Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): A Comprehensive Guide for CRISPR Researchers and Therapists

This article provides a definitive guide to the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) for researchers and drug development professionals working with CRISPR technology.

Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): A Comprehensive Guide for CRISPR Researchers and Therapists

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide to the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) for researchers and drug development professionals working with CRISPR technology. It covers the foundational biology of PAMs, including their critical role in self vs. non-self discrimination in bacterial adaptive immunity. The content details methodological approaches for PAM identification and its application in guide RNA design, alongside strategies for overcoming PAM limitations through engineered Cas variants and alternative nucleases. Finally, it examines validation techniques for assessing PAM specificity and the comparative analysis of different CRISPR systems, directly addressing the needs of scientists optimizing gene editing experiments and developing therapeutic applications.

What is a PAM? Unraveling the Core Concept of CRISPR Recognition

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence that is absolutely required for the function of many CRISPR-Cas systems, serving as a fundamental recognition signal for distinguishing between self and non-self DNA [1] [2]. In the context of bacterial adaptive immunity, the PAM is a component of the invading viral or plasmid DNA (the protospacer) but is not present in the bacterial host's own CRISPR locus [1]. This critical distinction prevents the CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease from targeting and destroying the bacterial genome itself [1] [3]. The PAM is typically located immediately adjacent to the DNA sequence targeted by the Cas nuclease—the protospacer—with its exact position (either upstream or downstream) varying depending on the specific Cas protein and CRISPR system type [2]. For the most widely used CRISPR system, Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the canonical PAM is the sequence 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleobase, and it is found directly downstream (on the 3' end) of the target DNA sequence [1] [4] [3]. The PAM is not part of the guide RNA sequence and must be present in the genomic DNA being targeted for successful cleavage to occur [4] [3].

PAM Sequences and Their Diversity Across CRISPR Systems

The sequence and location of the PAM are not universal; they vary significantly across different CRISPR-Cas systems and the bacterial species from which they are derived [1] [3]. This diversity reflects the adaptation of various CRISPR systems to recognize different viral invaders. The PAM's location relative to the protospacer is a key differentiating factor: in Class 2, Type II systems (which include Cas9), the PAM is typically found at the 3' end of the protospacer, whereas in Class 1, Type I and Class 2, Type V systems, it is usually located at the 5' end [2]. The length of the PAM sequence also varies, generally ranging from 2 to 6 base pairs [1] [3].

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Common and Engineered CRISPR Nucleases

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism of Origin | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Location Relative to Protospacer |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG [1] [3] | 3' end [2] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRR(T/N) [3] | 3' end |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT [3] | 3' end |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC [3] | 3' end |

| LbCas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV [3] | 5' end [2] |

| AsCas12a (Cpf1) | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV [3] | 5' end [2] |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN [3] | 5' end |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered (from Cas12i) | TN and/or TNN [3] | 5' end |

| Engineered SpCas9 | Engineered (from S. pyogenes) | NGA (highly efficient non-canonical) [1] | 3' end |

Beyond the canonical SpCas9 PAM, other naturally occurring nucleases offer alternative targeting ranges. For instance, the Cas9 from Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9) recognizes the longer, more specific PAM NNGRR(T/N), which can be advantageous for reducing off-target effects but limits the number of possible target sites in a genome [3]. Conversely, nucleases from the Cas12a (Cpf1) family recognize a TTTV PAM (where "V" is A, C, or G), which is rich in thymine and located at the 5' end of the protospacer, a fundamental structural and functional difference from Cas9 systems [1] [3]. Research has also shown that 5'-NGA-3' can function as a highly efficient non-canonical PAM for SpCas9 in human cells, though its efficiency varies depending on the genomic location [1].

PAM Function: The Molecular Mechanism of Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination

The PAM serves two critical, interconnected functions in CRISPR biology: enabling DNA interrogation and providing self versus non-self discrimination.

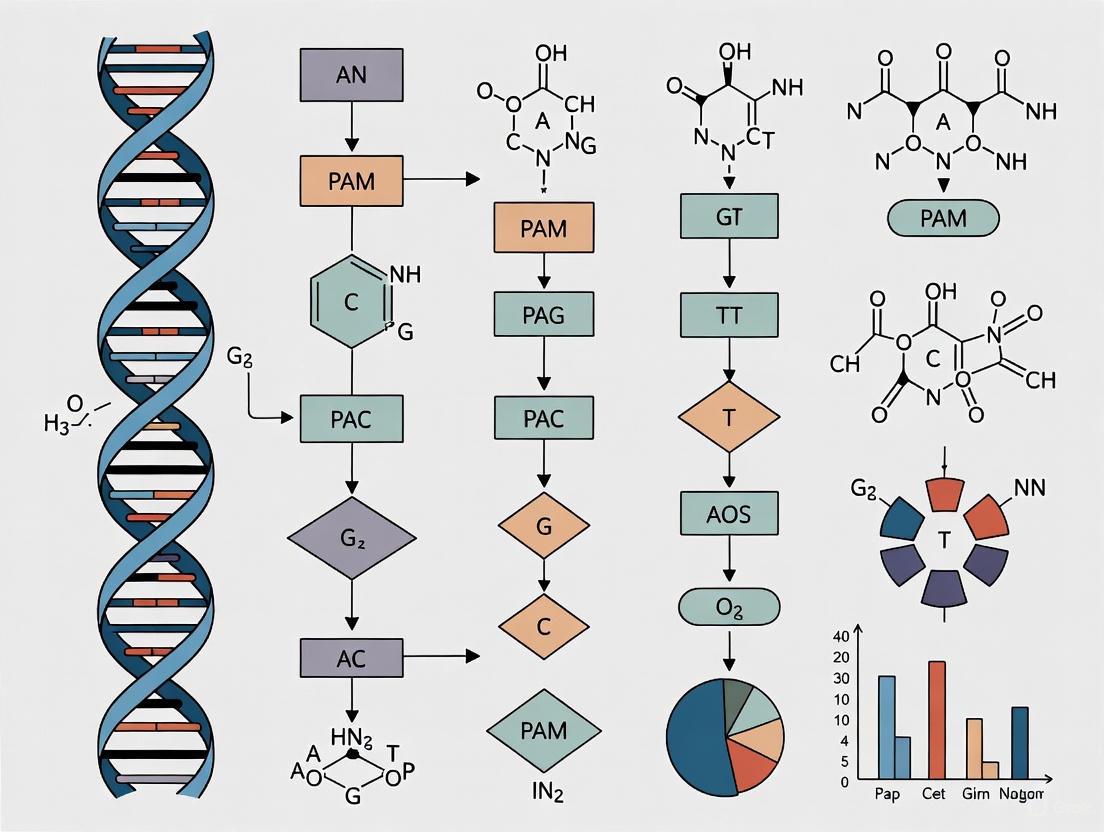

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of PAM-dependent self versus non-self discrimination in a Type II CRISPR-Cas system.

Enabling DNA Interrogation and Cleavage

The Cas nuclease first scans the DNA for the presence of its cognate PAM sequence [3]. Recognition of the PAM by the Cas protein is thought to destabilize the adjacent DNA duplex, facilitating the unwinding of the DNA and allowing the guide RNA (gRNA) to "interrogate" the sequence by attempting to base-pair with it [4]. If the gRNA sequence is fully complementary to the DNA sequence immediately upstream of the PAM, the Cas nuclease becomes activated and introduces a double-strand break in the DNA [1] [5] [3]. For SpCas9, this cut is typically made 3 to 4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM [3].

Discriminating Between Self and Non-Self

This is the primary biological role of the PAM. When a bacterium incorporates a fragment of viral DNA (a protospacer) into its own CRISPR locus as a spacer for immunological memory, it integrates only the protospacer sequence and excludes the PAM [1] [3]. Consequently, when the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) is transcribed and guides the Cas nuclease to search the bacterial genome, the genomic CRISPR locus itself lacks the required PAM sequence adjacent to the spacer. Even though the gRNA finds a perfect complementary match in the CRISPR array, the absence of the PAM prevents the Cas nuclease from cleaving the bacterium's own DNA, thus preventing autoimmunity [1] [2] [3].

Experimental Protocols: Identifying and Evaluating PAM Specificity

Determining the PAM specificity of a novel Cas nuclease and assessing the off-target effects of engineered nucleases are critical steps in CRISPR tool development.

Protocol for PAM Identification (PAM-SCAN Assay)

This protocol is used to empirically determine the PAM requirements for an uncharacterized Cas nuclease.

