Prime Editing Explained: A Comprehensive Guide to the Next Generation of Precision Genome Engineering

This article provides a detailed exploration of prime editing, an advanced CRISPR-derived technology that enables precise genome modifications without double-strand breaks.

Prime Editing Explained: A Comprehensive Guide to the Next Generation of Precision Genome Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of prime editing, an advanced CRISPR-derived technology that enables precise genome modifications without double-strand breaks. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational mechanism of prime editors, their core components, and the step-by-step editing process. It further delves into methodological advancements from PE1 to PE7, therapeutic applications in diseases like Hurler syndrome and Tay-Sachs, and strategies to overcome challenges in efficiency and delivery. The content also includes a comparative analysis with base editing and CRISPR-Cas9, validating prime editing's superior precision and expanding clinical potential.

The Foundation of Prime Editing: From CRISPR-Cas9 to a Precision Gene Editor

The Limitation of First-Generation CRISPR and the Need for Precision

First-generation CRISPR-Cas9 technology revolutionized genetic engineering by providing unprecedented control over genome modification. However, this approach relies on creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which activates error-prone cellular repair mechanisms that frequently lead to unintended mutations [1]. These DSBs trigger predictable but problematic cellular responses: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, while homology-directed repair (HDR) can produce precise edits but with relatively low efficiency in most cell types [2]. The consequences extend beyond simple inefficiency—DSB generation can activate the p53-mediated DNA damage response pathway, leading to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, or cellular senescence [1]. Furthermore, chromosomal rearrangements, including translocations and large deletions, present significant safety concerns that substantially limit therapeutic applications [1]. These limitations highlighted an urgent need for more precise genetic modification technologies that could achieve predictable outcomes without inducing DNA breakage, spurring the development of precision editing tools like base editing and prime editing.

The Evolution of Precision Editing Tools

Base Editing: Foundations of Precision

Base editing emerged as the first major alternative to DSB-dependent editing, utilizing catalytically impaired Cas9 fused to nucleobase deaminase enzymes to enable direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without breaking the DNA backbone [1]. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) convert C•G to T•A base pairs, while adenine base editors (ABEs) convert A•T to G•C base pairs [3]. This approach significantly reduces indel formation compared to CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases and enables high-efficiency editing in both dividing and non-dividing cells [1]. However, base editing faces substantial constraints, including a narrow editing window (typically 4-5 nucleotides), strict PAM sequence requirements, and the potential for bystander edits where adjacent bases within the editing window are unintentionally modified [1]. Most significantly, base editors cannot achieve all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, nor can they perform targeted insertions or deletions, restricting their application scope [4]. These limitations prompted the development of a more versatile precision editing platform.

Prime Editing: A Search-and-Replace Mechanism

Prime editing represents a paradigm shift in precision genome editing by functioning as a "search-and-replace" system that directly writes new genetic information into a target DNA site without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates [1] [4]. The core prime editing machinery consists of two primary components: (1) a prime editor protein formed by fusing a Cas9 nickase (H840A) to an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT), and (2) a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit [1] [4]. The editing process occurs through a coordinated multi-step mechanism beginning with target recognition and strand nicking, followed by reverse transcription of the edit-encoding RNA template, and culminating with DNA flap resolution and mismatch repair to permanently incorporate the genetic change [4]. This molecular architecture enables prime editing to perform all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, plus small insertions, deletions, and combinations thereof, dramatically expanding the range of addressable genetic variants compared to previous technologies [1] [4].

Prime Editing Mechanism: Molecular Workflow

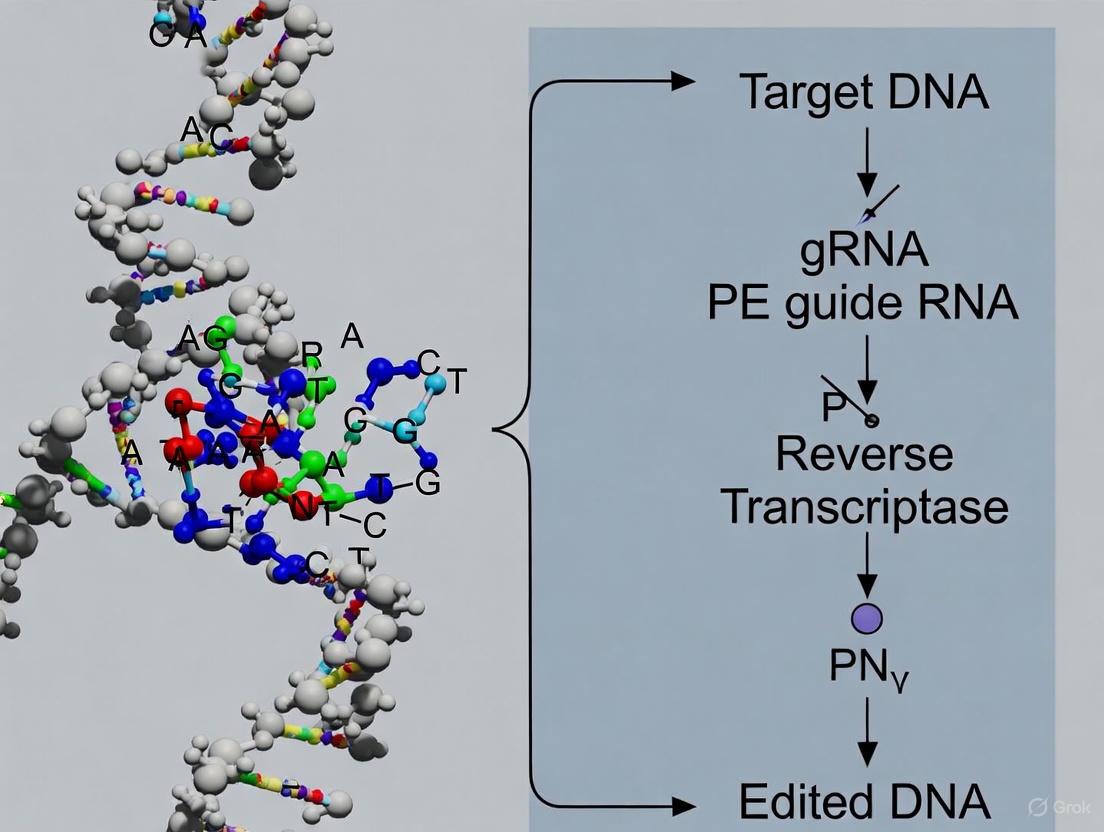

The prime editing process operates through a precise biochemical pathway that can be visualized in the following workflow and described in detail thereafter:

Diagram 1: Prime editing molecular workflow. The process begins with complex assembly and proceeds through six key steps to achieve precise genome modification.

Component Architecture and Target Recognition

The prime editor fusion protein combines a Cas9 nickase (nCas9) with a reverse transcriptase (RT) domain, typically derived from Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) [5]. The nCas9 component contains a H840A mutation that inactivates the HNH nuclease domain, enabling only single-strand nicking rather than DSB formation [1] [4]. The pegRNA consists of four critical regions: (1) a spacer sequence that directs target recognition through standard Cas9:RNA DNA binding mechanics; (2) a scaffold region that facilitates Cas9 binding; (3) a primer binding site (PBS) that anneals to the nicked DNA strand; and (4) an RT template containing the desired edit [4] [3]. The initial binding event relies on canonical Cas9:gRNA DNA recognition, requiring a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (typically 5'-NGG-3') adjacent to the target site [5].

DNA Nicking and Reverse Transcription

Upon binding to the target DNA, the nCas9 component introduces a single-strand nick at a specific position 3 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence on the non-target strand [5]. The newly liberated 3' DNA end then hybridizes with the complementary PBS sequence on the pegRNA, forming a primer-template complex that initiates reverse transcription [4]. The RT enzyme synthesizes DNA using the RT template region of the pegRNA, creating a complementary DNA flap containing the desired genetic edit [1]. This reverse transcription process continues until the entire edit sequence has been copied, resulting in a free 3' DNA flap that contains the newly written genetic information [4].

DNA Flap Resolution and Edit Incorporation

The newly synthesized edited DNA flap competes with the original 5' DNA flap for incorporation into the genome [4]. Cellular repair machinery recognizes and removes the unedited 5' flap while preferentially incorporating the edited 3' flap through a DNA ligation process [1]. This results in a heteroduplex DNA molecule with one strand containing the edit and the complementary strand retaining the original sequence [5]. The mismatch repair (MMR) system then recognizes this DNA mismatch and randomly resolves it using either strand as a template, resulting in permanent edit incorporation in approximately 50% of cases [1]. To bias this resolution toward the edited strand, the PE3 system introduces a second nicking guide RNA (ngRNA) that directs nCas9 to nick the non-edited strand, triggering repair that preferentially uses the edited strand as a template and increasing editing efficiency up to 4.2-fold [4].

Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

The rapid advancement of prime editing technology has produced multiple generations of editors with progressively improved capabilities, as summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

| Editor | Key Components | Editing Efficiency | Key Innovations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | nCas9 (H840A) + M-MLV RT | ~10-20% [1] | Proof-of-concept system | Initial demonstration of search-and-replace editing [1] |

| PE2 | nCas9 + engineered RT (5 mutations) | ~20-40% [1] | Optimized RT with enhanced processivity and stability [1] | Broad research applications; foundation for later systems [1] |

| PE3 | PE2 + additional sgRNA for non-edited strand nicking | ~30-50% [1] | Dual nicking strategy to bias MMR toward edited strand [1] [4] | High-efficiency editing in therapeutic contexts [1] |

| PEmax | Codon-optimized nCas9 (R221K/N394K) + optimized NLS | 50-95% (with MMR inhibition) [6] | Enhanced nuclear localization and expression [5] | High-efficiency editing in challenging cell types [5] |

| PE5 | PEmax + MLH1dn (MMR inhibition) | ~60-80% [1] | MMR suppression to prevent edit reversal [1] | Therapeutic applications requiring high editing rates [1] |

| PE6 | Compact RT variants (PE6a/b/c) or evolved M-MLV (PE6d) | ~70-90% [1] | Phage-assisted evolution for specialized editing tasks [1] [5] | Large insertions; challenging edits [1] [5] |

Later-generation editors have addressed specific limitations through creative molecular solutions. The PE4 and PE5 systems incorporate dominant-negative MLH1 (MLH1dn) to suppress MMR activity, significantly improving editing efficiency by preventing the removal of newly incorporated edits [1]. The PE6 platform represents a suite of editors featuring compact RTs (PE6a, PE6b, PE6c) for improved delivery or highly processive RTs (PE6d) for complex edits [1] [5]. Recent innovations have also produced Cas12a-based prime editors that recognize T-rich PAM sequences, expanding the targeting scope, and twinPE systems that use paired pegRNAs for larger edits [1] [7].

Experimental Framework for Prime Editing

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Prime Editing Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Editor Proteins | PE2, PEmax, PE5, PE6 variants [1] [5] | Core editing machinery with varying efficiencies and specialties |

| Delivery Systems | Engineered virus-like particles (eVLP) [7], Lentiviral vectors [6], Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [3] | Cellular delivery of editing components |

| pegRNA Modifications | epegRNA (tevopreQ1 motif) [6], Circular pegRNA [1] | Enhanced pegRNA stability and editing efficiency |

| MMR Modulators | MLH1dn [1], Small molecule inhibitors | Suppress mismatch repair to improve editing outcomes |

| Cell Lines | MMR-deficient lines (e.g., MLH1-KO) [6], Stable editor-expressing lines [6] | Provide optimized cellular environment for editing |

| Analysis Tools | Next-generation sequencing, EditR, Primerize [8] | Quantify editing efficiency and specificity |

Protocol for High-Efficiency Prime Editing

The following experimental workflow illustrates the process for achieving high-efficiency prime editing based on established protocols:

Diagram 2: High-efficiency prime editing protocol. The seven-step workflow progresses from initial design to final validation of precise edits.

Step 1: Target Selection and pegRNA Design Identify target sites with appropriate PAM sequences (NGN for SpCas9-based editors) and design pegRNAs with systematic variation in PBS length (8-15 nt) and RT template length (10-30 nt) [6] [8]. Incorporate 3' structural motifs (e.g., tevopreQ1) to enhance pegRNA stability, creating engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) that significantly improve editing efficiency [6].

Step 2: Editor Selection Choose an appropriate prime editor based on the specific application: PE2 for basic editing, PEmax for general high-efficiency editing, PE5 when MMR antagonism is problematic, or PE6 variants for specialized tasks [1] [5]. For therapeutic applications requiring viral delivery, consider compact editors like PE6a or PE6b (1.2-1.5 kb) to accommodate packaging constraints [5].

Step 3: Delivery System Optimization Select delivery methods based on the target cell type and application. For research cell lines, lentiviral transduction provides efficient delivery and stable expression [6]. For therapeutic applications, engineered virus-like particles (eVLPs) offer transient expression with reduced immunogenicity [7]. Recent eVLP systems have achieved 65-fold improvements in delivery efficiency compared to earlier iterations [7].

Step 4: MMR Modulation Inhibit MMR activity to prevent edit rejection, either by using MMR-deficient cell lines (e.g., MLH1-KO) [6] or by co-expressing dominant-negative MMR proteins (e.g., MLH1dn in PE5) [1]. This critical step can improve editing efficiency up to 7-fold, particularly for small substitutions that MMR recognizes more efficiently [4].

Step 5: Stable Expression Establishment Generate cell lines with stable prime editor expression integrated into safe harbor loci (e.g., AAVS1) to enable continuous editing over multiple cell divisions [6]. Co-express fluorescent markers (e.g., EGFP) to track editor expression and facilitate cell sorting [6]. Allow extended editing periods (14-28 days) for edit accumulation, with efficiency monitoring at regular intervals [6].

Step 6: Editing Efficiency Quantification Harvest genomic DNA and amplify target loci using PCR, followed by next-generation sequencing to quantify precise editing rates and error profiles [6] [8]. Calculate precise editing efficiency as the percentage of sequencing reads containing only the intended edit without errors [6].

Step 7: Off-Target Analysis and Validation Perform whole-genome sequencing or targeted sequencing of predicted off-target sites to assess editing specificity [1] [4]. Compare editing outcomes with negative control cells to distinguish background mutations from true off-target events [6].

Current Limitations and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, prime editing faces several technical challenges that require further innovation. Delivery remains a primary constraint due to the large size of editor proteins and the complexity of pegRNAs, complicating packaging into delivery vectors with limited capacity, particularly adeno-associated viruses [4] [3]. Editing efficiency varies substantially across genomic loci and cell types, influenced by factors such as chromatin accessibility, DNA repair dynamics, and cellular state [8]. The MMR system continues to present a significant barrier, particularly for small edits that it efficiently recognizes and removes [6] [4]. Additionally, pegRNA design optimization remains partially empirical, requiring testing of multiple designs for each target to achieve optimal efficiency [8].

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas: (1) creating smaller editors through alternative Cas proteins and compact RTs to improve deliverability [1] [5]; (2) developing more sophisticated MMR evasion strategies through engineered editors or small molecule inhibitors [4]; (3) enhancing pegRNA stability and function through advanced chemical modifications and structural optimizations [6]; and (4) employing machine learning approaches to better predict editing outcomes based on sequence context and cellular environment [8]. As these technical hurdles are addressed, prime editing is poised to become an increasingly powerful tool for both basic research and therapeutic applications, potentially enabling correction of a broad spectrum of genetic mutations underlying human disease.

The transition from first-generation CRISPR to precision editing technologies represents a fundamental shift in our approach to genome engineering. By moving beyond double-strand breaks and their associated limitations, prime editing provides researchers with an unprecedentedly precise tool for writing genetic information. While challenges remain, the rapid evolution of this technology continues to expand its capabilities and applications, offering new pathways for understanding genetic function and developing transformative genetic medicines.

Prime editing represents a significant leap forward in the field of precision genome editing, enabling precise genetic modifications without inducing double-strand breaks (DSBs) or requiring donor DNA templates [9]. This technology has rapidly evolved into a versatile tool supporting a wide range of genetic modifications, including point mutations, insertions, and deletions. The core of this system is the prime editor protein complex, a sophisticated molecular machine that combines targeting and enzymatic functions to rewrite genetic information with exceptional accuracy. Understanding the architecture and function of this complex is fundamental for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to harness prime editing for therapeutic applications and basic research.

Architectural Composition of the Core Complex

Molecular Components and Their Functions

The prime editor protein complex is a multi-component system engineered to perform precise DNA editing through a coordinated mechanism. The core complex consists of a protein component and a specialized RNA guide that work in concert to identify target sequences and execute edits [9] [3].

