicism in their experiments.

FAQ: Mosaicism in CRISPR Editing

What causes mosaicism in CRISPR-edited organisms?

Mosaicism primarily occurs when genome editing takes place after the zygote has already begun DNA replication and cell division. If the CRISPR machinery, such as Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA, remains active through several cell cycles, it can edit different cells at different times or in different ways, leading to a mixture of edited and unedited cells within a single organism [22]. This is a common limitation when using CRISPR/Cas9 directly in embryos, as it is impossible to select for the desired editing event at the single-cell stage [22].

Why is mosaicism a problem for research and therapy?

Mosaicism presents several critical challenges:

- Phenotype Interpretation: The presence of a mix of edited and unedited cells can mask or dilute the true phenotypic effect of a genetic modification, leading to inaccurate conclusions [22].

- Validation Complexity: Founder animals (G0) exhibiting mosaicism require extensive and costly genomic validation to identify and segregate the desired edit through breeding, as their germline may not uniformly carry the mutation [22].

- Therapeutic Uncertainty: In therapeutic contexts, mosaicism means the genetic correction is not uniform across all target cells, which can severely limit the treatment's efficacy and predictability [23].

How does the DNA repair mechanism influence mosaicism?

The editor's mechanism dictates the cellular repair pathway involved, which in turn affects the consistency of editing outcomes across cells.

- Conventional Cas9 relies on the creation of double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are repaired by often error-prone pathways like non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or, less frequently in non-dividing cells, microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) [24] [23]. The competition between these pathways and the potential for repeated cutting and repair of the same locus can lead to a diverse array of indels, fueling mosaicism [22].

- Base Editors and Prime Editors do not create DSBs. Instead, they directly alter a single DNA base or use a reverse transcriptase template to "write" new genetic information, respectively [24]. By avoiding the complex and variable DSB repair process, these editors generally produce more uniform outcomes and lower mosaicism frequencies.

Quantitative Comparison of Editors and Mosaicism

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each editor type relevant to mosaicism.

| Feature | Conventional Cas9 | Base Editors | Prime Editors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Mechanism | Creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) [24] | Chemical conversion of single bases without a DSB [24] | Reverse transcription of edited sequence from a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) without a DSB [24] |

| Primary Repair Pathway | NHEJ, MMEJ, HDR [24] [23] | DNA mismatch repair [24] | DNA repair machinery (not fully characterized) [24] |

| Relative Mosaicism Frequency | High [22] | Lower [25] | Lower (theoretical, due to no DSB) [24] |

| Key Advantage for Reducing Mosaicism | N/A | Avoids DSB repair variability; faster, more uniform editing [25] [23] | Avoids DSB repair variability; highly precise edits [24] |

| Key Limitation | Unpredictable repair outcomes; repeated cutting promotes mosaicism [22] | Restricted to specific base transitions; requires a precise window for editing [24] | Lower efficiency in some systems; complex pegRNA design [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing and Reducing Mosaicism

Protocol 1: Validating Editing and Detecting Mosaicism in Founder Models

This protocol outlines a robust method for confirming edits and quantifying mosaicism in founder (G0) generation organisms, a critical step given that "founder mice generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 approach [are often] mosaic" [22].

- Sample Collection: Collect tissue samples (e.g., ear clip, tail tip) from founder animals. For a comprehensive assessment, consider analyzing multiple tissues.

- DNA Extraction: Ispose high-quality genomic DNA from the collected tissues.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers flanking the target edited region and perform PCR amplification.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Prepare amplicon sequencing libraries from the PCR products and sequence to high coverage. This method is superior to traditional sequencing as it reveals the diversity of editing outcomes within a single sample [22].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use computational tools (e.g., CRISPResso2) to analyze the NGS data. This will quantify the:

- Overall editing efficiency (percentage of reads with any edit).

- Spectrum of alleles (types and frequencies of different indels or base changes).

- Degree of mosaicism, indicated by the presence of three or more distinct allele sequences in a single sample.

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Selecting Editors to Minimize Mosaicism

The following diagram outlines a decision-making process for choosing a CRISPR editor based on research goals and mosaicism concerns.

Editor Selection Workflow

Strategic Considerations for Each Editor

- Conventional Cas9 (for Knockouts): Acknowledge the high risk of mosaicism and allele complexity [22]. Plan for extensive breeding and genotyping of the G1 offspring to establish a stable, non-mosaic line. Using Cas9 in a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex, rather than as mRNA, can shorten its activity window and may reduce mosaicism.