- Library Construction: Synthesize a randomized oligonucleotide library where a region of potential protospacer sequence is flanked by a fixed, known sequence on one side and a fully randomized (e.g., NNNN) sequence on the other. This randomized region serves as the potential PAM pool [2].

- In Vitro Cleavage: Incubate the oligonucleotide library with the purified Cas nuclease and its corresponding guide RNA, which is complementary to the fixed protospacer sequence.

- Selection of Cleaved Products: The nuclease will only cleave those library members that contain a functional PAM sequence adjacent to the protospacer. Isolate the cleaved DNA fragments using gel extraction or size-selection methods.

- Amplification and Sequencing: Amplify the selected cleaved fragments using PCR and subject them to high-throughput sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Align the sequences of the cleaved fragments to identify the conserved nucleotides immediately adjacent to the protospacer. This consensus sequence defines the nuclease's PAM requirement [2].

Protocol for Assessing Off-Target Effects (GUIDE-Seq)

GUIDE-Seq (Genome-wide Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing) is a powerful method to profile off-target cleavages of CRISPR nucleases genome-wide, which is crucial for assessing the specificity of nucleases with engineered PAM recognition [1] [6].

- Transfection: Co-transfect cells with three components:

- A plasmid expressing the Cas nuclease and the gRNA of interest.

- An oligonucleotide duplex (the "GUIDE-Seq tag").

- A transfection control plasmid.

- Tag Integration: When the Cas nuclease creates a double-strand break (whether on-target or off-target), the oligonucleotide tag is integrated into the break site via the cell's endogenous DNA repair machinery.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Shearing: Harvest cells 2-3 days post-transfection, extract genomic DNA, and fragment it by sonication or enzymatic digestion.

- Enrichment and Library Preparation: Use PCR to enrich for genomic DNA fragments that contain the integrated tag. Then, prepare a sequencing library from these enriched fragments.

- High-Throughput Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the library and use bioinformatic pipelines to map the sequencing reads back to the reference genome. The locations where the tag has been integrated represent bona fide nuclease cleavage sites, providing a genome-wide profile of off-target activity [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PAM Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PAM-Focused CRISPR Experiments

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application in PAM Research |

|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease Variants (SpCas9, SaCas9, Cas12a, etc.) | The core enzymes for CRISPR editing; comparing different variants allows researchers to leverage diverse PAM specificities for different target loci [3]. |

| Engineered Cas Variants (e.g., SpCas9-NG, xCas9) | Cas proteins engineered via directed evolution to recognize alternative, often relaxed, PAM sequences (e.g., NG, GAA), expanding the range of targetable genomic sites [1] [3]. |

| PAM Library Oligonucleotides | Synthetic double-stranded DNA libraries with randomized PAM regions, essential for empirical determination of novel nuclease PAM specificity (e.g., in PAM-SCAN assays) [2]. |

| GUIDE-Seq Oligonucleotide Duplex | A short, double-stranded oligonucleotide that is incorporated into CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks, enabling unbiased, genome-wide identification of off-target cleavage sites [1] [6]. |

| Single Guide RNA (sgRNA) | The synthetic RNA molecule that complexes with the Cas nuclease and directs it to a specific DNA sequence adjacent to a compatible PAM; the design excludes the PAM sequence itself [1] [3]. |

| Homing Guide RNA (hgRNA) | A specialized guide RNA that includes the PAM sequence within its targeting domain, enabling it to target its own DNA locus for self-cleavage. Used in cellular barcoding and lineage tracing studies [3]. |

| PAMmer Oligonucleotide | A specially designed DNA oligonucleotide that provides a PAM sequence in trans. This allows Cas9, which normally only targets DNA, to bind and cleave single-stranded RNA targets [2]. |

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif is a simple yet powerful DNA signature that lies at the very heart of CRISPR-Cas function. Its role in enabling pathogen discrimination in bacteria has made it an indispensable component of modern genome engineering. The location and sequence of the PAM directly determine the targetable genomic space for any given CRISPR system. While the natural diversity of Cas nucleases provides a range of PAM options, the field is increasingly relying on protein engineering to overcome PAM limitations. Through directed evolution and structure-guided design, researchers have successfully created novel Cas9 variants like SpCas9-NG with altered PAM specificities, expanding the toolbox for precise genome manipulation [1] [3]. Future research will continue to focus on discovering novel nucleases with unique PAM preferences and further engineering existing ones to achieve the ultimate goal of unrestricted targeting of any DNA sequence, a critical step for advancing both basic research and therapeutic applications of CRISPR technology.

The Fundamental Role in Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination

Within adaptive immune systems of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the discrimination of self from non-self represents a foundational biological imperative. In CRISPR-Cas systems, this discrimination is mechanistically enabled by the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short, conserved DNA sequence adjacent to target sites in foreign genetic material. This whitepaper delineates the molecular mechanisms of PAM function, details advanced methodologies for its characterization, and synthesizes quantitative data on PAM diversity. Framed within contemporary PAM research, this analysis underscores how understanding this motif is accelerating the development of precision genome-editing tools and therapeutic applications, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a technical guide to the core principles and experimental approaches defining the field.

The ability to distinguish between self and non-self is a fundamental requirement for maintaining organismal integrity. In vertebrate immunology, this process involves complex cellular mechanisms to avoid autoimmune reactions while effectively targeting pathogens [7]. In prokaryotes, the CRISPR-Cas system provides an adaptive immune defense that executes this discrimination with remarkable precision [8].

The CRISPR-Cas system protects bacteria and archaea from invading viruses and plasmids by incorporating short sequences from the invader's genome (protospacers) into the host's CRISPR locus. These stored sequences are later transcribed into guide RNAs that direct Cas nucleases to cleave matching foreign DNA upon re-infection [2]. A critical problem arises: how does the nuclease distinguish between the foreign DNA target (a protospacer) and the identical sequence stored within the host's own CRISPR locus? The solution lies in the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [2] [8].

The PAM is a short, specific nucleotide sequence (typically 2-6 bp) that flanks the target DNA sequence (protospacer) in the invading genome. Cas nucleases are engineered to recognize this motif; its presence licenses cleavage, while its absence from the host's CRISPR array prevents autoimmunity [4]. Thus, the PAM serves as the definitive molecular signature of "non-self," establishing a simple yet elegant mechanism for immune discrimination that parallels central tolerance in vertebrate adaptive immunity [9].

Molecular Mechanisms of PAM-Dependent Discrimination

PAM as the Molecular Signature of Non-Self

The PAM enables self/non-self discrimination through spatial separation from the integrated spacer. During spacer acquisition, the Cas1-Cas2 complex recognizes a PAM sequence in the foreign DNA and excises a protospacer fragment immediately adjacent to it. This PAM is not integrated into the CRISPR array, meaning the host's stored immune memory lacks this critical recognition signal [2]. During interference, the Cas effector complex (e.g., Cas9) requires the presence of the same PAM sequence adjacent to the DNA target to initiate cleavage. The host's CRISPR loci, lacking PAM sequences next to the spacers, are thus immunologically silent [8]. This mechanism ensures that the immune response is mounted only against foreign invaders while protecting the host's genomic integrity.

Structural Basis of PAM Recognition

PAM recognition occurs through specific protein domains within Cas effectors that interact with the DNA minor groove. Structural analyses reveal that different Cas proteins have evolved distinct PAM-interacting domains:

- Cas9 (Type II systems): For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), a positively charged arginine-rich region between the PAM-interacting (PI) and WED domains recognizes the 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence located 3' of the protospacer [10] [8]. Recognition involves specific hydrogen bonding and structural rearrangements that license DNA cleavage.

- Cas12 (Type V systems): Cas12a effectors recognize T-rich PAMs (e.g., TTTN) located 5' of the protospacer through a distinct mechanism involving a conserved lysine residue that interacts with the nucleotide base [11] [8].

- Type I Systems: These multi-subunit complexes recognize PAMs through the Cascade complex, with the CasA subunit playing a key role in PAM binding [8].

The PAM interaction initiates local DNA melting, creating an R-loop that enables crRNA-DNA hybridization and subsequent cleavage activity [8]. This multi-step verification process ensures high-fidelity target recognition.

Figure 1: PAM-Mediated Self/Non-Self Discrimination Pathway. The presence of a PAM sequence licenses the CRISPR-Cas system for target recognition and cleavage of non-self DNA. The host CRISPR locus lacks adjacent PAM sequences, preventing autoimmune self-targeting.

