The Echo of the Big Bang: How Static Rewrote Cosmic History

The accidental discovery that confirmed our universe's explosive origin

The Static That Changed Everything

Imagine two radio astronomers, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, staring at their massive antenna in frustration. For months, they had been plagued by a persistent, faint static that contaminated their measurements. They scrubbed away pigeon droppings, checked every connection, and eliminated every possible source of interference, yet the mysterious noise remained—a faint hiss that seemed to come from everywhere at once. What they didn't yet realize was that they had stumbled upon the oldest signal in the universe: the fading echo of the cosmic birth we now call the Big Bang 9 .

Scientific Discovery

How curiosity and accident intersect to reveal profound truths about our universe.

Theoretical Brilliance

Decades of mathematical work that predicted what experimentalists would later find.

Meticulous Experimentation

The painstaking process of eliminating all possible explanations for unexpected results.

The Theoretical Groundwork: Setting the Stage for a Revolution

Before any experimental evidence emerged, visionary scientists laid the theoretical foundation for the Big Bang theory through mathematical calculations and bold thinking.

An Expanding Universe

In the 1920s, astronomer Edwin Hubble made a revolutionary observation: nearly all galaxies are speeding away from us, and the farther away they are, the faster they're receding. This established Hubble's Law of Cosmic Expansion, which states that a galaxy's recessional velocity equals its distance multiplied by a constant (H) 9 . This relationship pointed toward a startling conclusion—our universe is not static but rapidly expanding.

The Primeval Atom

Building on Hubble's observations, Georges Lemaitre, a Belgian physicist and priest, proposed in 1927 that the universe began from a "primeval atom" or "cosmic egg" that exploded, marking the beginning of space and time. This radical idea initially met with skepticism, even from Albert Einstein, but gained credibility as it provided the most natural explanation for Hubble's expanding universe 9 .

The Cosmic Timeline

1920s

Edwin Hubble discovers the expansion of the universe through observations of distant galaxies.

1927

Georges Lemaitre proposes the "primeval atom" theory, suggesting an explosive beginning to the universe.

1940s

George Gamow, Ralph Alpher, and Robert Herman predict the existence of cosmic background radiation from a hot Big Bang.

1964

Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson accidentally detect the cosmic microwave background radiation.

The Accidental Discovery: Penzias and Wilson's Pesky Noise

The story of how we found concrete evidence for the Big Bang beautifully illustrates how the scientific method often works in practice—through careful observation, hypothesis testing, and sometimes, serendipitous discoveries 6 .

The Holmdel Horn Antenna

In 1964, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were using a massive, ultrasensitive horn antenna in Holmdel, New Jersey, originally built for satellite communication experiments. They aimed to study radio waves from our galaxy but encountered a persistent problem: a uniform microwave static that remained constant regardless of where or when they pointed their antenna. This noise corresponded to a temperature of approximately 3.5 Kelvin (later refined to 2.7 Kelvin or -455°F/-270°C) 9 .

The Holmdel Horn Antenna used by Penzias and Wilson to discover the CMB. Credit: NASA

Eliminating All Possibilities

True to the principles of the scientific method, Penzias and Wilson systematically investigated and eliminated every potential source of this anomaly . Their investigation included:

- Checking equipment connections for technical malfunctions

- Removing pigeon droppings from the antenna

- Testing for terrestrial and solar interference

- Mapping the Milky Way to rule out galactic sources

"We thought it might be due to a variety of causes, from the mundane to the exotic. We even considered the possibility that it was due to the warm bodies of pigeons that had taken up residence in the antenna."

Cosmic Background Radiation: The Universe's Baby Picture

A Theoretical Prediction Confirmed

Unbeknownst to Penzias and Wilson, a team at Princeton University led by Robert Dicke had been actively searching for precisely what they had found. Dicke and his colleagues had independently revived the Big Bang theory and predicted that if the universe began in a hot, dense state, it should have left behind a cool remnant glow filling all space—cosmic background radiation 9 .

When Penzias and Wilson learned of this work, they realized they had stumbled upon this predicted cosmic microwave background (CMB). The two groups published companion papers in 1965—Penzias and Wilson describing their observation, and Dicke's team explaining its cosmological significance.

What the Cosmic Whisper Tells Us

The cosmic microwave background radiation represents the oldest light we can observe, emitted when the universe cooled enough for atoms to form and photons to travel freely, about 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Before this time, the universe was so hot and dense that it was opaque; the CMB gives us a direct snapshot of this pivotal moment 9 .

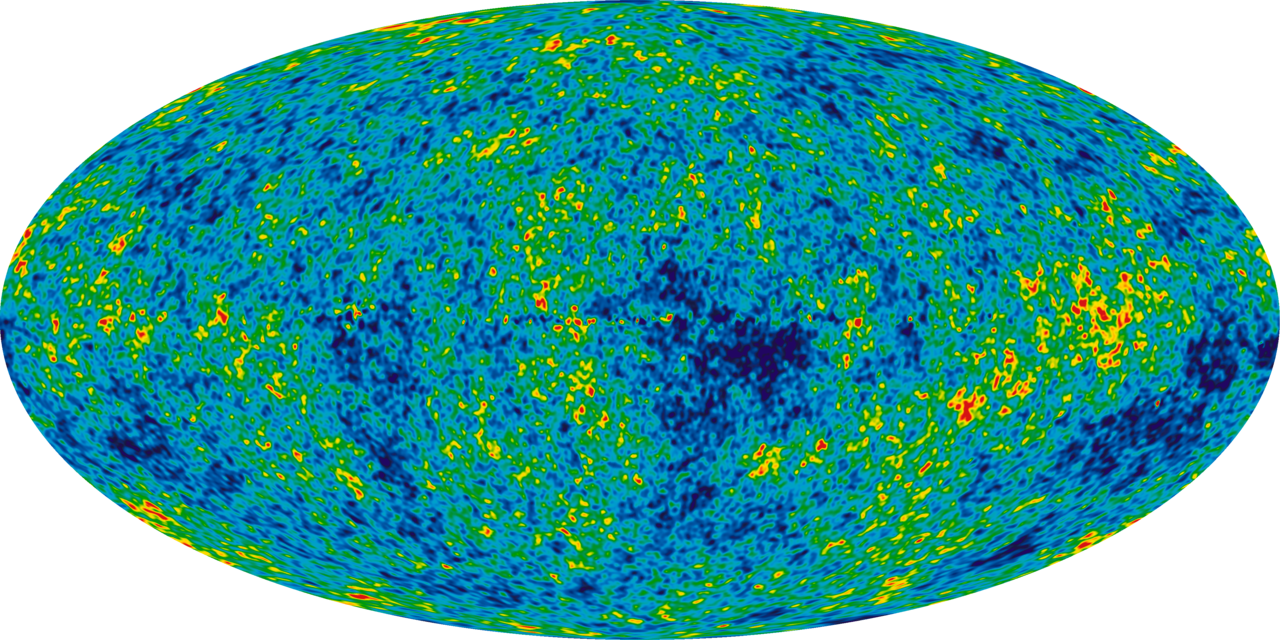

Full-sky map of the cosmic microwave background from the Planck satellite. Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration

Key Properties of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation

| Property | Measurement | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 2.725 Kelvin (-270.425°C) | Confirms cooling prediction from hot Big Bang |

| Wavelength | Microwave region (1.9mm to 10mm) | Corresponds to blackbody radiation of 2.725K |

| Uniformity | Variations of ~1/100,000 degree | Seeds for future galaxy formation |

| Age | ~13.8 billion years | Oldest direct observable light in the universe |

The Universe's Composition Revealed by CMB

Tiny fluctuations in the CMB provide clues about the universe's composition, including the amount of ordinary matter, dark matter, and dark energy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Instruments of Cosmic Discovery

Behind every major astronomical discovery lies an array of specialized instruments and technologies that enable researchers to detect the faint signals from across the cosmos.

Essential Research Tools for Cosmic Discovery

| Tool/Instrument | Function | Example in CMB Research |

|---|---|---|

| Radio Telescopes | Detect radio waves and microwaves from space | Holmdel Horn Antenna used by Penzias and Wilson |

| Cryogenic Systems | Cool detectors to reduce thermal noise | Liquid helium-cooled amplifiers in modern CMB studies |

| Spectral Analyzers | Measure intensity at different wavelengths | Confirm blackbody spectrum of CMB |

| Calibration Sources | Provide reference signals for accuracy | Known temperature loads for instrument calibration |

| Interference Mitigation | Identify and remove contaminating signals | Penzias and Wilson's systematic elimination of interference |

Evolution of CMB Measurement Precision

| Experiment | Year | Key Achievement | Temperature Precision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penzias & Wilson | 1965 | Discovery of CMB | ~3.5 Kelvin (±~0.5K) |

| COBE Satellite | 1990 | Perfect blackbody spectrum confirmed | 2.725 Kelvin (±~0.001K) |

| WMAP Satellite | 2003 | Detailed fluctuation map | 2.725 Kelvin (±~0.0001K) |

| Planck Satellite | 2013 | Highest precision all-sky map | 2.7255 Kelvin (±~0.00001K) |

Timeline of CMB Measurement Precision

Conclusion: Rewriting Our Cosmic Story

The discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation represents a triumph of the scientific process—where theoretical prediction and accidental observation converged to illuminate one of humanity's most profound questions: where did we come from?

Penzias and Wilson's persistent investigation of that frustrating static noise, combined with the theoretical framework developed by scientists like Lemaitre, Dicke, and others, provided the crucial evidence that brought the Big Bang theory to life 9 .

Continuing the Journey

This story continues to evolve as newer technologies like the James Webb Space Telescope peer even further back in time, uncovering earlier chapters of our cosmic history.

A Tangible Connection

What makes this discovery particularly compelling is that each of us carries a tangible connection to it—approximately 1% of the static seen on untuned analog television screens is literally the afterglow of the Big Bang 9 .

This remarkable fact means we can witness the universe's birth with simple technology, a testament to how the echoes of cosmic dawn permeate our everyday world.

"It doesn't matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn't matter how smart you are. If it doesn't agree with experiment, it's wrong."

The journey to understand our universe's beginnings illustrates how science transforms mystery into understanding through a combination of human curiosity, theoretical brilliance, methodological rigor, and sometimes, the willingness to recognize significance in the unexpected. The history that brought the Big Bang to life continues to inspire new generations of scientists to listen carefully to the whispers of the cosmos, reminding us that the universe always has more stories to tell those willing to hear them.