Table 1: Core Components of the Prime Editing Complex

| Component | Type | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nickase (H840A) | Protein | Binds and nicks target DNA | Creates single-strand break; Does not cause double-strand breaks [9] [3] |

| Engineered Reverse Transcriptase (RT) | Protein | Synthesizes DNA from RNA template | Fused to Cas9 nickase; Uses pegRNA template for DNA synthesis [9] [3] |

| Prime Editing Guide RNA (pegRNA) | RNA | Target recognition & edit template | Combines sgRNA spacer with RT template and primer binding site [9] [3] |

The fusion of a Cas9 nickase (H840A) with an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) from Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MMLV) forms the protein backbone of the editor [9] [3]. This fusion creates a single polypeptide chain that can both locate a specific DNA sequence and catalyze the synthesis of new DNA at that site. The Cas9 nickase component is responsible for DNA binding and introduces a single-strand break in the non-target DNA strand, while the reverse transcriptase utilizes an RNA template to synthesize new DNA containing the desired edit.

Figure 1: Architecture of the prime editor complex, showing the fusion of Cas9 nickase and reverse transcriptase proteins guided by a multi-functional pegRNA.

The pegRNA: Blueprint and Guidance System

The prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) is a critical component that distinguishes prime editing from other CRISPR-based systems. Unlike conventional single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) used in standard CRISPR-Cas9 editing, the pegRNA serves dual functions: it directs the complex to the target DNA sequence and provides the template for the new genetic sequence to be written [3].

The pegRNA consists of four essential regions [3]:

- Spacer sequence: A ~20 nucleotide sequence that binds to the complementary target DNA locus, guiding the complex to the specific site for editing.

- Scaffold sequence: Enables binding to the Cas9 nickase protein and formation of the ribonucleoprotein complex.

- Reverse Transcription Template (RTT): Encodes the desired edit and provides flanking homology to facilitate the editing process, typically 25-40 nucleotides in length.

- Primer Binding Site (PBS): A 10-15 nucleotide sequence that anneals to the nicked DNA strand to initiate reverse transcription.

The extended length of pegRNAs (typically 120-145 nucleotides, but potentially up to 170-190 nucleotides) presents challenges for synthesis, delivery, and stability, which researchers must address through optimized design and delivery strategies [3].

Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

Development from PE1 to PE7

The prime editing system has undergone significant evolution since its initial development, with successive generations offering improved efficiency and versatility. The journey began with PE1, which established the foundational proof-of-concept by coupling nCas9 (H840A) with reverse transcriptase to mediate editing, though with relatively limited efficiency [9].

Table 2: Evolution of Prime Editor Systems

| System | Key Improvements | Typical Editing Efficiency | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Foundational system: nCas9 (H840A) + MMLV-RT | Low (Baseline) | Proof-of-concept edits [9] |

| PE2 | Engineered RT with enhanced thermostability and processivity | 1.7-7.6x PE1 (Human cells) | Broad range of precise edits [9] |

| PE3 | Additional nicking sgRNA to edit complementary strand | 1.4-8.2x PE2 (Human cells) | High-efficiency editing [9] |

| PE7 | Fusion with La protein + optimized pegRNA | 6.8-11.5x PE2 (Zebrafish) | In vivo therapeutic applications [10] |

PE2 incorporated an engineered reverse transcriptase with mutations that enhanced thermostability, processivity, and affinity for RNA-DNA hybrid substrates, resulting in significantly improved editing outcomes [9]. PE3 further augmented efficiency by incorporating an additional sgRNA that nicks the non-edited DNA strand, encouraging the cellular repair machinery to use the newly synthesized edited strand as a template, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful edit incorporation [9]. The most advanced systems, including PE7, represent substantial leaps forward through fusion with accessory proteins like La, which stabilizes the editing complex and enhances efficiency, particularly when combined with engineered "La-accessible" pegRNAs containing polyU motifs [10].

Engineering Advances in Protein Components

Recent engineering efforts have focused on optimizing the protein components to enhance editing precision and reduce unwanted byproducts. A significant concern with earlier prime editors was the potential for the nCas9 (H840A) to inadvertently generate double-strand breaks, leading to unwanted insertions or deletions (indels). This limitation has been addressed through additional mutations such as N863A, which significantly reduces the enzyme's ability to create DSBs while maintaining efficient target editing [9].

Further innovations include the development of split prime editors (sPE) that separate nCas9 and RT into independently functioning units [9]. This approach not only maintains high precision but also facilitates delivery via dual AAV vector systems, addressing a significant challenge in therapeutic applications. In vivo demonstrations have shown promising results, including successful editing of the β-catenin gene in mouse liver and correction of a mutation in a mouse model of type I tyrosinemia [9].

Quantitative Performance Data

Efficiency and Fidelity Metrics

The performance of prime editing systems is quantified through multiple parameters, including editing efficiency (percentage of target cells successfully edited), purity (percentage of desired edits among all editing outcomes), and error rate (frequency of unintended modifications).

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Advanced Prime Editing Systems

| System | Editing Efficiency | Error Rate | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE2 | Baseline (varies by locus) | Not specifically quantified | Human cell lines [9] |

| PE7 with La-accessible pegRNA | Up to 15.99% (6.8-11.5x PE2) | Not specifically quantified | Zebrafish embryos (RNP delivery) [10] |

| vPE (Variant PE) | Not specified | 1.7% (1 in 101 edits) to 0.18% (1 in 543 edits) | Mouse and human cells [11] |

| PERT System | 20-70% of normal enzyme activity restored | No detected off-target edits | Human cell models of Batten, Tay-Sachs, and Niemann-Pick diseases [12] |

Recent advances have substantially improved both efficiency and fidelity. The development of vPE, which incorporates mutated Cas9 proteins that destabilize the old DNA strands during editing, has dramatically reduced error rates from approximately one error in seven edits to as low as one error in 543 edits for high-precision modes [11]. In therapeutic contexts, the PERT (prime editing-mediated readthrough of premature termination codons) system has demonstrated impressive efficacy in restoring protein function across multiple disease models with no detected off-target edits or significant transcriptomic changes [12] [13].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Delivery

The delivery of prime editing components as pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes represents a highly efficient approach for introducing editors into cells, particularly for in vivo applications. The workflow involves several critical steps [10]:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for prime editing using RNP complex delivery in zebrafish embryos, demonstrating a common approach for in vivo gene editing.

- RNP Complex Assembly: Purified PE7 protein is incubated with synthetic La-accessible pegRNA at specific concentrations (typically 750 ng/μL PE7 protein with 240 ng/μL pegRNA) to form functional RNP complexes [10].

- Microinjection: Approximately 2 nL of the RNP complex is delivered into the yolk cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos using microinjection techniques [10].

- Embryo Culture: Injected embryos are maintained at 28.5°C in a controlled environment to ensure proper development [10].

- Sample Collection: At 2 days post-fertilization (dpf), normally developed embryos are selected and collected for analysis [10].

- Genomic Analysis: DNA is extracted from pooled embryos (typically 6-8 per experimental group) using commercial kits, followed by target amplification with barcoded primers and next-generation sequencing to quantify editing efficiency [10].

This RNP delivery approach minimizes off-target effects and reduces potential immune responses compared to plasmid-based delivery methods, as the editing complexes are active for a shorter duration and degrade naturally within cells.

In Vivo Therapeutic Application

The PERT (Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough of Premature Termination Codons) system demonstrates a sophisticated therapeutic application of prime editing. This approach involves installing an engineered suppressor tRNA (sup-tRNA) to enable readthrough of premature stop codons, potentially treating multiple genetic diseases with a single editor [12] [13].

The experimental protocol involves [13]:

- tRNA Engineering: Screening tens of thousands of variants of all 418 human tRNAs to identify optimal sup-tRNA candidates through iterative optimization of leader sequences, tRNA sequences via saturation mutagenesis, and terminator sequences.

- Cell Model Validation: Testing optimized prime editors in human cell models of Batten disease (TPP1 p.L211X and p.L527X), Tay-Sachs disease (HEXA p.L273X and p.L274X), and Niemann-Pick disease type C1 (NPC1 p.Q421X and p.Y423X) using enzyme activity assays.

- In Vivo Testing: Delivering editors to mouse models of Hurler syndrome (IDUA p.W392X) via appropriate vectors and measuring protein restoration (approximately 6% IDUA enzyme activity) and pathological improvement.