Advanced Methodologies for PAM Determination

Traditional PAM identification relied on in silico analyses of protospacer conservation [8]. Contemporary methods employ high-throughput experimental approaches to comprehensively define PAM recognition profiles with nucleotide resolution.

PAM-READID: A Mammalian Cell-Based Determination Method

The recently developed PAM-readID (PAM REcognition-profile-determining Achieved by Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides Integration in DNA double-stranded breaks) method enables rapid, simple, and accurate PAM determination in mammalian cells [12]. This method addresses critical limitations of earlier approaches that depended on fluorescent reporters and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), which were technically complex and not readily amenable to broad adoption [12].

Figure 2: PAM-readID Experimental Workflow. This method leverages dsODN integration to tag cleaved DNA ends bearing functional PAM sequences, enabling their selective amplification and sequencing.

Detailed PAM-readID Protocol

- Library Construction: Generate a plasmid library containing a fixed target sequence flanked by fully randomized nucleotide regions (e.g., 6N) at the PAM position [12].

- Mammalian Cell Transfection: Co-transfect the PAM library plasmid with plasmids expressing the Cas nuclease and its corresponding sgRNA, along with double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODN) into mammalian cells [12].

- Cleavage and Integration: After 72 hours, the Cas nuclease cleaves target sites bearing functional PAMs. Cellular non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair mechanisms integrate the dsODN into the cleavage site, tagging functional PAM sequences [12].

- Selective Amplification: Extract genomic DNA and amplify integrated sequences using a primer specific to the dsODN tag and a second primer specific to the target plasmid [12].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Subject amplicons to high-throughput sequencing (HTS) or Sanger sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis of recovered sequences reveals the PAM recognition profile [12].

PAM-readID has successfully determined PAM profiles for SaCas9, SaHyCas9, Nme1Cas9, SpCas9, SpG, SpRY, and AsCas12a in mammalian cells, demonstrating its broad applicability [12]. The method's sensitivity allows for PAM determination with as few as 500 HTS reads for SpCas9, and Sanger sequencing can provide a cost-effective alternative for Cas9 PAM profiling [12].

Alternative PAM Determination Methods

- In Vitro Cleavage Assays: Utilize purified Cas effector complexes to cleave DNA libraries containing randomized PAM regions, followed by sequencing of cleavage products to identify functional PAMs [8].

- Bacterial Plasmid Depletion Assays: Transform plasmids containing randomized PAM libraries into bacteria expressing CRISPR-Cas systems. Functional PAMs lead to plasmid cleavage and depletion, which can be quantified by sequencing the remaining plasmid pool [8].

- PAM-SCANR (PAM Screen Achieved by NOT-gate Repression): Employs catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) to repress a GFP reporter when binding to functional PAMs. FACS sorting, plasmid recovery, and sequencing identify functional PAM motifs [8].

Quantitative PAM Profiling Data and Nuclease Engineering

PAM Diversity Across CRISPR-Cas Systems

Comprehensive PAM profiling has revealed substantial diversity in sequence requirements across different Cas nucleases, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: PAM Sequences of Commonly Used and Engineered Cas Nucleases

| Cas Nuclease | Organism/Source | PAM Sequence (5'→3') | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | Canonical wild-type; most extensively characterized | [3] [4] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT | Shorter PAM expands targetable genome space | [3] [11] |

| Nme1Cas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | Longer PAM may enhance specificity | [3] |

| AsCas12a | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTN | Also known as Cpf1; creates staggered cuts | [12] [11] |

| LbCas12a | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTN | Engineered Ultra variant recognizes TTTN | [11] |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC | Compact size advantageous for delivery | [3] |

| xCas9 | Engineered from SpCas9 | NG, GAA, GAT | Broad PAM recognition through directed evolution | [10] |

| SpRY | Engineered from SpCas9 | NRN > NYN | Near PAM-less variant; greatly expanded targeting | [12] |

N = A, C, G, or T; R = A or G; V = A, C, or G; Y = C or T

Engineering Cas Nucleases with Altered PAM Specificities

Protein engineering has created Cas variants with altered PAM specificities to expand targeting capabilities:

- xCas9: An evolved SpCas9 variant with mutations that introduce flexibility in the R1335 residue, enabling recognition of alternative PAM sequences (NG, GAA, GAT) while maintaining high specificity [10]. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that increased side-chain flexibility confers entropic preference that broadens PAM recognition [10].

- SpG and SpRY: Engineered SpCas9 variants with progressively relaxed PAM requirements. SpG recognizes NG PAMs, while SpRY recognizes NRN (preferentially) and NYN PAMs, approaching PAM-independent targeting [12].

- Cas12a Ultra: Engineered AsCas12a variant with enhanced on-target potency and expanded PAM recognition (TTTN in addition to TTTV), increasing target range for genome editing [11].

These engineered nucleases significantly expand the targetable genomic space, enabling precise editing at sites previously inaccessible to CRISPR systems.

Research Reagent Solutions for PAM Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PAM Determination Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in PAM Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease Kits | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9, Alt-R Cas12a (Cpf1) Ultra | Engineered nucleases with defined PAM specificities for screening or validation |

| PAM Library Constructs | Randomized PAM plasmids (e.g., 6N libraries) | Substrate for determining nuclease PAM recognition profiles |

| dsODN Integration Tags | GUIDE-seq dsODN (modified for PAM-readID) | Tags Cas cleavage sites in mammalian cells for functional PAM identification |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | HTS platforms (Illumina, PacBio) | High-throughput sequencing of amplified PAM regions for comprehensive profiling |

| Cell Sorting Systems | FACS instrumentation | Enrichment of cells with functional PAM interactions (for reporter-based methods) |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CRISPResso2, PAM Wheel visualization | Analysis of HTS data and visualization of PAM enrichment profiles |

Applications and Future Directions in PAM Research

The precise understanding of PAM biology has catalyzed advances across multiple domains:

- Therapeutic Genome Editing: Engineered nucleases with relaxed PAM constraints enable targeting of previously inaccessible disease-associated mutations. For example, SpRY's near-PAM-less activity expands potential therapeutic targets for genetic disorders [12].

- Diagnostic Technologies: PAM requirements inform the design of CRISPR-based diagnostic platforms (e.g., SHERLOCK, DETECTR), where PAM compatibility between Cas effectors and target sequences must be optimized for detection sensitivity [8].

- Microbiome Engineering: The diversity of natural PAM preferences across Cas orthologs enables simultaneous multiplexed editing without cross-talk, facilitating complex microbial community engineering [11].

- Synthetic Biology: PAM-based self/non-self discrimination principles are being incorporated into synthetic genetic circuits to create cellular computation systems with controlled memory and targeting capabilities.

Future research directions include developing comprehensive PAM prediction algorithms, engineering completely PAM-independent nucleases without compromised fidelity, and elucidating the evolutionary dynamics between PAM requirements and viral anti-CRISPR strategies.

The protospacer adjacent motif represents a elegant evolutionary solution to the fundamental biological challenge of self/non-self discrimination. Through its specific recognition by Cas effector complexes, the PAM licenses destructive activity against foreign genetic elements while protecting host genomes. Contemporary research has progressed from foundational mechanistic understanding to sophisticated engineering of PAM interactions, dramatically expanding the targeting scope of CRISPR technologies. As PAM determination methods like PAM-readID continue to evolve, and as engineered nucleases with novel PAM specificities emerge, the potential for basic research and therapeutic applications will continue to grow. The ongoing investigation of PAM biology stands as a testament to how deciphering nature's molecular discrimination strategies can power transformative technological advances.

PAM Sequences Across Different CRISPR-Cas Systems (Type I, II, V)

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs in length) that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by CRISPR-Cas systems [3]. This motif serves as an essential recognition signal for Cas nucleases, enabling them to identify foreign genetic material while avoiding self-destructive targeting of the bacterial genome [3] [8]. The PAM sequence is typically located 3-4 nucleotides downstream from the Cas nuclease cut site and is required for the CRISPR system to distinguish between "self" (the bacterium's own DNA) and "non-self" (invading viral or plasmid DNA) [3].

The fundamental role of PAM sequences extends across all major CRISPR-Cas systems, though the specific sequences and recognition mechanisms vary substantially between different types and subtypes [8]. In natural bacterial immunity, PAM sequences prevent autoimmunity by ensuring that Cas nucleases do not target the host's own CRISPR arrays, which lack these adjacent motifs [13]. For genome engineering applications, the PAM requirement represents both a targeting constraint and a specificity safeguard, as Cas nucleases will only cleave DNA sequences that are both complementary to the guide RNA and adjacent to an appropriate PAM [3] [14].