- Base Editors (for Point Mutations): These are excellent for installing precise point mutations (e.g., C•G to T•A or A•T to G•C) without inducing DSBs. A recent study in a sickle cell disease model demonstrated that base editing outperformed CRISPR-Cas9 in reducing red cell sickling, with higher editing efficiency and fewer genotoxicity concerns, underscoring its potential for cleaner outcomes [25].

- Prime Editors (for Small Edits): As the most precise tool that avoids DSBs, prime editors are ideal for small insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible base-to-base conversions. While in vivo efficiency can be a challenge, their mechanism inherently reduces the likelihood of the heterogeneous outcomes that cause mosaicism [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

The table below lists key reagents used in advanced CRISPR editing workflows, particularly those featured in studies aiming for high-precision, low-mosaicism outcomes.

| Research Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) [23] | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and guide RNA. Direct delivery of RNP into cells (e.g., via electroporation) leads to rapid editing and degradation, shortening the editing window and potentially reducing mosaicism compared to mRNA delivery. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) [23] | Engineered particles that deliver Cas9 protein (as RNP) instead of genetic material. Used for transient, efficient delivery to hard-to-transfect cells like neurons, minimizing persistent nuclease activity. |

| Prime Editing Guide RNA (pegRNA) [24] | A specialized guide RNA that both targets the editor to a specific locus and encodes the desired edit. It is the central component of the prime editing system, enabling precise, DSB-free modifications. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [26] | A delivery vehicle for in vivo CRISPR therapy. LNPs can encapsulate and deliver mRNA encoding editors or the editors themselves (as RNP), and their transient nature is favorable for reducing mosaicism. They also allow for potential re-dosing [26]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits [22] | Essential for the deep sequencing of amplicons from founder animals. This is the gold-standard method for quantifying editing efficiency and characterizing the spectrum of alleles to detect and measure mosaicism. |

In CRISPR-edited organisms, a significant challenge facing researchers is mosaicism—the presence of both edited and unedited cells within the same organism. This phenomenon directly complicates phenotypic analysis and the generation of reliable animal models, as the genetic makeup is not uniform across all cells. The root of this problem is often traced back to the timing and efficiency of the CRISPR-Cas9 delivery method. When the CRISPR system is delivered after the one-cell stage, the editing machinery may not be present in all daughter cells, or the DNA double-strand break may occur after initial cell divisions have already begun. Consequently, selecting a delivery strategy that ensures the CRISPR components are present and active at the earliest possible stage is paramount to generating homogeneous, non-mosaic edited organisms. The following guide addresses this core issue by dissecting the most common delivery methods, their associated challenges, and proven troubleshooting strategies.

FAQ: Navigating Common Delivery Challenges

Q1: My editing efficiency is low. How can I improve it? Low editing efficiency can stem from multiple factors. First, verify your guide RNA (gRNA) design; ensure it targets a unique genomic sequence and has high predicted on-target activity, which can be evaluated using online tools and machine-learning models [4] [27]. Second, optimize your delivery method and conditions. Different cell types may require different delivery strategies, such as electroporation, lipofection, or viral vectors [4]. Finally, confirm the expression levels of Cas9 and the gRNA. Using a promoter that is highly active in your specific cell type and ensuring the quality and concentration of your plasmid DNA, mRNA, or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) are crucial [4].

Q2: How can I minimize off-target effects in my experiments? Off-target effects, where Cas9 cuts at unintended sites, are a major concern. To minimize them:

- Design highly specific gRNAs: Utilize bioinformatics tools that predict potential off-target sites across the genome to select a gRNA with minimal off-target risks [4] [27].

- Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants: Engineered Cas9 proteins with improved specificity are available and can significantly reduce off-target cleavage [4].

- Choose a transient delivery format: Delivering CRISPR-Cas9 as a preassembled RNP complex leads to rapid degradation and a shorter cellular presence, which reduces the window for off-target activity compared to long-lasting plasmid DNA (pDNA) [28] [29].

- Employ inducible systems: For plasmid-based delivery, a tetracycline-inducible system can control the timing of Cas9 expression, minimizing persistent exposure [29].

Q3: I suspect mosaicism in my model. What can I do to reduce it? Mosaicism occurs when editing happens after the zygote has begun to divide. To address this:

- Optimize the timing of delivery: Ensure the CRISPR components are delivered at the earliest possible stage. For microinjection in embryos, inject into the cytoplasm or pronuclei of fertilized eggs [4].