This disease-agnostic approach demonstrates the potential for single editing compositions to treat multiple disorders caused by nonsense mutations, which account for approximately 24% of pathogenic alleles in the ClinVar database [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Prime Editing Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Plasmids | Express editor proteins in cells | PE2, PE3, PEmax, PE7 backbones [9] [10] |

| pegRNA Synthesis | Guide and template for editing | Chemically synthesized with 5'/3' modifications (methylated or phosphorothioate linkages) for stability [10] |

| La-accessible pegRNA | Enhanced stability and efficiency | pegRNA with 3' polyU motif for improved La protein binding [10] |

| Delivery Vectors | Introduce components into cells | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), AAV vectors (for split systems), electroporation systems [9] [3] |

| NGS Validation Kits | Quantify editing efficiency | Barcoded primers for amplicon sequencing; Illumina platforms [10] |

| Cell Culture Models | Test editing in human context | HEK293T, primary human fibroblasts, disease-specific cell models [9] [13] |

| Animal Models | In vivo functional testing | Zebrafish embryos, mouse disease models (e.g., Hurler syndrome) [13] [10] |

The research toolkit for prime editing has expanded significantly, with critical reagents spanning from editor expression constructs to specialized pegRNAs and delivery systems. Plasmid systems encoding various prime editor versions (PE2, PE3, PE7) are fundamental for initial testing and optimization [9] [10]. Specialized pegRNAs, particularly engineered versions with modified termini (evopreQ, mpknot, or polyU motifs), significantly enhance editing efficiency by protecting against degradation and improving protein binding [9] [10].

Delivery remains a crucial consideration, with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) emerging as a promising vehicle for in vivo therapeutic applications, particularly for liver-targeted edits [9] [14]. For complex editors exceeding AAV packaging limits, split systems such as sPE (split prime editors) enable dual-vector delivery while maintaining functionality [9]. Validation reagents, including barcoded primers for high-throughput sequencing and specific antibody assays for functional validation, complete the essential toolkit for rigorous prime editing research.

Prime editing represents a transformative advancement in precision genome editing, enabling targeted installation of base substitutions, insertions, and deletions without requiring double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or donor DNA templates [9] [15]. At the heart of this versatile technology lies the prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA), a sophisticated molecular blueprint that directs both the targeting and the execution of precise genetic modifications [3]. Unlike conventional single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) used in CRISPR-Cas9 systems that merely specify the target location, pegRNAs additionally encode the desired edit and provide the necessary components for its implementation through reverse transcription [16] [3]. This multi-functional molecule has redefined the possibilities of genome engineering, offering researchers unprecedented control over genetic outcomes. The critical importance of pegRNA design and optimization cannot be overstated, as it directly determines the efficiency and success of prime editing experiments across diverse applications from therapeutic development to agricultural improvement [17] [18]. This technical guide deconstructs the pegRNA to provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for leveraging this powerful technology in their experimental systems.

Architectural Components of the pegRNA

The pegRNA comprises four essential sequence components that function in concert to enable precise genome editing. Each element serves a distinct purpose in the prime editing mechanism, and optimal design of each is crucial for achieving high editing efficiency.

Spacer Sequence: This 20-nucleotide region located at the 5' end of the pegRNA dictates target specificity by binding to the complementary DNA strand, guiding the prime editor complex to the intended genomic locus [3] [19]. The spacer sequence must be carefully selected to minimize off-target effects while maintaining strong on-target activity, with tools like the Doench 2016 score providing predictive efficiency metrics [19].

scaffold Structure: This section forms the stable secondary structure that binds the Cas9 nickase (nCas9) component of the prime editor, enabling its proper positioning and function at the target site [3]. The scaffold remains largely consistent with traditional sgRNA architectures but must accommodate the additional 3' extensions unique to pegRNAs.

Primer Binding Site (PBS): Typically 10-15 nucleotides in length, the PBS serves as an anchor point by binding to the 3' end of the nicked DNA strand, creating the primer-template complex that initiates reverse transcription [15] [20]. The PBS length and sequence significantly influence editing efficiency, with optimization required for different target contexts.

Reverse Transcription Template (RTT): This critical component encodes the desired genetic edit(s) and flanking homology region, serving as the template for the reverse transcriptase enzyme to synthesize the edited DNA strand [16] [3]. The RTT typically ranges from 25-40 nucleotides depending on the complexity of the intended edit, balancing the need for sufficient homology with synthetic constraints.

Table 1: Core Components of the pegRNA and Their Functions

| Component | Length (nt) | Primary Function | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spacer | ~20 | Target recognition and binding | Minimize off-targets; maximize on-target efficiency |

| Scaffold | ~70-80 | Cas9 nickase binding | Maintain structural integrity for editor complex formation |

| PBS | 10-15 | Initiation of reverse transcription | Optimize length for binding strength and specificity |

| RTT | 25-40+ | Template for desired edit | Include edit with sufficient flanking homology |

The complete pegRNA molecule generally ranges from 120-145 nucleotides, significantly longer than standard sgRNAs, which presents both design and delivery challenges [3]. The extended length can complicate synthetic production, reduce cellular stability, and hinder delivery via viral vectors, necessitating specialized optimization strategies.

Molecular Mechanism of pegRNA-Directed Editing

The pegRNA orchestrates a sophisticated multi-step editing process through coordinated interactions with both the prime editor protein and the target DNA. Understanding this mechanism is essential for effective experimental design and troubleshooting.

Target Recognition and Complex Assembly

The process initiates with the formation of the prime editor-pegRNA complex, wherein the Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion protein associates with the pegRNA scaffold region [3] [20]. The spacer sequence then directs this complex to the complementary target DNA site, with successful binding requiring both sequence complementarity and the presence of an appropriate protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [19].

DNA Nicking and Primer Binding

Upon target binding, the Cas9 nickase component cleaves the PAM-containing DNA strand, generating a single-strand break with an exposed 3'-hydroxyl group [16] [20]. This nicked strand then serves as a primer for the subsequent reverse transcription step, with initiation dependent on hybridization between the primer binding site (PBS) of the pegRNA and the complementary sequence on the nicked DNA flap [15].

Reverse Transcription and Edit Incorporation

The reverse transcriptase enzyme utilizes the RNA-based RTT as a template to synthesize a new DNA strand extending from the primed 3' end, incorporating the desired edit specified in the RTT sequence [9] [3]. This results in a DNA heteroduplex intermediate containing both the original unedited strand and the newly synthesized edited strand, which exists as a 3' flap structure competing with the original 5' flap for integration [20].

Flap Resolution and Strand Correction

Cellular repair machinery processes the heteroduplex intermediate, preferentially removing the unedited 5' flap and ligating the edited 3' flap into the genomic DNA [15] [3]. For permanent incorporation of the edit in both DNA strands, additional systems like PE3 and PE3b introduce a second nick in the non-edited strand using a standard sgRNA, biasing cellular repair to use the edited strand as a template and resulting in a fully edited DNA duplex [16] [15].

Diagram 1: pegRNA Mechanism Flow - The sequential molecular steps of pegRNA-directed prime editing

Quantitative Design Parameters and Optimization Strategies

Systematic optimization of pegRNA components has yielded significant improvements in prime editing efficiency. The following parameters represent critical design considerations supported by empirical data.

Primer Binding Site (PBS) Optimization

The PBS length directly influences binding stability and reverse transcription initiation efficiency. Both excessively short and excessively long PBS sequences can impair editing efficiency, with optimal length depending on specific experimental context [20].

Reverse Transcription Template (RTT) Design

The RTT must balance two competing priorities: containing sufficient homology to facilitate proper flap equilibration and integration, while minimizing length to reduce synthetic complexity and potential degradation [15] [20]. Studies demonstrate that RTT length strongly influences editing efficiency, particularly in plant systems [20].

pegRNA Engineering for Enhanced Stability

A significant advancement in pegRNA technology came with the development of engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs), which incorporate structured RNA motifs at the 3' end to protect against exonuclease degradation [9] [17]. These motifs include evopreQ1, mpknot, and Zika virus exoribonuclease-resistant RNA motifs (xr-pegRNA), which typically improve editing efficiency by 3-4-fold across diverse cell types [9].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Optimization Parameters for pegRNA Components

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Efficiency | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS length | 10-15 nt | Critical: <8nt insufficient binding; >16nt increased off-target effects | [15] [20] |

| RTT length | 25-40 nt | Strong effect: Shorter templates reduce efficiency; longer templates increase degradation | [15] [20] |

| RTT GC content | 30-70% | Moderate: Extreme values may impair functionality | [20] |

| epegRNA motifs | evopreQ1, mpknot | High: 3-4 fold improvement in mammalian cells | [9] [17] |

| Nicking sgRNA position | 40-100 nt from pegRNA nick | Variable: Dependent on edit type and cellular context | [15] |

Recent benchmarking studies utilizing stable expression of PEmax and epegRNAs in DNA mismatch repair-deficient cells have demonstrated remarkably high efficiencies, achieving up to 95% precise editing for certain targets [17]. These optimized conditions highlight the cumulative impact of synergistic improvements in pegRNA design, editor architecture, and cellular environment manipulation.