PAM Recognition Across Major CRISPR-Cas Systems

Type I Systems

Type I CRISPR-Cas systems employ multi-protein effector complexes (Class 1) for target interference and exhibit distinct PAM recognition patterns. Research on the Escherichia coli Type I-E system has revealed a complex PAM recognition profile with clear functional separation among different trinucleotide sequences [13].

Experimental analysis of all 64 possible trinucleotide PAM combinations demonstrated that they separate into three distinct functional categories: non-functional PAMs that cannot support interference, rapid-interference PAMs that support fast target degradation, and attenuated PAMs that support intermediate, delayed interference [13]. Specifically, 36 trinucleotides were completely unable to support interference, while the remaining 28 fell into either the rapid or attenuated interference categories [13].

The consensus PAM sequences for the E. coli Type I-E system include AAG and ATG, which support rapid interference [13]. Interestingly, PAM variants that support intermediate-rate interference consistently stimulate strong "primed adaptation" - a process where partially matched targets lead to highly efficient acquisition of new spacers from adjacent DNA sequences [13]. This relationship suggests that attenuated interference creates sustained conditions favorable for spacer acquisition, highlighting the functional connection between PAM recognition and adaptive immunity in Type I systems.

Type II Systems

Type II CRISPR-Cas systems utilize a single effector protein (Cas9) for target interference and represent the most widely used systems for genome engineering applications [15]. These systems are further subdivided into II-A, II-B, and II-C subtypes, with Type II-C accounting for nearly half of all known Type II systems [15].

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Type II CRISPR-Cas Systems

| Cas Nuclease | Organism | System Type | PAM Sequence (5'→3') |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | II-A | NGG [3] [14] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | II-A | NNGRRT or NNGRRN [3] [11] |

| Nme1Cas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | II-C | NNNNGATT [3] |

| Nme2Cas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | II-C | N4CC [16] |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | II-C | NNNNRYAC (Y = C/T) [3] [16] |

| StCas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | II-A | NNAGAAW [3] |

| BlatCas9 | Brevibacillus laterosporus | II-C | N4CNAA [16] |

Type II-C Cas9 orthologs display remarkable PAM diversity despite phylogenetic relatedness. A recent study investigating 29 Nme1Cas9 orthologs revealed that 25 were active in human cells and recognized PAMs with variable length and nucleotide preference, including purine-rich, pyrimidine-rich, and mixed PAMs [16]. This diversity highlights the natural expansion of PAM recognition capabilities among closely related Cas9 proteins, providing a rich resource for genome engineering tool development.

The PAM interaction domain (PID) of Cas9 is responsible for recognizing specific PAM sequences [15]. Structural studies have identified key residues (Q981, H1024, T1027, and N1029 in Nme1Cas9) that are crucial for PAM recognition [16]. Variations in these residues across orthologs contribute to their diverse PAM specificities, enabling the recognition of different PAM sequences despite structural conservation [16].

Type V Systems

Type V CRISPR-Cas systems utilize Cas12 family effectors (including Cas12a/Cpf1, Cas12b, and others) and represent another single-protein interference system (Class 2) with distinct PAM recognition patterns and cleavage mechanisms [17] [11].

Table 2: PAM Sequences for Type V CRISPR-Cas Systems

| Cas Nuclease | Organism | PAM Sequence (5'→3') |

|---|---|---|

| AsCas12a (Cpf1) | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV (V = A/C/G) [3] [17] |

| LbCas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV (V = A/C/G) [3] [17] |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN [3] |

| BhCas12b v4 | Bacillus hisashii | ATTN, TTTN, GTTN [3] |

| Cas12f1 | Engineered | NTTR [11] |

| PlmCas12e | Engineered | TTCN [11] |

Unlike Cas9, which requires both a crRNA and tracrRNA for activity, Cas12a utilizes only a single CRISPR RNA (crRNA) without needing tracrRNA [17]. Cas12a recognizes T-rich PAM sequences (TTTV) located upstream of the target sequence and creates staggered DNA cuts with 5' overhangs, in contrast to the blunt ends generated by Cas9 [17]. Cas12a cleaves the target DNA 18-19 bases from the 3' end of the PAM on the PAM-containing strand and 23 bases from the PAM on the opposite strand, resulting in a 5' overhang of 4-5 bases [17].

Engineered Cas12a variants such as Alt-R Cas12a Ultra have expanded PAM recognition capabilities, accepting TTTN sequences (where N is any nucleotide) and showing increased editing efficiency across a range of temperatures [17] [11]. This expanded recognition capability is particularly valuable for targeting AT-rich genomic regions that may be inaccessible to Cas9 systems [17].

Experimental Methods for PAM Identification

Several high-throughput methods have been developed to systematically identify PAM sequences for various CRISPR-Cas systems, each with specific advantages and limitations.

In Vivo PAM Identification Methods

Plasmid Depletion Assays involve transforming a plasmid library containing randomized DNA sequences adjacent to a target protospacer into host cells with an active CRISPR-Cas system [8]. Functional PAM sequences lead to plasmid cleavage and depletion, while non-functional PAMs allow plasmid retention. The relative abundance of PAM variants is determined through next-generation sequencing of plasmid libraries before and after selection [13] [8].

PAM-SCANR (PAM Screen Achieved by NOT-gate Repression) utilizes a catalytically dead Cas variant (dCas9) coupled with a GFP reporter system [8] [16]. When dCas9 binds to a functional PAM, it represses GFP expression. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) separates cells based on GFP levels, followed by sequencing to identify functional PAM motifs [8]. This approach was used to characterize PAM diversity among 29 Nme1Cas9 orthologs, revealing their distinct PAM preferences [16].

In Vitro PAM Identification Methods

In Vitro Cleavage Assays utilize purified Cas effector complexes and DNA libraries containing randomized PAM sequences [8]. Cleaved products are selectively enriched and sequenced, or alternatively, uncleaved targets are sequenced to identify non-functional PAMs [8]. This approach allows for greater control over reaction conditions and enables screening of larger initial libraries but requires purified, active effector complexes [8].

Bioinformatic Approaches involve computational analysis of protospacer sequences from known phage genomes to identify conserved PAM elements through sequence alignment [8]. Tools such as CRISPRFinder and CRISPRTarget facilitate this process, providing a rapid method for PAM prediction, though this approach cannot distinguish between functional PAM variants or account for potential mutations [8].

PAM Engineering and Novel Variants

The natural diversity of PAM sequences has been expanded through protein engineering approaches, resulting in Cas variants with altered PAM specificities that significantly increase the targeting scope of CRISPR technologies.

Engineered Cas9 Variants

Several engineered SpCas9 variants have been developed to recognize alternative PAM sequences:

- xCas9: Recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs with increased fidelity [14]

- SpCas9-NG: Recognizes NG PAMs with improved in vitro activity [14]

- SpG: Recognizes NGN PAMs with increased nuclease activity [14]

- SpRY: Recognizes NRN and NYN PAMs, approaching PAM-less flexibility [14]

These engineered variants substantially expand the targetable genomic space while maintaining efficient editing activity. For example, SpRY's recognition of both purine and pyrimidine PAMs dramatically increases potential target sites compared to wild-type SpCas9 [14].

Engineered Cas12 Variants

Similar engineering efforts have been applied to Cas12 nucleases:

- Alt-R Cas12a Ultra: Recognizes TTTN PAMs in addition to standard TTTV motifs, increasing target range and displaying higher editing efficiency across varied temperatures [17] [11]

- hfCas12Max: An engineered high-fidelity Cas12 variant recognizing TN and/or TNN PAM sequences [3]

These engineered Cas12 variants are particularly valuable for applications in organisms with AT-rich genomes or when working at non-standard temperatures [17].