- Use delivery formats with rapid activity: The RNP format acts most quickly because it bypasses the need for transcription and translation, leading to faster genome editing and potentially reducing mosaicism [28] [29].

- Employ single-cell cloning: After editing a population of cells, you can isolate and expand single cells to derive fully edited clonal cell lines, effectively eliminating mosaicism in your sample [4].

Q4: My cells are showing toxicity after CRISPR delivery. What might be the cause? Cell toxicity can be caused by high concentrations of the CRISPR components or the delivery method itself.

- Titrate your CRISPR components: Start with lower doses of pDNA, mRNA, or RNP and gradually increase to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [4].

- Consider the delivery vehicle: Electroporation can be damaging to sensitive cells. For these, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or viral vectors may be a gentler alternative [29] [30].

- Switch cargo format: The delivery of plasmid DNA can sometimes trigger stronger cellular immune responses compared to mRNA or RNP formats [29].

Delivery Method Deep Dive: Strategies and Protocols

The choice of how to deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 system—as plasmid DNA (pDNA), messenger RNA (mRNA), or a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex—profoundly impacts the kinetics, specificity, and ultimate success of your genome editing experiment. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each cargo format.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Cargo Formats

| Cargo Format | Mechanism of Action | Time to Activity | Risk of Off-Target Effects | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | Requires nuclear import, transcription, and translation [28]. | Slowest (24-48 hours) [28]. | Highest, due to persistent expression [28] [29]. | Simple, cost-effective, and stable; easy to scale up [31] [29]. | Risk of insertional mutagenesis; high immunogenicity; prolonged expression increases off-target risk [28] [29]. |

| mRNA | Requires only translation in the cytoplasm [28]. | Intermediate (faster than pDNA) [29]. | Moderate; transient expression reduces off-target risk [29]. | No risk of genomic integration; quicker activity than pDNA [29]. | mRNA is unstable and susceptible to degradation; production is more complex than for pDNA [28] [29]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-assembled complex is immediately active upon nuclear entry [28]. | Fastest (editing detected from 1 hour) [28]. | Lowest; short-lived activity minimizes off-target effects [28] [32]. | Highest efficiency; no risk of integration; immediate activity reduces mosaicism [29] [32]. | Protein production is labor-intensive and expensive; complexes are less stable [28] [29]. |

Physical Delivery Methods

Physical methods force the CRISPR cargo directly into cells by temporarily disrupting the cell membrane.

Table 2: Physical Delivery Methods for CRISPR-Cas9

| Method | Principle | Ideal Cargo | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microinjection | Fine needle used to inject cargo directly into the cytoplasm or nucleus [29]. | pDNA, mRNA, RNP [29]. | Single cells, such as zygotes and embryos [33] [29]. | High precision and efficiency at the single-cell level [29]. | Technically demanding, low throughput, and can be damaging to cells [29]. |

| Electroporation | Short electrical pulses create temporary pores in the cell membrane [29]. | pDNA, mRNA, RNP [29] [32]. | In vitro cells and ex vivo editing of patient cells (e.g., T-cells) [33] [29]. | Highly efficient for a broad range of cell types [29]. | Can cause significant cell death if not optimized [29]. |

Experimental Protocol: Electroporation of RNP Complexes This protocol is adapted from methods used for editing human keratinocytes and T-cells [32].

- Complex Formation: Pre-assemble the RNP complex by mixing purified Cas9 protein with synthetic gRNA at a specified molar ratio (e.g., a 6.6:1 sgRNA:Cas9 ratio) in a nuclease-free buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow the complex to form.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest the target cells and resuspend them in an electroporation-compatible buffer at a recommended concentration (e.g., 1-10 x 10^6 cells/mL).

- Electroporation: Mix the cell suspension with the pre-assembled RNP complexes. Transfer the mixture to an electroporation cuvette. Apply the optimized electrical pulse specific to your cell type (e.g., for human RDEB keratinocytes, specific conditions would need to be determined empirically).

- Recovery: Immediately after electroporation, transfer the cells to pre-warmed culture medium and incubate at 37°C. Analyze editing efficiency after 48-72 hours using methods like T7 endonuclease I assay or sequencing.

Viral vs. Non-Viral Delivery Strategies

For in vivo delivery or hard-to-transfect cells, vector-based systems are often required.