Experimental Protocol for pegRNA Design and Testing

This section provides a detailed methodology for designing, constructing, and validating pegRNAs for prime editing applications in mammalian cells, incorporating best practices from established protocols [15] [21].

pegRNA Design Workflow

Target Site Selection: Identify potential target sites adjacent to appropriate PAM sequences (5'-NGG-3' for standard Cas9) within 50 base pairs of the intended edit location [15] [19]. Verify target uniqueness using genome alignment tools to minimize off-target effects.

Spacer Design: Select a 20-nucleotide spacer sequence with high predicted on-target efficiency using established scoring algorithms (e.g., Doench 2016 score) [19]. Avoid spacers with potential off-target sites having fewer than 3 mismatches to the intended target.

PBS and RTT Determination: Design multiple pegRNAs (typically 3-5) with varying PBS lengths (10-15 nt) and RTT configurations for empirical testing [15] [21]. The RTT should encode the desired edit flanked by sufficient homology (typically 10-15 nt on each side) to support flap equilibration.

Nicking sgRNA Design (for PE3/PE5 systems): Design additional standard sgRNAs that target the non-edited strand, positioned 40-100 base pairs from the pegRNA-induced nick [15]. For PE3b systems, design nicking sgRNAs whose protospacer overlaps with the edit site to enhance specificity.

Diagram 2: pegRNA Design Workflow - Sequential process for designing and optimizing pegRNAs

pegRNA Cloning and Delivery

Molecular Cloning: Clone pegRNA expression cassettes into appropriate vectors using BsaI or BbsI restriction sites for golden gate assembly [21]. For epegRNAs, include structured RNA motifs (e.g., tevopreQ1) at the 3' terminus of the pegRNA scaffold.

Vector Selection: Utilize optimized prime editor systems such as PEmax (with codon-optimized RT and Cas9) for enhanced expression and nuclear localization [15] [17]. For challenging edits, consider PE4/PE5 systems that incorporate dominant negative MLH1 (MLH1dn) to suppress mismatch repair and improve efficiency [15] [17].

Cell Transfection: Deliver pegRNA and prime editor constructs to target cells using appropriate methods (electroporation for primary cells, lipid nanoparticles for difficult-to-transfect cells) [21] [3]. For stable expression systems, utilize lentiviral transduction with selection markers.

Efficiency Validation and Analysis

Next-Generation Sequencing: Assess editing efficiency 3-7 days post-transfection by PCR amplification of the target region followed by Illumina MiSeq sequencing [21]. Analyze sequence data for precise edits, indels, and other byproducts.

Clone Isolation and Characterization: For stable integration studies, isolate single-cell clones and expand for comprehensive genotyping via Sanger sequencing and functional validation [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for pegRNA Implementation

Successful implementation of prime editing requires access to specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogues essential research reagents for pegRNA experimentation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for pegRNA Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| PEmax vector | Optimized prime editor with enhanced expression and nuclear localization | Addgene (#132775) [15] |

| pegRNA cloning vector | Backbone for pegRNA expression with U6 promoter | Addgene (#132777) [21] |

| epegRNA motifs | Structured RNA elements for pegRNA stabilization | [9] [17] |

| MLH1dn expression vector | Dominant negative MMR protein to enhance editing efficiency | Addgene (PE4/PE5 systems) [15] |

| p53DD expression vector | p53 dominant negative fragment to boost efficiency in hPSCs | Addgene (#41856) [21] |

| multicrispr R package | Computational tool for pegRNA design and off-target analysis | Bioconductor [19] |

The pegRNA represents both the targeting mechanism and the molecular blueprint for prime editing, integrating multiple functions into a single RNA molecule. Its sophisticated architecture—combining spacer, scaffold, PBS, and RTT components—enables precise "search-and-replace" genome editing without requiring double-strand breaks or donor DNA templates [16] [3]. While pegRNA technology has faced challenges related to variable efficiency and delivery, ongoing optimization strategies including epegRNA engineering, mismatch repair inhibition, and improved delivery systems have substantially enhanced its performance and reliability [9] [17] [18]. As prime editing continues to evolve toward therapeutic and agricultural applications, the pegRNA remains at the center of this revolutionary technology, offering researchers unprecedented precision in genome engineering. The design principles and experimental frameworks outlined in this guide provide a foundation for harnessing this powerful tool to address diverse genetic challenges.

The Fundamental 'Search-and-Replace' Mechanism

Prime editing represents a transformative advancement in genome engineering, offering unprecedented precision and versatility for genetic modifications. As a "search-and-replace" technology for the genome, it enables precise insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible base substitutions without requiring double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or external donor DNA templates [22] [23]. This groundbreaking approach significantly expands the therapeutic potential of genome editing while minimizing the risks of unintended mutations and genomic instability that can accompany conventional CRISPR-Cas9 systems [11].

The technology was developed to address critical limitations in existing genome-editing tools. While conventional CRISPR-Cas9 primarily generates insertions and deletions (indels) through DSB repair, and base editing is restricted to specific types of nucleotide substitutions, prime editing combines the programmability of CRISPR with the precision of reverse transcription to achieve a wider range of genetic modifications [22]. This versatility is particularly valuable for therapeutic applications, where precisely correcting pathogenic mutations requires high fidelity and minimal off-target effects. As noted by MIT researchers, "In principle, this technology could eventually be used to address many hundreds of genetic diseases by correcting small mutations directly in cells and tissues" [11].

Core Molecular Mechanism

The prime editing system consists of two primary components: a prime editor protein and a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [22] [23]. The editor protein is a fusion of a Cas9 nickase (nCas9) and a reverse transcriptase enzyme. The nCas9 component contains a H840A mutation that renders it capable of nicking only a single DNA strand, unlike wild-type Cas9 which creates double-strand breaks [23]. The reverse transcriptase domain, typically derived from Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV RT), synthesizes DNA complementary to the RNA template provided by the pegRNA [22].

The pegRNA serves dual functions: it directs the nCas9 to a specific genomic locus and also templates the desired genetic modification [23]. Beyond the standard CRISPR guide RNA sequence that specifies the target site, the pegRNA contains two critical extensions at its 3′ end: a primer binding site (PBS) and a reverse transcription (RT) template encoding the desired edit [22] [23]. The editing process initiates when the nCas9 domain binds to the target DNA and nicks the strand containing the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [23]. The exposed 3′ end of the nicked DNA then hybridizes with the PBS region of the pegRNA, positioning it for reverse transcription [22]. The reverse transcriptase subsequently synthesizes a new DNA flap using the RT template as a guide, generating the programmed genetic modification [23]. Cellular repair mechanisms then resolve the resulting 3′ and 5′ flap structures, ultimately incorporating the newly synthesized DNA containing the desired edit into the genome [22].

Table 1: Core Components of the Prime Editing System

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| nCas9 (H840A) | CRISPR-Cas9 nickase mutant | Binds target DNA and nicks specific strand without creating double-strand break |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Typically M-MLV RT | Synthesizes DNA complementary to the RT template on the pegRNA |

| pegRNA | Engineered guide RNA with extensions | Specifies target site and templates desired genetic modification |

| PBS Sequence | Region of pegRNA | Anneals to nicked DNA strand to initiate reverse transcription |

| RT Template | Region of pegRNA encoding desired edit | Serves as template for DNA synthesis by reverse transcriptase |

Diagram 1: Prime editing molecular mechanism

Experimental Optimization and Validation

Efficiency Enhancement Strategies

Despite its precision, prime editing initially faced challenges with efficiency, prompting extensive optimization efforts. Recent approaches have focused on both the editing machinery and delivery methods. Systematic optimization has included structural and codon optimization of the nCas9-RT fusion enzyme, improvements to evade the mismatch repair pathway, and engineering more efficient pegRNAs [22]. Delivery method optimization has proven equally crucial, with the piggyBac transposon system emerging as an effective platform for stable genomic integration and sustained expression of prime editor components [22] [23]. This DNA-based transposition system facilitates gene transfer through a cut-and-paste mechanism, offering substantial cargo capacity (up to 20 kb) for multiplexed gene co-expression while circumventing immunogenicity concerns associated with viral delivery systems [22].

Combining these advancements has yielded remarkable improvements in editing efficiency. One comprehensive approach established single-cell clones with stable genomic integration of prime editors using piggyBac, utilized the CAG promoter for robust gene expression, and delivered engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) via lentivirus to ensure sustained expression for up to 14 days [22]. This integrated strategy achieved up to 80% editing efficiency across multiple cell lines and genomic loci, and demonstrated substantial efficiency (up to 50%) even in challenging human pluripotent stem cells in both primed and naïve states [22] [23].