Chimeric Cas Proteins

Researchers have created chimeric Cas nucleases by swapping PAM-interaction domains between orthologs to generate novel PAM specificities. One such chimeric Cas9 recognizes a simple N4C PAM, representing one of the most relaxed PAM preferences for compact Cas9s to date [16]. This approach leverages natural diversity while maintaining protein stability and function.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAM Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R Cas12a Ultra Nuclease | Engineered Cas12a with expanded PAM recognition | Recognizes TTTN PAMs; high efficiency in mammalian and plant systems [17] |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Reduced off-target editing while maintaining on-target activity | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9, evoCas9 [14] |

| PAM-Flexible Cas9 Variants | Expanded targeting scope with alternative PAM recognition | xCas9 (NG, GAA, GAT), SpCas9-NG (NG), SpG (NGN), SpRY (NRN/NYN) [14] |

| Cas12 Nucleases | Type V CRISPR systems with T-rich PAM recognition | AsCas12a, LbCas12a (TTTV PAM); AacCas12b (TTN PAM) [3] [17] |

| PAM Library Kits | Comprehensive PAM screening with randomized sequences | Plasmid libraries with randomized trinucleotides for depletion assays [13] [8] |

| dCas9 Screening Systems | PAM identification without DNA cleavage | PAM-SCANR using catalytically dead Cas9 with reporter systems [8] |

Advanced Applications and PAM Bypass Strategies

Recent developments in CRISPR diagnostics have led to innovative methods that circumvent PAM restrictions. The PICNIC (PAM-free Identification with CRISPR-based Nucleic Acid Detection) method enables PAM-free detection by separating dsDNA into single strands through a brief high-temperature and high-pH treatment, allowing Cas12 enzymes to detect released ssDNA without PAM requirements [18].

This approach has been successfully applied with multiple Cas12 subtypes (Cas12a, Cas12b, and Cas12i) for PAM-independent detection of clinically important single-nucleotide polymorphisms, including drug-resistant variants of HIV-1 (K103N mutant) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotyping [18]. Such PAM bypass strategies significantly enhance the flexibility and precision of CRISPR-based diagnostics, particularly for targets with limited PAM availability.

PAM sequences represent a fundamental component of CRISPR-Cas systems that directly influences their targeting scope, specificity, and application potential. The natural diversity of PAM recognition across different CRISPR types, combined with engineered variants and innovative bypass strategies, continues to expand the capabilities of genome engineering and molecular diagnostics. Understanding PAM requirements remains essential for selecting appropriate CRISPR systems for specific applications and for developing novel tools with enhanced targeting flexibility. As research progresses, the continued exploration of natural CRISPR diversity and the development of engineered variants promise to further overcome PAM-related limitations, unlocking new possibilities for precise genetic manipulation and detection.

The Mechanistic Role of PAM in Cas9 Binding and DNA Interrogation

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) serves as an essential recognition signal that licenses the CRISPR-Cas9 system for DNA interrogation and cleavage. This technical guide examines the mechanistic basis of PAM-dependent DNA targeting, drawing on structural biology, single-molecule dynamics, and biochemical studies. We detail how PAM recognition initiates directional DNA unwinding, facilitates RNA-DNA hybrid formation, and ultimately triggers Cas9 catalytic activation. The foundational principles outlined herein provide a framework for understanding Cas9 function and engineering novel genome-editing tools with altered PAM specificities.

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR-Cas9 system [3]. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide base [4]. This motif is not part of the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) guide sequence and must be present immediately downstream of the target sequence in the genomic DNA for successful recognition and cleavage [3] [4].

The PAM sequence solves a critical self versus non-self discrimination problem in bacterial adaptive immunity. When bacteria incorporate viral DNA fragments (protospacers) into their own CRISPR arrays, they exclude the PAM sequence [3]. Consequently, the bacterial genome contains spacer sequences without adjacent PAMs, preventing autoimmunity and ensuring that Cas9 only targets foreign DNA containing both the spacer-complementary sequence and the adjacent PAM [3].

Structural Basis of PAM Recognition

Molecular Interactions at the PAM Interface

Structural studies have revealed that PAM recognition occurs primarily through specific interactions between Cas9 and the double-stranded PAM duplex. Crystallographic analysis of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 complexed with sgRNA and target DNA demonstrates that the PAM-containing region forms a base-paired DNA duplex nestled in a positively charged groove between the Topo-homology and C-terminal domains of Cas9 (collectively termed the PAM-interacting domain) [19].

Table 1: Key Cas9 Residues Involved in PAM Recognition and Their Functions

| Protein Residue | Domain | Interaction Partner | Functional Role | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arg1333 | C-terminal | dG2* (non-target strand) | Major groove readout of first G base | Alanine substitution reduces DNA binding and cleavage [19] |

| Arg1335 | C-terminal | dG3* (non-target strand) | Major groove readout of second G base | Alanine substitution reduces DNA binding and cleavage [19] |

| Lys1107 | PAM-interacting | dC-2 (target strand) | Enforces pyrimidine preference at -2 position | Explains weak permissiveness of NAG PAMs [19] |

| Ser1109 | PAM-interacting | +1 phosphate (target strand) | "Phosphate lock" that stabilizes unwound DNA | Contributes to local strand separation [19] |

| Trp476, Trp1126 | - | - | Not in direct PAM contact | May participate in transient recognition intermediates [19] |

The molecular recognition mechanism shows remarkable specificity: the guanine bases of dG2* and dG3* in the non-target strand are read out in the major groove via base-specific hydrogen-bonding interactions with Arg1333 and Arg1335, respectively, provided by a beta-hairpin from the C-terminal domain [19]. This explains why Cas9 requires the 5'-NGG-3' trinucleotide in the non-target strand, but not its complement in the target strand [19].

The Phosphate Lock Mechanism

Beyond base-specific recognition, Cas9 makes critical contacts with the DNA backbone that facilitate downstream events. The "phosphate lock" loop (residues Lys1107-Ser1109) interacts with the phosphodiester group linking dA-1 and dT1 in the target DNA strand (the +1 phosphate) [19]. Non-bridging phosphate oxygen atoms form hydrogen bonds with the backbone amide groups of Glu1108 and Ser1109, and with the side chain of Ser1109 [19]. This interaction rotates the +1 phosphate group and creates a distortion in the target DNA strand that enables the nucleobase of dT1 to base pair with the guide RNA [19].

The phosphate lock mechanism functionally links PAM recognition with local strand separation. Biochemical experiments confirm that alanine substitution of Lys1107 or replacement of the Lys1107-Ser1109 loop with simplified dipeptides yields Cas9 proteins with modestly reduced cleavage activity on perfectly matched DNA but nearly abolished activity on DNA containing mismatches to the guide RNA at positions 1-2 [19].

Figure 1: Sequential Mechanism of PAM-Dependent DNA Interrogation by Cas9

DNA Interrogation Mechanism

Single-Molecule Insights into Target Search

Single-molecule studies using DNA curtain assays have illuminated how Cas9 interrogates DNA to locate specific targets. Cas9:guide RNA complexes employ a three-dimensional (3D) collision mechanism rather than facilitated diffusion (1D sliding or hopping) to locate target sites [20]. This search strategy differs from many other DNA-binding proteins that utilize sliding along DNA contours.

Table 2: Cas9-DNA Binding Characteristics Revealed by Single-Molecule Studies

| Binding State | Lifetime | Salt Sensitivity | Response to Competitors | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo-Cas9 (no guide RNA) | >45 minutes (lower limit) | High | Dissociates with heparin or RNA | Non-specific DNA association |

| Cas9:RNA Non-specific | Biexponential: ~3.3s and ~58s (25mM KCl) | Low | Dissociates with competitors | Probing potential target sites |

| Cas9:RNA Specific | Essentially permanent until urea denaturation | Resists 0.5M NaCl | Resistant to heparin and excess RNA | Stable product binding after cleavage |

The target search efficiency correlates with PAM density throughout the genome. Quantitative analysis reveals that Cas9:RNA binding site distribution positively correlates with PAM distribution (Pearson correlation r = 0.59, P <0.05) [20]. This relationship becomes even stronger (r = 0.84) when using guide RNAs with no complementary target sites within the DNA substrate, indicating that Cas9:RNA complexes specifically probe PAM-rich regions during target search [20].

Directional DNA Unwinding and R-loop Formation

PAM recognition initiates directional unwinding of the target DNA duplex. Following PAM binding, DNA strand separation and RNA-DNA heteroduplex formation begin at the PAM and proceed directionally toward the distal end of the target sequence [20]. This directional mechanism ensures efficient sampling of potential targets while minimizing time spent on non-target sequences.

The structural transition from PAM recognition to DNA cleavage involves significant conformational changes in Cas9. Guide RNA binding induces a dramatic structural rearrangement that shifts Cas9 into an active, DNA-binding configuration [14]. Upon target binding with correct PAM recognition, Cas9 undergoes a second conformational change that positions its nuclease domains (RuvC and HNH) to cleave opposite strands of the target DNA [14].

Experimental Analysis of PAM Function

Structural Biology Approaches

Crystallographic Protocol for Cas9-DNA Complex Analysis

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify catalytically inactive Cas9 (D10A/H840A mutants) to prevent DNA cleavage during crystallization [19].