Table 3: Viral vs. Non-Viral Delivery Vectors

| Delivery Vector | Cargo Capacity | Integration into Genome | Immunogenicity | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Very limited (~4.7 kb) [33] [30]. | No [30]. | Low [33] [30]. | In vivo delivery [29]. |

| Lentivirus (LV) | High (~8 kb) [30]. | Yes [29] [30]. | Moderate [29]. | In vitro and ex vivo delivery; large-scale screens [29]. |

| Adenovirus (AdV) | Very high (~36 kb) [30]. | No [30]. | High [29]. | In vivo delivery where large cargo is needed [30]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Varies, but generally high. | No [29]. | Low to moderate [30]. | In vivo mRNA/RNP delivery and clinical therapies [29] [30]. |

| Polymer-Based Nanoparticles | Varies, but generally high. | No [33] [32]. | Low [33]. | In vitro and in vivo delivery of various cargo types [33] [32]. |

Visualizing the Workflow: From Delivery to Mosaic Outcome

The diagram below illustrates the critical juncture at which the choice of delivery method and its timing influences the development of mosaic versus non-mosaic organisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Delivery

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Nuclease | Engineered to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target efficiency. | SpCas9-HF1 [4]; Important for therapeutic applications and sensitive models. |

| Cationic Polymer Transfection Reagent | Condenses nucleic acids into nanoparticles for cell delivery via endocytosis. | Highly Branched Poly(Beta-Amino Ester) (HPAE-EB) [32]; Effective for delivering both DNA and RNP complexes. |

| Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic particles that encapsulate and protect CRISPR cargo for in vivo delivery. | Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) LNPs [30]; Can be engineered to target specific tissues like lung, spleen, and liver. |

| Pre-complexed RNP Kits | Ready-to-use, pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA complexes for maximum editing efficiency and minimal off-targets. | Commercial kits are available; Ideal for electroporation and hard-to-transfect cells. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmids | DNA vectors for expression of Cas9 and gRNA within the target cell. | pX330, pX459 [31] [33]; Often use a U6 promoter for gRNA and a CAG or CBh promoter for Cas9. |

FAQs: Understanding Timing and Mosaicism in Zygote Editing

Q1: Why does initiating CRISPR editing in the single-cell zygote stage reduce mosaicism?

Mosaicism occurs when edited and unedited cells coexist in the same organism. This typically happens if the CRISPR-Cas9 system components are active over multiple cell divisions after the first zygotic division. When editing is achieved in the single-cell zygote, the Cas9-induced double-strand break and repair occur before the first cell division. This means the genetic edit is present in the entire initial cell mass and is therefore propagated to all subsequent daughter cells, resulting in a non-mosaic organism [4].

Q2: What are the key timing-related factors to consider for zygote editing?

The primary goal is to ensure the CRISPR machinery completes the editing before the zygote divides. Key factors include:

- Time of Injection: Microinjection of CRISPR reagents into the zygote should be performed as early as possible, typically at the pronuclear stage.

- Component Format: Using Cas9 protein complexed with guide RNA as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) leads to faster editing action compared to mRNA, which must first be translated into protein. RNP delivery initiates editing immediately, while mRNA-based editing requires waiting for Cas9 protein expression [34] [35].

- Cell Cycle Stage: The efficiency of different DNA repair pathways (NHEJ vs. HDR) varies with the cell cycle stage. Synchronizing delivery with the optimal stage for the desired repair outcome is crucial [4].

Q3: Our lab achieves high editing rates in zygotes but still observes mosaicism. What are we missing?

Even with zygote injection, mosaicism can persist if the editing process is not complete before the first division. To minimize this:

- Switch to RNP Delivery: If you are using plasmid DNA or mRNA, switching to pre-complexed RNP can significantly accelerate the cutting kinetics [34].

- Optimize Concentration: Titrate the concentration of your RNP or mRNA/sgRNA to find the optimal balance between high editing efficiency and minimal toxicity. Too low a concentration may result in delayed or incomplete editing [4] [35].