Error Rate Reduction

Precision remains paramount in therapeutic genome editing. Recent research has addressed the error potential in prime editing, where the newly synthesized DNA flap must compete with the original DNA strand for incorporation into the genome [11]. If the original strand outcompetes the new one, the extra flap of new DNA may accidentally incorporate elsewhere, causing errors [11]. While early prime editors showed error rates ranging from approximately one error in seven edits to one in 121 edits for different editing modes, innovative protein engineering has dramatically improved fidelity [11].

MIT researchers developed modified Cas9 proteins with mutations that relax cutting constraints, making the original DNA strands less stable and more likely to be degraded [11]. This approach facilitates preferential incorporation of the new strands without introducing errors. By combining pairs of these mutations and incorporating them into a prime editing system with RNA binding proteins that stabilize the ends of the RNA template, researchers created a "vPE" editor that reduced error rates to just 1/60th of the original—ranging from one error in 101 edits to one in 543 edits across different editing modes [11].

Table 2: Prime Editing Efficiency and Error Rates Across Optimization Strategies

| Optimization Approach | Editing Efficiency | Error Rate | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PiggyBac + Lentiviral epegRNA | Up to 80% | Not specified | Multiple cell lines and genomic loci [22] |

| Stable Integration + CAG Promoter | Up to 50% | Not specified | Human pluripotent stem cells [22] |

| Original Prime Editor | Variable | 1:7 to 1:121 | Research settings [11] |

| vPE Editor | Maintained with improved precision | 1:101 to 1:543 | Mouse and human cells [11] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of prime editing requires carefully selected molecular tools and delivery systems. The following essential materials represent key components used in advanced prime editing experiments:

Prime Editor Plasmids: Engineered vectors such as pCMV-PE2 and pCMV-PEmax-P2A-hMLH1dn encode the fusion protein of nCas9 and reverse transcriptase [22] [23]. The PEmax variant represents a codon-optimized version with enhanced editing efficiency.

pegRNA Expression Systems: Specialized vectors (e.g., Lenti-TevopreQ1-Puro backbone) for cloning and expressing pegRNAs or epegRNAs (engineered pegRNAs) with structural modifications that improve stability and functionality [22] [23].

Delivery Vehicles:

- PiggyBac Transposon System: Comprises transposon plasmids with inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and a transposase helper plasmid (e.g., pCAG-hyPBase) for precise genomic integration of prime editing components through cut-and-paste mechanism [22].

- Lentiviral Vectors: Used for delivering pegRNAs to ensure sustained expression in target cells [22].

Reporter Constructs: Validation tools such as mCherry-STOP-GFP reporters, where GFP expression occurs only after successful readthrough of premature termination codons, enabling quantitative assessment of editing efficiency [13].

Selection Markers: Fluorescent proteins (mCherry) or antibiotic resistance genes (Puromycin) enable enrichment of successfully transfected or transduced cells [22].

Diagram 2: Prime editing optimization framework

Therapeutic Applications and Case Studies

The "search-and-replace" capability of prime editing enables innovative approaches for treating genetic disorders. A notable therapeutic strategy is Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough of Premature Termination Codons (PERT), which addresses nonsense mutations that account for approximately 24% of pathogenic alleles in the ClinVar database [13] [24]. Rather than correcting individual mutations, PERT uses prime editing to permanently convert a dispensable endogenous tRNA into an optimized suppressor tRNA (sup-tRNA) that enables readthrough of premature stop codons [13].

This approach was validated in human cell models of Batten disease (TPP1 p.L211X and p.L527X), Tay-Sachs disease (HEXA p.L273X and p.L274X), and Niemann-Pick disease type C1 (NPC1 p.Q421X and p.Y423X), where treatment with the same prime editor installing an optimized sup-tRNA restored 20-70% of normal enzyme activity [13]. In vivo delivery of a single prime editor that converts an endogenous mouse tRNA into a sup-tRNA extensively rescued disease pathology in a Hurler syndrome model (IDUA p.W392X), with approximately 6% IDUA enzyme activity restoration sufficient to nearly eliminate disease signs [13]. This disease-agnostic strategy demonstrates how a single editing agent could potentially treat diverse genetic disorders caused by premature stop codons, benefiting patient populations with conditions including cystic fibrosis, Stargardt disease, phenylketonuria, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy [24].

Prime editing's fundamental "search-and-replace" mechanism represents a paradigm shift in genome engineering, combining precise targeting with versatile editing capabilities. Through continued optimization of both the editing machinery and delivery systems, researchers have achieved substantial improvements in efficiency and fidelity. The technology's ability to perform precise genetic modifications without double-strand breaks positions it as a powerful tool for both basic research and therapeutic development. As optimization efforts continue and delivery challenges are addressed, prime editing holds exceptional promise for treating a broad spectrum of genetic disorders through both mutation-specific correction and disease-agnostic approaches, potentially enabling a single therapeutic agent to benefit diverse patient populations.

Methodology and Therapeutic Applications: From Pipeline to Patient

Prime editing represents a transformative leap in genome editing technology, enabling precise modifications without introducing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or requiring donor DNA templates [25] [1]. Developed in the lab of David Liu and first published in 2019, this "search-and-replace" editing system substantially expanded the scope of programmable genome editing beyond the capabilities of earlier technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases and base editors [26] [27]. The core innovation lies in fusing a catalytically impaired Cas9 nickase (nCas9) to a reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme, programmed with a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit [25]. This review traces the systematic evolution of the prime editing platform from its initial proof-of-concept (PE1) to the highly optimized and specialized systems in use today (PE7), detailing the technical improvements that have enhanced its efficiency, precision, and applicability for therapeutic development and basic research.

The Fundamental Mechanism of Prime Editing

The prime editing mechanism distinguishes itself from previous CRISPR-based systems by directly writing new genetic information from a pegRNA template into a specific DNA locus. Figure 1 illustrates the multi-step process that underpins all prime editor versions.

Figure 1. The Core Prime Editing Mechanism. The process begins when the prime editor protein (nCas9-Reverse Transcriptase fusion) bound to a pegRNA locates and nicks the target DNA. The exposed 3' end hybridizes with the pegRNA's Primer Binding Site (PBS), initiating reverse transcription from the Reverse Transcriptase Template (RTT) that encodes the desired edit. Cellular machinery then resolves the resulting DNA flaps, and mismatch repair incorporates the edit permanently [25] [3] [27].

This mechanism enables the installation of all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, with high precision and minimal indel byproducts [26] [1]. Its versatility and safety profile make it particularly promising for correcting pathogenic mutations in a research and therapeutic context.

The Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

The journey from PE1 to PE7 is a story of continuous optimization, addressing key challenges such as low editing efficiency, pegRNA stability, and unproductive cellular repair responses. The major versions of prime editors and their defining characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Evolution and Key Characteristics of Prime Editing Systems

| System | Core Components & Modifications | Key Innovation | Typical Editing Efficiency* | Primary Applications & Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 [25] [1] | Cas9 H840A nickase + wild-type M-MLV RT | Proof-of-concept system | ~10–20% | Established the search-and-replace mechanism. |

| PE2 [25] [1] | Cas9 H840A nickase + engineered M-MLV RT (5 mutations) | Enhanced reverse transcriptase efficiency | ~20–40% | Higher efficiency across diverse sites; foundation for subsequent systems. |

| PE3 [25] [1] | PE2 + additional nicking sgRNA (ngRNA) | Dual-nicking strategy to bias repair | ~30–50% | Increased editing efficiency by guiding heteroduplex resolution. |

| PE3b [26] | PE2 + ngRNA designed to bind only the edited strand | Strand-selective nicking to reduce indels | Similar to PE3, with 13-fold fewer indels | Improved product purity by minimizing unwanted indel formation. |

| PE4 [26] [1] | PE2 + co-expressed dominant-negative MLH1 (dnMLH1) | Transient inhibition of mismatch repair (MMR) | ~50–70% | Boosted efficiency in MMR-proficient cell lines. |

| PE5 [1] | PE3 + co-expressed dnMLH1 | Combines dual-nicking with MMR inhibition | ~60–80% | Maximizes efficiency for challenging edits by addressing two bottlenecks. |

| PE6a-g [26] [1] | Variants with compact RTs (e.g., PE6a, PE6b) or evolved M-MLV RT/Cas9 domains | Specialized editors for different edit types and improved delivery | ~70–90% | AAV-compatible systems (compact variants); tailored solutions for specific edits. |

| PEmax [26] | Codon-optimized RT, additional NLS, mutations in Cas9 | Optimized protein expression and nuclear localization | Higher than PE2 | A improved "architecture" used as the base for further advanced systems. |

| PE7 [26] [1] | PEmax + fusion to La protein (PE7) | Enhanced pegRNA stability by blocking exonuclease degradation | ~80–95% | Improved performance, especially in challenging cell types. |

*Reported editing efficiencies are approximate and based on performance in HEK293T cells, as indicated in [1]. Efficiency is highly dependent on the specific target locus, cell type, and edit type.