- Complex Formation: Incubate Cas9 with sgRNA and target DNA containing canonical PAM (e.g., 5'-TGG-3') [19].

- Crystallization: Use vapor diffusion methods with optimized conditions to obtain diffraction-quality crystals.

- Data Collection and Structure Determination: Collect X-ray diffraction data and solve structure using molecular replacement.

This approach revealed the precise molecular contacts between Cas9 and the PAM sequence, showing that the entire PAM-containing region of the target DNA is base-paired, with strand separation occurring only at the first base pair of the target sequence [19].

Biochemical Assays for PAM Requirements

In Vitro Cleavage Assay Protocol

- Substrate Design: Prepare target DNAs with systematic PAM variations (e.g., NGG, NGA, NGC, NGT, NAG) [19] [21].

- Cleavage Reactions: Incubate wild-type or mutant Cas9:RNA complexes with target DNA substrates under defined buffer conditions.

- Product Analysis: Resolve cleavage products by gel electrophoresis and quantify efficiency.

- Binding Measurements: Use gel shift assays or surface plasmon resonance to measure binding affinity for different PAM variants.

Application of this methodology demonstrated that alanine substitution of both Arg1333 and Arg1335 nearly abolished cleavage of linearized plasmid DNA and substantially reduced cleavage of supercoiled circular plasmid DNA and short dsDNA oligonucleotides [19].

Single-Molecule Imaging Techniques

DNA Curtain Assay Protocol for Target Search Visualization

- Substrate Preparation: Anchor λ-DNA (48,502 bp) to supported lipid bilayers in microfluidic chambers [20].

- Protein Labeling: Tag Cas9 with fluorescent quantum dots via C-terminal 3x-FLAG epitope and antibody conjugation [20].

- Image Acquisition: Use total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) to visualize binding events in real-time [20].

- Data Analysis: Track binding locations and lifetimes relative to known PAM distribution across the DNA substrate.

This technique confirmed that Cas9:RNA locates targets exclusively through 3D diffusion and revealed complex dissociation kinetics for non-specific binding events, providing insights into the target search mechanism [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating PAM Recognition

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 D10A/H840A | Catalytically inactive mutant | Structural studies and DNA binding assays | Enables crystallization of intact complexes [19] [20] |

| Single-molecule guide RNA (sgRNA) | 83-nucleotide chimeric RNA | DNA interrogation and cleavage assays | Combines crRNA and tracrRNA functions [19] |

| PAM Variant Library | DNA substrates with systematic PAM mutations | Specificity profiling and interference determination | Identifies permissive vs. non-permissive PAMs [21] |

| Quantum Dot-labeled Cas9 | C-terminal 3x-FLAG tag with antibody-QD conjugation | Single-molecule visualization | Enables real-time tracking of search dynamics [20] |

| Protein2PAM Deep Learning Model | Trained on 45,000+ CRISPR-Cas PAMs | PAM specificity prediction and protein engineering | Enables in silico deep mutational scanning [22] |

Figure 2: Functional Interdependence in Cas9 DNA Interrogation Process

Engineering PAM Specificity

Recent advances in protein engineering have enabled the development of Cas9 variants with altered PAM specificities. Machine learning-based approaches, such as Protein2PAM, leverage vast evolutionary data to predict PAM specificity directly from Cas protein sequences and identify critical residues for PAM recognition [22]. This evolution-informed deep learning model, trained on over 45,000 CRISPR-Cas PAMs, enables computational evolution of Cas proteins with customized PAM recognition [22].

Applied to Nme1Cas9, this approach generated variants with broadened PAM recognition and up to a 50-fold increase in PAM cleavage rates compared to wild-type under in vitro conditions [22] [23]. Such engineering efforts are crucial for expanding the targetable genomic space for therapeutic applications, as the PAM requirement traditionally limited the range of accessible sequences [22] [3].

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif serves as the fundamental licensing signal that initiates the entire DNA interrogation process by Cas9. Through specific protein-DNA contacts, particularly with the non-target strand GG dinucleotide, PAM recognition triggers a cascade of events including DNA bending, directional unwinding, R-loop formation, and ultimately catalytic activation. The mechanistic insights from structural, biochemical, and single-molecule studies not only elucidate the fundamental biology of CRISPR-Cas systems but also provide a robust foundation for engineering next-generation genome editing tools with enhanced specificity and expanded targeting capabilities.

PAM in Practice: Guide RNA Design and Therapeutic Genome Editing

Incorporating PAM Requirements into gRNA Design Rules

The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) represents a fundamental sequence requirement for most CRISPR-Cas systems, serving as the critical first step in target recognition and a primary determinant of targetable genomic space [3] [24]. This short, specific DNA sequence adjacent to the target protospacer functions as a binding signal for Cas effector proteins, enabling them to distinguish between self and non-self DNA—a crucial biological safeguard that prevents autoimmune destruction of the bacterial CRISPR array [3] [24]. From a practical standpoint, the PAM requirement constrains targetable sites within any genome, making its consideration the foundational step in any gRNA design strategy [25] [3]. The PAM sequence varies significantly between different CRISPR-Cas systems and must be empirically determined for each system, particularly when working with endogenous or novel Cas effectors [26] [24]. As CRISPR technologies advance toward therapeutic applications, precisely understanding and incorporating PAM requirements into gRNA design has become increasingly critical for achieving both high editing efficiency and minimal off-target effects [12].

PAM Fundamentals: Location, Sequence, and Conservation Across Cas Enzymes

Key Characteristics and Locations

The PAM is typically a short DNA sequence, usually 2-6 base pairs in length, located directly adjacent to the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR system [3]. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide base, positioned 3-4 nucleotides downstream from the cut site [3]. The location of the PAM relative to the protospacer varies between CRISPR-Cas system types: for Type I and V systems, the PAM is typically located on the 5' end of the protospacer, while for Type II systems, it is found on the 3' end [24]. This location difference has led to confusion in reporting PAM sequences, prompting calls for standardized "guide-centric" orientation where the PAM is located on the strand matching the guide RNA sequence [24].

PAM Diversity Across CRISPR-Cas Systems

Different Cas nucleases recognize distinct PAM sequences, expanding the potential target space available to researchers. The table below summarizes PAM sequences for several commonly used and engineered Cas enzymes.

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Various CRISPR-Cas Nucleases

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| LbCas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| AsCas12a (Cpf1) | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| Cas3 | Various prokaryotes | No PAM requirement |

This diversity enables researchers to select Cas enzymes based on PAM availability at their target locus or to target genomic regions inaccessible to enzymes with more restrictive PAM requirements [3]. Additionally, engineered Cas variants like SpG and SpRY have been developed with altered PAM specificities to further expand targeting capabilities [12].

Practical Integration of PAM Requirements into gRNA Design

Core Design Principles

Effective gRNA design must balance on-target efficiency with minimal off-target activity, with PAM selection being the initial critical decision [25]. The target sequence must be immediately adjacent to a compatible PAM sequence, with the optimal protospacer length for Cas9 being 20 nucleotides preceding the PAM [25]. When designing the gRNA sequence, researchers should not include the PAM sequence itself in the guide RNA, as this follows the natural mechanism bacteria use to avoid self-targeting their own CRISPR arrays [3]. However, specialized applications like homing guide RNAs intentionally include the PAM sequence to enable self-targeting for cellular barcoding and lineage tracing [3].

Design Workflow and Computational Tools

A systematic approach to gRNA design incorporating PAM requirements involves multiple steps, as visualized in the following workflow:

Diagram 1: gRNA Design Workflow Incorporating PAM Requirements

Several computational tools facilitate this design process. The IDT CRISPR guide RNA design tool allows researchers to search for predesigned sgRNA sequences or design custom gRNAs, providing both on-target and off-target scores for each candidate [25]. For novel or endogenous CRISPR-Cas systems, bioinformatic tools like Spacer2PAM can predict functional PAM sequences by analyzing natural spacer sequences from CRISPR arrays and identifying conserved motifs adjacent to protospacer origins [26]. These computational predictions can guide the design of smaller, more focused PAM libraries for experimental validation, particularly valuable for systems in slow-growing or difficult-to-transform organisms [26].