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9: Standard Cas9 can have prolonged activity, increasing the chance of cuts in subsequent cell divisions. High-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9) can reduce this window of activity, limiting off-target effects and potential mosaicism [4] [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Zygote Editing Challenges

Problem: Low Survival Rate of Injected Zygotes

| Potential Cause | Solution | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity from high CRISPR component concentration | Titrate the concentration of Cas9 RNP or mRNA/sgRNA. Start low and increase until editing is observed. | High concentrations of Cas9 and gRNA can trigger p53-mediated cell death pathways [4] [36]. |

| Technical damage during microinjection | Practice and optimize injection technique. Use piezoelectric-driven injectors to reduce mechanical damage. | Ensure sharp, clean injection needles and control the injection volume precisely. |

| Toxic contaminants in reagents | Use highly purified, endotoxin-free Cas9 protein and synthetic sgRNAs. | Verify the quality and concentration of plasmid DNA or mRNA if used, as impurities can impact viability [4]. |

Problem: High Mosaicism Despite Zygote Injection

| Potential Cause | Solution | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Delayed onset of Cas9 activity | Switch from mRNA to Cas9 RNP for immediate activity. | RNP delivery leads to faster editing and reduced mosaicism as the complex is active immediately upon delivery [34]. |

| Prolonged Cas9 expression | Use a transient delivery method (RNP) instead of DNA vectors. | If using plasmids, the continuous expression of Cas9 can lead to editing in multiple cell cycles [34]. |

| Suboptimal gRNA design | Redesign gRNAs using algorithmic tools to maximize on-target efficiency. Test multiple gRNAs. | A highly efficient gRNA will create a double-strand break more rapidly, increasing the chance of completion before the first division [4] [37]. |

| Potential Cause | Solution | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient gRNA | Utilize online design tools to predict and select high-efficiency gRNAs. Test 3-4 gRNAs per target [35]. | gRNA efficiency is influenced by its sequence and the local chromatin accessibility of the target site [36]. |

| Inefficient delivery into the nucleus | Use Cas9 with a nuclear localization signal (NLS). For RNP, ensure the complex is properly formed. | The CRISPR components must reach the nucleus to access the genomic DNA. A nuclear localization signal is essential for this [4]. |

| Target site inaccessible | Check if the target region is in heterochromatin. Consider using cell cycle synchronization strategies. | Tightly packed DNA (heterochromatin) is harder for CRISPR machinery to access, reducing editing efficiency [36]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimized Workflow for Murine Zygote Editing

This protocol is adapted from a strategy for complex gene targeting in murine embryonic stem cells for germline transmission, optimized for direct zygote injection to minimize mosaicism [37].

Objective: To achieve high-efficiency, non-mosaic editing through microinjection of CRISPR reagents into single-cell murine zygotes.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

| Reagent / Material | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease (with NLS) | RNA-guided endonuclease that creates a double-strand break in the target DNA. | Using high-fidelity Cas9 (e.g., eSpCas9) can reduce off-target effects and the window of activity, potentially lowering mosaicism [4] [34]. |

| synthetic sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 protein to the specific genomic target sequence. | Highly purified, synthetic sgRNA is recommended over in vitro transcription to reduce toxicity and improve reproducibility [34]. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Template | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or double-stranded DNA vector for precise knock-in. | Must be co-injected with Cas9 RNP and designed with homology arms flanking the desired edit [34] [37]. |

| Microinjection Apparatus | For delivering reagents directly into the pronucleus or cytoplasm of the zygote. | Includes a micromanipulator, injector, and microscope. |

| Murine Zygotes | Fertilized single-cell embryos for injection. | Collected from superovulated female mice. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Preparation of CRISPR Reagents:

- Complex the purified Cas9 protein with synthetic sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:3 to 1:5 (Cas9:gRNA) to form the RNP. Incubate at 37°C for 10-15 minutes to allow complex formation.

- If performing HDR, dilute the ssODN HDR template in the injection buffer. A typical final concentration for the RNP mixture is 50 ng/µL Cas9 with 20 ng/µL sgRNA.

Zygote Collection and Handling:

- Collect zygotes from superovulated female mice at the pronuclear stage (0.5 days post-coitum).

- Prepare holding and injection pipettes on the microinjection setup.

Microinjection:

- Load the pre-complexed RNP mixture (with or without HDR template) into the injection needle.

- Carefully inject the mixture into the larger pronucleus of the zygote. Limit the injection volume to minimize damage to the embryo.

Post-Injection Culture and Transfer:

- After injection, wash and culture the zygotes in embryo culture medium overnight.

- The following day, assess the development to the 2-cell stage. This is a key indicator of embryo health after the invasive procedure.

- Transfer viable 2-cell embryos into the oviducts of pseudo-pregnant foster female mice.

Genotyping and Analysis:

- After birth, genotype the founder (F0) animals using a robust method, such as PCR followed by sequencing, to assess the editing efficiency and screen for mosaicism.