Foundational Systems: PE1 to PE3

The first-generation systems established and refined the core prime editing workflow. PE1 demonstrated the feasibility of the technology but with modest efficiency, achieving editing at levels of 0.7–5.5% for point mutations and 4–17% for small indels [25] [27]. The key breakthrough came with PE2, which incorporated an engineered M-MLV reverse transcriptase with five mutations (D200N, L603W, T330P, T306K, W313F) that enhanced its thermostability, processivity, and DNA-RNA affinity, leading to a 2.3- to 5.1-fold average increase in efficiency over PE1 [25] [26] [27].

Building on PE2, the PE3 system introduced a second sgRNA to nick the non-edited strand. This additional nick encourages the cell's repair machinery to use the edited strand as a template, thereby increasing the likelihood of permanently incorporating the desired change and boosting efficiency by a further 2-3 fold [25] [1] [27]. A refined version, PE3b, uses an ngRNA designed to bind only after the edit has been made to the target strand, reducing the potential for undesired indels by 13-fold compared to PE3 [26].

Addressing Cellular Repair: PE4 and PE5

A significant barrier to efficient prime editing is the cellular mismatch repair (MMR) system, which can recognize the heteroduplex DNA (containing one edited and one original strand) and revert the edit to the original sequence [26]. The PE4 and PE5 systems were developed to overcome this barrier.

Both systems co-express a dominant-negative version of the MLH1 protein (MLH1dn) to transiently inhibit the MMR pathway [26] [1]. PE4 combines this MMR suppression with the PE2 editor, while PE5 combines it with the PE3 system. This strategic inhibition gives the edited DNA strand a greater chance to be permanently established, improving editing efficiency by 7.7-fold in PE4 versus PE2 and 2.0-fold in PE5 versus PE3 [26] [1].

Specialization and Delivery Optimization: PE6 and PEmax

Further optimization led to the development of the PE6 series and the PEmax architecture. The PEmax system features a codon-optimized reverse transcriptase for human cells, additional nuclear localization signals, and beneficial mutations in the Cas9 domain, collectively improving protein expression and activity [26].

The PE6 system, built upon PEmax, represents a move toward specialization. It includes a suite of editors (PE6a-g) developed through phage-assisted evolution [26]. Some variants (PE6a, PE6b, PE6c) use compact reverse transcriptase domains from bacterial retrons or retrotransposons, reducing the overall size of the editor to facilitate packaging into delivery vehicles like adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) [26] [1]. Other PE6 variants (PE6e-g) contain mutations in the Cas9 domain that can be combined with the evolved RTs for additive improvements in efficiency for specific types of edits [26].

Enhancing RNA Stability: PE7

A common issue with earlier systems was the degradation of the 3' extension of the pegRNA, which contains the critical PBS and RTT sequences. The PE7 system addresses this by fusing the PEmax editor to the La protein, a ubiquitous eukaryotic RNA-binding protein that stabilizes pegRNAs by protecting them from exonuclease degradation [26] [1]. This innovation enhances pegRNA stability and further boosts editing efficiency without requiring changes to the pegRNA design itself.

Experimental Protocols for Prime Editing

A typical prime editing experiment involves the careful design of editing components, their delivery into cells, and the analysis of outcomes. The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing a PE3/PE5-type system in a mammalian cell line.

Component Design and Cloning

- pegRNA Design: The pegRNA must be designed to target the genomic locus and encode the desired edit. Tools like PrimeDesign (http://primedesign.pinellolab.org/) can automate this process, calculating parameters such as the PBS length (typically 10-15 nt) and RTT length (which includes the edit and necessary homology, often 25-40 nt) [28]. To enhance stability, engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) with 3' RNA pseudoknots can be used to prevent degradation [26].

- ngRNA Design: For PE3/PE5 systems, a nicking sgRNA (ngRNA) is designed to bind to the non-edited strand, approximately 50-100 bp away from the pegRNA nick site. The ngRNA should have a spacer sequence that matches the edited sequence to favor nicking only after successful editing (PE3b strategy) [26] [28].

- Plasmid Construction: The prime editor protein (e.g., PE2, PEmax) is typically encoded on one plasmid. The pegRNA and ngRNA are often cloned into separate expression plasmids under the control of U6 promoters [28]. The PE4/PE5 systems require an additional plasmid expressing the dominant-negative MLH1 [1].

Cell Transfection and Editing

- Cell Culture: HEK293T cells are a common model for initial testing. Cells are maintained in standard culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS) and seeded into multi-well plates 18-24 hours before transfection to reach 70-80% confluency [28].

- Transfection: A common transfection mix for a 96-well format includes 30 ng of PE2/PE5max plasmid, 10 ng of pegRNA plasmid, and 3.3 ng of ngRNA plasmid, using a transfection reagent like TransIT-X2 [28]. For PE4/PE5, the MLH1dn plasmid must be included. The optimal ratio may require empirical adjustment for different cell lines or edits.

- Incubation: Cells are analyzed 72 hours post-transfection to allow sufficient time for editing and protein turnover [28].

Analysis of Editing Outcomes

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Cells are lysed, and genomic DNA is extracted using a commercial kit or a simple proteinase K-based lysis buffer [28].

- Amplicon Sequencing: The target locus is amplified by PCR, and the products are subjected to next-generation sequencing (NGS). This is the gold standard for quantifying prime editing efficiency and byproducts.

- Efficiency Calculation: NGS data is processed using computational pipelines (e.g., CRISPResso2) to calculate the percentage of reads containing the desired edit, as well as the rates of indels and other unintended modifications [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Prime Editing Research

Successful implementation of prime editing requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key resources for researchers.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Prime Editing

| Item | Function & Importance | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Plasmids | Expresses the fusion protein (nCas9-RT). The backbone for all editing activity. | - PE2/pJUL2440: A common PE2 construct with a P2A-eGFP reporter [28].- PEmax: An optimized backbone with improved expression [26]. |

| pegRNA Cloning Vectors | Allows for the expression of the complex pegRNA, which includes the spacer, scaffold, PBS, and RTT. | - pUC19-hU6-pegRNA-gg-acceptor: A common entry vector for pegRNA cloning (Addgene #132777) [28]. |

| ngRNA Cloning Vectors | For expressing the nicking sgRNA in PE3/PE5 systems. | - Standard U6-sgRNA expression vectors (e.g., Addgene #65777) [28]. |

| MMR Inhibition Plasmid | Expresses the dominant-negative MLH1dn protein to transiently suppress mismatch repair and boost efficiency. | - Required for the PE4 and PE5 systems [26] [1]. |

| Design Software | Critical for designing effective pegRNAs and ngRNAs by automating parameter optimization. | - PrimeDesign: A user-friendly web and command-line tool for designing single and pooled pegRNAs [28].- PrimeVar: A database of pre-designed pegRNAs for pathogenic ClinVar variants [28]. |

| Delivery Tools | Methods to introduce prime editing components into cells. | - Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): For non-viral delivery of RNP or mRNA [3].- Engineered Virus-Like Particles (eVLPs): For in vivo delivery with improved efficiency and safety [7].- Viral Vectors (AAV, Lentivirus): AAV is suited for in vivo delivery but has limited cargo capacity, favoring compact editors like PE6a-c [26] [1]. |

The evolution from PE1 to PE7 demonstrates a remarkable trajectory of scientific problem-solving, driven by a deep understanding of the biochemical and cellular barriers to precise genome editing. Each generation has systematically addressed a key limitation: reverse transcriptase efficiency (PE2), heteroduplex resolution (PE3), mismatch repair (PE4/PE5), editor size and specialization (PE6), and guide RNA stability (PE7). This continuous refinement has transformed prime editing from a novel proof-of-concept into a powerful and precise platform capable of correcting a vast majority of known pathogenic genetic variants [25] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this expanding toolkit offers increasingly sophisticated and viable strategies to target the genetic root causes of diseases, paving the way for a new generation of therapeutic interventions.