Advanced Design Considerations: Nickase Systems

For applications requiring enhanced specificity, Cas9 nickase systems utilize paired gRNAs to create staggered cuts while reducing off-target effects. The D10A Cas9 mutant (inactivated RuvC domain) cleaves only the target strand, while the H840A mutant (inactivated HNH domain) cleaves only the non-target strand [27]. Optimal design rules for nickase systems include:

- Orientation: Use PAM-out configuration where PAM sequences are on the extremes of the targeted region [27]

- Spacing: For D10A nickase, maintain 37-68 bp between nick sites; for H840A, 51-68 bp separation [27]

- HDR Applications: D10A demonstrates higher HDR efficiency, with insertions placed between nick sites using 40 nt homology arms for small insertions and 100 nt arms for larger inserts [27]

Experimental Methods for PAM Determination and Validation

PAM-readID: A Mammalian Cell-Based Determination Method

Understanding PAM requirements for novel Cas enzymes requires robust experimental methods. PAM-readID (PAM REcognition-profile-determining Achieved by Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides Integration) represents a recent advancement for determining PAM recognition profiles in mammalian cells [12]. This method is particularly valuable as PAM preferences show intrinsic differences between in vitro, bacterial, and mammalian cellular environments due to variations in DNA topology, modifications, and cellular context [12].

The experimental workflow involves:

- Library Construction: A plasmid library containing target sequences flanked by randomized PAM sequences

- Transfection: Co-transfection of the PAM library plasmid, Cas nuclease/sgRNA expression plasmid, and double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODN) into mammalian cells

- Cleavage and Integration: Cas cleavage at functional PAM sites followed by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated integration of dsODN

- Amplification and Sequencing: PCR amplification using a dsODN-specific primer and target-plasmid-specific primer, followed by high-throughput sequencing

- Analysis: Bioinformatic analysis to identify PAM sequences associated with cleavage events [12]

PAM-readID has successfully defined PAM profiles for SaCas9, Nme1Cas9, SpCas9, SpG, SpRY, and AsCas12a in mammalian cells, identifying both canonical and non-canonical PAM sequences with high sensitivity—even with sequence depths as low as 500 reads [12].

Alternative PAM Determination Methods

Several complementary methods exist for PAM determination:

- In Vitro PAM Determination: Utilizes PCR-based enrichment of cleaved products followed by high-throughput sequencing, providing a straightforward biochemical approach [12]

- Plasmid Depletion Assay: A negative selection approach used in bacterial cells where functional PAM sequences are depleted from a library after Cas cleavage [12]

- Fluorescent Reporter Systems: Methods like PAM-DOSE (PAM Definition by Observable Sequence Excision) use fluorescent markers and FACS sorting to identify functional PAMs but are more technically complex [12]

Table 2: Comparison of PAM Determination Methods

| Method | Cellular Context | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAM-readID | Mammalian cells | Simple workflow; no FACS required; works with low sequencing depth | Requires dsODN integration and specialized analysis |

| In Vitro Assay | Cell-free system | Direct biochemical measurement; controlled environment | May not reflect cellular environment |

| Plasmid Depletion | Bacterial cells | Works in prokaryotic context; well-established | Limited to transformable bacteria |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Mammalian cells | Visual readout; enables single-cell analysis | Complex construction; requires FACS equipment |

Research Reagent Solutions for PAM-Focused gRNA Design

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAM and gRNA Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA | Synthetic single-guide RNA molecules (99-100 nt) with modified bases for enhanced stability | Integrated DNA Technologies [25] |

| Cas9 Nickase Variants | Engineered Cas9 proteins (D10A, H840A) for paired nicking applications | Addgene [27] |

| CRISPR gRNA Design Tools | Computational prediction of on-target efficiency and off-target effects | IDT, Synthego [25] [3] |

| Spacer2PAM Software | Computational prediction of PAM sequences from CRISPR array data | Open-source R package [26] |

| PAM Library Plasmids | Vector systems with randomized PAM sequences for empirical determination | Custom synthesis [12] |

| Long ssDNA Donors | Homology-directed repair templates for large insertions (e.g., IDT Megamer) | Integrated DNA Technologies [27] |

The strategic incorporation of PAM requirements into gRNA design rules represents a critical factor in successful CRISPR experimental outcomes. Researchers must consider the PAM as a fundamental constraint that dictates targetability, influences efficiency, and affects specificity. As the CRISPR toolbox expands to include novel Cas enzymes with diverse PAM specificities, and as existing enzymes are engineered to recognize alternative PAM sequences, the principles of careful PAM consideration remain constant. By following systematic design workflows, utilizing appropriate computational tools, and validating predictions with empirical methods like PAM-readID, researchers can maximize editing efficiency while minimizing off-target effects—a crucial consideration as CRISPR technologies advance toward therapeutic applications in drug development and clinical medicine.

PAM Sequences for Common and Novel Cas Nucleases (SpCas9, SaCas9, Cas12a)

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by CRISPR-Cas systems [3]. This sequence is a fundamental requirement for most CRISPR-Cas systems to function, as it enables the Cas nuclease to distinguish between foreign genetic material and the host's own DNA [8] [2]. The PAM sequence is located directly adjacent to the target DNA sequence (the protospacer) and is generally found 3-4 nucleotides downstream from the Cas nuclease cut site [3]. From a biological perspective, the PAM sequence serves as a critical "self" versus "non-self" discrimination mechanism, preventing CRISPR systems from targeting the bacterial genome itself, as the host's CRISPR arrays lack these specific adjacent motifs [3] [8].

The functional role of PAM sequences extends across multiple stages of the CRISPR-Cas immune response. Research has revealed that PAMs are involved in both the acquisition of new spacers (where they may function as a Spacer Acquisition Motif or SAM) and the interference stage (where they may act as a Target Interference Motif or TIM) [21]. While these motifs often overlap, the sequence requirements and stringency may differ between the two processes due to their distinct molecular mechanisms [21]. When designing CRISPR experiments, the genomic locations that can be targeted are fundamentally constrained by the presence and distribution of PAM sequences specific to the chosen Cas nuclease, making PAM recognition a crucial consideration in genome engineering experimental design [3].

PAM Requirements and Recognition Mechanisms

PAM Recognition by Different CRISPR Systems

The location and sequence of PAM motifs vary significantly across different CRISPR-Cas types and subtypes, reflecting the evolutionary diversity of these systems [2]. In Class 1, type I systems, the PAM is typically located adjacent to the 5'-end of the protospacer (PAM-Protospacer), while in Class 2, type II systems, it is found at the 3'-end (Protospacer-PAM) [2]. Interestingly, type V systems (including Cas12a) resemble type I systems in utilizing 5'-PAMs [2]. This variation in PAM positioning corresponds to differences in the molecular architecture and mechanisms of the respective Cas effector complexes.

The structural basis for PAM recognition has been elucidated through crystallographic and cryo-EM studies of various Cas effector complexes [8] [28]. These structures reveal that Cas proteins have evolved specialized PAM-interacting domains that enable specific recognition of the short DNA signature sequences [8]. For example, in Cas12a, the WED II-III, REC1, and a dedicated PAM-interacting (PI) domain collaborate to recognize the PAM sequence [28]. A conserved loop-lysine helix-loop (LKL) region within the PI domain, containing three critical lysine residues, inserts into the PAM duplex to facilitate recognition [28]. This multi-domain quality control mechanism ensures accurate identification of target sequences while distinguishing host from foreign DNA.

PAM Sequences for Common and Novel Cas Nucleases

The PAM requirements for commonly used Cas nucleases are summarized in the table below, which provides a comprehensive reference for researchers selecting appropriate nucleases for specific targeting applications.

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Common and Novel Cas Nucleases

| Cas Nuclease | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | CRISPR Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | II-A [3] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN | II-C [3] |

| LbCas12a | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV | V-A [3] |

| AsCas12a | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV | V-A [3] [11] |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN | V [3] |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | II-C [3] |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC | II-C [3] |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | V-B [3] |

| Cas12f1 | Various | NTTR | V-F [11] |

Note: In PAM sequences, N represents any nucleotide; R represents A or G; V represents A, C, or G; Y represents C or T.

The most commonly used Cas nuclease, SpCas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, recognizes a simple NGG PAM sequence, where "N" can be any nucleotide base followed by two guanines [3] [11]. This relatively simple PAM occurs approximately every 8-12 base pairs in random DNA sequences, providing substantial targeting flexibility. In contrast, SaCas9 from Staphylococcus aureus recognizes the more complex NNGRRT (or NNGRRN) PAM, which offers a compact nuclease size advantageous for viral packaging but with more restricted targeting options [3].

The Cas12a family (including LbCas12a and AsCas12a) recognizes TTTV PAM sequences, where "V" represents A, C, or G (but not T) [3] [11]. This T-rich PAM makes Cas12a particularly suitable for targeting AT-rich genomic regions where Cas9 might have limited options [29]. Engineered variants such as Alt-R Cas12a Ultra have further expanded PAM recognition to TTTN, increasing the target range [11]. Continued discovery and engineering of novel Cas nucleases have yielded variants with increasingly diverse PAM specificities, significantly expanding the CRISPR targeting landscape.

Table 2: Key Characteristics and Applications of Major Cas Nuclease Families

| Nuclease Family | Key Characteristics | Preferred Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | • Blunt-ended DSBs• Requires tracrRNA• NGG PAM (SpCas9)• High activity in diverse systems | • Gene knockouts• Large fragment deletions• High-efficiency editing |

| Cas12a | • Staggered DSBs with overhangs• Self-processes crRNA• TTTV PAM• AT-rich region targeting | • Multiplexed genome editing• Gene insertions (with overhangs)• AT-rich genomic regions |

Experimental Determination of PAM Sequences

Methodologies for PAM Identification

Several experimental approaches have been developed to identify and characterize PAM sequences for both natural and engineered CRISPR-Cas systems. These methods range from in silico bioinformatic analyses to high-throughput functional screens, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Bioinformatic identification represents the initial approach for PAM discovery, involving alignments of protospacer sequences adjacent to spacers acquired in CRISPR arrays to identify conserved motifs [8]. Tools such as CRISPRFinder and CRISPRTarget facilitate this process by extracting spacer sequences and identifying potential target sequences in genetic elements [8]. While this method is rapid and accessible, it relies on the availability of sequenced phage genomes and cannot distinguish between SAM and TIM motifs or identify non-functional PAM variants [8].

Plasmid depletion assays provide an experimental approach for PAM identification. In this method, a randomized DNA library is inserted adjacent to a target sequence within a plasmid, which is then transformed into a host with an active CRISPR-Cas system [8]. Plasmids are retained only if they contain "inactive" PAM sequences that are not recognized by the Cas nuclease, allowing for identification of functional PAMs through sequencing of the surviving plasmid population [8]. This approach requires extensive library coverage to comprehensively identify functional PAM elements through their depletion from the population.

More recently, high-throughput in vivo methods such as PAM-SCANR (PAM Screen Achieved by NOT-gate Repression) have been developed for comprehensive PAM characterization [8]. This approach utilizes a catalytically dead Cas variant (dCas9) coupled to a transcriptional repression system. When dCas9 binds to a functional PAM, expression of a reporter gene (such as GFP) is diminished. Subsequent fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), plasmid purification, and sequencing identifies all functional PAM motifs based on their repression efficiency [8].

In vitro cleavage assays represent another powerful approach for PAM identification. These methods involve incubating purified Cas effector complexes with DNA libraries containing randomized PAM sequences, followed by sequencing of either the enriched cleavage products (positive screening) or the remaining uncleaved targets (negative screening) [8]. These approaches benefit from larger initial library sizes and better control over reaction conditions but require purified, stable effector complexes that maintain in vivo activity [8].

Visualization of PAM Identification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key methodological approaches for experimental PAM identification:

PAM Identification Methodologies and Characteristics

Comparative Analysis of Cas9 and Cas12a Editing Profiles

Functional Differences and Practical Implications

While both Cas9 and Cas12a create double-strand breaks in DNA, their molecular mechanisms and resulting editing outcomes differ significantly, influencing their suitability for various applications. Cas9 generates blunt-ended cuts typically 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence, while Cas12a creates staggered cuts with 4-5 nucleotide overhangs (often described as "sticky ends") [29]. These structural differences in cleavage products can influence DNA repair pathway preferences and the efficiency of specific gene editing applications, particularly for precise gene insertions [29].

The crRNA biogenesis and guide RNA requirements also differ substantially between these systems. Cas9 requires both a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), often combined into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) of approximately 100 nucleotides [29] [28]. In contrast, Cas12a processes its own pre-crRNA into mature crRNAs without requiring a tracrRNA, making it a unique effector protein with both endoribonuclease and endonuclease activities [28]. This self-processing capability enables simpler multiplexing strategies using CRISPR arrays for targeting multiple genomic sites simultaneously [29].

Recent comparative studies in tomato cells provide empirical evidence of these functional differences. Research demonstrated that LbCas12a, while showing similar overall editing efficiency to SpCas9, induced more and larger deletions than Cas9, which can be advantageous for specific genome editing applications requiring substantial gene disruptions [29]. In studies conducted in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Cas9 and Cas12a ribonucleoprotein complexes co-delivered with ssODN repair templates achieved comparable total editing levels (20-30%), though Cas12a demonstrated slightly higher precision editing [30].

Off-Target Specificity Considerations

The specificity of CRISPR nucleases is a critical consideration for therapeutic applications. Early evidence suggested that Cas12a might have higher intrinsic specificity than Cas9, potentially due to its more stringent seed sequence requirements [29]. However, comprehensive studies in tomato cells revealed that Cas12a can still exhibit off-target activity, with 10 out of 57 investigated off-target sites showing editing, typically with one or two mismatches distal from the PAM sequence [29]. This underscores the importance of careful guide RNA design and off-target prediction for both nuclease families.

Engineered high-fidelity variants have been developed for both Cas9 and Cas12a to address off-target concerns. For example, the Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 nuclease dramatically reduces off-target editing while maintaining robust on-target activity [11]. Similarly, engineered Cas12a variants like hfCas12Max offer improved specificity profiles [3]. These enhanced specificity variants are particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where off-target effects could have serious consequences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR PAM Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Vectors | Delivery of Cas nuclease coding sequence | Human-codon optimized SpCas9, LbCas12a; with nuclear localization signals [29] |

| Guide RNA Cloning Systems | Efficient assembly of crRNA expression cassettes | Golden Gate-based systems (e.g., MoClo toolkit) for modular crRNA assembly [29] |

| PAM Library Kits | Randomized DNA libraries for PAM characterization | Plasmid libraries with degenerate nucleotides at PAM positions [8] |

| Cas Variant Libraries | Engineered nucleases with altered PAM specificities | SpCas9 variants (xCas9, SpCas9-NG), Cas12a Ultra [3] [11] |

| Off-Target Prediction Tools | In silico identification of potential off-target sites | CasOFF-Finder, CRISPOR with customized parameters [29] |

| Amplicon Sequencing Kits | High-throughput analysis of editing outcomes | CleanPlex technology for targeted sequencing [3] [29] |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for successful investigation of PAM sequences and CRISPR nuclease functionality. The toolkit includes both standard molecular biology reagents and specialized tools designed specifically for CRISPR applications. For PAM characterization studies, randomized PAM libraries serve as essential resources for comprehensive profiling of nuclease specificity [8]. These libraries typically contain fully degenerate nucleotides at the PAM position, enabling unbiased assessment of sequence requirements.

For comparative studies of nuclease activity and specificity, validated reference gRNAs and standardized reporter systems provide essential controls. The development of easy-to-use cloning systems, such as Golden Gate-based assembly for crRNA expression, significantly streamlines experimental workflows [29]. Additionally, high-quality purified Cas proteins are essential for both in vitro cleavage assays and the formation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for delivery in certain cell types [30] [8].

Advanced sequencing methodologies represent another critical component of the PAM researcher's toolkit. High-throughput amplicon sequencing enables comprehensive characterization of editing outcomes across multiple target sites simultaneously [29]. When coupled with automated analysis pipelines, this approach provides robust quantitative data on editing efficiency, mutation patterns, and off-target effects—all essential parameters for evaluating PAM-dependent nuclease performance.

The study of PAM sequences represents a fundamental aspect of CRISPR biology with direct implications for genome engineering applications. The continuing diversification of available Cas nucleases with distinct PAM specificities has dramatically expanded the targeting range of CRISPR technologies, while engineered variants with altered PAM recognition further increase targeting flexibility [3] [11]. These advances are particularly valuable for therapeutic applications that require precise targeting of specific genomic loci without flexibility in sequence selection.

Future directions in PAM research will likely focus on several key areas. First, the continued discovery and characterization of novel Cas nucleases from diverse microbial sources will further expand the PAM repertoire [3] [8]. Second, ongoing protein engineering efforts using methods such as directed evolution will produce Cas variants with improved specificity, altered PAM recognition, and enhanced editing efficiency [3] [11]. Finally, structural biology approaches will provide increasingly detailed understanding of PAM recognition mechanisms, informing rational design of next-generation genome editing tools [8] [28].