- Compare the sequencing chromatograms from tail-clip DNA. A clean, single sequence peak indicates a non-mosaic edit, while overlapping peaks at the target site suggest mosaicism.

Visualizing the Strategy: From Zygote to Non-Mosaic Organism

The diagram below illustrates the critical difference in outcomes when CRISPR editing is completed before versus after the first cell division.

A significant obstacle in CRISPR-mediated genome editing, particularly in single-cell embryos, is the high incidence of genetic mosaicism. This phenomenon occurs when an edited organism possesses a mixture of cells with different genetic genotypes. In the context of CRISPR, it arises when DNA replication precedes the completion of genome editing, leading to an organism with both edited and unedited cells [38]. This is undesirable as it reduces the odds of generating direct knockout (KO) models and complicates phenotypic analysis.

This technical support article explores how the delivery of pre-assembled CRISPR Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes serves as a powerful strategy to mitigate mosaicism and accelerate genome editing workflows. RNP delivery involves the direct introduction of the purified Cas9 protein complexed with its guide RNA into cells, offering a transient yet highly active editing system that acts before the first cell division in embryos [38] [39].

Why RNP Complexes? Core Advantages for Efficient Editing

RNP delivery presents several distinct advantages over DNA-based methods (such as plasmids) or mRNA delivery, which directly address the causes of mosaicism and improve experimental efficiency.

- Rapid Onset of Editing Activity: Since the Cas nuclease is already complexed with its guide RNA, no transcription or translation is required inside the cell. The RNP complex is active immediately upon entering the nucleus, leading to faster editing [40] [41]. This rapid activity is crucial for editing the zygote before DNA replication and cell division, thereby reducing mosaicism [38].

- Reduced Off-Target Effects and Cellular Toxicity: The transient nature of RNP complexes means the Cas9 protein is degraded quickly by natural cellular processes, minimizing the time window for off-target cleavage events [39] [40] [41]. Delivery of CRISPR components as DNA plasmids or mRNA leads to prolonged Cas9 expression, increasing the risk of off-target effects and potential cytotoxicity [42] [39].

- High Editing Efficiency in Challenging Cell Types: RNP delivery has proven highly effective in cell types that are notoriously difficult to transfect, including primary cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [42] [40] [41].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of RNP vs. Plasmid Delivery in Selected Studies

| Cell Type/Organism | Editing Construct | Key Performance Metric | Result with RNP | Result with Plasmid | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary CD34+ cells & Leukemia cells | CRISPR/Cas9 | Cell Viability | Higher cell viability post-electroporation | Lower cell viability | [42] |

| Bovine Zygotes | CRISPR/Cas9 | Mosaicism Rate | ~10-30% of edited embryos were mosaic | 100% mosaicism (conventional injection) | [38] |

| General Mammalian Cells | CRISPR/Cas9 | Time to Maximal Mutation Frequency | ~24 hours | Delayed (requires transcription/translation) | [41] |

Visual Workflow: RNP Complex Assembly and Action

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structure of an RNP complex and its mechanism for creating a double-strand break in DNA.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: RNP Delivery via Electroporation

This protocol is adapted from studies on primary hematopoietic cells and can be optimized for other sensitive cell types [42].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RNP Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Source / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | The CRISPR nuclease component. High-purity, commercial grade recommended. | e.g., PNA Bio [42] |

| Guide RNA (synthesized) | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic locus. Can be chemically synthesized with modifications to enhance stability. | e.g., Alt-R modified gRNAs [39] |

| Electroporation System | Physical method for delivering RNP into cells. | e.g., Neon Transfection System [42] |

| Electroporation Buffer | Optimized solution for cell health and electroporation efficiency. | e.g., Buffer R [42] |

| Primary Cells | Target cells for editing. | e.g., CD34+ cells, iPSCs [42] |

| Cell Culture Media | For cell maintenance and recovery post-electroporation. | Serum-free expansion media recommended [42] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Guide RNA Preparation: Synthesize the target-specific guide RNA via in vitro transcription or purchase chemically synthesized sgRNA. For tracking, the gRNA can be fluorescently labeled by ligating a fluorophore (e.g., pCp-Cy5) to its 3' end using T4 RNA ligase [42].

- RNP Complex Assembly:

- Cell Preparation:

- Harvest the target cells (e.g., primary CD34+ cells) and wash them with an appropriate electroporation buffer or PBS.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in the electroporation buffer at a defined concentration (e.g., 150,000–250,000 cells per replicate) [42].