This technical guide details the application of prime editing (PE) to correct disease-causing mutations in live animal models, situating these advances within the broader research on how prime editing works. It provides an in-depth analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, focusing on experimental outcomes, detailed methodologies, and key reagents.

Quantitative Analysis of In Vivo Prime Editing Outcomes

The following tables summarize key quantitative data from recent pioneering in vivo prime editing studies, providing a benchmark for editing efficiency and functional recovery.

Table 1: Prime Editing Efficiency in the TIGER Mouse Model Across Tissues [29]

| Tissue / Cell Type | Delivery Method | Editor | Editing Efficiency (%) | Readout Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal Pigment Epithelium | AAV | ABE / PE | Quantified via fluorescence restoration | In vivo & ex vivo confocal microscopy |

| Photoreceptors | AAV | ABE / PE | Quantified via fluorescence restoration | In vivo & ex vivo confocal microscopy |

| Müller Glia | AAV | ABE / PE | Quantified via fluorescence restoration | In vivo & ex vivo confocal microscopy |

| Trabecular Meshwork | AAV | ABE / PE | Quantified via fluorescence restoration | In vivo & ex vivo confocal microscopy |

| Hepatocytes | AAV (Intravenous) | PE | Quantified via fluorescence restoration | Confocal microscopy |

| Skeletal Muscle | AAV (Intravenous) | PE | Quantified via fluorescence restoration | Confocal microscopy |

| Brain Neurons | AAV (Intravenous) | PE | Quantified via fluorescence restoration | Confocal microscopy |

Table 2: Functional Rescue in Disease Models via the PERT Strategy [13] [12]

| Disease Model | Targeted Gene / Mutation | System | Functional Rescue | Pathology Rescue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurler Syndrome | IDUA p.W392X | Mouse Model | ~6% of normal IDUA enzyme activity | Nearly complete rescue of disease pathology |

| Batten Disease | TPP1 p.L211X, p.L527X | Human Cell Model | 20-70% of normal enzyme activity | N/D |

| Tay-Sachs Disease | HEXA p.L273X, p.L274X | Human Cell Model | 20-70% of normal enzyme activity | N/D |

| Niemann-Pick C1 | NPC1 p.Q421X, p.Y423X | Human Cell Model | 20-70% of normal enzyme activity | N/D |

| General Reporter | GFP nonsense mutation | Mouse Model | ~25% production of full-length GFP protein | N/A |

Experimental Protocols for Key In Vivo Studies

Protocol: Prime Editing in the TIGER Reporter Mouse

The TdTomato In Vivo Genome-Editing Reporter (TIGER) mouse model provides a versatile system for assessing prime editing delivery and efficiency across tissues with single-cell resolution [29].

- Animal Model: The TIGER mouse carries a constitutively expressed, mutated tdTomato gene (Q115X, Q357X) integrated into the Polr2a locus, abolishing fluorescence. Successful adenine base editing (ABE) or prime editing (PE) reverts the nonsense mutations and restores tdTomato fluorescence [29].

- Editor Delivery: Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors are packaged with the prime editing machinery and administered via local (e.g., intravitreal injection for ocular tissues) or systemic (intravenous injection) routes [29].

- Prime Editor Construct: The construct typically uses a PE2 system, which consists of a Cas9 nickase (H840A)-reverse transcriptase fusion protein and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). For the TIGER model, pegRNAs were designed to correct Q115X or Q357X mutations using the PE2 approach without an additional nicking sgRNA [29].

- In Vivo Imaging and Analysis: Editing is quantified days to weeks post-injection using in vivo and ex vivo two-photon confocal microscopy to detect restored tdTomato fluorescence. Tissues can be processed for next-generation sequencing (NGS) to determine precise editing rates and indel frequencies [29].

Protocol: Disease-Agnostic Therapy with PERT

The Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough of Premature Termination Codons (PERT) strategy installs a suppressor tRNA (sup-tRNA) to read through nonsense mutations, offering a single therapeutic for multiple diseases [13] [12].

- sup-tRNA Engineering: A comprehensive screen of tens of thousands of variants of all 418 human tRNAs was conducted to identify sequences with high suppression potency. The optimized sup-tRNA was designed for the amber stop codon (TAG) [13].

- Genomic Installation via Prime Editing: A prime editor is programmed to permanently convert a single, dispensable endogenous tRNA gene (e.g., tRNA-Gln-CTG-6-1 or tRNA-Arg-CCG-2-1) into the optimized sup-tRNA. This avoids overexpression and preserves native regulation [13].

- In Vivo Validation:

- Reporter Mice: Mice are co-delivered with a reporter construct (e.g., GFP with a nonsense mutation) and the PERT editor. Successful editing is indicated by GFP expression [13].

- Disease Model (Hurler Syndrome): An IDUA p.W392X mouse model is treated systemically with the PERT editor. Functional rescue is assessed by measuring IDUA enzyme activity in tissues (e.g., brain, liver, spleen) and evaluating the amelioration of disease pathology [13] [12].

- Safety Profiling: Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and transcriptomic/proteomic analyses are performed to assess off-target editing and global impacts on gene expression [13].

Visualizing Prime Editing Workflows and Strategies

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanisms and experimental workflows for the in vivo success stories discussed.

Prime Editing Mechanism and PERT Strategy

Diagram 1: Core PE mechanism and the disease-agnostic PERT strategy. The standard prime editing process (solid path) leads to direct gene correction. The PERT strategy (dashed path) installs a sup-tRNA that enables readthrough of premature termination codons (PTCs) systemically [13] [12].

TIGER Mouse Model Workflow

Diagram 2: The TIGER mouse model workflow for assessing prime editing delivery. The model starts with a non-fluorescent mutant reporter. After AAV-delivered prime editing, successful correction is directly quantified by restored red fluorescence and NGS [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table catalogs essential materials and their functions, as used in the featured in vivo studies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for In Vivo Prime Editing Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TIGER Mouse Model | In vivo reporter for quantifying editing delivery and efficiency with single-cell resolution across tissues [29]. | Benchmarking AAV capsids or LNP formulations for organ-targeted delivery [29]. |

| PERT Prime Editor | A specific prime editing system designed to install an optimized suppressor tRNA at an endogenous genomic locus [13] [12]. | Developing disease-agnostic therapies for nonsense mutations in models of Hurler syndrome, Batten disease, etc. [13] [12]. |

| EnginepegRNAs (epegRNAs) | pegRNAs with 3' structural motifs (e.g., tevopreQ1) that enhance RNA stability and increase editing efficiency [17]. | Used in high-efficiency editing platforms in cell lines and animal models to achieve >90% precise editing [17]. |

| AAV Vectors | Viral delivery vehicle for in vivo transport of genome editing components. Can be serotyped for tissue tropism [29] [30]. | Delivering prime editors to the mouse eye, liver, muscle, and brain [29]. |

| MLH1-Deficient Cell Lines | Mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient cells (e.g., PEmaxKO) that prevent correction of prime edits, dramatically boosting efficiency [17] [6]. | Initial screening and optimization of pegRNAs prior to in vivo testing [17]. |

| Computational Design Tools (e.g., PRIDICT) | Machine learning models that predict pegRNA efficiency, guiding optimal pegRNA design for a given target sequence [31]. | Pre-screening pegRNA designs in silico to select the most promising candidates for experimental validation [31]. |

The development of personalized genetic medicines faces a fundamental scalability problem: creating a unique therapeutic agent for each of the thousands of known pathogenic mutations is economically and logistically challenging [13] [12]. Among the more than 200,000 disease-causing mutations documented in the ClinVar database, approximately 24% are nonsense mutations [13] [12] [32]. These mutations introduce a premature termination codon (PTC) within the coding sequence of an mRNA transcript, leading to truncated, non-functional proteins that underlie diverse genetic disorders [13] [33]. Until recently, therapeutic strategies required developing distinct genome-editing treatments for each specific nonsense mutation, significantly limiting the practical application of gene-editing technologies for rare diseases [12].

The Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough of Premature Termination Codons (PERT) strategy represents a paradigm shift from this mutation-specific approach. Developed by researchers at the Broad Institute, PERT leverages the versatility of prime editing to install a universal suppressor tRNA (sup-tRNA) that enables cells to read through PTCs regardless of their genomic context [13] [12]. This disease-agnostic platform has the potential to treat multiple unrelated genetic conditions with a single therapeutic agent, substantially expanding the population that could benefit from a single gene-editing drug [32]. By addressing a common molecular pathology across diverse diseases, PERT circumvents the need to invest multiple years and millions of dollars developing individual treatments for each genetic variant [12].

Technical Foundation: Prime Editing and Suppressor tRNAs

Prime Editing Architecture and Mechanism