- Electroporation:

- Mix the cell suspension with the pre-assembled RNP complex.

- Load the mixture into an electroporation cuvette or tip.

- Electroporate using optimized parameters. For primary hematopoietic cells, parameters may range from 900 to 1,600 V, with specific pulse width and number [42].

- Post-Electroporation Recovery and Analysis:

- Immediately transfer the electroporated cells into pre-warmed culture media.

- Culture the cells and assess viability (e.g., via trypan blue exclusion) and transfection efficiency (via fluorescence if using labeled gRNA) after 24 hours.

- Analyze genome editing efficiency 72-96 hours post-electroporation, using methods like T7E1 assay, flow cytometry for fluorescent reporters, or next-generation sequencing [42].

Advanced Strategy: Ribozyme-Mediated Systems for Enhanced Specificity

A sophisticated method to further improve RNP and CRISPR applications involves ribozyme-mediated guide RNA production. This system uses self-cleaving ribozymes (like Hammerhead (HH) and Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV)) flanking the sgRNA sequence. When transcribed, the ribozymes self-cleave, producing sgRNAs with precise ends, which is critical for the activity of certain Cas enzymes like Cpf1 (Cas12a) [43] [44].

- Application: This strategy is particularly useful when using RNA polymerase II (Pol II) promoters, which allow for tissue-specific or inducible CRISPR editing, as opposed to the constitutive Pol III promoters (U6, U3) typically used for sgRNA expression [45]. The ribozymes process the transcript to generate a "clean" sgRNA without extra, potentially inhibitory, nucleotides at the ends.

- Benefit: Studies show that incorporating a 3'-terminal HDV ribozyme can boost the gene editing activity of the CRISPR-Cpf1 system by 1.1 to 5.2 fold [43].

Troubleshooting Guide and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: We are working with bovine zygotes and consistently observe high rates of genetic mosaicism. How can we adjust our protocol? A: The timing of delivery is critical. A key study demonstrated that microinjection of RNP complexes into oocytes before fertilization (0 hours post-insemination, hpi) or into zygotes at a very early stage (10 hpi) resulted in mosaicism rates of only ~10-30%. In contrast, the conventional injection time of 20 hpi, after DNA replication has begun, produced a 100% mosaicism rate [38]. Therefore, shifting to earlier delivery windows using RNPs is the most effective strategy.

Q2: Our primary T-cells are suffering high cell death after RNP electroporation. What can we optimize? A: High cell death is often related to electroporation parameters and cell health.

- Parameter Titration: Systematically titrate the voltage and pulse length. Start with a wide range (e.g., 900-1600V) and narrow down to the optimal setting for your specific cell type [42].

- RNP Dosage: Ensure you are not using a toxic excess of the RNP complex. Perform a dose-response curve to find the minimum effective amount.

- Cell Health: Use healthy, actively growing cells and ensure all buffers and media are fresh and at the correct pH and temperature. Post-electroporation recovery conditions are also critical.

Q3: How can we isolate successfully edited cells, especially when working with hard-to-transfect primary cells? A: A highly effective method is to use fluorescently labeled RNP complexes. Label the guide RNA with a fluorophore (like Cy5) via a ligation step. After electroporation, you can use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate the Cy5-positive cells, which have successfully taken up the RNP. Studies show that these sorted cells display significantly higher knockout efficiency compared to non-sorted transfected cells [42].

Q4: We are concerned about off-target effects. How does RNP delivery help, and what else can we do? A: RNP delivery inherently reduces off-target effects due to its short lifetime inside cells [39] [41]. For further reduction:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Employ engineered Cas9 proteins (e.g., Alt-R HiFi Cas9) with reduced off-target activity, which have been shown to work effectively in RNP format [39] [41].

- Optimize gRNA Design: Utilize computational tools to select gRNAs with high on-target and low off-target potential. Chemically modified gRNAs can also improve specificity and stability [39].

Visual Strategy: Timeline for Reducing Mosaicism

The following diagram contrasts the conventional plasmid delivery timeline with the optimized RNP strategy, highlighting how early RNP action prevents mosaicism.

The direct delivery of pre-assembled CRISPR RNP complexes represents a superior methodology for achieving efficient, rapid, and specific genome editing while effectively minimizing the persistent challenge of genetic mosaicism. By acting before DNA replication in zygotes and degrading quickly to limit off-target activity, RNP delivery aligns the kinetics of genome editing with the biological timing essential for generating non-mosaic, precisely modified organisms and primary cell lines. The integration of advanced strategies, such as ribozyme-mediated guide RNA production and fluorescent labeling for cell sorting, further enhances the power and precision of this approach, making it an indispensable tool for modern genetic research and therapeutic development.

A common and significant technical impediment in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing of zygotes is the high incidence of genetic mosaicism, where a single edited individual carries two or more cell lineages with different genotypes [3]. This occurs when editing events happen after the zygote has begun its initial divisions, leading to a mixture of edited and unedited cells within the same embryo [3]. Mosaicism presents a major obstacle for research and breeding programs because it can result in the inconsistent presentation of a desired trait and the potential absence of the intended edit in the animal's germline, complicating the establishment of stable genetic lines [3]. This technical support article explores two advanced alternatives—surrogate sire technology and blastomere separation—designed to circumvent this problem, providing scientists with reliable methods to achieve non-mosaic, heritable genetic modifications.

Direct editing of zygotes often leads to mosaic offspring because the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery may remain active and continue to cause edits after the first embryonic cell division [3]. The two alternative strategies discussed here bypass this issue in fundamentally different ways. Surrogate sire technology separates the gene editing process from the creation of the animal, by first editing cells in culture and then using these to produce gametes in a sterile host. Blastomere separation, conversely, involves editing at a very specific early embryonic stage and then physically separating the cells to trace the outcome.

The table below summarizes the core principles and key advantages of each approach.

Table: Comparison of Alternative Strategies to Overcome Mosaicism

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Sire Technology | Creation of sterile male animals (devoid of own germline) that produce sperm derived from transplanted, gene-edited donor spermatogonial stem cells [46] [47] [48]. | Enables mass dissemination of elite genetics from a single donor; eliminates mosaicism by editing cells prior to transplantation [47] [48]. | Livestock breeding programs; genetic conservation; dissemination of tailored genetics in aquaculture and terrestrial species [46] [48] [49]. |

| Blastomere Separation (2CC Method) | CRISPR-Cas9 injection into a single blastomere of a two-cell embryo, creating a chimeric organism where edited and wild-type cells can be directly compared, providing an internal control [50]. | Allows for the study of gene function in founder chimeric mice, bypassing the early lethality often associated with null mutations in essential genes [50]. | Functional genomics and developmental biology research, particularly for analyzing essential genes in founder animals [50]. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows of these two alternatives in contrast to the standard, mosaicism-prone zygote injection method.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Key Technical Hurdles

This section addresses frequently encountered experimental problems and provides evidence-based solutions to enhance the efficiency of your research.

Table: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low efficiency of complete gene knockout in zygotes | Use of a single sgRNA, leading to indels and mosaicism rather than complete exon deletion. | Use multiple (2-4) sgRNAs targeting a single key exon. This induces large-fragment deletions, promoting biallelic knockout. [51] | In mice and monkeys, using 3-4 sgRNAs targeting a single exon resulted in 100% and 91% complete knockout efficiency, respectively. [51] |

| Low germline transmission in surrogate sires | Incomplete sterilization of the host animal's germline, allowing host-derived sperm to contaminate the donor sperm population. | Use a complete, homozygous knockout of a fertility gene like NANOS2 for reliable, complete germline ablation. [46] [47] | NANOS2 KO males in mice, pigs, goats, and cattle were completely sterile but produced donor-derived sperm after transplantation. [47] [49] |

| Inefficient HDR and high NHEJ in embryos | The host cell's DNA repair machinery favors the error-prone NHEJ pathway over HDR. | Use small molecule enhancers (e.g., RS-1) to stimulate the HDR pathway (e.g., via Rad51) during the editing window. [3] | Research is ongoing, but using small molecules to modulate DNA repair pathways is a promising strategy to increase precise editing rates. [3] |

| Chimerism confounding analysis in blastomere-injected embryos | Difficulty in tracking which cells successfully incorporated the edit. | Co-inject CRISPR-Cas9 with Cre mRNA into a blastomere of a fluorescent reporter mouse line. This allows for lineage tracing of the edited cell population. [50] | The "2CC" method successfully traced wild-type and mutant cell lineages at different developmental stages, providing a robust internal control. [50] |

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies

Protocol: Surrogate Sire Production in Livestock

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating surrogate sire pigs, goats, or cattle, based on the work of Oatley et al. [47] [49].

Host Sterilization: